72-83. ISSN 2406-2588 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5937/ejae13-10012 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record:

http://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/2728/

Document Version: Article

Creative Commons: Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law.

The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team.

We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis.

CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION, LUXURY PRODUCTS

AND COUNTERFEIT MARKET IN THE UK

Trang Huyen My Pham, Muhammad Ali Nasir

Leeds Beckett University, Faculty of Business and Law, Leeds, United Kingdom

Abstract:

The fast growth of fashion brands and the popularity of counterfeit goods has posed certain challenges to the existing and new luxury fashion brand players. This study elaborates on the factors driving the market for counterfeit products in the UK. The data collected by means of survey questionnaires from 306 respondents and empirical techniques including descriptive and inferential statistics (correlation and multiple regression analysis), have shown that the consumers have a negative attitude towards counterfeit luxury products. However, they showed fewer tendencies to seek for a brand whose counterfeit cannot easily be found and preferred to buy a genuine rather than a counterfeit. In terms of frequency of purchase, reversion to counterfeit has negative impact, unlike the tendency to seek a brand whose counterfeit is hard to find. The overall results show that the attitude and acceptance of counterfeit do not greatly prevail in the market. However, about 27% of respondents demonstrated either a positive or a neutral tendency towards counterfeit products, which could have serious implications for the luxury goods market.

Key words:

luxury fashion brands, consumer choice, counterfeit products, conspicuous consumption.

658.62.018.2

DOI: 10.5937/ejae13-10012

Original paper/Originalni naučni rad

INTRODUCTION

Luxury1 fashion brands are no longer the privi-lege of the upper class. The emerging middle class is being more open-minded, their demand for luxury fashion brands is increasing along with their income, as they are becoming potential consumers of luxury fashion brands (Kauppinen-Räisänen et al., 2014). The retail sector is a major contributor to the UK economy, employing a total of 4.3 million people in 2012, which is 15.9% of the overall population

1 “Luxury is derived from the Latin word Luxus, which translates to “excess”, thus luxury products in general refer to products that lead to condition of abundance, things that provide pleasure or comfort but are not absolutely necessary” (Fuchs et al., 2013).

73 There is a growing presence of counterfeit

goods in the UK, which may pose serious prob-lems for the company, consumers and the overall economy (Okonkwo, 2007). Sonmez et al. (2012) argue that it destroys the rarity of luxury fashion products that impact customers’ decision-mak-ing. In the current climate, luxury fashion brands do not only compete with other luxury fashion brands, but also with counterfeit manufactur-ers. Although certain efforts have been made to search for manufacturers of counterfeit goods and prevent their activities, this situation has not im-proved and even seems to be deteriorating (David, 2011). From the customer’s perspective, it might be that counterfeiting influences customers’ views about genuine luxury fashion items. Therefore, it is necessary to be able to understand customers’ opinions about counterfeit. The aim of this study is to become conversant and gain better under-standing of the current counterfeit luxury brand market in the UK and to identify the key factors that customers believe have the greatest bearing on the purchase of counterfeit luxury fashion brands.

There are numerous studies that seek to identify the main dimensions of luxury, such as Fionda et al. (2008), Berthon et al. (2009), Christodoulides et al. (2009), and Hudders, et al. (2013). More specifical-ly, in the context of luxury fashion products, Walley et al. (2013) observed the key dimensions of luxury from a UK consumers’ perspective. Various studies have been conducted in terms of particular factors affecting customers’ choice, such as price (Hwang et al., 2013), quality (Husic et al., 2009) and brand reputation, quality and appropriateness (Derry et al., 2014). A vast majority of research is focused on defining reasons for purchasing luxury fashion brands (status promotion, self-image, gifting its owners). We have some evidence on the counter-feit luxury products, such as the study by Doss and Robinson (2013) which compared and contrasted the attitude of young US females towards luxury fashion brands and their counterfeits2. However,

