This is a repository copy of

Multimodal Choice Modelling – Some Relevant Issues.

.

White Rose Research Online URL for this paper:

http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/2395/

Monograph:

Ortuzar, J. de D. (1980) Multimodal Choice Modelling – Some Relevant Issues. Working

Paper. Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds , Leeds, UK.

Working Paper 138

eprints@whiterose.ac.uk https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/

Reuse

Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website.

Takedown

If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by

White Rose Research Online

http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/

Institute of Transport Studies

University of Leeds

This is an ITS Working Paper produced and published by the University of

Leeds. ITS Working Papers are intended to provide information and encourage

discussion on a topic in advance of formal publication. They represent only the

views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views or approval of the

sponsors.

White Rose Repository URL for this paper:

http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/

2395/

Published paper

Ortuzar, J. de D. (1980)

Multimodal Choice Modelling – Some Relevant Issues.

Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds, Working Paper 138

ABSTRACT

ORTUZAR, J. de D. (1980) MultimodaL choice modelling

-

some r e l e v a n t i s s u e s . Leeds: University o f Leeds,Inst.

Transp. Stud., WP 138. (unpublished)This paper g i v e s an overview of t h e most r e l e v a n t

i s s u e s r e l a t i n g t o t h e a p p l i c a t i o n of multimodal choice

models ranging from d a t a c o n s i d e r a t i o n s , such a s a l t e r n a t i v e

sampling s t r a t e g i e s and measurement techniques, t o t h e h o t l y

debated aggregation i s s u e . P a r t i c u l a r emphasis i s placed on

t h e s p e c i f i c a t i o n and e s t i m a t i o n problems o f disaggregate

choice models.

D r . Ortuzar's address i s : Departamento de I n g e n i e r i a de Transporte Universidad C a t o l i c a de Chile

C a s i l l a

114-D

CONTENTS

Abstract

1. I n t r o d u c t i o n

2. The problem of aggregation

3. Data c o l l e c t i o n and measurement

3 . 1 Representation and measurement of t r a v e l a t t r i b u t e s 3.2 A l t e r n a t i v e sampling s t r a t e g i e s

4;

Model s p e c i f i c a t i o n4 . 1

Model s e l e c t i o n4.2 Choice s e t determination

4 . 3 Defining t h e form of t h e u t i l i t y function

4 . 4

Model s t r u c t u r e and v a r i a b l e s e l e c t i o n5.

Model estimation5.1 General statement of t h e problem

5.2

Maximum

l i k e l i h o o d estimation and a l l i e d s t a t i s t i c a l t e s t s5.3 Model comparison through goodness-of-fit measures

5.4

Validation samples5.5 Comparison of non-nested models

5.6

Estimation of models from choice-based samples5.7

Estimation of h i e r a r c h i c a l l o g i t models AcknowledgementsFigures

M U L T I M O D A L C H O I C E M O D E L L I N G

-

SOME R E L E V A N T ISSUES1. INTRODUCTION

The problems of mode choice modelling and f o r e c a s t i n g have been

approached i n many ways s i n c e t h e mid-50s, but f o r t h e most p a r t ,

research and a p p l i c a t i o n s have been concerned with choice between c a r

and public t r a n s p o r t which, it has been argued, i s t h e s i t u a t i o n faced by t h e m a j o r i t y of t r a v e l l e r s i n t h e journey-to-work. However, it i s obvious t h a t people do not n e c e s s a r i l y choose between two s p e c i f i c

a l t e r n a t i v e s only when making t h e i r choice, but i n s t e a d t h e y g e n e r a l l y

confront options such a s d r i v i n g a c a r , t r a v e l l i n g a s passengers i n a

c a r , bus o r t r a i n , r i d i n g a b i c y c l e o r a s c o o t e r o r simply walking. I n

a d d i t i o n , each t r i p might u t i l i s e a combination of modes, i . e . mixed-

mode t r i p s ( f o r example, park-and-ride), although it can be argued t h a t some mixed options a r e so u n l i k e l y t h a t t h e p r o b a b i l i t y of t h e i r

s e l e c t i o n can be considered a s zero. A s a consequence, it has often

been s u g g e s t e d t h a t i n d i v i d u a l s can be considered a s u s e r s of t h e i r

'main mode' (e.g. t h e procedure used i n t h e majority of t r a n s p o r t a t i o n

s t u d i e s i n t h e U.K. )

.

