Original Article

doi 10.15171/ijep.2017.28

The Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites and

Associated Risk Factors Among Students of Jahrom

University of Medical Sciences

Hassan Rezanezhad1*, Mohammad Reza Shokouh2, Enayatollah Shadmand3, Nooshin Mohammadinezhad2,

Zahra Mokhtarian2, Arash Fallahi2, Hadi Rezaei Yazdi4, Abbas Ahmadi Vasmehjani4, Belal Armand3

1Department of Parasitology, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

2Student Research Committee, School of Medicine, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran 3Department of Parasitology, School of Medicine, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran 4Department of Immunology and Microbiology, School of Medicine, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences,

Jahrom, Iran

Int J Enteric Pathog. 2017 November;5(4):121-126

http://enterpathog.abzums.ac.irCopyright © 2017 The Author(s); Published by Alborz University of Medical Sciences. This is an open-access article distributed under the

Background

Intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) have been often

described as a significant public health and socioeconomic

problem in developing countries such as Iran though it

is globally pandemic.

1-3For this reason, always national

programs for fighting against the IPIs have been

important. Such programs help to find endemic level

of various intestinal parasites and might help to clarify

whether widespread or focal measures are needed for

control of the parasites. These infections affect many

individuals such as school children, young students

and infants.

4IPIs lead to symptomatic illness or states

of persistent diarrhea and problems with nourishment

and mental growth,

5,6of course, these parasites rarely

cause death. Lack of sanitary facilities, lack of access to

healthy water and poor hygiene, low socioeconomic

status, malnutrition, marginalization, high population

density, illiteracy and other factors give rise to parasitic

infections.

7,8These conditions threaten the population of

the country and the individuals that are more prone to

intestinal parasites. It also imposes an economic burden

on the community. As a result, the infection rate of these

parasites could show the socioeconomic status. Moreover,

the poor people of developing countries experience

Keywords: Prevalence, Intestinal parasites, Students, Jahrom

Abstract

Background: F: Parasitic infections, especially those caused by intestinal agents could affect social and personal hygiene and health; and to avoid the spread of pollution, monitoring the infectious sources is critical.

Objective: The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of intestinal parasites and identify factors associated with intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) among students of Jahrom University of Medical Sciences during 2013-2014.

Materials and Methods: This study was carried out between September 2013 and February 2014. A total of 1293 stool samples were taken from 431 students and were examined by direct wet mounting and formalin-ether methods. A questionnaire for common risk factors was completed for each individual.

Results: Overall, the prevalence of IPIs was estimated to be 125 (29%) that was caused by both pathogenic and pathogenic intestinal parasites. Various species of pathogenic and non-pathogenic protozoa were detected: Entamoeba coli was the most common parasite (9.04%) followed by Blastocystis hominis (8.12%), and Giardia lamblia (4.64%). In the current study, 3.2% of students were infected with multiple parasites. A significant association was observed between the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and the type of accommodation (odds ratio [OR] =1. 5; 95% CI: 1.1; 1.9), parents’ educational level (OR=1. 5; 95% CI: 1.1; 1.9) and gender (OR=1. 5; 95% CI: 1.1; 1.9). No association was detected between the prevalence of infection and age, but a slightly positive prevalence was observed with aging (P=0.66). Conclusion: The data showed that intestinal parasites were slightly more prevalent than expected; that might be due to the interior sources of infection in college, such as carrier students. Hence, performing periodic stool screening of students is a necessity to promote the hygiene among the students.

*Corresponding Author:

Hassan Rezanezhad, Address: Motahhari Street, Department of Parasitology, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran. Tel: +98- 9173086197; Email: rezasiv@gmail.com

Received May 23, 2017; Revised August 20, 2017; Accepted September 3, 2017 Published Online September 23,

2017

International Journal of

Enteric

Pathogens

an infection cycle where malnutrition and repeated

infections lead to excess morbidity that can continue for

several generations.