2 Doss and Robinson (2013) found that the perceptions of the luxury brand were significantly higher than those for the counterfeits of that brand. Moreover, the luxury perceptions

this study is not gender specific, nor it compares the perception of luxury fashion brands with their counterfeits, but it is rather investigating the atti-tude of British consumers towards the counterfeits of luxury products, and not the counterfeits of the products they have used. There isn’t sufficient evi-dence on the attitude of British consumers towards counterfeit luxury products. The UK luxury fashion market makes a considerable contribution to the global market and national economy, while previ-ously cited figures give some idea about its size. Having that in mind, the study attempts to find out the reasons that customers take into consideration when buying a counterfeit luxury fashion product. Specifically, it explores the most important factors that affect customer’s choice of luxury fashion brands in the UK by posing three statements to the respondents of survey questionnaires:

a) Do they mind if the product is counterfeit (no effect on decision)?

b) Do they seek the brand whose fake version is hard to find in the market?

c) Would they buy the fake rather than the genuine product?

The answers to these three questions on a five-point Likert scale range from strongly agree to strongly disagree and will help us to understand the consumers’ attitude towards counterfeit prod-ucts. Moreover, we would also observe the impact of these attitudes on the frequency of purchase of luxury products. Nevertheless, this treatise is an effort to understand customers’ attitudes to luxury fashion brands in terms of their current counter-feits in the UK market. In the next section, the authors will examine the existing evidence on the subject and discuss research methodology to pro-vide an insight into the methods being employed, prior to reporting the findings and concluding remarks. The novelty of the research should be emphasized and the subject is well-documented in the up-to-date literature.

LUXURY BRAND & COUNTERFEIT

People purchase luxury fashion brands for a number of reasons. Firstly, they need clear hi-erarchy to define their high position in society (Kapferer, 2014). Secondly, luxury items link to psychological values, as people in the upper-class desire to distinguish themselves from others, while people belonging to the lower class attempt to be perceived as in a higher status, and they consider luxury consumption as a means of achieving that (Veblen, 2009). Thirdly, purchasing luxury fashion products also nurtures owner’s identity and self-image (Hudders et al., 2013). Furthermore, people buy luxury items for self-gifting purposes, as a way leading to personal reward, compliance (Lourreiro & Araujo, 2014), relieving stress and cheering up (Kauppinen-Räisänen et al., 2014). Moreover, pre-mium and reliable quality is a reason for consum-ing luxury items, as mentioned by Hudders et al., (2013). Fashion consciousness was also stated as a reason for luxury fashion brands consumption (Maden et al., 2015). However, if we look at these reasons for buying luxury products, the question imposes as to the number of those that could be served by counterfeit luxury products whose prices are not that exorbitant.

By highlighting the main role of the brand’s name, identity, awareness and loyalty, Okonkwo (2007) claims that the first thing that comes to a luxury customer’s mind is “brand”, which probably describes its history, language and total offerings. Similarly, Palmer (2009) suggested that custom-ers seek their own perceived pcustom-ersonality through brand image. Moreover, brands are chosen when the image they create matches the needs, values and lifestyles of customers. Now, the question imposes as to the number of needs and values that could be achieved using a counterfeit product. However, the study by Han et al. (2010) showed that there are two groups of luxury consumers. The first group prefers less prominent luxury brands, while the second one opts for those more prominent. In the former group, customers focus on the real quality

and function of luxury products rather than on the brands with conspicuous signs; the latter one might lack any deep knowledge of luxury brands and might be keen on purchasing prominent products to show off. If that division holds, the latter should be more prone to accepting the counterfeit, as it serves the purpose of conspicuous consumption.

