1

Securitization of Migration in the European Union:

Mind your semantics!?

Gijs Norden Student number: 1013653 Leiden University Master Thesis Crisis and Security Management Supervisor: Prof. Dr. M. Den Boer Second reader: Dr. J. Matthys Word Count:

2 Table of Contents

1 Introduction………Page 3-4 2 Literature Review Page 4-9

2.1 Copenhagen School……….………...Page 4

2.2 Securitization Theory………..………...Page 5

2.3 World Risk Society………..………...Page 5-6

2. 4 Connecting Migration to Security……….………...Page 7-9

3 Theoretical Framework Page 9-17

3.1 Politics of Insecurity………...………...Page 9-10

3.2 Framing Migrants………..………Page 10-12

3.3 Spread of Trust and Fear………...Page 12

3. 4 Administering inclusion and exclusion………...Page 13 3.5 Structuring alienation and predisposition towards violence………..………...Page 13-14

3.6 Importance of Audience………..………...Page 14-16

3.7 Internal and External Security ………...Page 16-17

4 Case Selection Page 17-25

5 Research Method Page 25-31

5.1 Unit of Analysis………..Page 26-28

5.2 Different existential danger frames………...………...Page 28-30 5.3 Semantic Code Scheme for frames………..………Page 31

6 Findings Page 32-45

6.1 Dutch EU Presidency of 1997………...………...Page 33-36 6.2 Dutch EU Presidency of 2004………..………...Page 37-40 6.3 Dutch EU Presidency of 2016………...………...Page 41-45

7 Synthesis Page 45-53

7.1 Dutch EU Presidency of 1997………..…………...Page 46-48

7.2 Dutch EU Presidency of 2004………..………..Page 48-50

7.3 Dutch EU Presidency of 2016……….………...……Page 50-52

7.4 Comparing the Presidencies………..….Page 52-53

8 Final Conclusions and Discussion Page 53-58

8.1 Final Conclusions……...………..………..…Page 52-54

8.2 Discussion ………..………Page 54-57

9 Literature References Page 59-64

3

1. Introduction

During the Summer of 2015 there was an increase in the numbers of refugees applying for asylum in the European Union. Most of these refugees come from war torn regions such as Syria and Iraq (BBC 2015). These large numbers of people, asking for shelter and security, are a big challenge for the European Union and its Member States. In many states there are different opinions about how to deal with these refugees. There are also voices, in for example the

Netherlands, that portray these refugees as a threat to national security of Western States (Van Den Dool 2015). These groups of refugees are framed as a security issue because IS, allegedly stated that they would send terrorists and fighters among the refugees to disrupt European societies (Kaplan 2015). This leads to a securitization of refugees and migration in general. One could think that this process securitization of refugees and migrants is a completely new phenomenon, linked to this specific crisis. Others might think that 9/11 was a turning point and the beginning of portraying migrants as a security problem. However, this is not the case. Refugees and migrants have been portrayed as a threat to security far before these events, for example during the Yugoslavian wars during the 1990’s (Barutciski 1994, 32).

This thesis will look into the securitization of migration. It will look into framing by the Council of Europe of migrants and refugees, during three different migration crises. It will analyze whether and how migrants and refugees have been securitized during the European Union

Presidencies of the Netherlands. This will be done by analyzing different (policy) documents which were issued by the Dutch government as well as the Council of the European Union. The main research method is discourse analysis. It will analyze the (securitization) discourse during three successive Presidencies of the Netherlands of the European Union, namely in 1997, 2004 and 2016. Because the Presidency of 2016 of the Netherlands is still ongoing at the time of writing the Council of the European Union documents of the “troikas” of each Dutch Presidency will be taken into account, referring to EU Presidencies prior and after the Netherlands EU Presidency with the fixed duration of six months each.

4 compare different migrant groups overtime (Nickels 2007, 37). The theoretical background of this thesis will be mainly focused on the approach of Huysmans (2006). Huysmans can be placed in the more critical group of scholars of the Critical Security Studies (CSS). Huysmans’ theoretical

approach will be completed with the works of Bigo (2001), Balzacq (2005) and others, to include some of the framing theory and other aspects. The research question this thesis seeks to answer is: how do the Council of the European Union and the holder of the Presidency, namely the Dutch Government, frame migrants and refugees during the relevant Presidency terms? Moreover, when we compare these Presidencies, can we observe any successive shifts in the way migrants are framed as a security issue?

In the next section of this thesis the relevant literature concerning the securitization of migration theory will be discussed. Then the theoretical framework will be elaborated on. Followed by the research design, including the case selection and research method of this thesis. Finally, the findings, a synthesis and final conclusions and a discussion will be presented.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Copenhagen School

5

2.2 Securitization Theory

The securitization of migration is actually an application of securitization theory to the field of migration. Securitization theory has its origins in the work of authors such as Barry Buzan (1991). It is also closely linked to the abovementioned Copenhagen School. For example, Ole Weaver (1995) argued that security issues do not come out of the blue, but are constructed as such by securitizing actors through speech acts. Security (issues) can therefore not be seen as a given fact but it should be seen as an intersubjective discursive process (Tromble 2014, 527). Tromble (2014), adapts the definition of Buzan, Weaver and de Wilde, and describes the process of securitization as:

“The process of securitization is begun when an actor (or set of actors): (1) identifies something a referent object, as existentially threatened; (2) suggests that the source of that threat; and (3) calls for extraordinary measures – or departures from the rules of normal politics, such as secrecy additional executive powers and activities that would otherwise be illegal. The process of securitization is then complete or “successful” when the actor’s intended audience accepts all three components as given and itself perpetuates the securitizing discourse (Tromble 2014, 527-528)”.

There have been criticisms to this view because it is regarded as too narrow, by focusing only on speech acts of dominant actors (McDonald 2008, 563; Williams 2003). Others like Bigo (2002) and McDonald (2008) argue that also bureaucratic practices can also be important to take into account when studying securitization. Through the years the securitization theory has been adjusted and applied to many different fields. In the next section the connection between migration and securitization theory will be explained and elaborated on.

2.3 World Risk Society

In 1992 Ulrich Beck introduced the term (world) risk society. Almost a decade later Beck revisited his risk society theory. And added world to his concept of risk society in 1999. After 9/11 he argued that the world risk society was visible in nearly all global problems. Beck argues that

6 become more dangerous, but it means that uncontrollable risks have “de-bounded”. It is

uncontrollable on three different axioms, spatial, temporal and social. Spatial refers to the fact that modern risks do not stop at borders, they are often cross-border problems, such as large numbers of refugees, economic crises and climate change (Beck 2002, 41). In other words, national security is no longer national, it has become international because states have become interdependent and closely related.

In order to deal with for example international migration, it is necessary for (nation) states to cooperate transnationally (Beck 2002, 46-47). The temporal axiom means that the risks are stretched over a long period of time, which makes it hard to make policy for more than just the short term. The social axiom refers to the difficulty of determining who is responsible for causing the risks or problems, it is for example hard to determine the exact person who caused a financial crisis or who started environmental problems. Mainly because these problems are the outcomes of behavior of many different people (Beck 2002, 41).