9People of all ages may be affected

by the prevalence of parasitic infections; therefore, these

infections are not specific to special periods. Interestingly,

transmission possibilities of intestinal parasites increase

in areas with high population density, such as garrisons

and schools. Multiple intestinal parasites cause gastric

symptoms. For instance,

Giardia intestinalis

, the former

Giardia lamblia

, is considered as the most prevalent

protozoan parasite across the world which has affected

almost 200 000 000 people currently.

10,11Another usual

enteric protozoan is

Blastocystis hominis

whose parasitic

traits are still controversial.

7It is believed that over

2 000 000 000 people (nearly one-third of the human

population) are infected with intestinal parasites.

12,13Although, the mortality associated with IPIs is low, the

global number of related deaths is considerable, because

of the extent of the complications.

14Objectives

Consequently, determining the prevalence of the IPIs in

crowded populations, such as university students that are

in potential conditions for the transmission of infection to

each other is critical. Given that there is no information

on the prevalence of the intestinal parasites among the

students of universities in the south of Iran, this study

aimed to determine the prevalence and risk factors of

infection among students of Jahrom University of Medical

Sciences.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

This cross-sectional, population-based survey was

conducted from September 2013 to February 2014. The

study population consisted of 431 students of Jahrom

University of Medical Sciences, an institute in the southern

part of Iran. Simple random sampling method was used

to select the students. We randomly selected 431 male

and female students. After getting official permission

from the university administration, consent forms were

given to all the study students. Then, a questionnaire

based on sociodemographic data (sex, age, education and

socioeconomic level of parents, field of education, and

living place) was designed. After interviewing, 3 stool

samples were collected from each student in alternate

days.

Parasitological Examination

The samples were immediately transported to a

diagnostic laboratory. Then, the samples were examined

for gastrointestinal parasites. Initially, the slides were

prepared directly from each sample based on the wet

mount method using saline as well as iodine, and slides

were microscopically examined. Furthermore, all of the

samples were examined using the formol-ether method.

Briefly, 5 g of each sample was diluted in 7 mL of 5%

formaline and 3 mL ether, followed by centrifugation for

10 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were done using SPSS for windows version

16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical difference for

each independent variable was identified using the

chi-square or student’s

t

test. The variables (risk factors)

and the prevalence of parasitic infection were compared

using logistic regression analysis with an odds ratio and a

confidence interval of 95%. A

P

value less than 0.05 were

regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

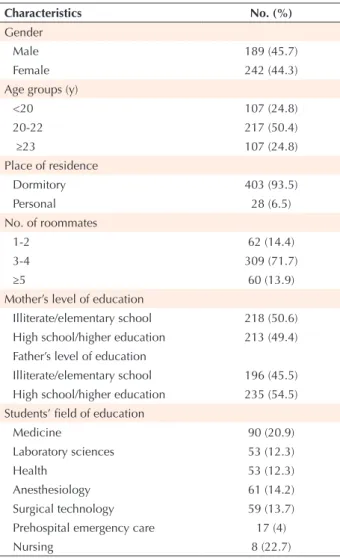

Demographic and socioeconomic data are shown in

Table 1. A total of 1293 stool specimens were examined

from 431 students in college (3 stool samples from each

student in alternate days). The age range was 19–24

years for all students and the mean age was 21.62 ± 2.34

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Project at Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Southern Iran, 2013- 2014Characteristics No. (%)

Gender

Male 189 (45.7)

Female 242 (44.3)

Age groups (y)

<20 107 (24.8)

20-22 217 (50.4)

≥23 107 (24.8)

Place of residence

Dormitory 403 (93.5)

Personal 28 (6.5)

No. of roommates

1-2 62 (14.4)

3-4 309 (71.7)

≥5 60 (13.9)

Mother’s level of education

Illiterate/elementary school 218 (50.6) High school/higher education 213 (49.4) Father’s level of education

Illiterate/elementary school 196 (45.5) High school/higher education 235 (54.5) Students’ field of education

Medicine 90 (20.9)

Laboratory sciences 53 (12.3)

Health 53 (12.3)

Anesthesiology 61 (14.2)

Surgical technology 59 (13.7)

Prehospital emergency care 17 (4)

years. The students were classified based on age, and the

results showed that the distribution was 107 for students

aged <20 years (24.8%), 217 for those aged 20–22 years

(50.4%), and 107 for those aged ≥23 years (24.8%).

Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections

Our findings showed a 29% gastrointestinal parasitic

infection among 431 students. Overall, the prevalence

of infection with only 1 parasite species was 22.03%, the

prevalence of infection with 2 parasites was 2.73%, and the

prevalence of infection with 3 parasite species was 0.46%.

In general, 4 distinct intestinal parasite species were

observed. As it is shown in Table 2, the most common

protozoan species were

Entamoeba coli

(9.04% single,

and 1.8% double infection),

G. lamblia

(4.64% single,

and 1.99% double infection),

B. hominis

(8.12% single,

and 1.11% double infection), and

Enterobius vermicularis

(0.23% single, and 0.46% double infection). Moreover,

triple infection with

B. hominis

,

E. coli

and

G. lamblia

was

0.46%.

Probable Relationship of Independent Variables With

Intestinal Parasitic Infections

As it is declared in Table 3, there were several factors related

to intestinal parasitism including parents’ educational

level, place of residence, gender, and other risk factors.

The prevalence of intestinal parasitism in individuals

living in the dormitory was significantly higher than that

in students living in a personal house (odds ratio [OR] =

1.6; 95% CI: 1.8; 2.6,

P

= 0.01). The prevalence of intestinal

infections in individuals, whose fathers had elementary

level of education, was higher than that in students, whose

fathers had higher educational level, and this prevalence

was statically significant (OR

= 0.5; 95% CI: 0.3; 1.1,

P

= 0.02). Moreover, the rate of intestinal infections in

males was significantly higher than that in females (OR =

1.5; 95% CI: 1.1; 2.1,

P

= 0.01).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the overall rate of IPIs and

the risk factors associated with IPIs among a number

of students of Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, a

medical institute in the southern part of Fars province,

Iran. The prevalence of intestinal parasites was estimated

to be 29%, from which the prevalence of helminth and

protozoan infections were 0.7% and 28.3%, respectively.

Various studies have consistently demonstrated the

widespread distribution of intestinal parasites in Iran

15-19and other countries among different populations,

20,21varying among different races and communities.

Differences in the rate of infection in various studies

could be due to the differences in target populations

and the years in which these surveys were performed.

Comparing our findings with those recently reported

for other populations of Iran, a slightly similar rate of IPI

was revealed. Based on data collected in studies carried

out in different parts of Iran, a 0%–5.8% prevalence of

intestinal helminth parasite infections

15,22,23was reported

that indicated contradictory result with the findings of the

present experiment on students (0.7%), which was lower

than other studies on students in other institutes of Iran

24and other countries.

25However, the current study was

of further importance in comparison with other similar

studies, because students of Jahrom University of Medical

Sciences were studying in interrelated fields with direct

correlations with universal health and this provided

them with higher awareness compared to other groups;

therefore, usual monitoring was found to be more critical.

When there are multiple intestinal infections such

as common IPIs (e.g. infections with

B. hominis

and

G.

lamblia

), we can hypothesize the fact that many species of

protozoa have probably the same route of transmission.

For example, human can be infected with

G. lamblia

by

water and possibly food, and like majority of prevalent

parasites, person-to-person transmission is believed to be

the primary mechanism of infection distribution in the

community of students. Moreover, due to poor personal

hygiene, some students may inadvertently be infected

through food sources.

26On the other hand, the relatively

high prevalence in these individuals could be explained

by poor sanitary conditions, contaminated water supplies,

and high density that in a recent study may be explained as

the result of low awareness among the students regarding

personal hygienic behaviors.

