Munich Personal RePEc Archive

Capital Inflows and Real Exchange Rate

Appreciation in Latin America

Reinhart, Carmen and Calvo, Guillermo and Leiderman,

Leonardo

University of Maryland, College Park, Department of Economics

1992

Online at

https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/13843/

IhZF WORKING PAPER

Q 1992 International Monekary Fund

This is a Working Papwand the author would welcome any comments on the present texL C ~ ~ t i o n s should refer to a Wwhng Paper or the International Monetary Fund, men- tioning the auhor, and rhe date of issuance. The views expressed me those of the author and do nor necessarily

rcprrsent those of the Fund.

INTERNATIONAL

MONETARY

FUNDResearch Department

Capital Inflows and Real Exchange Rate Appreciation

L/

Prepared by Guillermo A . Calvo, Leonarda Leiderrnan 2J, and Carmen M. Reinhaxt

August, 1992

Abstract

The characteristfcs of recent c a p i t a l inflows into Latin America

are discussed. It is argued that these inflows are partly explained

by

conditions outside the region, like recession in the U n i t e d States and

lower international interest rates.

This

suggeststhe

possibilitythat

a reversal of those conditions

may

lead to a future c a p i t a l outflow,fncreasing t h e macroeconomic vulnerability

of

LatinAmerican

economies.Policy options are argued to be lfmited.

JEL Classification Numbers :

GI, F41

1J

An

earlier version of t h i s paper was presented at seminars atthe

~ o r l d Bank and Inter-American Development Bank,

The

authors w i s h to thank the p a r t i c i p a n t s at these seminars, numerous colleagues and, inparticular,

K.

Bruno, S. Calvo,P.

Clark,E.

Fernandez-~rias andM.

Kiguel for their helpful suggestions.2/

Mr.

Leiderrnan is on leave From t h e Department of Economics at-

-

ii

-

Table of Contents

Summary

I.

Introduction11. The Accounting of C a p i t a l Flows

1x1. Stylized Facts

1 . Anatomy o f c a p i t a l inflows

2 . Real exchange rate appreciation 3 . Rates of return differentials

4 . Other macroeconomic developments 5 . Previous episodes of c a p i t a l inflows

6. External factors

IV.

Roleof

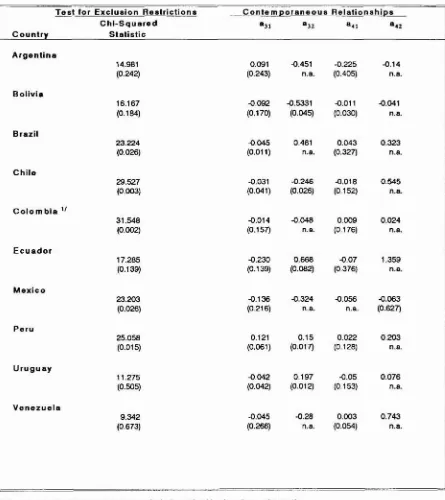

External Factors: Econometric Analysis1. Camovement of reserves and the real exchange rate 2 . Quantifying the role of external factors

V .

Policy

ImplicationsReferences

Text Tables

Charts

Latin America: Balance of Payments,

1973-91

Latin

America: Itemsin

the Capital AccountLatin America: Macroeconomic Indicators

U . S . Balance

of

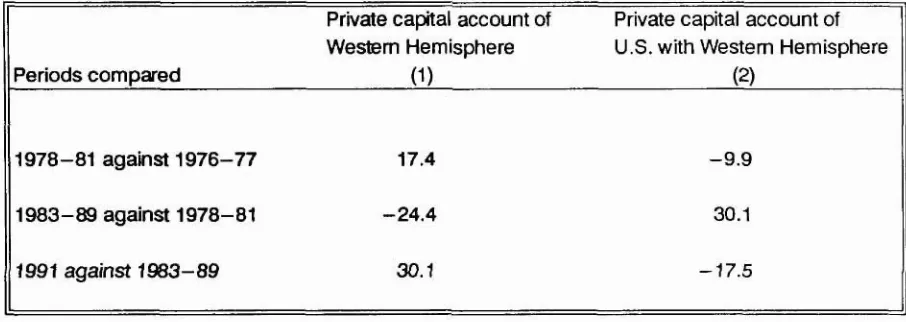

PaymentsChanges in Capital Accounts

Establishing

the

Gomovementin

Macroeconomic SeriesContemporaneous Correlations of the Regional Variables w i t h Selected

U. S

.

IndicatorsCausality Tests

Tests f o r the Significance

of

the Foreign FactorsDecomposition

of

Variance: Real Exchange RateDecomposition

of

Variance: O f f i c i a l Reserves1. Secondary Harket Prices f o r Loans

2 . T o t a l Reserves Minus

Gold

3 , Real Effective Exchange Rate

4 . Stock Market Performance 5 . Interest Rate Spreads

6.

Risk

and Returns7 . First Principal Components

Charts

8 . The

External Variables

2

6a9 . Response

of

O f f i c i a l Reserves to a One-Standard DeviationShock

in

the First Foreign Factor 30a10.

