0095-1137/00/$04.00⫹0

Copyright © 2000, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved.

Sequence Analysis and Clinical Significance of the

iceA

Gene

from

Helicobacter pylori

Strains in Japan

YOSHIYUKI ITO,1TAKESHI AZUMA,1* SHIGEJI ITO,1HIROYUKI SUTO,1HIDEKI MIYAJI,1

YUKINAO YAMAZAKI,1TAKUJI KATO,2YOSHIHIRO KOHLI,3YOSHIHIDE KEIDA,4 ANDMASARU KURIYAMA1

Second Department of Internal Medicine, Fukui Medical University,1and Fukui Prefectural University, College of Nursing,2Fukui, Division of Internal Medicine, Aiseikai Yamashina Hospital, Kyoto,3and Division of Internal

Medicine, Okinawa Chubu Hospital, Okinawa,4Japan

Received 7 June 1999/Returned for modification 17 August 1999/Accepted 1 November 1999

TheHelicobacter pylori iceAgene was recently identified as a genetic marker for the development of peptic

ulcer in a Western population. To assess the significance oficeAsubtypes ofH. pyloriin relation to peptic ulcer,

140 Japanese clinical isolates (88 from Fukui and 52 from Okinawa) were characterized. Sequence analysis of theiceA1gene from 25 representative Japanese strains was also carried out to identify the differences iniceA

between the ulcer group and the gastritis group. TheiceA1genotype was not correlated with the presence of

peptic ulceration in either area. In addition, sequence analysis led to identification of five deletions and five

point mutations (a nonsense mutation or a 1-bp insertion) within theiceA1open reading frame corresponding

to previously published sequences. These mutations were identified in both clinical groups (ulcer and gastritis groups) in each area. Local DNA sequence analysis revealed that the endpoints of all five deletions coincided

with direct repeats. We also found four strains that carried longericeA1open reading frames compared with

that for strain 60190. In conclusion, carriage of aniceA1strain does not seem to be a risk factor for peptic ulcer

in Japanese subjects. The critical mutations in theiceA1gene in some isolates from patients with peptic ulcers

suggested that IceA does not participate in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer in Japan. We also found deletion

hot spots that were associated with direct repeats iniceA1and that favored a small-deletion model of slipped

mispairing events during replication. We showed that iceA1 sequence variations may be useful tools for

analysis of the population genetics ofH. pylori.

Helicobacter pyloriinfection is now recognized as a signifi-cant risk factor for both gastric and duodenal ulcers, gastric adenocarcinoma, and MALT lymphoma (11, 16, 17, 20). How-ever, only a minority of infected patients develop such severe diseases, and most infected individuals are asymptomatic throughout life. Such variations in clinical outcome may be due to the considerable genetic diversity of theH. pyloristrains that cause infection, although host factors may also be important for the development of disease.

Strains that possess two virulence factors, vacuolating cyto-toxin encoded byvacAand a 40-kb DNA segment named the cagpathogenicity island (4), are associated with severe diseases in the West (3, 6, 7, 9, 21–23). ThevacAgenotype (3) and the presence ofcagA (which is at one end of cag pathogenicity island) are mainly used as simple genetic markers for these virulence traits. However, close associations between these vir-ulence factors and clinical presentation have not been con-firmed in East Asian populations, and most isolates in this region werecagApositive and of thevacAs1 type, regardless of clinical manifestations (12, 13, 15, 26). Some sequence studies have shown that these two virulence-associated genes (cagA and vacA) are distinct between strains from East Asia and Europe (12, 25). Recent studies of the population genetics of H. pylori strains from diverse geographic locations demon-strated that Asian strains were assigned to the same “Asian” clonal group, probably reflecting descent from distinct com-mon ancestors, andcagAandvacAare more diverse than other

housekeeping genes among strains (1). Therefore, different combinations of bacterial and/or human factors may be critical determinants of disease in East Asian population. Moreover, sequence analysis of virulence genes may provide useful mak-ers for study of the population genetics ofH. pylori.

Recently, Peek et al. (18) reported on a novelH. pylorigene, iceA(induced by contact with epithelium). There are two dif-ferent alleles of this gene (iceA1 and iceA2), and iceA1 is replaced byiceA2at the same locus in many strains.iceA2is a gene that is completely unrelated to iceA1 or other known proteins. Although iceA1 encodes a homolog of a putative restriction endonuclease (nlaIIIR) ofNeisseria lactamica(14), the role of the iceA gene product during human infection remains unknown and the translational start site oficeA1has not yet been confirmed (23). Interestingly, carriage of iceA1 was shown to be weakly but significantly associated with peptic ulcer in studies ofH. pyloristrains from Europe (Holland) and the United States (18, 23).