Our results also showed that gender of the students,

living area and parents’ level of education were significantly

correlated with IPI. In our study, the prevalence was

slightly higher in males (34.9%) than in females (24.4%),

Table 2. Prevalence of Single Parasitism and Polyparasitism Among431 Participants in the Project at Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Southern Iran, 2013-2014

Intestinal Parasites Species Prevalence (%) Single Parasitism

Protozoa Entamoeba coli 9.04

Blastocystis hominis 8.12

Giardia lamblia 4.64

Subtotal protozoa (21.21.80%)

Helminths Enterobius vermicularis 0.23

Subtotal helminths 0.23

Polyparasitism

Double B. hominis + E. coli 0.41

E. coli + G. lamblia 1.16

B. hominis + G. lamblia 0.7

G. lamblia+ E. Vermicularis 0.23

E. coli + E. Vermicularis 0.23

Triple B. hominis + E.coli + G.lamblia 0.46 Subtotal mixed

that was statistically a significant difference (

P

= 0.01).

Several studies have reported a higher prevalence of

infection in males than females,

17,19,27whereas other

studies have indicated the opposite findings.

15,18,28In

the present study, infection was more common in the

20-22-year-old age group and was lower in the

20-year-old age group, but these data were not significant.

Interestingly, age is an important risk factor for IPIs; our

finding was similar to that reported in some previous

surveys

24,29and contradictory to some other reports.

9,15,16These differences could be explained by considering the

developed sanitary conditions and behaviors among

students, who were acquainted with proper hygienic

practices in their living places.

Several other risk factors were significantly associated

with IPIs. It was stated that parents’ level of education

was positively associated with the prevalence of pediatric

infection, which the present report confirmed it (

P

=0.02).

However, some studies reported a negative association

in this regard.

30A higher infection rate was observed

among the individuals whose fathers had only elementary

educational level; that was in agreement with the findings

of previous studies.

31-33This indicated that the level of

awareness of parents is directly intertwined with raising

the healthy students that were educated with educational

intervention as an effective means in reducing parasitic

prevalence.

The higher infection rate reported among students

living in dormitory showed a statistically significant

relationship, compared to those living in personal houses

and rental properties (

P

= 0.01). This finding was not in

line with that reported in previous surveys.

24,34This study

Table 3. Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Intestinal Parasitic Infection Among Participants in the Project at Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Southern Iran, 2013-2014

Demographic

& Baseline Characteristics

Parasitic Positive No. (%)

Parasitic Negative

No. (%) OR 95% CI P Value

Gender 0.01

Male 66 (34.9) 183 (65.1)

Female 59 (24.4) 123 (75.6) 1.5 1.1; 2.1

Age groups (y) 0.66

<20 28 (26.2) 79 (73.8)

20-22 63 (29) 154 (71) 0.4 0.1; 0.9

≥23 34 (31.8) 73 (68.2) 0.9 1.3; 2.4

Living regions 0.01

Dormitory 111 (27.5) 292 (72.5)

Personal 14 (50) 14 (50) 1.6 1.8; 2.6

No of roommates 0.68

1-2 19 (30.6) 43 (69.4)

3-4 92 (29.1) 217 (70.2) 0.6 0.7; 1.6

≥5 14 (23.3) 46 (76.7) 1.3 1.9; 2.7

Mother’s level of education 0.09

Illiterate 22 (44.9) 27 (55.1)

Elementary school 27 (26.5) 75 (73.5) 1.7 0.9; 1.4

Tertiary school 20 (29.9) 47 (70.1) 2.2 1.7; 2.1

High school 34 (26) 97 (74) 3.1 2.4; 2.9

Academic 22 (26.8) 60 (73.2) 4.5 3.1; 4.1

Father’s level of education 0.02

Illiterate 20 (38.5) 32 (61.5)

Elementary school 34 (39.5) 52 (60.5) 0.5 0.3; 1.1

Tertiary school 12 (20.7) 46 (79.3) 1.4 1.2; 2.1

High school 27 (22.9) 91 (77.1) 2.7 2.9; 4.1

Academic 32 (27.4) 85 (72.6) 3.6 4.5; 5.8

Students’ field of education 0.39

Medicine 35 (38.9) 55 (61.1)