75 who are keen on showing off their status,

counter-feit does not only have a negative status. Namely, once the customers purchase a fake product, they may not buy it again due to its poor quality, and would opt for the genuine one (Ritson, 2010). For instance, despite having the largest share of coun-terfeit products in the handbag market, the Louis Vuitton sample is considered, even it is well-known to be in the most favourable position. This might be the result of customers’ loyalty (Newman & Dhar, 2014). Overall, counterfeit is identified as the rea-son for a decreasing demand for luxury products, but somehow it may or may not persuade custom-ers into choosing genuine luxury products. When analyzing US young female consumers, Doss and Robinson (2013) found that the perceptions of the luxury brands were significantly higher than those for the counterfeits of the same brands. Moreover, the luxury perceptions of those whose last handbag acquisition was a luxury brand significantly dif-fered from luxury perceptions of those whose last handbag acquisition was a counterfeit brand. That implies that the counterfeit may repel the consumer from the future purchase of the genuine product. Customers mainly choose to be loyal to genuine luxury brands due to their quality, as an impor-tant feature of any product, which is rather hard to define. A product is normally evaluated as poor quality when it fails to meet the buyer’s expecta-tions (Palmer, 2009). Accordingly, if the counterfeit product meets the customer expectations, it should be considered a quality product. However, along with tangible there are intangible aspects of qual-ity, such as experience and feeling (Yuen & Chan, 2010). Hence, if a counterfeit is doing well on both aspects, a rational consumer should drive the same amount of utility from a counterfeit as from an au-thentic luxury product. Nevertheless, the net utility should be great as there is less expenditure involved, which may cause some disutility3.

3 Net utility of counterfeit = total utility from consumption – disutility of regret and guilt

Net utility of authentic = total utility from consumption – disutility of paying the high prices

On the decision matrix if the utility of counterfeit is > than utility of authentic one should use counterfeit and other way round.

for a high-quality brand that is not too expensive. Could it be a counterfeit? One might suggest that the increase in income may discourage the price and could lead to an increased demand for luxury goods (Shilling, 2007). In the Maslow’s hierarchy model, the esteem dimension can be seen as the re-spect from other people, which can be deserved by buying a luxury brand to show their status, as well as their high income (Carlin et al., 2013). Moreo-ver, the demand for luxury goods will be higher in societies with larger income disparity where a need to confirm one’s social status is more pronounced (Ray et al., 2013). If that is the case, the question imposes at to whether counterfeit products meet that purpose, particularly when the price is low and income high but limited.

Place or delivery of products is also an impor-tant factor in terms of convenience and availabil-ity, customer’s value, speed and availability (Den-nis et al., 2004). Luxury fashion brand stores are usually located in city centers or busy traffic areas in order to attract customers’ attention. However, as counterfeits are considered illegal, such market cannot operate freely like authentic luxury brand stores. Although it may bring some advantages, such as cost of selling associated with physical presence, it deprives the customer of the pleas-ure and satisfaction of purchsing luxury goods in retail stores. Nevertheless, the related aspect is the promotion of counterfeit products and com-munication with the customer. The promotion tools such as advertising, personal selling, public relations, sale promotion, sponsorship and direct marketing methods may not be used by the coun-terfeit product makers and sellers in the same way as by authentic producers of luxury products and brands. As suggested by Khan (2014) with devel-opment of technology, promotion is considered the key aspect for promoting brand image in the contemporary market, and counterfeit brand mak-ers could be metaphorically described as parasites who earn their living from the promotion of au-thentic brand makers.

METHODOLOGY & DATA

In the case of counterfeit luxury fashion brands and consumers’ attitude towards them, quantita-tive method can be used to acquire certain find-ings. We collected the primary data by survey questionnaires using self-administered question-naires due to the big sample size and limited time. This survey included four statements. The first three statements were under the main question: To what degree does the fact that a product is counter-feit affects your choice when you make a decision to purchase a luxury fashion brand product? The respondents are given three specific statements: a) I do not mind that the product is counterfeit (no effect on decision) b) I seek the brand whose fake version is hard to find in the market and c) I would buy the fake rather than the genuine product. The respondents were asked to choose the answer they consider most relevant and their responses ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree. In the fourth statement, they were asked about the frequency of purchase of luxury fash-ion brands. The whole questfash-ionnaire was divided into 2 sections including the demographic and the main part. The data collection process was kept confidential and anonymous. All participants gave their consent and were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity and were not given any financial or other incentives. Subsequently, participants vol-unteered by answering questionnaires in person. Around 306 responses were included in this study. We performed four different methods of analysis, including reliability analysis, descriptive analysis, correlation and multiple linear regression analysis.