In the study described here, we assessed the linkage between iceAgenotype and peptic ulcer in two different areas of Japan. Moreover, we sequenced and analyzed the full-length iceA gene from isolates obtained from patients with peptic ulcer or chronic gastritis and also examined whether there are different sequence motifs or segments that can be used to distinguish between Japanese and Western strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.Two different areas of Japan were selected as sources of strains for

iceAanalysis. Fukui is a typical rural prefecture located in the central Japanese mainland (Honshu), while Okinawa consists of islands in the southwestern part of Japan and has a history and food culture different from those for other parts of Japan. Clinical isolates ofH. pyloriwere obtained from 140 Japanese patients (88 patients from Fukui and 52 patients from Okinawa) during gastroduodenal * Corresponding author. Mailing address: Second Department of

Internal Medicine, Fukui Medical University, Matsuoka-cho, Yoshida-gun, Fukui 910-1193, Japan. Phone: 81-776-61-3111, ext. 2300. Fax: 81-776-61-8110. E-mail: azuma@fmsrsa.fukui-med.ac.jp.

483

on May 15, 2020 by guest

http://jcm.asm.org/

endoscopy at the Second Department of Internal Medicine, Fukui Medical University, Fukui, and Division of Internal Medicine, Okinawa Chubu Hospital, Okinawa, respectively. The 88 patients in Fukui consisted of 49 with peptic ulcer (mean age, 53.7 years) and 39 with chronic gastritis (mean age, 58.3 years). The 52 Okinawan patients consisted of 19 with peptic ulcer (mean age, 58.3 years) and 33 with chronic gastritis (mean age, 59.6 years). Patients underwent endos-copy because of upper abdominal complaints or as part of an annual health check. Ulcer was defined as sharply delineated mucosal defects of at least 5 mm in one dimension, with depth. Patients with ulcer scars showing retraction with converging folds at endoscopy and the presence of past medical or endoscopic records of ulcer were included in the ulcer group. Patients who had received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or antacids were excluded from this study, and none of the patients had recently been prescribed antibiotics.

Isolation and culture ofH. pylori.Two gastric biopsy specimens were

sequen-tially taken from the gastric body and antrum with a sterilized endoscope. Biopsy samples were immediately put into Cary-Blair-N transport medium (Nissui Seiy-aku Co., Tokyo, Japan) and were cultured on Trypticase Soy Agar-II plates containing 5% sheep blood (Nippon Becton Dickinson, Tokyo, Japan) for 5 days at 37°C under microaerobic conditions (5% O2, 15% CO2, 80% N2). The

spec-imens obtained from Okinawan patients were sent by air in the same transport medium in an icebox and were cultured within 24 h after biopsy. A single colony from each patient was picked from the culture plate and was inoculated onto another fresh culture plate. A few colonies from the second culture plate were inoculated into 20 ml of brucella broth containing 10% fetal calf serum and were cultured for 3 days under the same conditions described above.H. pyloricells were harvested from the bacterial suspensions by centrifugation at 1,300⫻gfor 10 min. Chromosomal DNA was extracted from the pellets by the protease and phenol-chloroform method, suspended in 300l of TE buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, 1 mM EDTA), and stored at 4°C until PCR amplification. The type strains NCTC 11916 and NCTC 11637 were also analyzed for theiriceAgenotypes.

Typing oficeAgene.On the basis of information from a previous study (25),

two primer sets, iceA1F (5⬘-GTGTTTTTAACCAAAGTATC-3⬘) and iceA1R (5⬘-CTATAGCCASTYTCTTTGCA-3⬘) foriceA1and iceA2F GTTGGGTATA TCACAATTTAT 3⬘) and iceA2R (5⬘-TTRCCCTATTTTCTAGTAGGT-3⬘) for iceA2, were used to determine theiceAgenotype (23). PCR was performed in 50-l reaction mixtures containing 1l of genomic DNA (50 to 100 ng), 250 nM (each) primer, 1⫻reaction buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 U of AmpliTaq DNA

polymerase, and distilled, sterilized water in a GeneAmp 2400 PCR system (Perkin-Elmer Japan, Chiba, Japan). After boiling at 94°C for 5 min, amplifica-tion was carried out for 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The mixture was then held at 72°C for 7 min to complete the elongation step and was finally stored at 4°C. PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and were examined under UV illumination.

cagAstatus andvacAgenotype were determined previously by PCR-based typing or DNA sequencing forvacAand by hybridization forcagA, respectively (12; Y. Ito, T. Azuma, S. Ito, H. Suto, H. Miyaji, Y. Yamazaki, M. Kuriyama, Y. Kohli, and Y. Keida, Gastroenterology 116, abstr. A196, 1999).