Laboratory sciences 13 (24.5) 40 (75.5) 1.12 0.87; 1.45

Health 13 (24.5) 40 (75.5) 2.4 2.1; 3.1

Anesthesiology 13 (21.3) 48 (78.7) 3.5 3.6; 4.1

Surgical technology 17 (28.8) 42 (71.2) 4.6 4.5; 5.2

Prehospital emergency 9 (52.9) 8 (47.1) 5.4 5.7; 6.5

also indicated that the high population density increased

the possibility of IPIs. However, our observation did

not suggest a statistically significant relationship

between parasitic infection and either the students’ field

of education (

P

= 0.39) or mothers’ educational level

(

P

= 0.09). Furthermore, the present study showed low

rates of helminths and relatively high rates of potentially

pathogenic protozoan infections, such as

G. lamblia

among students.

Conclusion

As a matter of fact, pathogenic IPIs among students of

medical universities should be frequently monitored

because of their direct relationship to the health of the

community; however, there has been little investigations

done on this group. Therefore, it is suggested that these

students take a set of personal hygienic programs and

behaviors. And in doing so, there exists a need to promote

the mass scale health conditions to raise awareness about

health and hygiene. However, further prospective studies

should be conducted before coming to any conclusion.

Authors’ ContributionsConcept studies and design: HR; Sample collection, administrative, technical, and material support: MRS, ES, NM, ZM, AF, BA; Analysis and interpretation of data: HR, AAV, HRY; Drafting of the manuscript: BA, AAV; and Study supervision: HR.

Ethical Approval

The approval of Ethics Committee of Jahrom University of Medical Sciences was obtained (code: Jums.REC.1393.001). Informed oral consent was also obtained from all the patients.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests. Financial Support

This work was financially supported by Jahrom University of Medical Sciences.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students at Jahrom University of Medical Sciences who participated in this research project. This work was financially supported by Jahrom University of Medical Sciences (Jums.REC.1393.001).

References

1. Steketee RW. Pregnancy, nutrition and parasitic diseases. J Nutr. 2003;133(5 Suppl 2):1661s-1667s.

2. WHO. Control of Tropical Diseases. Geneva: WHO; 1998. 3. Rokni MB. The present status of human helminthic diseases

in Iran. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102(4):283-295. doi:10.1179/136485908x300805

4. Saksirisampant W, Prownebon J, Kulkumthorn M, Yenthakam S, Janpla S, Nuchprayoon S. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among school children in the central region of Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89(11):1928-1933. 5. Kim BJ, Ock MS, Chung DI, Yong TS, Lee KJ. The intestinal

parasite infection status of inhabitants in the Roxas city, The Philippines. Korean J Parasitol. 2003;41(2):113-115.

6. Garcia LS, Bruckner, DA. Diagnostic Medical Parasitology.

3rd ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1997.

7. US CDC. DPDx: Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control Prevention; 2006.

8. Cox G, Francis E, Julius P, Wakelin KD, eds. Parasitology; 9th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999.

9. Mehraj V, Hatcher J, Akhtar S, Rafique G, Beg MA. Prevalence and factors associated with intestinal parasitic infection among children in an urban slum of Karachi. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3680. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003680 10. Kain KC, Pillai DR. Common intestinal parasites. Current

Treatment Options in Infectious Diseases. 2003;5:207-217. 11. Minenoa T, Avery MA. Giardiasis: recent progress in

chemotherapy and drug development. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9(11):841-855.

12. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth infections--preliminary estimates of the number of children treated with albendazole or mebendazole. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2006;81(16):145-163.

13. Chan MS. The global burden of intestinal nematode infections--fifty years on. Parasitol Today. 1997;13(11):438-443. 14. WHO. Geographical distribution and useful facts and stats.

Geneva: WHO; 2006.