Responseof

the

R e a l Exchange Rate to a One-StandardDeviation in the First Foreign Factor 30b

During the p a s t t w o years, Latin America has received s i z a b l e i n t e r -

national c a p i t a l flows, amounting to $24 billion in 1990 and $40 billion

in 1991. In most cases, they have been accompanied by a marked accumulation

in international reserves, significant appreciations in real exchange rates, booming stock markets, faster economic growth, and wider current account

deficits. Although the restoration o f voluntary a c c e s s to international capital markets a f t e r nearly a decade

has

been heralded as a positivedevelopment, the resurgence in c a p i t a l i n f l o w s has a l s o been a source of concern to polccymakers in the region, who f e a r , in p a r t i c u l a r ,

that

theaccompanying real exchange rate a p p r e c i a t i o n w i l l adversely a f f e c t the export sector. In addition, g i v e n that the previous c a p i t a l inflow e p i s o d e was f o l l o w e d

by

t h e debt c r i s i s of the 1980s, t h e r e are fears that some ofthe capital k n f l o w s are of the " h o t money" variety. These highly specula-

tive flows could be reversed on s h o r t notice and, p o s s i b l y , spark a domestic

financial

crisis.This paper focuses on t w o a s p e c t s of the present c a p i t a l inflow

phenomenon. F i r s t ,

in

an e f f o r t to determine h o w vulnerable these economiesare to an unexpected reversal in c a p i t a l flows, it a s s e s s e s quantitatively

to what extent the recent increase i s due t o external forces. Second, k t

discusses the form and timing o f the a p p r o p r i a t e policy r e s p o n s e , examining t h e pros and cons of a menu of p o l i c y measures, including t a x e s o n c a p i t a l imports, trade policy, f i s c a l tightening, central bank sterilized and

nonsterilized intervention, and banking regulations.

The empirical analysis indicates that capital is returning to mast L a t i n Amerfcan countries despite considerable differences in domestic p o l i c i e s and macroeconomic conditions. External f a r c e s , particularly

developments in t h e United S t a t e s , have played an i m p o r t a n t role i n

inducing capftal flaws i n t o Latin America. The sharp decline in U.S.

interest rates, the continuing recesslon, and capital account developments

in the United States have encouraged a p o r t f o l i o s h i f t toward L a t i n American

assets. The policy analysis suggests t h a t , although e x t e r n a l factors be reversed in t h e future, it is dkfficult to advocate sterilized intervention, given t h e fiscal burdens it entails, unless countries a d o p t a strong fiscal

stance and c a p i t a l inflows are expected t o be short-lived. A more cornpre-

hensive

policy intervention m i x , including r a i s i n g marginal reserverequirements on short-term bank d e p o s i t , imposing t a x e s on short-term c a p i t a l imports, or a combination

of

these measures, are v i a b l e p o l i c yI.

IntroductionThe revival of substantial intexnational c a p i t a l inflows to Latin

America Is perhaps t h e most notable and v i s i b l e change

in

the economicsituation of the regian during the l a s t two years.

While

capltal i n f l o w s to Latin America averaged about $ 8billion

a year inthe

secondh a l f

of the1980s,

they

surged to $24 b i l l i o nin

1990

and to $40billfon

by

1991.

Oft h e latter amount, 45 percent went to

Mexico,

and most of the remainder went:to Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Venezuela. Interestingly, capftal fs returning to most L a t i n American countrfes despite the wide

differences

in

macroeconomic policies and economic performance between them.In

mast countries, the increased c a p i t a l inflows are accompaniedby

enappreciation in the real exchange r a t e , booming stock and seal e s t a t e

markets, faster economic growth, an accumulation of international reserves,

and a strong recovery of secondary market prices for foreign loans.

Without doubt, an important part of t h i s phenomenon is explained

by

the fundamental economic and political refarms which have recently taken p l a c e in a nuaber of these countries, including t h e restructuring of theirexternal debts. Indeed, it would have been difficult to attract foreign

c a p i t a l

in

the magnitudes mentioned above w i t h o u t these reforms.Nevertheless, while domestic reform is a necessary

ingredient

f o r c a p i t a linflows,

itonly

p a r t i a l l y explains L a t i n America's forcefulreentry

ininternational capital markets. For instance, domestic reforms alone cannot

explain

why

c a p i t a l inflows have occurredin

countries t h a t had n o tundertaken substantial reforms or why they d i d n o t occur, until only

recently, in countries where reforms where introduced

well

before 1990.In

order f o r domestic reforms toexplain

t h e observed comovement a £ c a p i t a linflows across countries in the region, one would have to posit the

existence of strong reputatfonal externalities (or "contagion" e f f e c t s ) , where reforms

in

some of t h e countries give rise to expectations of futurereforms in other countries in the region.

T h i s

paper maintains t h a t some of the renewal of capital inflows toLatin America is due to external factors, and can be considered as

an

external shock common to

the

region.We

argue that f a l l i n g interest rates,a continuing recession, and balance of payments developments

in

the

UnitedS t a t e s , along

with

developmentsin

other industrialized countries,have

encouraged investors to s h i f t t h e i r resources toLatin

America t o takeadvantage of

renewed

investment opportunities and the increased solvencyin

t h a t region.

J

I

Taking i n t o account economic developments outside theregian helps to explain t h e universality

of

these inflows.From a

historical perspective

then,

the present e p i s o d emay

w e l lbe an

additionalL a t i n America is n o t the o n l y region

that

has experienced increasedc a p i t a l i n f l o w s in 1991. In fact, similar developments have occurred

in

case of

financial shocks in

the Center that a f f e c t thePeriphery, of

the

type stressed by Diaz Alejandroin

severalof

h i s contributions.I

J

International c a p f t a l

inflows

affect the b t i n American economies in at leastfour dimensions.

2J First, they increase the availabilityof

c a p i t a l

in

the

indiv2dual economies. As debtand

equity capital become moremobile

and accessible, domestic agents can better smooth o u t theirconsumption over t i r u e and investors can more promptly react to changes in

expected

profitability.