However, t h i s procedure i s c l e a r l y i n a c c u r a t e f o r many people who depend on another mode f o r access t o t h e major one.Also, with t h e i n c r e a s i n g departure from t r a d i t i o n a l p o l i c i e s based on

a 'pure' mode context and t h e emphasis on an ' i n t e g r a t e d ' approach t o

urban t r a n s p o r t problems, t h e time i s r i p e f o r models which a r e more

o r i e n t e d towards a l t e r n a t i v e p o l i c i e s , such a s p r i c e penalty measures,

t r a f f i c r e s t r a i n t and exclusion schemes, bus p r i o r i t y measures,

i n c e n t i v e s t o park-and-ride and car-pooling, e t c . , and which must be

multimodal ( a s opposed t o b i n a r y ) i n n a t u r e .

During t h e l a s t decade, and p a r t i c u l a r l y over t h e l a s t f i v e y e a r s ,

s i g n i f i c a n t advances have been made i n t r a v e l demand f o r e c a s t i n g

methods. The most important and widely promoted new techniques have

been t h e so-called 'disaggregate' o r 'individual-choice' o r 'second

generation' models ( f o r a good review of t h e o r e t i c a l developments, see

Williams, 1979). These models have been u s u a l l y generated w i t h i n a

'random u t i l i t y ' t h e o r y framework(*) ( f o r a review, s e e Domencich and

-. .

( * ) Note t h a t t h e t h e o r y i s not constrained t o disaggregate models only;

McFadden, 1975). I n t h i s quanta1 choice theory, t h e decision-maker i s

assumed t o choose t h e option ( A . ) which possesses, a s f a r a s he i s

J

concerned, t h e g r e a t e s t u t i l i t y U . . I n order t o account f o r d i s p e r s i o n

J

-

t h e f a c t t h a t i n d i v i d u a l s with t h e same observable c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s do not n e c e s s a r i l y s e l e c t t h e same option-

t h e modeller introducesa random element e i n a d d i t i o n t o each measured i n d i v i d u a l ' s u t i l i t y

-

jU..

I n t h i s way, t h e u t i l i t y of a l t e r n a t i v e A . i s a c t u a l l y representedJ J

as:

Ortuzar and Williams (1978) have described pedagogically, t h e

generation of random u t i l i t y models, ranging from t h e very convenient

but t h e o r e t i c a l l y r e s t r i c t i v e multinomial l o g i t (MNL) model, t o t h e

general and powerful but r a t h e r i n t r a c t a b l e multinomial p r o b i t ( M N P )

model.

I n t h i s paper we wish t o discuss b r i e f l y some i s s u e s r e l a t e d t o

t h e a p p l i c a t i o n o f such models (and i n some cases any model) t o t h e

problem of choice of mode f o r t h e journey-to-work. We w i l l consider questions of d a t a , such a s t y p e of data, a l t e r n a t i v e sampling s t r a t e g i e s

and problems of measurement, and modelling i s s u e s , such a s model

s p e c i f i c a t i o n and estimation. However, we

w i l l

f i r s t address t h e aggregation problem which l i e s a t t h e h e a r t of one of t o d a y ' s mosth o t l y contested debates

-

whether t o use aggregate o r disaggregatemodels, and i n which circumstances.

We do not attempt t o be comprehensive on t h e s e i s s u e s , so we

r e f e r t h e reader t o good general discussions by McFadden (1976; 1979a);

Williams (1977; 1979); Hensher (1979a); Ben-Akiva e t a1 (1977; 1979);

Daganzo (1980) ; Daly (1979) ; Jansen e t a l (1979) ; Wnheim (1979) ;

Reid (1977) ; Spear (1977; 1979) ; and Williams and Ortuzar (1980b).