15. Daryani A, Sharif M, Nasrolahei M, Khalilian A, Mohammadi A, Barzegar G. Epidemiological survey of the prevalence of intestinal parasites among schoolchildren in Sari, northern Iran. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106(8):455-459. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2012.05.010

16. Sayyari AA, Imanzadeh F, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Karami H, Yaghoobi M. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(3):377-383.

17. Arani AS, Alaghehbandan R, Akhlaghi L, Shahi M, Lari AR. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in a population in south of Tehran, Iran. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2008;50(3):145-149.

18. Haghighi A, Khorashad AS, Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E, Kazemi B, Rostami Nejad M, Rasti S. Frequency of enteric protozoan parasites among patients with gastrointestinal complaints in medical centers of Zahedan, Iran. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(5):452-454. doi:10.1016/j. trstmh.2008.11.004.

19. Nasiri V, Esmailnia K, Karim G, Nasir M, Akhavan O. Intestinal parasitic infections among inhabitants of Karaj City, Tehran province, Iran in 2006-2008. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47(3):265-268. doi:10.3347/kjp.2009.47.3.265 20. Omorodion OA, Isaac C, Nmorsi OP, Ogoya EM, Agholor

KN. Prevalence of Intestinal parasitic infection among tertiary institution students and pregnant women in south-south, Nigeria. J Microbiol Biotech Res. 2012;2(5):815-819. 21. Aksoy U, Akisu C, Bayram-Delibas S, Ozkoc S, Sahin S,

Usluca S. Demographic status and prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in schoolchildren in Izmir, Turkey. Turk J Pediatr. 2007;49(3):278-282.

22. Rezaiian M, Jalalian M, Kia EB, Massoud J, Mahdavi M, Rokni MB. Relationship between Serum Ige and Intestinal Parasites. Iran J Public Health. 2004;33(1):18-21.

23. Asgari G, Nateghpour M, Rezaian M. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in the inhabitants of islam-- shahr district. Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research. 2003;1(3):67-74.

24. Arbabi M, Talari SA. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in students of Kashan University of Medical Sciences. J Ilam Univ Med Sci. 2003;12(44, 45):24-33. [Persian].

25. Adungo NI, Ondijo SO, Otieno LS. Intestinal parasitoses and other infections in a college community. East Afr Med J.

1991;68(1):52-56.

26. Bennett JE, Hill DR. Giardia lamblia. In: Mandell GL, Dolin R, ed. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2007:2888-2893.

27. Quihui L, Valencia ME, Crompton DW, et al. Role of the employment status and education of mothers in the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in Mexican rural schoolchildren. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:225. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-225

28. Sharif M, Daryani A, Asgarian F, Nasrolahei M. Intestinal parasitic infections among intellectual disability children in rehabilitation centers of northern Iran. Res Dev Disabil. 2010;31(4):924-928. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.03.001 29. Yanagida J, Ishiyama S, Rai SK, Ono K. Study on Intestinal

Parasitosis among Public School Children in Kathmandu, Nepal. Bull Kobe Tokiwa Coll (Japan). 2004;26:55-8.

30. Uga S, Hoa NT, Thuan le K, Noda S, Fujimaki Y. Intestinal parasitic infections in schoolchildren in a suburban area of

Hanoi, Vietnam. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(6):1407-1411.

31. Nematian J, Nematian E, Gholamrezanezhad E, and Asgari AA. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and their relation with socio-economic factors and hygienic habits in Tehran Primary School Students. Acta Tropica. 2004;92:179-186.

32. Ostan I, Kilimcioglu AA, Girginkardesler N, Ozyurt BC, Limoncu ME, Ok UZ. Health inequities: lower socio-economic conditions and higher incidences of intestinal parasites. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:342. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-342 33. Wordemann M, Polman K, Menocal Heredia LT, et al.

Prevalence and risk factors of intestinal parasites in Cuban children. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(12):1813-1820. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01745.x

34. Karrar ZA, Rahim FA. Prevalence and risk factors of parasitic infections among under-five Sudanese children: a community based study. East Afr Med J. 1995;72(2):103-109.