Beck then argues that there are three different dimensions of conflict in the world risk society, ecological conflicts, global financial crises and global terror networks threats that have empowered governments and nation-states (Beck 2002, 41). Nowadays this terrorist networked threat has spread across the globe and together with wars and other conflicts have caused millions of people to search refuge in other countries. This new large migration problem is an aspect Beck has left out of his revisiting of the world risk society theory. But mobility was already a big issue that was linked to globalization, moreover human tragedies had already taken place, for example the Balkan crisis and for example ethnic cleansing in Rwanda. There are other authors who did

7

2.4 Connecting Migration to Security

However, migration has been recognized as a security issue. Copenhagen School Member Buzan (1991) was one of the first to connect migration and security to each other. Along with ecological issues, migration was one of the first fields to which the security nexus was broadened (Buzan 1997, 6-7). Before it was studied in relation to security, migration was mostly studied in the fields of sociology, anthropology and history (Huysmans and Squire 2009, 1). One of the first migration issues that was being securitized was even during the Cold War. It was argued that the migration flows of East German refugees contributed to bringing down the Berlin wall and that they

therefore had a big part in the erosion and finally the collapse of the German Democratic Republic. Thus the general argument goes that population flows can pose a threat to the security and

stability of nation-states and moreover the international order (Huysmans 2006 ,16). To prevent this state erosion due to migration and a possible collapse of their state, states like North Korea but also the German Democratic Republic prohibited their citizens to leave the country. These kind of measures are mostly found in totalitarian states. However, there are a lot of accounts that counter the argument that population flows can cause erosion and collapse. For example, these arguments say nothing about the stability of the hosting country, mostly about the country where people flee from. Moreover, population flows can often be absorbed into hosting societies, when they are willing to do so. Think for example about the internally displaced persons during World War 2 in Europe. But also the Belgian refugees in the Netherlands during World War 1 or the Jewish refugees in the 1930’s. Both groups were absorbed into Dutch society, although their absorption depended mostly on their social economic status (Laqua 2012, 480-81; Moore 1984, 75).

Some critics initially rejected the link, because they argued that the security discourse could have negative effects on migrants (Collyer 2006, 255). They argued furthermore that the link

8 and that it takes for granted the uniform rationality in explaining organizational action (Boswell 2007, 593). According to the securitization literature there are two ways in which organizations take part in securitizing, both underpinned by the assumption that they are power-maximizing. The first is that security agencies try to expand to other areas, they can do so by the legitimization by a security discourse in the public domain. The other way is that agencies try to expand their power by avoiding public scrutiny, by for example trying to go beyond national scrutiny by cooperating at the European level (Boswell 2007, 592-593). However, while Boswell acknowledges that securitization is often happening, she does not discard the theory in general. She adds that securitization should not be the starting point of research. She argues that researchers also have to take in mind that there are other possible ways of framing politics and mechanisms at work than just securitization (Boswell 2007, 59). Lavenex on the other hand argues that there is a big

normative aspect in refugee policies which have been developed in the European Union. There are tensions between internal security on the one side and human rights’ issues on the other side. Refugee policies cannot just be justified on the basis of material interests; it is mainly a normative policy. These policies are derived from universal human rights (Lavenex 2001, 852). In her work she focuses on the Europeanization of refugee policies. This entails the European integration agenda and especially the institutionalization of actions of the EU but also the institutionalization of meaning. Which means that ideational factors are becoming of vital importance as well as the procedural and institutional aspects (Lavenex 2001, 853).

Within the securitization of migration literature there have been different views, critiques and approaches. In the early 1990s most attention was given to states and their “original”

9 approach, he focuses his research on three basic assumptions. He argues that an effective

securitization has to be audience-centered, that it is context dependent and that effective

securitization is power-laden (Balzacq 2005, 171). Jef Huysmans is also a well-known author in the field of securitization of migration. He has published several articles, books chapters and books on the subject, including some on the normative dilemma of writing security1. In the next section on

the theoretical framework, the work of Balzacq (2005), Bigo (2001) and Huysmans (2006) and others will be combined and elaborated on. It will serve as the theoretical foundation for the analysis of the discourse of Dutch EU Presidencies during several refugee crises.

3. Theoretical Framework

As argued above, security threats and insecurities are not just given study material or given problems that need to be solved. They are the product of social and political practices. A theoretical approach that tries to understand how these practices work and what the social and political implications are of this, is securitization theory which is a part of critical security studies (CSS) (Voelkner et al. 2015, 1). This thesis uses the theoretical backgrounds of the critical security studies, and mainly securitization theory. It will build on theoretical contributions of Huysmans (2006), Bigo (2001), Balzacq (2005) and other academic authors to the securitization theory.

3.1 Politics of Insecurity

Huysmans for example makes a convincing case for the politics of insecurity. He argues that it can be a political danger to put something on the political agenda as a threat to security or to not do this. Politics of insecurity are thus not only concerned with policy reactions to an already defined threat or questions the degree and nature of this threat. Politics of insecurity is also concerned with contesting the use of security language in relation to particular subjects (Huysmans 2006, 7). But what is actually meant by insecurity? This question was answered by Béland (2007), he argues that (collective) insecurity is a social and political construction, that is actively promoted by policy makers and politicians. It means that personal and environmental matters are transformed into

1

10 social and political issues (Béland 2007, 320-321).

The focus on the use of security language is important because it can have implications for policy options. An issue that is framed as a (national) or (health) security issue may get more drastic governing solutions than when no securitization took place (Curley and Harington 2011, 142). When this is applied to the issue of migration we can see that cross border movement and the presence of aliens in a particular state often brings issues like political loyalties, calculations of the impact on the economy, military and other capacities of states, to mind (Huysmans 2006, 30). However, in order to pass policies on issues like migration it is necessary to get support, political actors can get support by using particular frames. The next paragraph will elaborate on the issue of framing in combination with migration.

3.2 Framing migrants

Framing is a concept that is most often linked to the media. But frames are not only used by the media but are, for example, also being used by politicians and policy makers. Either through the media or through their own forums like personal, and party websites or government websites. Framing is “the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an issue” (Chong and Druckman 2007, 104).

There are two main types of frames, namely frames in thought of the individual and frames in communication. The first refers to set of dimensions that affect the evaluation of an individual towards a particular subject (id. 2007, 105). This thesis however will focus on the frames in

communication. Because these are the frames that are often used in politics and by policy makers. According to Jacoby (2000) politicians try to attract voters for their policies by persuading them to think about their policies along particular lines. They can do so by focusing on specific features of their policies. For example, stressing the likely effects or the relationship of the policies to

important values of the audience (Jacoby 2000, 751). So frames give specific definitions and interpretations of political issues for a specific, or the general audience. In other words, they try to guide the audience with a specific frame to perceive and interpret matters and events in a specific way (Shah et al. 2002, 343).

11 politicians and policy makers. By doing so it becomes easier for them to promote political

autonomy and unity (Mehan 1997, 253-254; Huysmans 2006, 50).