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

77

RELIABILITY ANALYSIS

We first need to perform the reliability test to see whether our data was reliable or not. To that end, we performed the Cronbach’s alpha to test reliability of our data. As a benchmark, we relied on the statement of Nunnally (1978) who suggested that if alpha values are 0.70 or higher, the scale should be considered acceptable, while values below the benchmark make it unreliable. The results are shown in Table 2.

Cronbach’s alpha Number of items

[image:7.567.65.507.71.524.2]0.71 22

Table 2. Reliability analysis

As shown, the Cronbach’s alpha is 0.710 > 0.7, which implied that the collected data is reliable and that it makes sense to carry on with it.

Demographic Frequency Percentage (%)

Gender Male

Female

128 178

41.8 58.2

Total 306 100

Age

<18 18-25 26-35 36-45 >45

12 109 84 41 60

3.9 35.6 27.5 13.4 19.6

Total 306 100

Income

Less than £10,000 £10,000 to £14,999 £15,000 to £24,999 £25,000 to £34,999 £35,000 to £44,999 £45,000 to £54,999 £55,000 above

107 37 70 38 21 12 21

35.0 12.1 22.9 12.4 6.9 3.9 6.9

Total 306 100

Highest educational qualification

Primary School High School College diploma Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree Doctorate degree

1 41 52 101 86 25

0.30 13.4 17.0 33.0 28.1 8.2

Total 306 100

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

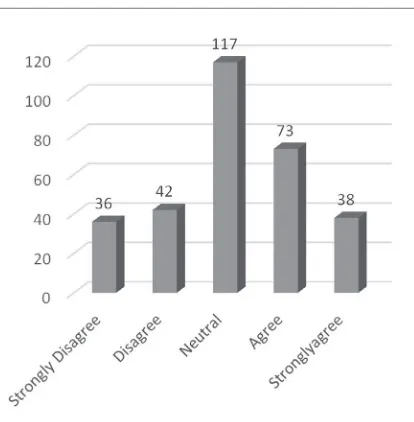

Descriptive statistics is an important way of learning about the features of availabe data and its implications for our study. Customers were asked about counterfeit luxury fashion products and their answers ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree (reponses were coded from 1 to 5). Fig-ures 1-3 present visual depictions of consumers’ responses.

In response to our first statement that “I do not mind that the product is counterfeit (no effect on decision), most of the respondents strongly

disagree with the statement, thus suggesting that consumers do care if the product is counterfeit.

In response to the second statement that if they seek the brand whose fake version is hard to find in the market, most of the customers provided neu-tral answers, suggesting that the consumers are not putting enough effort into ensuring that the product is not fake. This could be related to the trust associated with shopping from designated places. The second largest group included those who agreed that they seek the brand whose fake is hard to find. The last statement put forward to

[image:8.567.294.501.271.482.2]re-Figure 1. I do not mind that the product is counterfeit (no effect on decision)

[image:8.567.68.272.273.479.2]Figure 2. I seek the brand whose fake version is hard to find in the market

[image:8.567.176.386.527.717.2]79 spondents was that they would buy the fake rather

than the genuine one.

Figure 3 depicts the responses obtained. It showed that most of the consumers strongly dis-agree or disdis-agree with the statement. It showed that the consumer has disgust towards the coun-terfeit products. Hence, if the demand of luxury products would be for the purpose of conspicuous consumption, the counterfeit could be considred appropriate. Even though there is still a substan-tial number of respondents that either strongly agreed or agreed with the idea that they would prefer counterfeits. When putting them together with neutral, it makes over 27% of respondents which is still a considerable number.