Second, capital inflows have been associated with a marked appreciationof

the real exchange rate in m o s t of the samplecountries. The

larger

transfer from abroad has to be accompaniedby an

increasein

domestic absorption. Assuming normality of t r a d a b l e andnontradable goods, at the initial real exchange rate domestic residents plan

to spend part

of

the

transfer i n terms of t r a d a b l e goods. This cannotbe an

equilibrium outcome because foreign transfers must,by

definition, be s p e n tentirely

on tradable goods. Therefore, the real exchange satehas

to appreciatein

order to induce a s h i f t away from nontradable and into tradable goods.Third,

c a p i t a l fnflawa impose their own burdens and challengeson

domestgcpolicymaking.

The

desfre by some central banks to attenuate t h edegree

of

real exchange rate appreciation in the short run frequently leadsthem

to actively intervene and purchase from the private sector partof

the inward flow of f o r e i g n exchange. Moreover, the attempt t o avoid domestic monetfzatfon of these purchases has o f t e n l e d the monetary authorities t os t e r i l i z e

someof

theinflows, which tends

to perpetuate ahigh

dornestic/foreign interest rate

differential,

andgives

rise to increased f i s c a l burdens.The

exrent

towhich

the

inflowsare

sustainable

is also o fconcern

tothe

authorities. Thehistory

of Latin America gives

reasonfor

such concern:the

major episodesof

c a p i t a linflows, during the 1920s

and1978-81,

were followed

bymajor

economic crises and c a p i t a l outflows,such

as in t h e

1930s and

the

debt crisisIn

the mid-1980s.Fourth,

c a p i t a l inflows can provide important--yet ambiguous--signals to participants fn world financial markets. On the one hand, an increase inthe

inflows

can be interpreted as reflecting morefavorable

medium- andlong-term

investment opportunities in the receivingcountry.

Yet,on

the

other

hand,

c a p i t a l may pourin

for purely short-term speculative purposesto a country where lack of credibility

of

government policies leads t ohigh

nominal

returns on domestic f i n a n c i a l a s s e t s .In

f a c t , there have been several such episodesin

LatinAmerica, where

lackof

credibility and ashort- term

financial

bubble were assocf atedwith large

inflowsof

%otmoney"

from

abroad.While

it remains tobe

seenwhich

oneof

these t w oscenarios best fits the present episode, she

strong recovery in

secondarymarket prices

of

bankclaims on

severalof zhese

countries (Chart 1) endSee e

.

g.Diaz

A l e jandro(1983,

1984)

.

2

J For a recent study of the e f f e c t s of c a p i t a l movements, s e e

C h a r t

1 .

SECONDARY MARKET

PRICES

FOR

LOANS

{In percent of face value)A R G E N T I N A B O L I V I A

C O L O M B l A

r-

- 7 1

0 76 U R U G U A Y -- --

0 > A

-

0 7 ? J

0.7

4

- -( I b l .

0 6 6 I I

-

- -A n #O *I1 US An m4 )ul 0 9 Jan Ba A+- Jan-41 Jurl-Yi An-12

o * . 0 4 D

-

0 1 0 7 3 '

0 7 - o a s - n a -

o w -

on.. E C U A D O R

P E R U

O 4 1

0 0s

i

---,-..,--- ,--A+. .+ ---+.-. .

.-.

- .-..

. --,---1

a n 18 Ad I a Jln a * A* a* J=rl M Jd P) A n 9t hl P I Jar, 97

various

other

indicators of countryrisk

provide

at least p a r t i a lsignals in

support of the first,more

favorable,

scenario.7211s paper has three main objectives

which

are developed based on datafor ten

Latin

American countries. 2J The f i r s t is t o document the currentepisode of capttal inflows to Latin Amer%ca and to compare it t o

earlier

such episodes. The second is to quantitatively assess the role of externalfactors

in

accounting f o r the observed c a p i t a linflows

and the real exchange rate appreciation. The t h i r d is to elaborateon

the implicationsof

capitalinflows for economic policy

in Latin

American countries. The paper isorganized as follows. Sectton I1 deals,

with

the basic concepts and therelationship between c a p i t a l inflows, the accumulation of reserves, and the

gap between national saving and investment. The stylized facts about

capital

inflows

to the r e g i o n are documented in Section 111,which

includesa comparison w i t h previous e p i s o d e s . S e c t i o n I V provides a quantitative

assessment of t h e role of external factors an the accumulation

of

reservesand

on

the real exchange rate appreciationin the

ten countries considered.The implications of c a p i t a l i n f l o w s for domestic economic policy are discussed

in

Section V .11. The Accountinn of C a w i t a l Flows

International c a p i t a l flows are recorded

in

the non-reserve capital account of the balance of payments.This

account includes all international transactions w i t h a s s e t s o t h e r than o f f i c i a l reserves, such as transactionsin

money, stocks, government bonds, land, factories, and soan.

When an a t i o n a l agent sells en asset to someone abroad, the transaction enters h f s

country's balance of payments as a credit: on the c a p i t a l account and is

regarded as a capital inflow. Accordingly, net borrowing abroad by domestlc

agents ar a purchase of domestic stocks

by

foreigners are considered as capital inflows, whlch respectively represent debt and equityfinance.

Themethodology of the International Monetary

Fund

breaks down c a p i t a lflows

into three main categories: f o r e i g n direct investment, p o r t f o l i oinvestment, and other capital.