DNA sequencing of entireiceAgene.Fourteen isolates from Fukui (7 from

patients with peptic ulcer and 7 from patients with chronic gastritis only) and 11 isolates from Okinawa (5 from patients with peptic ulcer and 6 from patients with chronic gastritis only) were randomly selected for sequence analysis oficeA1. The region comprising the entireiceAregion of each isolate was amplified with the iceA-spanning primer set IAS-F and IAS-R (Table 1). PCR conditions were as follows: heating at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The tubes were held at 72°C for 7 min,

before storage at 4°C. The PCR products were then purified with Centricon-100 Concentrator columns (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.). DNA sequencing was per-formed by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method with a BigDye Ter-minator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Mix (Perkin-Elmer Japan) in an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin-Elmer Japan). According to the manu-facturer’s protocol, reagent mixtures containing 5l of purified PCR product, 3.2 pmol of primer, 8l of Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Mix, and 5l of sterilized distilled water were prepared. Reaction tubes were placed in the thermal cycler, and thermal cycling was started under the following conditions: 96°C for 10 s, 50°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 4 min, which was repeated for 25 cycles. Cycle sequencing reactions were performed for both DNA strands. Nucleotide sequences were aligned and analyzed with GENTYX-MAC, version 8.0 (Soft-ware Development Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Statistics.The association betweeniceAgenotype and clinical outcome in both

areas were analyzed by Fisher’s exact probability test. APvalue of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.The DNA sequences of theiceA1

genes of each strain characterized here were deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. AF157527 to AF157551).

RESULTS

Typing oficeA.A total of 140 Japanese isolates and 2 type

[image:2.612.54.552.83.232.2]strains (strains NCTC 11916 and NCTC 11637) were investi-gated for determination of theiriceAgenotypes. The distribu-tions of iceA genotypes in two areas of Japan (Fukui and Okinawa) are shown in Table 2. One hundred thirty-six Japa-nese isolates (97.1%) could be typed by this PCR-based method, and no isolates containing bothiceA1andiceA2were found. For four Fukui strains, no PCR products were obtained with the allele-specific primers. DNA sequencing of full-length iceA determined the genotypes of these untypeable strains. Although these isolates were of the iceA1 type, deletion of TABLE 1. Primers used for sequence analysis oficeA

Procedure and primer

(direction) Nucleotide sequencea Position

iceA1sequencing

IAS-F (⫹) 5⬘-CGTGGGCGATGATGTGAAGATTG-3⬘ 426–446b

IAS-R (⫺) 5⬘-CGTCCCAGCGAACAGATCACAA-3⬘ 1403–1424b

IAS-2F (⫹) 5⬘-GGCAACTCTGAAAACACTC-3⬘ 934–952b

IAS-2R (⫹) 5⬘-TCCTGTATTGTATGGGGTC-3⬘ 1192–1210b

Mutation screening

iceA11033C/T (⫹) 5⬘-CAGACTCTTGATGATTTCT-3⬘ 489–511c

IAS-R (⫺) 5⬘-CGTCCCAGCGAACAGATCACAA-3⬘ 1403–1424b

1172 del5 (⫹) 5⬘-TGAATATGACGGTTGCT-3⬘ 661–677d

IAS-R (⫺) 5⬘-CGTCCCAGCGAACAGATCACAA-3⬘ 1403–1424b

aR is G or A, Y is C or T, and S is G or C.

bCorresponding to strain 60190 (GenBank accession no. U43917). cCorresponding to strain F79 (GenBank accession no. AF157537). dCorresponding to strain OK104 (GenBank accession no. AF157541).

TABLE 2. Distribution oficeAgenotype in each area (Fukui and Okinawa)

Genotype

No. (%) of strains

Fukuia Okinawab

Peptic ulcer Chronic gastritis Peptic ulcer Chronic gastritis

iceA1 33 (67.3) 26 (66.7) 15 (78.9) 25 (75.8)

iceA2 16 (32.7) 13 (33.3) 4 (21.1) 8 (24.2)

Total 49 39 19 33

aP⫽0.617. bP⫽0.538.

on May 15, 2020 by guest

http://jcm.asm.org/

[image:2.612.312.551.623.712.2]nucleotides corresponding to the iceA1F primer region pre-vented typing (data not shown).