Refugees and migrants are often framed as a danger to the survival of political units, such as specific communities, states or regions. This danger can occur in different ways. For example, by numbers, when there is a sudden large increase in immigrants. These large numbers of migrants can be framed as that they will disturb the labor markets of states which can cause popular unrest. Governments like to avoid popular unrest and therefore they will make policies to prevent these unrests (Jørgensen and Meret 2012, 293; Huysmans 2006, 47). Politicians often use or refer to strong wordings that are used, such as ‘flood’ and ‘invasion’ of immigrants. These words cause the public to think they are in existential danger, which can be the path towards the legitimation of particular measures and policies. Not only numbers of migrants are used for securitizing arguments. The specification of characteristics, and cultural differences of immigrants and refugees in comparison to the hosting state or society can be used to frame them as an existential danger to this hosting society or community (Ceyhan and Tsoukala 2002, 24-26).

Even though these aspects are important to the securitization process, Huysmans argues that they are mostly uneases but do not necessarily in themselves mean an existential danger to the survival of a political community or a state. It is mostly not the state that needs to be secured, but the ‘autonomy of the community as a political unity, often defined in terms of its independent identity and functional integrity’ (2006, 48). Which means, as said above that linking these uneases to an existential situation is mostly a political choice.

12 it easier to define who is an outsider, a migrant or even an illegal migrant (Ceyhan and Tsoukala 2002, 24-25; Mehan 1997, 258-259). This makes it easier for politicians and policy-makers to portray their own state as a complete and harmonious place that is then being threatened and frustrated by for example migration. The only solution then seems to be to get rid of this existential danger of migration which will then supposedly help restoring a peaceful and free political entity (Den Boer 1998, 3; Mehan 1997, 258-259; Huysmans 2006, 49).

Security framing can lead to the creation of an autonomous domain of politics that claims unity, and therefore a division between us and them, this happens by three different strategies, the spread of fear and trust, the conduct of inclusion and exclusion and finally the institution of alienation and a predisposition towards violence (Huysmans 2006, 51). These three different strategies will be elaborated on below.

3.3 Spread of Trust and Fear

Security framing creates domains of political interaction by spreading trust and fear. In the case of migration this can mean that we trust those who are (culturally) close to us, (Western, European) and fear those who are at distance of us (Non-Western, Non-European). Thus it can mean that these people that are at distance of us can disturb cultural identities that are similar, for example, Muslim identity politics versus the liberal states of Europe. Some argue that they are incompatible (Adamson and Triadafilopoulos and Zolberg 2011, 850-851). This is often reflected and integrated in and a part of policies for the assimilation and cultural integration of immigrants. The danger of this is that immigrants that are less able to assimilate, can easily be politicized into outsiders that should be feared. It can then be created indirectly by creating a negative frame of the ‘others’. For example, by systematically referring to Islam as a threat. This implicitly reasserts the Christian West as opposed to Islam. Thus trust can be achieved through identifying or creating sources of fear or distrust. In this way we know who to trust and who to fear. In this way politics of

13

3. 4 Administering inclusion and exclusion

This strategy is about how the instrumental or governing side of security practice layers relations and administers inclusion and exclusion. There are different ways to deal with existential fear. One of them is to reduce the vulnerability or tackling the danger itself. Security policies are mostly directly and explicitly linked to a strategy of distancing from and neutralizing threats. For

example, defining borders and boundaries. But also Having intensified border controls can create distance between a society and the dangerous external surroundings (Buonfino 2004, 41). But also the use of technology and registration, special ID cards for refugees and immigrants can internally distance them from the host population. An even more drastic measure can be the detainment of refugees who are still in the process of getting a refugee status or refugees who do not meet the legal conditions of a host country and who are to be deported (Bigo 2006, 394). By creating both physical and symbolic distances between the host population and the migrants an atmosphere of inclusion and exclusion can easily be developed.

3.5 Structuring alienation and predisposition towards violence

The process of including and excluding is very vulnerable to intensifying constantly. The

securitization only makes the including and integration with outsiders more difficult. Huysmans brings up the example of guest workers who never fully belonged to their new surroundings but were integrated socially and economically. They were never seen as a danger. People were mostly indifferent to them. The process of securitization has portrayed these people a danger to the culture, public order and welfare provisions to which they contributed themselves by years of hard work. It seems to have also lead to ethnic profiling of ethnic minorities and migrants in general (Van der Leun and Van der Woude 2011, 445; Huysmans 2006, 57). By framing or seeing migrants as a danger to society, it makes it easier to enhance negative feelings towards

immigrants. Which can lead to a call for more restrictive migration policies that need to protect the independent identity and functional integrity of a state (Huysmans 2006, 57). These migration policies are then becoming stricter and more sophisticated as migrants become more innovative in avoiding the measures. People can then get an image of refugees and migrants as being not

14 The aspect of violence is also often invoked in relation to migrants. For example, youth from migrant background from more backward neighborhoods are often associated with images or rioting, violent criminality and other forms of violence (Van der Leun and Van der Woude 2011,445). But also migration is often linked to violence and war (Huysmans 2006, 59). However, Huysmans argues that these extreme securitization views and policies compete in political arenas with views supporting the continuing of immigration to cope with declining populations. And that securitization language is part of the political game to evoke or perpetuate crisis situations,

emergencies enemies and dangers for political gain. However often they do also offer reassurance by showing that they do something about it with (restrictive) policies. By perpetuating and evoking crisis situations, politicians and policy makers can also legitimate their policy plans and ideas. However, this of course cannot be undertaken without a perceptive audience. The next subsection elaborates on the importance of audiences for the securitization process.

3.6 Importance of Audience

Balzacq (2005) argues that securitization is better understood as “a strategic (pragmatic) practice that occurs within, and as part of, a configuration of circumstances, including the context, the psycho-cultural disposition of the audience and the power that both speaker and listener bring to the interaction” (Balzacq 2005, 172). Moreover, the author proposes that the audience, political agency and context are crucial for an analysis of securitization and that these should not be overlooked. He disagrees with the view that securitization can be seen as just a speech act. In which a speech act becomes effective from the act being done (Balzacq 2005, 176). He argues that external factors, such as audiences matter as well. But Balzacq does not explain in detail how the audience should be convinced of the message of the policy makers and or politicians, he does not elaborate on the level of persuasiveness. Mehan on the other hand argues that the securitization process can be seen as a speech act. She refers to the fact that “words of a Khomeini, a Stalin, a Hitler have power: they have mesmerized and electrified, reminding us that words can have a diabolic as well as a liberating and activating power (Mehan 1997, 251). Although Balzacq tries to modify the CS security studies’ theory he does not reject it at fully. He argues that he is only trying to strengthen it, by adding variables that have been neglected (Balzacq 2005, 179). However, he does, as argued above, ignore the variable of perception, receptiveness and potentially

15 To convince an audience of your security message it is necessary to relate the statement to an external reality (Balzacq 2005, 182). The success of securitization depends on a perceptive

environment and or audience. A security actor has to decide what the right (critical) moments are, in which, the susceptible audience will be easily convinced by his message of securitization (De Graaf 2011, 63; Balzacq 2005, 182). This means that the speech act has to be an intentional, rational and discursive act. Austin (1962) with his speech act theory goes into this matter in more detail. Austin argued that words can actually count as actions. He makes a distinction between

performatives and constatives. Constatives are statements that can be seen as being either true or false. Performatives on the other hand cannot be seen as such. Performatives can be defined as words that actually count as performance of an action. These words can either be felicitous or infelicitous (Emike 2013, 241). Another related concept is the perlocutionary act, these acts are “the effects on, or thoughts or feelings of the audience or the speaker produced by the act of saying something”. Austin then makes a distinction between the act of doing something and the act of attempting to do something (Emike 2013, 242). Perlocution is thus central to understanding how a particular issue can become a security problem. By using securitizing words an actor intentionally chooses to convince its target audience in a particular environment or circumstances.