The

simplerules

of double-entry accounting ensure that, up tostatistical discrepancies, the capital account surplus

or

n e t capitalinflow

(denoted by KA)

Is

related to the c u r r e n t account surplus (denotedby

CA)and to the official reserves account (denoted by RA) of the balance of

payments through the identity:

1/

For tracingon

the evolutionover

timeof individual

countryratings

-

see, for instance, LDC Debt R e ~ o r t

by

Salmon Brothers.The

countries includedin our

sample are:Argentina, Bolivia,

B r a z f l ,C h i l e , Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

A n important property of the

current

account isthat

it measures the changein

the

economy's net foreign wealth. A country that runs a current accountd e f i c i t must finance

t h i s

d e f l c i t eitherby

a private c a p i t a l inflow or by a reductionin

its o f f t c i a l reserves. In both cases the country is runningdown i t s net foreign wealth. Another important characteristic of the

current account is that national income accounting implies that its surplus

is

equal to the difference between national saving and national investment ( t h a t is, CA = S-I). Accordingly, an increase in thecurrent

account d e f i c i t can be traced to eitheran

increasein

national investment, a declinein

national savings, or any combination of these variables t h a t results in an increased investrnent/savings gap. FSnally, the o f f i c i a l xeserves account records purchases or sales of o f f i c i a l reserve a s s e t sby

central banks. Thus, t h i s account measuresthe

extentof

official foreignexchange intervention by the authorities, and is often referred to as the

o f f i c i a l settlements balance

or

t h e overall balanceof

payments (seefootnote 3

an

page 3 ) .The foregoing discussion i n d i c a t e s that there are t w o polar cases

of

central bank intervention under increased capital inflows. In a no-

intervention scenario, the increased n e t exports of a s s e t s in the c a p i t a l account are financing an increase in net imports of goods and services. Under these circumstances, c a p i t a l inflows would

not

be associated w i t hchanges

in

central banks' holdings of o f f i c i a l reserves. A t the otherextreme is s scenario in which the domestic authorities actively intervene

and purchase

the foreign

exchange broughtin

by

t h e capital inflow. Thus,the increase in

KA

is matched, one-to-one, by an increasein official

reserves {recorded as a reduction

in

RA). In this case, there isno

changein the gap between national saving

and

national investment, n o r is there any changein

the

net foreign wealth of theeconomy. That

is, the c a p i t a linflow would then be

perfectly correlatedw i t h

changesin

o f f i c i a l reserves.In

r e a l i t y ,we

observe fareign exchange market intervention b u t not on a scale thatwould

produce a one-to-one relationship between reservesaccumulation and capital i n f l o w . Put d i f f e r e n t l y , the observed increase in

capital Inflows to Latin America is

partly

matchedby

an increase in the region's current account d e f i c i t andby an

increasein

central banks' o f f i c i a l reserves. The pertinent data are discussedIn

the next section.111. Stvlized Facts

In

this

section we quantify some of the key aspects of the currente p i s o d e

of

c a p i t a l inflows toLatin

America and t h e relatedunderlying

macroeconomic developments.

l

J

To document the regional aspects ofSee a l s o Financial T i m e s (1992), Kuczynski (19921, and Salornon

t h i s phenomenon we aggregate

annual

data and focus on Latin America as awhole.

a/

Monthly data f o rindividual

countries provide greater d e t a i l and are also discussed here andin

the

sectton that follows.The

currentdevelopments are then compared with previous episodes of c a p i t a l inflow.

L a s t , we elaborate

on

the

role of external developments, especially thosein

the United S t a t e s .

1.

Anatomv of c a p i t a l inflowsTable 1 presents a breakdown

of

L a t i n America's balance of payments i n t o its three main accounts. The capital inflows under considerationappear in the form of surpluses

in

the c a p $ t a l account, of about$24

billion in 1990 and about$40

billion in 1991. It can be seenthat

a substantialfraction o f the inflows have been channelled to foreign exchange reserves,

which increased by about $ 3 3 billion in 1990-91. About 63 p e r c e n t of the i n f l o w in 1990 was matched

by

an increase in official reserves, leaving the remaining 37 percent to finance the deficit in the current account. Y e t , the latter increased markedly in 1991, accounting f o x 55 percent of the c a p i t a linflow.

considering 1990-91 as a whole, the net c a p i t a l inflow wasequally split into a widening in the current account d e f i c i t (a reduction in CA) and an increase in o f f i c i a l reserves (a reduction tn R A ) . The former suggests that c a p i t a l inflows have been assoctated with

an

increase in the gap between national investment and national saving. In countries like Chile and Mexico,an

important part of the i n f l o w s has financed increasesin

private investment; y e t , in countries like Argentina and Brazil there has been a marked risein

private consumption.2/

The increasein

o f f i c i a lreserves, in turn, indicates that the capital inflow was met with a rather

heavy degree of f o r e i g n exchange market Lntervention by the various monetary

authorities.

Part

of

t h e increased c a p i t a l inflows represent repatriationof

previous flight capital (whose s t o c k abroad Is estimated at about

$200

b i l l i o n at the endof

the1980s).

3

J

But, there also are new investorsin

Latin America. Table 2 reports various items fn the c a p i t a l account of Latin America. Notice t h a t quantitatively the most important item is the increasein

net external borrowing, which accounts f o r 70 percentof

the

capital inflow in 1990-91, and which is primarily borrowing by the p r i v a t eFor the purposes of the present section, Latin America includes the

same s e t of countries included under Western Hemisphere in

IMF's

WorldEconomic Outlook and

International

Financial

S t a t i s t i c s . 2J These figures, which are available

from

the authors, expressinvestment and consumption as shares of GDP and

rely

on

preliminary national

income accounts data f o r

1991.