Therefore, we come to the descriptive statis-tics and look at the measures of central tendency (mean, median & mode) and dispersions (standard deviation). The responses were coded from 1 to 5 in order, equal to strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree, respectively for the first statement. The rationale was to gauge the degree of aversion as respondents chose from strongly agree 1 to strongly disagree 5. The results of descriptive statistical analysis are summarized in Table 3 below.

Coun-terfeit Aversion

Seek brand which hard to find fake

Buy fake rather

than genuine

N Valid 306 306 306 Mean 3.483 3.098 2.006 Median 3.500 3.000 2.000

Mode 5 3 1

Std. Deviation 1.257 1.135 1.049 Minimum 1.00 1.00 1.00 Maximum 5.00 5.00 5.00

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics: Opinions about coun-terfeit goods

Source: Authors’ calculations using questionnaire data

In response to the first statement i.e. Do not mind that the product is counterfeit (no effect on decision), it showed that with mode of 5 (strongly disagree) most respondents strongly disagree with purchasing counterfeit. Moreover, the values of the mean and median are about 3.5, which shows that the average opinion is between neutral and disagree. Hence, the consumers’ response to the measures of central tendency was negative towards counterfeit.

The answers to the second statement were designed to range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The statement was “I seek the brand whose fake version is hard to find in the market”. It can be seen that mean, mode and me-dian have a similar score i.e. 3. That means that most people have neutral opinion, which implies that although the attitude towards the counter-feit might be negative, there is still an element of neutrality or less effort when it comes to a luxury brand whose counterfeit is hard to find, which implies trust in what they are getting.

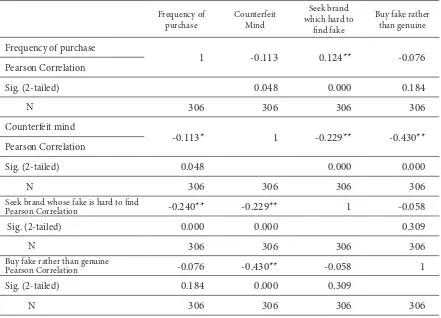

CORRELATION ANALYSIS

In order to examine the association between the observed variables, an inferential statistical analysis was performed. We started with analyzing correlation between the frequency of purchase and attitude towards counterfeits (Table 4).

As can be seen, when asked if they mind that the product is counterfeit, customers’ answers provided significant negative correlation with the frequency of purchase at 5% significance level (sig value- 0.04<0.05), thus implying that there is a negative correlation between the frequency of pur-chase of luxury products and counterfeit aversion. Hence, those who have greater tendency to mind the counterfeit seem to less frequently purchase luxury products. Moreover, the statement “Seeking the brand whose fake version is hard to find in the market” has significant positive correlation with the frequency of purchase at 1% significance level

(sig value 0.000 < 0.001), thus implying that those who agree with seeking a luxury brand whose fake is hard to find in the market were more frequent purchasers of luxury brands. The last statement of buying a fake rather than a genuine product showed a negative though insignificant correla-tion with the frequency of purchase, thus implying that those who agree with the purchase of the fake rather than the genuine products are less frequent buyers. However, the results were not highly sig-nificant (sig value 0.148 > 0.05).

REGRESSION ANALYSIS

The correlation analysis does not imply cau-sation. Therefore, in order to analyze the cause and effect relationship among the variables, the regression analysis was performed. The impact of perception about counterfeit was analyzed based on the purchase frequency. The model took the following form:

Frequency of purchase Counterfeit Mind which hard to Seek brand find fake

Buy fake rather than genuine

Frequency of purchase

1 -0.113 0.124** -0.076

Pearson Correlation

Sig. (2-tailed) 0.048 0.000 0.184

N 306 306 306 306

Counterfeit mind

-0.113* 1 -0.229** -0.430**

Pearson Correlation

Sig. (2-tailed) 0.048 0.000 0.000

N 306 306 306 306

Seek brand whose fake is hard to find

Pearson Correlation -0.240** -0.229** 1 -0.058

Sig. (2-tailed) 0.000 0.000 0.309

N 306 306 306 306

Buy fake rather than genuine

Pearson Correlation -0.076 -0.430** -0.058 1

Sig. (2-tailed) 0.184 0.000 0.309

N 306 306 306 306

[image:10.567.64.505.383.701.2]81

( ) ( 1) ( 2) ( 3) t

Y PurchaseFrequancy = +a b X +bX +b X +e

Where a is the constant, Y is the response vari-able (frequency of purchase) and X1 – X3 are ex-planatory variables, βt are the (n x n) coefficient matrixes and εt is the (n x 1) white noise or unob-servable vector process with the assumptions of no autocorrelation and independent distribution, i.e. et ˜ N (0, σ2).

Dep. Variable Frequency of Purchase Sig

Constant 3.562 0.000 (7.469)

Counterfeit Mind/ Reversion

-0.128

0.075 (-1.788)

Seeking hard to find counterfeit

0.257

0.000 (3.585)

Buy fake rather than genuine

-0.151

0.071 (-1.814)

F test 7.744 0.000

R squared 0.071

N 306

[image:11.567.64.276.234.469.2]Note: absolute ‘t’ ratio IN BRACKETS

Table 5. Regression analysis, opinions about counterfeit & frequency of purchase

The results of our regression analysis show that for our first statement, “Do not mind counterfeit”, which we call the counterfeit reversion showed a negative impact (- 0.128) on the frequency of purchase, at 10% significance level (sig value 0.075 > 0.05). It implied that the counterfeit reversion has adverse effects on the frequency of purchase of luxury products. Hence, a consumer with more tendency of counterfeit reversion will buy a luxury brand less frequently. On the other hand, agreement with seeking hard to find the fake one demonstrated a positive impact (0.257) on the fre-quency of purchase, which was at 1% significance level (0.00 < 0.01). It implied that the consumer

with the tendency of seeking hard to find coun-terfeit of luxury brands would buy luxury brands more frequently. It can be said that those who are more careful about the choice of luxury fashion products will buy more frequently. It to some ex-tent reduces the fears of Sonmez et al. (2012) that counterfeit might put genuine brands at risk. The last statement Buy the fake instead of the genuine product showed a negative coefficient (- 0.151) on frequency of purchase, which was at 10% level of significance (0.07 < 0.10), thus implying that those who have a tendency to agree with the idea of buying the fake instead of the genuine product ac-tually buy the luxury brand less frequently. These results can be explained by saying that if customers purchase fake products they would not buy the genuine and the other way round. It is quite oppo-site from Ritson’s (2010) idea that customers will return to luxury fashion brands after experiencing fake products. Additionally, customers just show positive opinion on the idea of seeking a brand whose fake version is hard to find, but people who agree with this statement tend to purchase luxury fashion brands more frequently. Overall, in terms of all explanatory variables and their relationship with the response variable (frequency of purchase), we have the F-statistics value of 7.744, which was greater than the critical value for the F-test (2.083), the results were also significant (0.000 < 0.01) at 1% significance level. In terms of the goodness of fit, our results show a modest explanatory power of the model (7.1%) in explaining the level of fre-quency of purchase. However, it does explain how these tendencies and attitudes towards counterfeit products prevail and influence the consumer be-haviour in their own capacity.

CONCLUSION

counterfeits was rather neutral. However, those with greater tendency of seeking brand whose fake is hard to find would buy luxury brands more frequently. Our findings also imply that although comparatively most of the consumers will prefer to buy genuine luxury products, it is not only the matter of conspicuous consumption. Namely, a significant number of consumers would prefer to buy counterfeit rather than authentic and genuine luxury products. In terms of frequency of pur-chase of luxury product, those who agree with the idea of buying fake rather than genuine products, buy luxury products less frequently.

Nevertheless, this study has certain limita-tions. For instance, we are yet to discover why these tendencies exist among the consumers and to identify the drivers of such consumer behavior. The authors shall more thoroughly address these issues in some future research.