On amplification of iceA1, the sizes of the PCR products were slightly different among isolates, suggesting the existence of a deletion in this region. van Doorn et al. (23) reported that there are twoiceA2type strains; one showed an amplicon of 229 bp with theiceA2-specific primer set, and the other yielded a 334-bp amplicon containing a 105-bp in-frame duplication. All JapaneseiceA2type strains yielded an amplicon of 229 bp. In contrast, NCTC 11916 and NCTC 11637 were found to contain aniceA2gene yielding a 334-bp amplicon. As shown in Table 2, there was no significant association between iceA genotype and peptic ulcer disease in each area (Fukui,P⫽

0.617; Okinawa, P ⫽ 0.538). Isolates possessing iceA1 were found more frequently in Okinawa (76.9%) than in Fukui (67.0%), but the difference was not significant (P⫽0.147). As shown in our previous study, all of the Japanese strains in this study werecagApositive. Moreover, almost all Fukui strains and more than 80% of Okinawan strains were of the s1/m1 vacA type. No significant associations were found between these two virulence-associated gene subtypes and theiceA ge-notype.

Sequence analysis of iceA1. Primer set IAS-F and IAS-R

successfully amplified the entireiceA1regions of all 25 strains. The sequence data for the iceA1 genes from 25 Japanese strains and 5 Western strains deposited in the GenBank data-base are summarized in Table 3. Alignment of theiceA1gene between Japanese strains and 60190 (GenBank accession no. U43917) revealed that theiceA1gene in many Japanese strains contained in-frame deletions compared with that of strain 60190. We found small deletions of six nucleotides, TAATTT at nucleotide 780, AATTTG at nucleotide 781, or TTTGGA at nucleotide 783, of theiceAopen reading frame of strain 60190. These three deletions were considered to be caused by same deletion mechanism (at the same direct repeats), and the de-letion of six nucleotides at nucleotide 780 (780del6) was found more frequently than the other deletions. Therefore, these three deletions are arbitrarily designated 780del6. Another deletion of 24 nucleotides at nucleotide 1246 was designated 1246del24. Three deletions, a five-nucleotide deletion at nu-cleotide 809 (809del5), a seven-nunu-cleotide deletion at nucleo-tide 914 (914del7), and a five-nucleonucleo-tide deletion at nucleonucleo-tide 1172 (1172del5), caused frameshifts that resulted in early translational termination of iceA1. These in-frame deletions were frequently identified among Japanese strains (Tables 3 and 4). For example, 809del5 was found in 14 (56.0%) of 25 Japanese isolates and 914del7 was identified in 11 isolates (44.0%). Furthermore, three different deletions (780del6, 809del5, and 914del7) were simultaneously observed in nine Japanese isolates. The local DNA sequences surrounding these five deletions revealed that these deletion endpoints coincided with direct repeats of between 5 and 10 nucleotides (Table 4). In addition to deletions, five different point mutations that caused early translational termination oficeA1were identified in seven strains (Table 3). Due to combinations of these mu-tations (frameshift and point mumu-tations), the length of the predicted iceA1 open reading frame was different among strains (range, 117 to 696 bp). Of interest, 4 Japanese strains (strains F38, F72, OK108 and F43) possessed a longericeA1 open reading frame (684 or 696 bp) than that of strain 60190 (534 bp). A putative ribosomal binding site (AGGA) was iden-tified 8 bp upstream of the ATG translational initiation codon. The lengths of the predicted amino acid sequences of iceA1 from these four Japanese isolates were similar to that of NlaIIIR ofN. lactamica(228 or 232 versus 230 amino acids). The amino acid identities of the iceA1 open reading frames

from these four isolates (isolates F38, F72, OK108, and F43) and NlaIIIR were 56.2, 53.4, 57.1, and 53.4%, respectively.