Table

2.

Latin

America:

Items

in

the

Capital

Account

(In biljimsof

U.S.doltars)

Net external Nm-debt Asset

tranmions

Errors andYear borrowing creating flows (net) I / ommissions 1 f Total

1973 6.0 2.5

--

--

8.51974 11.7 2.2

--

--

13.31975

11.4

3.3--

--

14.71976 14.2 2.7

--

--

16.91977

19.4

2.8 -2,5 -3.4 16,41 978

28.0

4.9 -2.5 -3.1 27.41 979 30.2 7.2 -2.4 -2.1 32.9

1980 43.1 6.8 -3.0

-

13.0 34.01981 61 -0 8.2 -8.9

-

17.5 41.91982 45.7 7.2 -7.7 -22.1 23.0

1983 18.7 4.6 -10.9 -8.8 13.6

1984 14.1 4.5 -3.1 -3.0 12.5

1985 6.2 6.1 -5.4 -1.4 5.5

1986 11.3 4.3 -1.3 -1.9 12.3

1987 10.0 6.0 -1.2 0,s 15.3

1988 3,8 8.8 -4.3 -3.5 4.7

1989 10.9 6.9 -2.1 -3.6 12.1

1990 28.0 8.6

-

12.5 -0.2 23.91991 f

7.3

14.9 6.7 1.7 39.8Swrce: Data for western hemisphere, World Ecmomc Outlook, IMF, various

issues.

11 These two categories

are

included innet

external

borrowing and mn-debt creating flows from [image:14.612.71.519.156.485.2]sector from foreign private banks.

U

Increased external borrowingreflects the restoration of access to voluntary c a p i t a l market flnancfng

after the debt crisis--a restoratfon that follows a period of s i x years

during which voluntary Loan and bond financing flows to Latin America were severely limited. 2J

In

addition to greater domestic borrowing abroad,there were increases

in

p o r t f o l i o knvestment and foreign direct investment. The latter amounted to about $12 billion, $4 b i l l i o n of which was the result of privatizations.Since there has been a substantial degree of central bank intervention

in the face of capital inflows, there is an important degree of comovement

between o f f i c i a l reserves and capftal inflows.

In

fact,if

one isinterested

in

monthly developments, for which direct data on capital inflows are n o t available, changes fn reserves are a reasanable proxy f o r theseinflows,

Chart

2,which

d e p i c t smonthly

data on o f f i c i a l internationalreserves for the countries in our sample, shows t h a t for most of the countries, there is a pronounced upward trend

in

the stock of officialreserves starting from about the first half

of

1990. In 1991, the year w i t hthe hfghest c a p i t a l inflows to the region, reserves accumulation accelerated as

the

monetary authoritkesin

most countries reacted to the c a p i t a l inflowsby

actively increasing t h e i r purchases of foreign assets constitutinginternational reserves. Brazil and Uruguay are exceptions to t h i s pattern,

as in both countries, capital inflows w e r e not accompanied by an increase In

reserves.

2. Real e x c h a n ~ e rate a t e

Chart

3 provides evidence onthe

behaviorof

the real effective exchange rates. 3J A t least t w o regularities emerge from t h i sfigure:

( I )

with t h e exceptionof

Brazil, a l l countries are experiencing a realexchange rate appreciation since January of 1991. In h a l f of

the

cases the real appreciation a £ the domestic currency began before January1991;

and ( 2 ) even w5thin a small sample of monthly observations covering four years,there

is considerable evidence a£ cyclical behaviorof real

exchange rates.Leading examples of this phenomenon are Brazil,

Chile,

and Uruguay.While

some of these cycles can be attributed to fluctuationsin

capital inflows, they are also the r e s u l t of other shacks such as fluctuations in the termsof

trade andin

domestic monetary, f i s c a l , and exchange rate policies.Combining the evidence from Charts 2 and 3 indicates t h a t there

is an

important degree of comovement in these variables across countries, desptte thewide

differences in policiesand

institutions among them.We

v i e w t h i s comovement as compatible w i t h the notion t h a tthere

is a common shock t h a tSame

of

t h i s increased borrowingmay

represent hidden repatriationof

flight c a p i t a l ,2

J See, for instance, El-Erian

(1992)

and International Monetary Fund(December 1991. Chapter 111).

Chart

2.

TOTAL

RESERVES

MINUS GOLD

Billions of U.S. dollarsBRAZIL

"

7

7

0 1 ) , BOLIVIA

Y O , CHILE 1

ECUADOR

1 , --I

09 3

on -

o r -

RE

-

as -

IU

-

O J -

0 2 4 h-

vy

m.

h M.

MID.

h m.

Urn.

h 9 1.

U U.

h a p.

VENEZUELA

Chart

3.

REAL

EFFECTIVE EXCHANGE

RATE

4 0 BRAZIL

4 0 4 7

I S

4 0

4. 4 1

- Y a s - Y a h o c r & m . h O l d a i

URUGUAY

'.

7

-*-IYI - CHILE

4- '

4 a -

4 M - 4m

-

* w -

ECUADOR *m

am

a w

3 M

a-

*&?

1 8

am

*'M

-

a74 '

a n

-

3 1 - am

-

383

-

3 w .

3- 4

> a . . . . . . .. . .

Source: Information Notice System, IMF.

a f f e c t e d the whole region and resulted

i n

increased c a p i t a linflows

and realexchange rate appreciation.