When actors try to securitize an issue they often try to convince as broad an audience as possible because they have to keep a social relationship with the group they are targeting their message at (Balzacq 2005, 185). They try to obtain both moral support from the general public and their institutional body. They need especially the latter party for formal support, to get issues through parliaments or other legislative and decision-making bodies (Balzacq 2005, 185). It thus needs to be noted as well that audiences do not necessarily have to be the general public. The audience can also be the power elite or put simply, other politicians. Audiences have to be able to provide a securitizing actor with whatever he or she seeks to accomplish with the securitization process (Vuori 2008, 72); for this thesis the target audiences are be the ministers that are a Members of the Council of the European Union, Members of Dutch Parliament as well as the general public. Vuori argues that in crisis situations securitization processes can be restricted to inter-elite audiences and struggles, for example politicians in different political arenas such as parliament and EU

ministerial consultations (Vuori 2008, 72).

16 convinced by the securitizing actor. This depends on the whether this actor is trustworthy and knowledgeable on the matter. Finally, the audience needs to have an ability to grant or deny the securitizing actor a formal mandate to implement their (possible) measures (Balzacq 2005, 192). As for the context of a security frame it is important that it fits the what Balzacq calls “Zeitgeist”. The audience has to see how the securitization fits in the bigger picture of the Zeitgeist. Finally, the securitizing actor needs to be able to use the proper words and frames that fit the context (Balzacq 2005, 192). But also in some way needs to indoctrinate the masses with the rightness of their story and frame, in order for them to act (Mehan 1997, 251-252). Thus a successful securitization process can only be achieved when the actors and their relative power, their expressions and discourse (speech acts) have a susceptible target audience that get the feeling that they should act and implement policy on the speech acts of the securitizing actor (De Graaf 2011, 63).

3.7 Internal and External Security

Several authors argue that a merging of internal and external security has taken place. Contrary to what is often argued, this merger between internal and external security has not been due to criminalization of war and militarization of crime, which is often argued (Bigo 2001; 2006; Lavenex and Wichmann 2009; Lutterbeck 2005). Bigo states that internal and external security are mixed duo to a 1) transformation of the social world, 2) the ways in which different agencies construct these changes as threats (such as migration), 3) their interests in the competition for budgets and missions and legitimacy and 4) the way in which political, bureaucratic and media games do or do not construct social change as a political or security problem (Bigo 2001, 121).

Furthermore, the discourse on migration is positioned in competition with other issues in the hierarchy of threats. A general trend that could be observed is that migration is not only seen as a problem at the national level of states, it is also seen as a problem internationally, especially for Western states (Bigo 2001, 121; Lutterbeck 2005, 233). In most political spheres the actors agree that migration is a problem for both internal and external security. Often the migrant in general is linked to all kinds of criminal behavior such as, drug trafficking, Islamic radicalism, organized crime, human trafficking and terrorism. The Western world regards transnational flows of people more and more as a danger to their political, economic and social welfare. International

17 security issue on the international agenda. Even though smaller countries, such as the Netherlands and Sweden and Spain have tried to change the hierarchy of issues of the G8 during the 1990s, nowadays these countries also seem to have incorporated migration as a security problem, as reflected in the Schengen agreement (Bigo 2001, 123-124). We can thus see that the balance of power is also reflected in topics such as migration, the more powerful states put topics on the agenda and the less influential states (eventually) will follow this agenda. In the next chapter the methodology of this thesis will be presented, with an elaborate description of the Presidencies and the backgrounds of the coinciding migrant crises.

4 Case Selection

4.1 Case Selection

For this research the Dutch EU Presidencies are being analyzed, because the Council is one of the formal law and policy making bodies of the European Union, and as a Member of the European Union the Netherlands takes on the role of the Presidency of the Council of the European Union once every few years. The Presidencies of the Netherlands were chosen for both practical and theoretical reasons. For example, a linguistic advantage and because the Netherlands is a small EU Member State but also one of the founding fathers of the European Union. Because the

Netherlands was one of the first Member States it has a lot of experience in organizing EU Presidencies. This makes it easier for policy makers because they can build on previous experiences. As for example the Italian bureaucratic institutions benefitted from previous Presidency experiences during the preparations for the Italian 2003 Presidency (Quaglia and Moxon-Browne 2006, 352). However, politicians are not always able to capitalize these experiences. For example, because they were not in office during the last EU Presidency of their country, but also because, after the enlargement of the EU, there are more Member States which makes the intervals between Presidencies wider.

193-18 194; Van Keulen 2006, 13). Therefore, the Netherlands seems the perfect candidate to take into account, because it is both one of the smaller countries within the European Union and it has been one of the countries that received a good share of refugees in the past and at the present day (Vluchtelingenwerk.nl 2015). For example, a Member State like Belgium is giving shelter to about 29.000 refugees while the Netherlands had received 40.000 refugees by the end of May 2016 and is expected to receive 90.000 over the whole year of 2016 (Fedasil 2016; Volkskrant 2016). In the next paragraph we will elaborate on how the EU Presidencies of the Council of the European Union work, what its obligations and procedures are and how the EU Presidency can influence EU policies and law-making.

EU Presidency of the Council of the European Union

Every six months one of the Member States of the European Union takes on the Presidency of the Council of the European Union. The responsibilities of the Presidency are established in the Treaty of the European Union. The Presidency's tasks entail for example, that the relevant Member State presides all Council meetings, except those on foreign affairs. The President has to report to the European Parliament. In sequences of 18 months three Member States will be selected, in specific order, to be President of the Council, these three are often called the troika or trio (Council of the European Union 2015, 10-15). The importance of the rotating Council Presidency has increased. The Presidency is now a functional and accountable element of EU policy making (Vandecasteele and Bossuyt 2014, 233). The Member State that takes on the Presidency, of course also has to prepare itself for the Presidency at the national level. It puts a lot of weight on the shoulders of ministries, especially of the smaller states. Ministries sometimes suffer from wanting to do too much in too little time. This then results in a bad allocation of resources and in the agenda being overloaded with issues, which can annoy other Member States (Schout and Bastmeijer 2003, 14). But when a Member State is well-prepared the efficiency of the meetings will increase (Schout and Vanhoonacker 2006, 1060). It will help officials to see what steps should be taken and what to be avoided. This can involve mapping out important issues at an early stage, intensive contact with other Member States, presenting papers on the different topics or structuring the debates (id 2006, 1062-64).