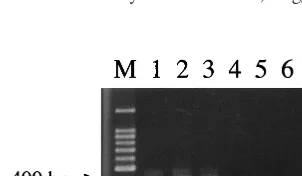

Detection of specific mutation oficeA1gene.Strains with two

mutations, 1033C/T (C-to-T nonsense mutation at nucleotide 1033) and 1072del5, were selected for further analysis because carriage of these mutations causes early translational termina-tion oficeA1. We screened 99 Japanese isolates with theiceA1 genotype for these mutations by PCR amplification using the specific primer sets listed in Table 1. We evaluated the perfor-mances of these two primer sets for detection of each mutation by using 25 strains that were sequenced as described above and confirmed the usefulness of these primer sets (Fig. 1). A non-sense mutation (1033C/T) was identified in 5 (8.5%) of 59 iceA1 type strains from Fukui, while this mutation was not found in any of 40 Okinawan strains examined. In contrast, 1072del5 was identified in 7 (17.5%) of 40 OkinawaniceA1 strains but in none of 59 Fukui strains.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that there were no significant dif-ferences in the proportions of strains with theiceA1genotype between peptic ulcer and chronic ulcer groups. We also showed that theiceA1genotype did not appear to be a reliable marker of peptic ulcer disease among Japanese subjects in two areas separated by more than 1,300 km. Our data were incon-sistent with those of recent reports in the West (18, 23) sug-gesting a significant association betweeniceA1genotype and peptic ulcer. It is possible that asymptomatic patients infected withiceA1type strains develop peptic ulcer disease later in life. However, this is unlikely because the difference in mean age among the two clinical groups was not significant. We also could not exclude the possibility that patients with peptic ulcer may be simultaneously infected withiceA1 and iceA2 strains because we used a single representative strain to assess the iceAgenotype in each patient. However, concurrent infection with more than two different strains assessed by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting in Japanese pa-tients (Fukui) occurs at a frequency of only about 5% (unpub-lished data). In addition, iceA1 type strains were more fre-quently found in Okinawa (76.9%) than in Fukui (67.0%), although the number of patients with peptic ulcers in the Okinawan group (36.5%) was smaller than the number in the Fukui group (55.7%). Therefore, our results could not support previous studies in whichiceA1type strains were shown to have a virulence potential.

Sequence analysis of theiceA1genes from 25 strains was also carried out to obtain new insight into the genetic differences between the peptic ulcer group and the gastritis group. Inter-estingly, we found five deletions within theiceA1open reading frame of Japanese strains compared with previously published sequences, and these deletions were frequently identified in Japanese isolates, suggesting deletion hot spots iniceA1. It is well known that local DNA sequences containing repeat se-quences (direct repeats or inverted repeats) may cause dele-tion by misalignment during DNA replicadele-tion or recombina-tion (8, 19). In this study, we found that delerecombina-tion endpoints coincided with direct repeats. Therefore, these direct repeats may be responsible for each deletion identified within the iceA1 genes of Japanese strains. However, we found three deletions simultaneously among Japanese isolates. Moreover, Japanese strains have highly homologousvacAandcagAgenes (12). Therefore, a founder effect may also participate in the high prevalence of in-frame deletions in Japanese strains as well as mutational hot spots.

In this study, we also found five different point mutations

on May 15, 2020 by guest

http://jcm.asm.org/

that caused premature termination oficeA1 translation. Re-cently, we reported that variousvacAmutations are responsi-ble for a deficiency of cytotoxin activity among Japanese strains (13). Therefore, it is likely that iceA1containing such muta-tions has no function, although we could not exclude the pos-sibility that the truncated protein remains functional. Recent

[image:4.612.54.552.82.598.2]reports suggested that point mutations in specific H. pylori genes were shown to be associated with disease (5) or antibi-otic resistance (10, 24). Therefore, we expected that truncating mutations oficeA1occurred only in strains from patients with gastritis. However, these truncating mutations were identified iniceA1genes from not only the gastritis group but also the TABLE 3. Sequence analysis oficeA1gene fromH. pyloristrains in Japana

Location, disease, and

strain cagA vacA Cytotoxinactivityf iceA(bp)ORFc

In-frame deletionb

Point mutation 780del6 809del5 914del7 1172del5 1246del24

Fukui CG (n⫽7)

F13 ⫹ s1/m1 384 ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

F15 ⫹ s1/m1 1 384 ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

F16 ⫹ s1/m1 2 117 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫹ 1033C/T

F36 ⫹ s1/m1 2 534 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

F37 ⫹ s1/m1 1 519 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

F38 ⫹ s1/m1 6 684 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

F43 ⫹ s1/m1 7 696 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

PUD (n⫽7)

F70 ⫹ s1/m1 0 360 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫹

F72 ⫹ s1/m1 4 684 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

F73 ⫹ s1/m1 3 384 ⫺ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫺

F79 ⫹ s1/m1 7 117 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫹ 1033C/T

F82 ⫹ s1/m1 4 360 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫹

F83 ⫹ s1/m1 5 360 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫹

F84 ⫹ s1/m1 7 117 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫹ 1033C/T

Total no. pos/total no. 8/14 9/14 7/14 0/14 6/14

Okinawa CG (n⫽6)

OK104 ⫹ s1/m1 1 267 ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫹ ⫺

OK106 ⫹ s1/m1 1 384 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫺ 1059insT, 1090insA

OK107 ⫹ s1/m2 0 141 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫹ ⫺ 1059insT

OK111 ⫹ s1/m1 2 141 ⫹ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

OK115 ⫹ s1/m1 2 510 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫹ 786G/A

OK129 ⫹ s1/m2 0 357 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫹

PUD (n⫽5)

OK99 ⫹ s1/m1 4 384 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫺

OK102 ⫹ s1/m1 2 384 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫺

OK108 ⫹ s1/m1 0 684 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

OK113 ⫹ s1/m1 0 357 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫹ 904C/T