3. Rates

of

return d i f f e r e n t i a l sExpected rates of return en available assets across cauntrfes

play

akey

rolein

investors' decisfonson

whetheror

not to move capttalinternationally. Since data

for

expected returns are notread5ly available,

and depend on how one models expectations, we first look at the stylized

facts in

the

farm of e x post returns ( s e e Charts 4 and 5).As shown in Chart 4 ,

there

was a large increasein

the

U.S. d o l l a rstock prices of major Latin American markets i n 1991. Argentina exhibits

the biggest s i n g l e annual return of almost 400 percent, while Chfle and

Mexico registered returns of about 100 percent each.

l

J

According to the"emerging markets" data from IFC, investments

in

Latin American securitiesy i e l d e d total returns of

134

percent in dollar termsin

1991.,These

s t o c kmarket booms are associated w i t h increased

purchases by

Latin Americaninvestors as well as by foreigners. The marked increases

in

s t o c k marketprices have resulted in skmflar rises %n the prices of country and regional

market funds traded in the United States and elsewhere. Along w i t h these price developments, there has been a maxked x i s e

in

market capitalizationof

Latin American equity markets

in 1991.

Overall market capitalization inArgentina rose from $ 3 . 3 b i l l i o n

in

1990 to $18.5billion

i n

1991; in

Brazilit rose from $16.4 billion in 1990 to $ 4 2 . 8 billion in 1991;

in

Chile from$13.7 billion

in 1990 to $28 billionin

1991; andin

Mexico it rose from$ 3 2 . 7 b i l l t o n in 1990 to $101.2 billion in 1991. 2J According to Salomon Brothers, $850 b i l l i o n of f o r e i g n investment entered

Brazil's

stock marketin

t h e last four months of 1991, and about$600 million

was invested by foreigners in t h e Argentineequity

marketin 1991.

3

J

However, as thefigures indicate and Chart 4 confirms, the s t a c k market booms and the

attendant

high

returns appear to materialize after c a p i t a lhas

begun toflow

in

to the region. It wouldthus

be

d i f f i c u l t to argue that high stockmarket return differentials

were

responsible for a t t r a c t i n g the f i r s twave

of c a p i t a l i n f l o w s .Chart 5 provides evidence on the

lending

and deposit interest ratespreads between U.S.

dollar

equivalent domestic i n t e r e s t rates and interestrates in the United S t a t e s . Since kn some

of

these countries interest ratesare regulated, and since c a p i t a l m o b i l i t y

is

f a r

from free,

spreads acrossthe various countries cannot be compared in a straightforward manner. In

The price/earnings ratio

in

Argentina increasedfrom 3.1 in 1990:IV

to3 8 . 9 in

1991:IV;

in Chile

it increasedfrom

8 . 9in 1990:IV

to17.4

in

1991:IV; and in Mexico it moved from 1 3 . 2 in 1990:IV to 14.6 In 1991:IV.These figures are from Emerging Markets Data Base, International Finance

Corporation.

2

J These figures are

from

P

g

,

Fourth Quarter 1991, International Finance Corporation.

addition, as Chart 6 h i g h l i g h t s , the

variability

in domestic i n t e r e s t ratesvaries markedly across countries.

To

accommodate t h i s featurethe

scales inChart

4

vary from country tocountry,

wkth Argentina andPeru

having

thebroadest ranges and Bolivia and Colombia the narrowest. With these caveats

in

mind, the dominant impressionfrom

Chart 5 i s that ofrelatively

high

interest d i f f e r e n t i a l s in L a t i n America in the 1990-91 p e r i o d . It is also evidentfrom

Chart 5 t h a t the pattern of spreads varies considerably acrosscountries.

In

e f f e c t , t h i s is n o t surprising since the monetary authoritiesin

these countries have n o t reactedin

a uniform manner to the capitalinflows and

the

timingof

regulatory changes has also varied considerablyacross the countries considered.

While

the

relativelyhigh

differential rate of return on L a t h Americana s s e t s has been associated w i t h a marked rise

in

c a p i t a l inflows to the region,the

inflows have not arbitraged awaythe

large differentials. Insome countries, such as Argentina, the interest rate differential decreased

sharply as capital poured in; yet in others, such as Chile, there was a less

pronounced response of t h e interest rate differential to the

inflows

(seeChart 5). As argued

in

SectionV ,

these different patterns may r e f l e c tcross-country differences

in

the authorities' choices between s t e r i l i z e d andnonstexilized intervention. In any case, it should

be

stressed that some ofthe relatively

high

observed differentials may be due to the f a c t that theyare measured here ex post, as opposed to ex ante which is the one that is relevant for investor's decisions. I n particular, as in a "Peso problem," s i z a b l e discrepancies between ex ante and ex post returns could

be

accountedfor by the fact that investors assigned a non-negligible

probability

thatLatin American reforms could collapse, that capital controls could

be

re-imposed, that there could be large devaluations against the dollar,

or

thatinterest rates in t h e United States could sharply rise.

Y e t , even

if

there were d i r e c t data on expected, or ex ante, rates ofreturn differentials, we suspect t h a t these c o u l d

well

show substantialpersistence

over

time due to the existenceof

financial andexchange

raterisk. In fact, Chart 6 illustrates for both debt and equity instruments how

in

countries t h a t provided h i g h ex p a s t returns one also observes arelatively

high variance of these returns. In addition, differentials maypersist due to high transactions costs and information costs

I/,

c a p i t a lcontrols, and country transfer (or political) risk. However, whether the

observed differentials reflect these fundamental factors or are due ta a

financial

bubble is y e t to be determined.In

sum, three main s t y l i z e d f a c t semerge

with regard to i n t e r e s t ratedifferentials. F i r s t , there is little comovement in domestic i n t e r e s t rates

-

I/

Someof

the factorsthat

make f t d i f f i c u l t f o r foreign investors to-

invest in several Latin American markets are: the lack of full financial

information about various traded companies, the absence

of

a comprehensives e t

of

insider trading regulations and of strictbroker

requirements in somecases, and the difficulties

in

dealing with standard accounting practicesC h a r t

4.