19 Lisbon Treaty (Raik 2015, 20). The troika or trio has to establish an 18-month programme for their term beforehand. This programme has to be approved by the Council as a whole. The troika programme entails an introduction with strategic long term policies of the Union, an operational section with the activities of the Council for the period of 18 months (Council of the European Union 2015, 17). In order to have consistency in policies, a good coordination and smooth transitions from one Presidency to the next is necessary.

Every EU Presidency has several obligations. The Presidency has to update the different files during their six-month term, time frames and schedules for procedures of the parliament and other institutions have to be taken into account. There needs to be an evaluation of the importance of each file or issue and their political or technical implications. Consistency in terminology and presentation is important as well (Council of European Union 2015, 19). To guide this consistency from one Presidency to the next the council Secretary has an important role. It supports the President in their duties and do some administrative work (Raik 2015, 33). Besides the formal mechanisms the troika also experiments with new and additional obligations. For example, some Member States invite an incoming President candidate during their Presidency to the meetings with the European Parliament, or inform them about the negotiations, in order to prepare them for their task and to have more consistency. Other ideas are shared training and spreading the

informal ministerial meetings over the 18-month period instead of each Presidency of six months (Raik 2010, 32-33).

20 In the next paragraph this paper will elaborate on the three successive Dutch Presidencies of the European Union and the three refugee crises that coincided with the three Dutch Presidencies of the Netherlands.

Dutch EU Presidencies during three different refugee crises

As Balzacq argued, it is important to see significant events and especially securitization processes in their Zeitgeist. Therefore, in this section some academic evaluations of these Presidencies will be presented and the backgrounds of the refugee crises that were ongoing at the time of each

Presidency will be elaborated on. This in order to give the reader a basic idea of both the Zeitgeist during the crises and the possible causes and events of the crises

EU Presidency of the Netherlands in 1997 during the Balkan Refugee Crisis (1991-1999)

In January 1997 the Netherlands took over the Presidency from Ireland. This was during the final stage of the Intergovernmental Conference, which had the objective, to revise the Maastricht Treaty of 1991. It was important for the Netherlands to make the final summit in Amsterdam on this topic a great success in June 1997 (Van Keulen and Rood 2003, 71). The Netherlands has always been regarded as an active Member that has tried to push for further integration (Elgström 2006 186-187). According to Van Keulen and Rood the Dutch Presidency of ’97 has to be seen in the light of the Presidency of 1991. During the 1991 Presidency a proposal of the Netherlands for a new treaty was rejected, this casted a shadow over the entire Presidency of 1991. And for the 1997 Presidency the Dutch became less ambitious and more modest (Van Keulen and Rood 2003, 72-73). During the 1997 Presidency Migration and Asylum were no top priorities for the Netherlands. But the implementation of the Dayton Agreements was of some importance after the three main priorities, concluding the IGC, preparing the final stage of the EMU process and the EU enlargement. However, the modest agenda received criticisms from both the national and European parliament for being too modest and not having any clear vision at all (Elgström 2006, 187; Van Keulen and Rood 2003, 75).

In sum according to Van Keulen and Rood the Dutch Presidency of 1997 can be evaluated as a modest and pragmatic. But it needs to be noted that an important treaty, namely the Amsterdam Treaty was carried through during this specific Presidency. Which can be considered as a

21 treaty changes. Before the Lisbon Treaty, which entered into force in December 2009, these

conferences were the only way to revise treaties (Consillium.europa.eu 2016). So in 1997 the IGC was an important meeting for the Member States, because it was the only platform where they were able to debate and discuss changes to treaties. And the fact that during the Dutch Presidency, the Amsterdam Treaty was carried through can be seen as a major success.

Backgrounds of the Yugoslavia Wars

During the Presidency of the Netherlands of 1997, which took part between January and June, the height of the Yugoslavia refugee crisis was over. But still large numbers of former Yugoslavian refugees were entering the European Union. Yugoslavia had fallen apart into different other states such as Bosnia Herzegovina, Slovenia and Macedonia that wished to be independent from the mother state. The war has been called “the worst bloodletting since World War II” (Stokes et al. 1996, 136). Tensions in Yugoslavia were already rising during the 1980s when Serbian nationalism was upcoming after the death of communist dictator Tito who held the country together under his strict regime. According to Stokes et al. (1996, 138) three problems were at the core of the collapse of the Yugoslavian state, the inability of the Army to include all ethnic groups, the unrealistic wish of the communist party to keep political control and severe economic problems. Hundreds of thousands persons fled and tried to find asylum in other European countries (Suhrke 1998, 397). By 1993 about 600,000 Yugoslavian refugees had entered the European Union despite visa restrictions and other legal hindrances of European states (id. 1998, 407). During the crisis a 'sharing of the burden' was proposed by states that were most affected by the refugee crisis. For example, Germany, Sweden and Austria (id. 1998, 408). The fact that, at that time, this was the biggest refugee crisis in Europe, since World War 2, makes this case a noteworthy and interesting case to take into the analysis. These are two basic requirements for case studies proposed by Vroomen (2010, 256).

EU Presidency in 2004, Afghan refugees fleeing the Afghanistan War (2001-2010)

22 economy, 3. further development of the areas of freedom, security and justice, 4. Financial

prospects for the coming years and finally 5. working on the EU external relations. Next to these five main priorities there was also much attention for the ratification of the Constitutional Treaty on the European Union (Van Keulen and Pijpers 2005, 5). However, this Presidency was not as modest and pragmatic as the 1997 Presidency. It did have national aspects such as water

management, flooding initiative and maritime transport. But also the launch of a normative debate on ‘norms and values’ of European integration (Van Keulen and Pijpers 2005, 5). As freedom, security and justice was one of the main priorities, an ambitious plan were made for burden sharing among Member States for the issue of refugees.

23

Background of the 2001 Afghanistan War

In 2004 the Netherlands took the EU Presidency from July to December. During that time the United States and the Coalition of the Willing were at war with the Taliban and Mujahedeen in Afghanistan. The Taliban gained power after the Cold War. During the Cold War the Soviet Union supported a Communist Regime in Kabul. But after this communist regime fell, the Taliban gained power over the territory during the power vacuum that was caused due to the fall of the

communist regime in Kabul. The Mujahedeen and the Taliban received support during the Cold War from the United States. For example, they were supported with weapons such as Stinger anti-aircraft missiles and financial aid (Cogan 1993, 76; Kuperman 1999, 219).

The Taliban then ruled over Afghanistan and installed a strict Islamic republic based on Sharia law. The regime restricted women in their freedom and violated human rights. The Taliban was able to rule their territory without let or hindrance until the American-led invasion in 2001, which was a part of the Global War on Terrorism which started after the attacks of 9/11. As a consequence of this war many Afghans fled their country. Many went to neighboring countries such as Pakistan and Iran.