OK134 ⫹ s1/m1 1 384 ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ ⫺ ⫺

Total no. pos/total no. 6/11 5/11 4/11 2/11 2/11

Alaskad

209 Unknown Unknown Unknown 684 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

214 Unknown Unknown Unknown 459 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ 1059delT

218 Unknown Unknown Unknown 660 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫹

Total no. pos/total no. 0/3 0/3 0/3 0/3 1/3

United Kingdom

60190 ⫹ s1/m1 Pos 584 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

26695e ⫹ s1/m1 Pos 516 ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺ ⫺

Total 0/2 0/2 0/2 0/2 0/2

aAbbreviations: ORF, open reading frame; CG, chronic gastritis; PUD, peptic ulcer disease; del, deletion; ins, insertion; pos, positive. b⫹, presence of deletion;⫺, absence of deletion.

cNucleotide corresponding to published sequence ofH. pylori60190 including theiceAopen reading frame and upstream sequence (GenBank accession no. U43917). dAccession no. AF001537-9.

eAccession no. AE000626.

fThe relative activity of vacuolating cytotoxin was defined as the index number at the maximum dilution, as described previously (12).

on May 15, 2020 by guest

http://jcm.asm.org/

peptic ulcer group, and the shortest open reading frame (117 bp) iniceA1was identified in isolates from both clinical groups. These results suggested that theiceA1gene product does not contribute critically to the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease in the Japanese population.

In this study, we found four Japanese isolates that possess an iceAopen reading frame longer than that of strain 60190. The predicted amino acid sequences oficeA1gene products from these four isolates were similar to that of the NlaIIIR protein. Further studies should be carried out to determine whether 228- or 232-amino-acid IceA1 proteins are functional and the truncated IceA1 is not. Recently, Raudonikiene and Berg (A. Raudonikiene and D. E. Berg, GenBank accession nos. AF001537 to AF001539) reported on threeiceA1-type Alaska strains with a different translational start point from that of strain 60190, as shown in this study, and two of these three strains contained mutations, 1246del24 and 1059insT, respec-tively.

We also showed geographical variation iniceA1mutations. Four deletions (780del6, 809del5, 914del7, and 1246del24) were distributed uniformly in both areas, suggesting a very

early origin. In contrast, a nonsense mutation at nucleotide 1033 (1033C/T) was identified only among the Fukui strains, while 5-bp deletion at nucleotides 1172 to 1176 (1172del5) was found only among Okinawan strains. Therefore, the profile of iceA1mutations may represent the nature ofH. pylorilineages. Most otherH. pylorigenes studied to date were highly poly-morphic only for point mutations and not for insertion or deletion differences. This study indicated that various alleles of iceA1may be very useful as indicators of evolutionary diver-gence inH. pylorigene pools from different regions, for the tracing of strain types, and for the differentiation of single versus multiple infections.

In conclusion, we could not confirm the significance oficeA genotyping as a predictor of peptic ulcer disease, and we found that many Japanese isolates contained iceA1 mutations, re-gardless of the clinical outcome. These results indicated that theiceAgenotype is not a useful marker of virulence in this population and that the progression from gastritis to peptic ulcer must require some other genes or factors including the genetic susceptibility of the host. However, we showed that iceA1 sequence variations may provide useful markers that indicate the divergence ofH. pyloristrains from different geo-graphic regions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Douglas E. Berg for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable comments, Manabu Inuzuka for stimulating discussion, and Syuko Murayama and Akiyo Yamakawa for technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (grant 11670555) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

1.Achtman, M., T. Azuma, D. E. Berg, Y. Ito, G. Morelli, Z.-J. Pan, S.

Suer-baum, S. A. Thompson, A. van der Ende, and L.-J. van Doorn.1999.

[image:5.612.55.547.84.321.2]Re-combination and clonal groupings withinHelicobacter pylorifrom different FIG. 1. Detection of 1033C/T nonsense mutation by PCR. Lanes 1 to 3,

[image:5.612.97.248.605.693.2]strains carrying the 1033C/T mutation (strains F16, F79 and F84, respectively); lanes 4 to 7, strains without 1033C/T (strains F13, F15, F82, and F83, respec-tively); lane M, size marker (100-bp ladder).