REFERENCES

Carlin, A., Verel, S., & Collard, P. (2013). Modeling lux-ury Consumption: An Inter-Income Classes Study of

Demand Dynamics and Social Behaviors. Retrieved

November 20, 2014, from http://ofce-skema.org/ wp-content/uploads/2013/0 6/carlin.pdf.

Chris, R. (2014). The retail industry: statistics and policy. Retrieved November 20, 2014, from http://democ-racy.middlesbrough.gov.uk/aksmiddlesbrough/ images/att1005416.pdf.

Christodoulides, G., Michaelidou, N., & Li, C.H. (2009). Measuring perceived brand luxury: An evaluation of the BLI scale. Journal of Brand Management, 16, 395-405. doi:10.1057/bm.2008.49.

David, F. (2011). Intellectual Property No Credit for Fake Brands! Business Law Review, 32(3), 56-58. Dennis, C., Fenech, T., & Merrilees, B. (2004).

E-retail-ing. London: Routledge.

Doss, F., & Robinson, T. (2013). Luxury perceptions: luxury brand vs counterfeit for young US female consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and

Man-agement: An International Journal, 17(4), 424-439.

doi:10.1108/JFMM-03-2013-0028.

Eaton, B.C., & Eswaran, M. (2009). Well-being and afflu-ence in the presafflu-ence of a Veblen Good. The Economic

Journal, 119(539), 1088-1104.

doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02255.x.

Fionda, A.M., & Moore, C.M. (2008). The anatomy of the luxury fashion brand. Journal of Brand Management, 16, 347-363. doi:10.1057/bm.2008.45.

Fuchs, C., Prandelli, E., Schreier, M., & Dahl, D.W. (2013). All that is users might not be gold: How labeling prod-ucts as user designed backfires in the context of luxury fashion brands. Journal of Marketing, 77(5), 75-91. doi:10.1509/jm.11.0330.

Han, Y.L., Nunes, J.C., & Dreze, X. (2010). Signaling status with luxury goods: The role of brand promi-nence. Journal of Marketing, 74(4), 15-30. doi:10.1509/ jmkg.74.4.15.

Hudders, L., Pandelaere, M., & Vyncke, P. (2013). Con-sumer meaning making: The meaning of luxury brands in a democratised luxury world. International Journal

of Market Research, 55(3), 69-90. doi:

10.2501/IJMR-2013-000.

Husic, M., & Cicic, M. (2009). Luxury consumption factors. Journal of Fashion Marketing and

Manage-ment: An International Journal, 13(2), 231-245.

doi:10.1108/13612020910957734.

Hwang, Y., Ko, E., & Megehee, C.M. (2013). When higher prices increase sales: How chronic and manipulated desires for conspicuousness and rarity moderate price’s impact on choice of luxury brands. Journal of

Business Research, 67, 1912-1920.

doi:10.1016/j.jbus-res.2013.11.021.

Kapferer, J.N. (2014). The artification of luxury: From artisans to artists. Business Horizons, 57(3), 371-380. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2013.12.007.

Kauppinen-Räisänen, H., Gummerus, J., von Koskull, C., Finne, A., Helkkula, A., Kowalkowski, C., & Rindell, A. (2014). Am I worth it? Gifting myself with luxury.

Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An

International Journal, 18(2), 112-132. doi:10.1108/

JFMM-04-2013-0062.

Khan, M.T. (2014). The Concept of ‘Marketing Mix’ and its Elements (A Conceptual Review Paper). International

Journal of Information, Business and Management, 6(2),

95-107.

Kuksov, D., & Xie, Y. (2012). Competition in s status goods market. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(5), 609-623. Lourreiro, S.M.C., & Araujo, C.M.B.D. (2014). Luxury

values and experience as drivers for consumers to recommend and pay more. Journal of Retailing and

Consumer Services, 21(3), 394-400.

doi:10.1016/j.jret-conser.2013.11.007.