24 EU Presidency of the Netherlands in 2016 during the Syrian refugee crisis (2011-present)

At the time of writing of this thesis, the Dutch EU Presidency 2016 was still ongoing and therefore there was no scientific evaluation literature available yet. However, some scientists and think tanks published some preliminary articles on the Presidency. The Dutch EU Presidency of January until June 2016 had four main priorities: Europe as an innovator and job creator, stable finances and a stable Eurozone, a forward looking energy and climate policy and finally migration and

international security. Half way through this Presidency, Senior Research Fellow Adriaan Schout (2016), of the Clingendael Institute, wrote an article on the Dutch Presidency of 2016 that was both published on the website of the Clingendael and a Dutch newspaper. He argued that the Dutch received general acclaim for their European Presidency. The Dutch are praised for the energy of the different Ministers and especially the Prime Minister. But, there were also some criticism, for example the Dutch have lost their image of the European frontrunner, after the Eurosceptics gained popularity and because the first government of Prime Minister Rutte was supported by the right-wing and Eurosceptic Geert Wilders. Schout argues that the European Union lacks good leadership, which is now essential. Therefore, most EU negotiators and policy makers are very happy with the energy that Rutte is showing. He is being praised by his colleagues and for

example the President of the EP Schulz and Jean Claude Juncker. It seems that the Prime Minister Rutte has a clear vision to solve problems at the European level. However, it remains unclear whether the Presidency will achieve all its goals (Schout 2016).

Background of the Syrian refugee crisis

25 extremely complicated conflict has made many people refugees and or homeless (Fargues and Fandrich 2012, 4). By March 2013 around one million Syrian refugees were registered by the UNHCR, most of them sought refuge in neighboring countries (Syrianrefugees.eu 2013). Only a few months, in September, later this number already doubled to two million refugees

(Syrianrefugees.eu 2013). In July 2014 the total number of refugees went up to over three million, however Europe accepted only 100,000 refugees. Most of the refugees were still staying in the neighboring countries such as Lebanon (Syrianrefugees.eu 2014). However, the number of refugees that came to Europe grew rapidly over the years. In 2015 about 1 million refugees of which over 350,000 were Syrian refugees reached Europe (BBC 2016). This makes it an even bigger refugee crisis than the Balkan refugee crisis of the 1990s. The size and intensity of the crisis makes this case noteworthy and interesting enough to study in depth.

5. Research Method

For this thesis the research method of discourse analysis will be used. Discourse analysis is a research technique in qualitative research. It focuses on the use of language in policy making by looking at how for example questions are framed and asked. Actually almost all qualitative research makes use of discourse analysis in some way (Babb et al. 2012 ,351).

Discourse analysis does not only analyze words or language used in texts but it also looks at the overall strategy and impact of words. It also looks at how they are being used to shape a political understanding of a situation, or how language is used and manipulated in policy making. It thus looks both at how it is written and what is implied or not said. This makes it different from content analysis that mainly focuses on what is written in the text. Discourse analysis can help to examine how concepts are expressed, including the emotive and pejorative contexts. It is therefore an intensive approach that can only focus on a small number of key texts (Babb et al 2012, 351-352). There are many different approaches in discourse analysis. But the two main types are the

26 analyze texts are not necessarily derived from theory, but may be the result of empirical induction, e.g. through participant observation. However, such an ethnographic field method does not suit this specific thesis (Babb et al 2012, 356-357).

Therefore, for this thesis it is most suitable to use the functional discourse analysis. Because this type of discourse analysis tries to find discourse that matches the concepts and categories that are mostly derived from theoretical approaches (Babb et al. 2012, 356). In this case the theoretical backgrounds of Huysmans and others. It also helps to identify the groups or individuals that will be under analysis. It is important to identify and select discursive texts or speech acts which can be considered as representative of the individuals and groups that are being studied (Babb et al 2012, 358-359). In this regard, it is of utmost importance that the researcher maintains his or her

neutrality and explains the criteria on the basis of which the material was collected and selected for further analysis. Even though we acknowledge that discourse is a wide concept which entails speech acts but also non-verbal communication, diction and pronunciation this thesis will narrow the concept of discourse to semantics (Vuori 2008, 74; Emike 2013, 243). This because of practical reasons and limitations, such as non-availability of older speeches of Ministers. It will mainly look into what securitizing words are used in policy documents, regulations and parliamentary

discussions, and will not take into account diction, pronunciation or non-verbal communication.

5.1 Unit of Analysis

For this thesis the Presidencies of the Netherlands for the European Union will be taken as the main focus point. Official (policy) documents will be analyzed for securitization of migration discourse. Especially the Council of the European Union documents during the full term of the troika will be analyzed, this because Member States work together on the Programme of the Presidencies. The documents of the Dutch government that will be analyzed are mainly letters of the Government to parliament, but also State of the European Union documents and Public consultation documents. The documents of the Council of the European Union that will be analyzed are the directives, regulations, decisions and joint actions. All these aforementioned documents, that were produced by the Council of the European Union during the full period of the “troika”, that are related to migration and or refugees, are taken into account.

Document selection

27 the documents. For each Presidency the terms: “Migration 1997”, “Migration 2004”, “Migration 2016” and “Refugees 1997”, “Refugees 2004” and “Refugees 2016” were used. Then the results were refined by selecting the years “1996”, “1997”, “2004”, “2005” or “2015”, “2016”, two years were selected that overlap with the troikas of the Presidencies, furthermore the author “Council of the European Union”, and the option legislation was selected. Then the results were filtered for being related to migration, asylum(-seekers) or refugee(s), all other documents were omitted. All the final results were then downloaded into pdf files. The EUR-Lex website has a very convenient and easy to use search engine, so it did not cost a lot of effort and time to find the right documents for the analysis. For the Dutch EU Presidency of 2016 the documents were selected up to 31 May 2016, which leaves only the last month of the Dutch Presidency of this particular year out of the analysis. But in May there were no documents published on migration and refugees, so therefore there are no documents of this month reflected in the findings section.

For the Dutch Governmental documents on the EU Presidencies, the website

www.officielebekendmakingen.nl was searched for the words “Voorzitterschap Europese Unie”,

followed by the different years “1997”, “2004” and “2016”. Then the programmes of the Dutch government for the Presidencies of each year were downloaded in pdf files. Because the initial search for Presidency of the European Union in combination with the terms migration and

28 namely 4 (one General Consultation document, the Presidency Programme, and two letters to Parliament), it was best to make the same selection for the other Presidencies. So for each

Presidency one General Consultation, the Presidency Programme and two Letters to Parliament were selected. For the years 2004 and 2016 the State of the Union was included as well. So for these two Presidencies a total of 5 documents were selected that are both related to the Presidency and to migration and refugees. In the next paragraph four different frames are presented. These frames will be used as the basis for the analysis of the different documents that were mentioned above.

5.2 Different existential danger frames

As Huysmans (2006) argued migrants and refugees can be framed as an existential danger to the survival of the political entity. This frame entails that words are being used to describe refugees as a direct threat or danger to the state or region. For this master thesis four different frames will be analyzed and applied to the case of Dutch Presidencies of the European Union.