TABLE 4. Local DNA sequences surrounding deletions iniceA1gene

Deletion Strainb Sequencea Repeated element No. of isolates positive/

total no. of isolates (%)

780del6 60190 AGAATTTAATTTGGAGTTT AGAATTT or AATTT 14/25 (56.0)

F38 AGAATTTGAATTAGAATTT F82 AGAATT AGAATTT

809del5 60190 AAACTCTAGGAAATTCTA AAAYTCTA 14/25 (56.0)

F38 AAACTCTAGGAAATTCTA F82 AAACTC AATTCTA

914del7 60190 GTGTGGTGTGCGTGGC GTGCG or GTGTGS 11/25 (44.0)

F38 GTGCGGTGTGCGTGGC F82 GTGCG TGGC

1172del5 60190 GGTTGTGTGGGCTGTTAT GGTTGT 2/25 (8.0)

F38 GGTTGTGTGGGTTGTTAT

OK104 GGTTGC TTGTTAT

1246del24 60190 GGGTATCAAAAAGGCTATG GGGTATCAAA 9/25 (36.0)

F38 GGGTATCAAAAAGGTTATT F82 GGGTATCAAA

1246del24 60190 GTGATGGGTATCAAATTGG

F38 ATGAGGGGTATCAAATTGG

F82 TTGG

aNucleotides corresponding to theiceAopen reading frame and its upstream sequence of strain 60190 (GenBank accession no. U43917). del, deletion. bStrains 60190 and F38 are representative Western and Japanese strains, respectively. F82 and OK104 are representative strains carrying each mutation. Underlined nucleotides indicate direct repeats (overlapping in 914del7). Y is T or C, and S is G or C.

on May 15, 2020 by guest

http://jcm.asm.org/

geographical regions. Mol. Microbiol.32:459–470.

2.Akopyants, N. S., S. W. Clifton, D. Kersulyte, J. E. Crabtree, B. E. Youree,

C. A. Reece, N. O. Bukanov, E. S. Drazek, B. A. Roe, and D. E. Berg.1998.

Analysis of thecagpathogenicity island ofHelicobacter pylori. Mol. Micro-biol.28:37–53.

3.Atherton, J. C., P. Cao, R. M. Peek, M. K. R. Tummuru, M. J. Blaser, and

T. L. Cover.1995. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles ofHelicobacter

pylori. J. Biol. Chem.270:17771–17777.

4.Censini, S., C. Lange, Z. Xiang, J. E. Crabtree, P. Ghiara, M. Borodovsky,

R. Rappuoli, and A. Covacci.1996.cag, a pathogenicity island ofHelicobacter

pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA93:14648–14653.

5.Chang, C.-S., L.-T. Chen, J.-C. Yang, J.-T. Lin, K.-C. Chang, and J.-T. Wang.

1999. Isolation of aHelicobacter pyloriprotein, FldA, associated with muco-sa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach. Gastroenterology

117:82–88.

6.Cover, T. L., C. P. Dooley, and M. J. Blaser.1990. Characterization of and

human serologic response to proteins inHelicobacter pyloribroth culture supernatants with vacuolizing cytotoxin activity. Infect. Immun.58:603–610.

7.Crabtree, J. E., J. D. Taylor, J. I. Wyatt, R. V. Heatley, T. M. Shallcross, D. S.

Tompkins, and B. J. Rathbone.1991. Mucosal IgA recognition of

Helico-bacter pylori120 kDa protein, peptic ulceration, and gastric pathology. Lan-cet338:332–335.

8.Farabaugh, P. J., U. Schmeissner, M. Hofer, and J. H. Miller.1978. Genetic

studies on thelacrepressor. VII. On the molecular nature of spontaneous hotspots in thelacIgene ofEscherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol.126:847–863.

9.Figura, N., P. Guglielmetti, A. Rossolini, A. Barberi, G. Cusi, R. A.

Musm-anno, M. Russi, and S. Quaranta.1989. Cytotoxin production by

Campy-lobacter pyloristrains isolated from patients with peptic ulcers and from patients with chronic gastritis only. J. Clin. Microbiol.27:225–226.

10. Goodwin, A., D. Kersulyte, G. Sisson, S. J. O. V. van Zanten, D. E. Berg, and

P. S. Hoffman.1998. Metronidazole resistance inHelicobacter pyloriis due to

null mutations in a gene (rdxA) that encodes an oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitroreductase. Mol. Microbiol.28:383–393.

11. Hentschel, E., G. Brandstatter, B. Dragosics, A. M. Hirschl, H. Nemec, K.

Schutze, M. Taufer, and H. Wurzer.1993. Effect of ranitidine and amoxicillin

plus metronidazole on the eradication ofHelicobacter pyloriand the recur-rence of duodenal ulcer. N. Engl. J. Med.328:308–312.

12. Ito, Y., T. Azuma, S. Ito, H. Miyaji, M. Hirai, Y. Yamazaki, F. Sato, T. Kato,

Y. Kohli, and M. Kuriyama.1997. Analysis and typing of thevacAgene from

cagA-positive strains ofHelicobacter pyloriisolated in Japan. J. Clin. Micro-biol.35:1710–1714.