Maden, D., Goztas, A., & Topsumer, F. (2015). Effects of brand origin, fashion consciousness and price-quality perception on luxury consumption moti-vations: an empirical analysis directed to Turkish consumers. Advances in Business Scientific Research

83

Newman, G.E., & Dhar, R. (2014). Authenticity is con-tagious: Brand Essence and the original source of production. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(3), 371-386. doi:10.1509/jmr.11.0022.

Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Okonkwo, U. (2007). Luxury fashion branding: Trends,

tactics, techniques. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Olorenshaw, R. (2011). Luxury and the recent economic crisis. Vie & Sciences Économiques, 188(2), 73-90. doi:10.3917/vse.188.0072.

Palmer, A. (2009). Introduction to marketing: Theory and

practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ray, A., & Vatan, A. (2013). Demand for Luxury Goods in

a World of Income Disparities. Retrieved November

20, 2014, from https://hal-pse.archives-ouvertes.fr/ hal-00959398/document.

Ritson, M. (2010). The sham surrounding fake luxury

brands. Retrieved November 12, 2014, from https://

www.marketingweek.com/2010/09/08/the-sham-surrounding-fake-luxury-brands/.

Shilling, A.G. (2007). Small luxuries. Retrieved No-vember 28, 2014, from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com. ezproxy.leedsbeckett.ac.uk.

Sonmez, M., Yang. D., & Fryxell. G. (2012). Interac-tive role of Consumer Discrimination and Brand-ing against CounterfeitBrand-ing: A study of Multinational Managers’ Perception of Global Brands in China.

Journal of Business Ethnics, 115(1), 195-211.

Sophie, H. (2010). Effect of counterfeits on the image of luxury brands: An empirical study from the customer perspective. Journal of Brand Management, 18(2), 159-173. doi:10.1057/bm.2010.28.

Timberlake, C. (2014). Michael Kors wins over Europe’s fashionistas. Bloomberg Businessweek, 4377, 27-28. Veblen, T. (2009). The Theory of the Leisure Class: An

Economic Study of Institutions. Oxford: Oxford

Uni-versity Press.

Walley, K., Custance, P., Paul, C., & Perry, S. (2013). The key dimensions of luxury from a UK consum-ers’ perspective. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 31(7), 823-837. doi:10.1108/MIP-09-2012-0092. Yuen, E.F.T., & Chan, S.S.L. (2010). The effect of

re-tail service quality and product quality on customer loyalty. Journal of Database Marketing & Customer

Strategy Management, 17, 222-240. doi:10.1057/

dbm.2010.13.

Received: March 9, 2016 Correction: April 18, 2016 Accepted: April 27, 2016

UPADLJIVA POTROŠNJA, LUKSUZNA ROBA

I TRŽIŠTE FALSIFIKATA U VELIKOJ BRITANIJI

Rezime:

Brz razvoj modnih brendova i popularnost falsifikovane robe predstavlja veliki izazov za postojeće i nove proizvođače i korisnike luksuznih modnih brendo-va. Ovaj rad ispituje faktore koji podstiču tržište falsifikovane robe u Velikoj Britaniji. Na osnovu podataka prikupljenih iz upitnika u kojem je učestvovalo 306 ispitanika i korišćenjem empirijskih tehnika, poput deskriptivne i inferen-cijalne statistike (korelaciona i višestruka regresiona analiza), može se zaključiti da potrošači imaju negativan stav prema falsifikatima luksuznih brendova. Međutim, oni pokazuju slabiju tendenciju prema kupovini brendova čije je falsifikate teško naći i u tom slučaju radije kupuju original. Kada je reč o uče-stalosti kupovine, ispitanici imaju averziju prema falsifikovanoj robi i nastoje da kupuju brendove za koje je teško naći falsifikat. Generalno posmatrano, rezultati pokazuju da zagovaranje i prihvatanje falsifikovane robe nije toliko prisutno na tržištu. Međutim, oko 27% ispitanika ima pozitivan ili neutralan stav prema falsifikovanoj robi, što u velikoj meri utiče na tržište luksuzne firmirane robe.

Ključne reči:

luksuzni modni brendovi, izbor potrošača,

falsifikati,