1. Public Security Frame

This frame is used to argue that uncontrolled (im)migration and especially refugees pose a threat to public order and social stability (Balabanova and Balch 2010, 384). Therefore, to deal with this 'threat' it is easier to implement new, and often much stricter, policies in order to prevent social instability. Balabanova and Balch (2010, 394) then argue that this kind of frame often results in policy makers and politicians making exaggerated and or spurious links between crime and refugees or migrants in general. This can then have a negative impact on refugees and migrants, because it becomes easier to pass legislations and measures to counter the threat and therefore they can be more easily put out of society, this then reveals the second frame of the us versus them frame.

2. Us versus Them Frame

29 and the hosting states and specification of characteristics of refugees to create a deeper division (Triandafyllidou 2000, 375-376; Huysmans 2006, 48). This frame also closely linked to the strategy of spreading trust and fear and of administering inclusion and exclusion that Huysmans

distinguished. The frame of them vs. us combines the two strategies, because both help to make a distinction between the receiving community and the refugees by both spreading trust among the community and fear for the refugees by referring to them as culturally and ethnically different. Which then helps administering inclusion and exclusion by implementing measures like special ID cards, or food stamps (Huysmans 2006, 51-55).

3. Numbers Frame/Uncontrollability frame

This frame is used to portray refugees as numbers, as large groups of unknown and most

importantly uncontrollable flows of people. This frame reduces the individual refugees to numbers and strong wordings like crisis, flow, hordes, influx, wave, invasion or flood are used to describe the refugees. According to these metaphors, just as we have no control over things such as the speed and direction of physical forces, we have no control over changes in our lives and communities. By using words, that refer to high and uncontrollable numbers of migrants or refugees, policy makers and politicians can give the idea of migrants causing popular unrest (Cunningham-Parmeter 2011, 1580). Which governments always try to avoid and therefore they implement stricter policies on migration (Huysmans 2006, 47). The use of these words invokes an idea of emergency condition with the audience. Governments are then of course expected to react to these imminent emergency conditions (Jørgensen 2012, 51). So by using the numbers frame it becomes much easier for governments or other governing entities such as the European Union to implement particular policies that help to cope with the issues at hand. The use of this frame can also be used to frame the problem being uncontrollable and unable to govern for governments.

4. Genuine refugee vs illegal immigrant

30 that this ascription of refugees has become embedded in immigration discourse (Den Boer 1994, 100).

31

5.3 Semantic Code Scheme for Frames

Frame Wording/Semantics

Public security frame Migrants are a threat to public safety and especially social (economic) security. Relations are being made between the migrant or refugee and criminal offences and criminal behavior. Refugees or migrants are linked to crimes such as human trafficking, terrorism and other crimes.

Us vs them frame Making a clear distinction between the migrant and or refugee and the community or society at large. Using words like “here”, “we” and “us” “them”. Mentioning cultural differences between

refugees/migrants and hosting community, calling for measures such as special ID Cards, food stamps, special visas.

Numbers frame Using words like Crisis, flow, tsunami, wave, hordes, influx, invasion, flood, to describe the refugees as being in overwhelming numbers and an immediate response is necessary. The policy is thus justified by the overwhelming numbers

Genuine refugee vs illegal immigrant Clear distinction is being made between genuine refugees that comply with definitions posed by international law and treaties and illegal

immigrants. Words that are generally used include: “irregular”, “Illegal”, “Unauthorized”, “Economic”.

32

6. Findings

In the paragraphs below the findings of this research are shown in the different

tables. Each Dutch EU Presidency has two tables, one for the Dutch Governmental

documents and one for the Council of the European Union Policy documents. Before

the findings are presented it is instructive to explain how they are structured:

1. In each table the columns reflect the different frames and the rows reflect

the different documents. The marks in the cells show what frame(s) were used in

what document.

2. Then in the paragraph below the tables the content will be elaborated on. Of

each frame, found in the documents, an example will be given by a quote from the

text.

3. Subsequently it will be explained why this quote matches this particular

frame. For the Dutch government documents that were not in English, a translation

by the author of this thesis is provided.

As mentioned in the document selection paragraph, during the Presidency of 1997

not that many documents were published on the Dutch Presidency by the Dutch

Government. Hence, only four documents were analyzed. For the other two

Presidencies five documents were selected, that are comparable with the four

documents of 1997. Two Letters to Parliament, one General Consultation, the

Presidency Program and the State Union

2. For the Dutch government documents the

frames of each document will be elaborated on because there are five documents per

Presidency. Whereas for the Council of the European Union documents there are

2 Not to be confused with the State of the European Union, the State of the Union is a document of the Dutch

33

more than ten documents per Presidency which would make the findings section far

too long. So for this section only a few quotes and explanations are presented.

6.1 Dutch EU Presidency of 1997

Table 6.1 Dutch Governmental documents Frame

Document

Public Security Frame

Us vs. Them Frame

Numbers Frame Genuine Refugee vs. Illegal Immigrant No Clear Framing or Other Frames General Consultation January 1997 #189 X Presidency Programme 1997 3

X X

Letter to Parliament November 1996 #1

X X

Letter to Parliament November 1996 #6 X Table 5.1 shows that most documents had no clear framing. However, when frames were used the genuine refugee vs. illegal immigrant frame was used most. In the Dutch EU Presidency Programme document the public security frame was used as well. Below the documents will be elaborated and commented on.

The first document, that was analyzed, is the General Consultation of January 1997. During the General Consultation the Dutch government discusses its plans for the Presidency of the European Union, in the Second Chamber. The Second Chamber is seen as the most

influential Chamber of the bicameral Dutch system (Andeweg and Irwin 2009, 146-47). In this particular document there are a few references to the Yugoslavia war, for example in relation to the capturing of war criminals. But the government does not directly talk about

3 This programme was not a separate document, as explained in the Operationalization, but was a section of

34 refugees or migration in general. The Minister ignored the question of a Member of the Parliament who asked whether the government agrees that the success of the London conference depended on the readmission of former Yugoslavian refugees to areas where their ethnic group is a minority (Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal 1997, 8).

The Presidency Programme for 1997 states that in order “to enhance (public) security, further

cooperation is needed in the fields of policing, judicial, customs, refugee and immigration cooperation”

(Tweede Kamer 1996, 5). By stating this, the government makes a clear link between (illegal) immigration, refugees and public security. It does so by making an explicit linguistic link between criminal activities, for which the policing and judicial services are accountable and the refugees, immigration policies on the other hand.

Sending (former) refugees back seems to be a really important issue during the 1997 Presidency. Both in governmental documents and in the Council of the European Union Policy Documents. In the Presidency Program, for example, it is mentioned that “many

refugees and third country nationals, who wish to go back to their former regions out of free will, find

themselves hindered by formal non-existent but in practice impregnable borders. Despite these

hardships we have to implement the Dayton Agreement in a strict manner” (Tweede Kamer der

Staten Generaal 1996, 15). It mainly is about refugees and migrants going back out of free will. There is no explicit mentioning of forced eviction of migrants.

The Dutch Government argues that in light of the Schengen Agreement and the implementation of the

Dayton Agreement that the cooperation needs to be continued intensely, especially in the area of the

“migration risk” (...) (Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal 1996, 56). This is a clear example of

migration being framed as a public security issue in the Dutch Presidency Programme document.