S T O C K

M A R K E T P E R F O R M A N C E

(Stock Price

Indices In

U.S.

Dollars, January 1988= 100)P!ote T h c S 8 P 5 0 0 ~ n d e l r w a s u s e d t o r t h c U n ~ t e d S t a t e s

S o u r c e s : S t a n d a r d E P o o r ' s a n d I n t c r n a l n o n a l f ~ n a n c c C o r p o r a t i o n . O u a r f c r l y R e v i e w o f

Chart

5.

INTEREST

RATE SPREADS

(DaHsr Equivalent d Domestic Rate less U.S. Rate. Annual Rates)

BRAZIL

-

:

U R U G U A Y

,,

,-

--

- .- - - . . . - - 11m. CHILE

E C U A D O R

I

1

I

any urn CIW MU CI# urn b m u r m m

P E R U

Lsrxkops-

\

m V E N E Z U E L A

S o u r c e : International Financial S t a t i s t i c s a n d v a r i o u s C e n i r a l Bank bulletins.

C h a r t

6 .

R I S K

A N D R E T U R N S

Credit

Markets:

Lending

Rates of

intersst

A v e r a g e M o n t h l y R e t u r n i n U . S . D o l l a r s

0 . 0 4 0

Argentina

-

-

a U r u g u a y

-

-

a M e x i c o Paru aQ Chile

Bolivia Braxil

-

-=u;S~a\arn bia V e n e z u e l a

-

E c u a d o r

e

S t a n d a r d D e v i a t i o n

Selected

Stock

Markets

0

0 . 0 2 0 . 0 6 0.1 0 . 1 4 0 . 1 8 0 . 2 2 0 . 2 6 0 . 3

S t a n d a r d D e v i a t i o n A v e r a g e M o n l h l y R e t u r n i n V . S . D o l l a r s

S o u r c e s : I n t e r n a t i a n al F i n a n c i a l S t a t i s t i c s , v a r i o u s C e n t c s l B a n k B u l l e t i n s , I F C O u a r t e r l y R e v i e w o f E m e r g i n g S t o c k M a r k e l s , a n d S t a n d a r d & P o o r s .

0 . 0 5

0 . 0 4

-

4.03

-

0.02 -

Argentine u

M e x i c o

0 Chile

V e n e z u e l a

P B razilp

a

C o l o m b i a

(in U.S.

dollars),

and hence in spreads, across t h e countriesin

our

sample.Second, the "noise-to-signal ratio" of the domestic dollar rates varies

substantially across countries. As Chart 6 illustrates based on

ex

postd a t a , countries o f f e r i n g t h e highest returns also had the greatest

volatility of returns. Third, d e s p i t e s i z a b l e capital inflows

the

positive differentials have not been f u l l y arbitraged away. The persistence and s i z e of thts wedge between domestic and f o r e i g n rates also appears to

vary markedly across countries,

4 . Other macroeconomic develovments

Selected macroeconomic developments are reported in Table 3 . Consider

how developments

in

1991--theyear

when c a p i t a l inflows grew to about$40 billion--differ from e a r l i e r years. First, t h e r e was n renewal of economic growth. A f t e r three years of s t a g n a t i o n , real GDP increased by

almost 3 percent in 1991. However, gross capital formation as perceht of

GDP

remained constant at about t h e same level of the second half of the1980s suggesting a more efficient utilization of xesouxces. A t the same

time, there was a marked drop

in

the

sate of in£ lation (which nevertheless remained at a three-digit level f o r t h e r e g i o n ) , and a significant reduction in central government fiscal d e f i c i t s .The changfng economic conditions in Latin America are also reflected

in

the region's debt and solvency indicators. A t $441 billion, external debt amounts to 2.6 times exports of goods and services. Although still high,

this ratio has decreased markedly from the 3.5 figure in 1986. Since m o s t

o f Latin America's external debt ta comercial banks is still in terms of floating r a t e s , the drop

in

shorr tern U . S . i n t e r e s t rates and the drop in the debt to exports ratio has translated into a sapid decline in theexternal debt service ratio over the last two years. In f a c t , the level of

the

debt service ratio in 1991 ( i . e . , 32.8 percent) isof

the same orderof

magnitude as the levels observed before the previous c a p i t a l inflow episodeof 1978-81. As indicated above, capital inflows have been associated

with

r a p i d accumulation of international reserves, which reached t h e record figure of $ 65.3 billion in 1991. As shown

in

Table 3 , the r a t i o of reserves to irnporca was 33.5 in 1991, which is of a similar order ofmagnitude as

in 1 9 7 7 - 7 8 .

These developments represent only part of the changing economic

environment

in

Latin America of the early 1990s.In

addition to these, the move toward privatization and deregulation, the introduction of financial reforms, and the restructuringo f

existing external debt have a l lcontributed to

bringing

Latin America back on the List ofviable

investmentlocations

in

world financial markets.Unfortunately,

the fact that severalsf these variables could n o t be quantified prevented us from including them

in the econometric analysis of the n e x t s e c t i o n .