13. Ito, Y., T. Azuma, S. Ito, H. Suto, H. Miyaji, Y. Yamazaki, Y. Kohli, and M.

Kuriyama.1998. Full-length sequence analysis of thevacAgene from

cyto-toxic and noncytocyto-toxicHelicobacter pylori. J. Infect. Dis.178:1391–1398.

14. Morgan, R. D., R. R. Camp, G. G. Wilson, and S.-Y. Xu.1996. Molecular

cloning and expression ofNlaIII restriction-modification system inE. coli. Gene183:215–218.

15. Pan, Z. J., D. E. Berg, R. W. M. van der Hulst, W.-W. Su, A. Raudonikiene,

S.-D. Xiao, J. Dankert, G. N. J. Tytgat, and A. van der Ende.1998.

Preva-lence of vacuolating cytotoxin production and distribution of distinctvacA alleles inHelicobacter pylorifrom China. J. Infect. Dis.178:220–226.

16. Parsonnet, J., G. D. Friedman, D. P. Vandersteen, Y. Chang, J. H. Vogelman,

N. Orentreich, and R. K. Sibley.1991.Helicobacter pyloriinfection and the

risk of gastric carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med.325:1127–1131.

17. Parsonnet, J., S. Hansen, L. Rodriguez, A. B. Gelb, R. A. Warnke, E. Jellum,

N. Orentreich, J. H. Vogelman, and G. D. Friedman.1994.Helicobacter pylori

infection and gastric lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med.330:1267–1271.

18. Peek, R. M., S. A. Thompson, J. P. Donahue, K. T. Tham, J. C. Atherton,

M. J. Blaser, and G. G. Miller.1998. Adherence to gastric epithelial cells

induces expression of aHelicobacter pylorigene,iceA, that is associated with clinical outcome. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians110:531–544.

19. Ripley, L. S.1990. Frameshift mutation: determinants of specificity. Annu.

Rev. Genet.24:189–213.

20. Sung, J. J. Y., S. C. Chung, T. K. W. Ling, M. Y. Yung, V. K. S. Leung,

E. K. W. Ng, M. K. K. Li, A. F. B. Cheng, and A. K. C. Li.1995. Antibacterial

treatment of gastric ulcers associated with Helicobacter pylori. N. Engl. J. Med.332:139–142.

21. Tee, W., J. R. Lambert, and B. Dwyer.1995. Cytotoxin production by

Heli-cobacter pylori from patients with upper gastrointestinal tract diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol.33:1203–1205.

22. Tomb, J. F., O. White, A. R. Kerlavage, R. A. Clayton, G. G. Sutton, R. D.

Fleischmann, K. A. Ketchum, H. P. Klenk, S. Gill, B. A. Dougherty, K. Nelson, J. Quackenbush, L. Zhou, E. F. Kirkness, S. Peterson, B. Loftus, D. Richardson, R. Dodson, H. G. Khalak, A. Glodek, K. McKenney, L. M. Fitzgerald, N. Lee, M. D. Adams, E. K. Hickey, D. E. Berg, J. D. Gocayne, T. R. Utterback, J. D. Peterson, J. M. Kelly, M. D. Cotton, J. M. Weidman, C. Fujii, C. Bowman, L. Watthey, E. Wallin, W. S. Hayes, M. Borodovsky,

P. D. Karp, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, and J. C. Venter.1997. The complete

genome sequence of the gastric pathogenHelicobacter pylori. Nature388:

539–547.

23. van Doorn, L.-J., C. Figueiredo, R. Sanna, A. Plaisier, P. Schneeberger,

W. D. Boer, and W. Quint.1998. Clinical relevance of thecagA,vacA, and

iceAstatus ofHelicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology115:58–66.

24. Versalovic, J., D. Shortridge, K. Kibler, M. V. Griffy, J. Beyer, R. K. Flamm,

S. K. Tanaka, D. Y. Graham, and M. F. Go.1996. Mutations in 23S rRNA

are associated with clarithromycin resistance inHelicobacter pylori. Antimi-crob. Agents Chemother.40:477–480.

25. van der Ende, A., Z.-J. Pan, A. Bart, R. W. van der Hulst, M. Feller, S. D.

Xiao, G. N. Tytgat, and J. Dankert.1998.cagA-positiveHelicobacter pylori

populations in China and The Netherlands are distinct. Infect. Immun.

66:1822–1826.

26. Wang, H.-J., C.-H. Kuo, A. A. M. Yeh, P. C. L. Chang, and W.-C. Wang.1998.

Vacuolating toxin production in clinical isolates ofHelicobacter pyloriwith differentvacAgenotypes. J. Infect. Dis.178:207–212.