35 While some migrants are denied legal access, they are forced to use false documents because they lost their old documents, but still need to cross borders (Hayter 2001, 153). The

document also shows the importance for the Dutch government of the readmission of refugees out of free will to the former Yugoslavia.

Table 6.2 Council of the European Union policy documents Frame

Document

Public Security Frame

Us vs. Them Frame

Numbers Frame Genuine Refugee vs. Illegal Immigrant No Clear Framing or Other Frames Council Regulation July ‘96 X Council Decision December ‘96 X Council Decision May ‘97 X Council Activity Report ‘94/’95 (CIREA) May ‘97

X x

Council Activity Report ’96 (CIREA) May ‘97 x Council Conclusions Dublin Convention May ‘97 x Council Resolution June ‘97 x Council Decision June ‘97 X Council Joint Action July ‘97

x

Council Resolution December ‘97

36 Table 6.2 shows that the frame most frequently applied by the Council of the European Union, was the genuine or legal migrant versus the illegal migrant frame. Some examples of this frame are for example reflected in the Council Resolution of 26 June 1997, 1) “to combat

unauthorized immigration and residence by nationals of third countries on the territory of Member

States”. 2) “Whereas the unauthorized presence in the territory of Member States of unaccompanied

minors who are not regarded as refugees must be temporary, with Member States” (Council of

European Union 1997, 1). By using words like “combat”, “unauthorized” the Council invokes images of illegality and therefore criminal behavior of migrants, in this case of unaccompanied minors. The unaccompanied minors, or just simply put, children, are referred to as being criminals because they are “unauthorized” to be in a certain area. In one document the numbers frame was used as well. This was in a CIREA report which is the Centre for Information, Discussion and Exchange on Asylum. It stated that extra focus was needed for policy and information gathering on regions where “the largest number of

asylum-seekers in Member States” originate from (Council of the European Union 1997, 3). This

was necessary according to the document to find the sources of these ‘large numbers’ of refugees. By referring to large numbers instead of refugees or migrants in general it becomes possible to implement the policies the Council deems necessary.

37

6.2 Dutch EU Presidency of 2004

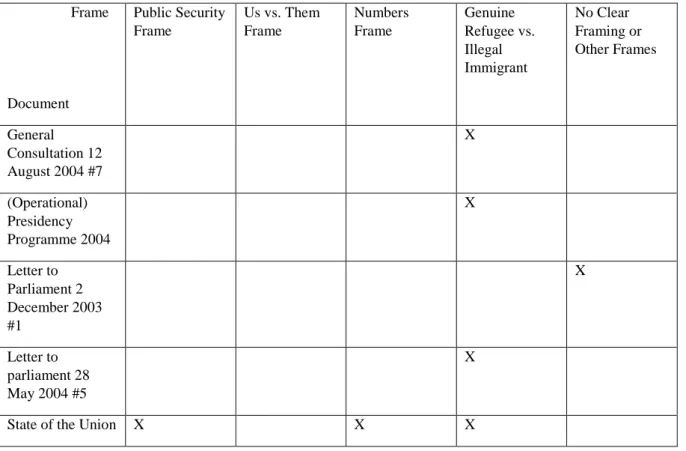

Table 6.3 Dutch Governmental documents Frame

Document

Public Security Frame

Us vs. Them Frame Numbers Frame Genuine Refugee vs. Illegal Immigrant No Clear Framing or Other Frames General Consultation 12 August 2004 #7

X (Operational) Presidency Programme 2004 X Letter to Parliament 2 December 2003 #1 X Letter to parliament 28 May 2004 #5

X

State of the Union X X X

In 2004 the Dutch government used several different frames in their policy documents on the EU Presidency and in their correspondence with the Dutch parliament. In the General

Consultation of 12 Augustus 2004 the Minister of Immigration and Integration Rita Verdonk used the genuine vs. illegal immigrant frame several times. She argued that it was necessary to send illegal migrants back as soon as possible. Furthermore, she wishes to implement

“biometric applications. Because they are extremely important for the combat of illegal migration and

terrorism”. These words connect (illegal) migration indirectly to terrorism, as if they were

connected or interrelated. It criminalizes migrants that do not comply with the “official qualifications” (Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal 2004, 8-9). There seems to be a strong focus on sending people back during this Presidency as well. However, this time the words out of “free will” are omitted.

38

human beings will be an important priority in 2004 (…) of a common asylum and migration policy,

building on the legislative programme on minimum norms originating from the Amsterdam Treaty”

(Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal 2003, 31). The EU wishes to combat illegal immigration and build a common asylum and migration policy. By building on the minimum norms of the definition of legal migration and refugees laid down in the Amsterdam Treaty. By building on these norms the EU decides who is a legal migrant and how is regarded as unwanted and illegal.

On the 28 of May the Dutch Government wrote a Letter to Parliament. In this letter they used the genuine refugee vs. illegal immigrant frame to justify their aims for sending migrants back. By declaring some migrants illegal while others are genuine refugees they make a clear distinction, for the audience, to be able to implement policies to decrease the numbers of migrants to the EU. This is reflected in the next quote: “The Development of a European return

policy is for the Netherlands an integral part of the fight against illegal immigration. It is both a

concluding piece and a preventive measure by the signal it gives [to (illegal) migrants]” (Tweede

Kamer der Staten Generaal 2004, 18).

In the State of the Union of 2004 there were several frames used. For example, the public security frame and the numbers frame in the same paragraph. The Dutch government argued that “in the combat against terrorism, the Union needs to cooperate internationally. Safe

borders help to achieve this, because international migration flows, as a consequence of conflicts or

economic considerations, still demand attention” (Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal 2004, 18).

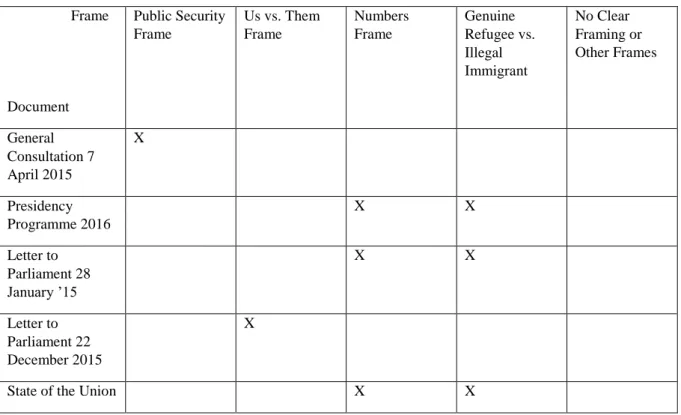

39 Table 6.4 Council of the European Union policy documents

Frame

Document

Public Security Frame

Us vs. Them Frame Numbers Frame Genuine Refugee vs. Illegal Immigrant No Clear Framing or Other Frames Council Regulation February 2004

X X

Council Decision February 2004

X X

Council

Regulation March 2004

X X

Council Decision April 2004 X Council Directive April 2004 X Council Directive April 2004 X Council Decision December 2004 X Council Regulation December 2004 X Council Decision December 2004 X Council Decision December 2004 X Council: The Hague Programme March 2005

X X