It

is useful te compare the present episode of c a p i t a l i n f l o w s w i t h earlier similar episodes.I

J

The previous capital inflows episodeoccurred from

1978

to 1982, and was the precursor of the ensuing debtcrisis.

However,

the datain

Tables 1 to 3highlight

important differencesacross these t w o episodes. First, the capital inflows o b s e r v e b t h u s f a r i n 1 9 9 0 - 9 1 are much smaller than

in

1 9 7 8 - 8 2 .In

particular, c a p i t a l inflowsbetween $45

billion

and $50 billion were observed in each one of the threeyears 1980-82. This difference becomes larger i f one compares the c a p i t a l

inflows as a percentage of GDP; while capital inflows in 1978-82 represented

7

percent o f GPP at t h a t t i m e , the capital inflows in 1991 are in the order of 4 percent of GDP f o r t h a t year. Y e t , the difference would probably become smaller if changes in capitalflight

are

taken i n t o account. Whilein the earlier episode capital flight was increasing in m o s t countries along with increased (reported) capital inflows, in the present episode capital

inflows appear to be accompanied by a decrease in the stock of flight c a p i t a l for these countries.

Second, these t w o episodes differ in how

the

capital inflows arematched by changes in the other accounts of the balance of payments. While

t h e present c a p i t a l inflows are accompanied

by

approximately equal increasesLn the current account d e f i c i t and

in

o f f i c i a l reserves, the l a t t e r played arelatively

minorrole

in

the 1 9 7 8 - 8 2 episode. That is, most capital inflows in1978-82

financedhigh

current account d e f i c i t s , with the monetaryauthorities playing a less a c t i v e role, Notice t h a t the current account

d e f i c i t peaked

in

1981 at 5 . 5 percent of G D P , while the d e f i c i t i n 1991 is about2

percent o f GDP. The combination of smaller current account deficits and t h e marked increase in o f f i c i a l reserves in1990-91

indicates t h a tduring the present episode t h e r e is less of a decline in Latin America's net

foreign wealth than

in

theearlier

episode and that there is more of acushion against adverse shocks to capital flows in future p e r i o d s .

2/

The

heavier degree of o f f i c i a l intervention in forefgn exchange markets in thepresent episode may reflect the authorities' objectives t o bring actual reserves-to-imports ratios

back

to their desired levelsand/or

to meetincreases in t h e nominal demand for money with foreign-reserves-backed

monetization.

Third, the set

of underlying

macroeconomic condkrions and t h ebehavior

of fundamentals are now different from those in 1978-82 (Table 3 ) . In thee a r l i e r e p i s o d e inflation rates were increasing, as were government budget

d e f i c i t s , and at the same time real GPP was growing at about 5 percent a

1/

I n fact, such comparisons arethe

subject of a separate research-

p r o j e c t t h e authors are preparing.

2/ Notice, however, t h a t t h e burden of foreign debt was larger at

the

-

year.

In

the present circumstances, inflation isfalling,

although i t is still h i g h , and governments are balancing their previous d e f i c i t s . At the same time, there is now a recovery of growth in the reglon, which in the prevtousthree

years had b a s i c a l l y disappeared.B e s i d e s these d i f f e r e n c e s , there are many simhlarities in the t w o episodes: accumulation of international reserves, real exchange rate

appreciation, boornrng stock markets, and h i g h differentials between domestic and foreign rates of return. The similarity e x h i b i t e d

by

the behavior of s t o c k markets then and now 5 s striking. In 1979, s t o c k prices in dollarterms rose

by

234 percent in Argentina, while inChile

they roseby

116

percent andin

Mextco by 63 percent--magnitudes in line w i t h the experience in 1991.While more d i f f i c u l t to document, another important episode of c a p i t a l inflows to Latin America occurred in t h e 1920s, when the investment climate seemed reasonabLy good. As Diaz Alejandro (1983) n o t e s , before World War

I

portfolio and direct investment i n L a t i n America originated mainly i nEurope. However, the 1920s were dominated by c a p i t a l inflows from the

United S t a t e s , while investments from Europe markedly slowed down. In

p a r t i c u l a r , there was a pronounced expansion of public borrowing in the New

York market at that time. Diaz Alejandro (1983) provides evidence of

sizable investments

by

Britain and t h eUnited

Statesin

Argentina,Chile,

Cuba, and Mexico. Toward the end of the 1920s, these t w o major foreign investors had accumulated a stock of claims in Latin America of around fourtimes the value of

annual

merchandise exports in thatregion.

J

I

An

importantlesson from

these episodes isthat

the c a p i t a l inflowswere eventually reversed in what turned out to be major crises.

During

the debt crisis of the mid 1980s, capital inflows to Latin America were reducedto about 20 percent of their earlier values, P u t differently, the total

amount of

voluntary

loan and bond financing flowing t o Latin Americancountrkes during t h e entire 1983-88 period was considerably smaller t h a t f o r

1982

alone. As access to fnternational credit marketswas

curtailed and

thecapital account surplus dwindled, a sharp reduction

in

current account deficits became necessary,In the 1920s-30s episode, external factors resulted

in

a sharp fall inc a p i t a l inflows to L t i n America

toward the

end of the1920s, well

beforesome of the countries

in

theregion

began having difficulties servicingt h e i r external d e b t s . Foreign capital

markets

d r i e dup in the 1930s. While

the increased burden of debt servicing in the c r i s i s of the 1980s came via higher interest r a t e s , during the c r i s i s of the1930s

it came through a fallfn the dollar price level which led to a marked increase i n the real burden

o f debt servicing. It is at t h i s p o i n t that most countries suspended normal

Thus, assuming a 5 percent rate of return