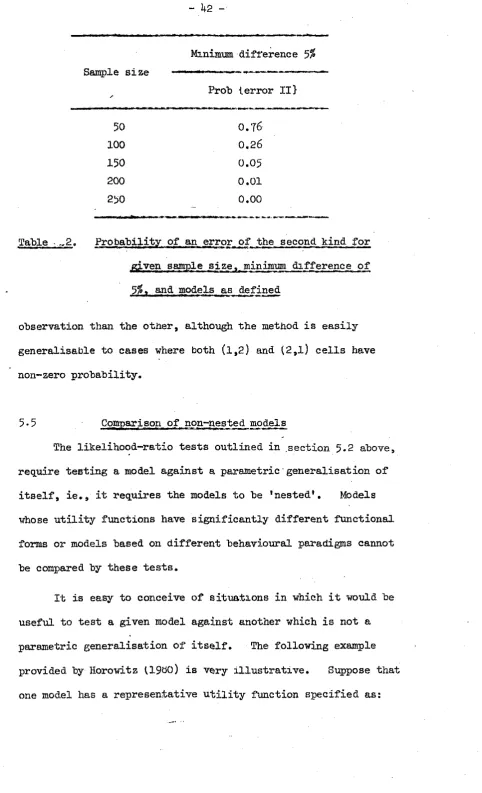

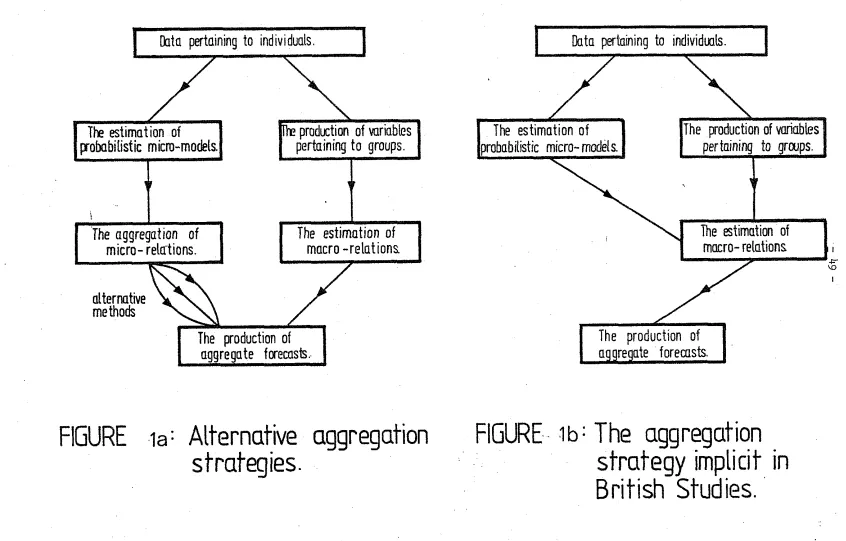

2. THE PROBLEM OF AGGREGATION

The aggregation i s s u e may be thought of i n very general terIUS a s

t h e path through which a d e t a i l e d d e s c r i p t i o n of an i n d i u i d u a l ' s

decision-making process, a s imputed by a modeller, i s transformed i n t o

a s e t of observable e n t i t i e s and f o r r e l a t i o n s which can be u s e f u l l y

employed by him. I n an econometric i n t e r p r e t a t i o n of ( t r a n s p o r t demand)

models, t h e aggregation ovsr

unobservabZe entities r e s u l t s i n

a

p r o b a b i l i s t i c d e c i s i o n ( c h o i c e ) micro model, and t h e aggregation over

aggregate o r macro r e l a t i o n s . I n t h i s sense, t h e d i f f i c u l t y of t h e

aggregation problem depends, t o a l a r g e e x t e n t , on how t h e components

of a system a r e described within t h e frame of r e f e r e n c e used by a

modeller, because it i s p r e c i s e l y t h i s framework which w i l l determine

(*I

t h e degree of v a r i a b i l i t y t o be accounted f o r i n a ' c a u s a l ' r e l a t i o n .To give an example, if t h e frame of reference used by a modeller i s , say, t h a t provided by t h e entropy maximising approach, t h e explanation

of t h e s t a t i s t i c a l d i s p e r s i o n i n a given d a t a s e t w i l l be very d i f f e r e n t

t o t h a t provided by another observer using a random u t i l i t y maximising

approach, even i f t h e y both f i n i s h up with

identicaz model functions

( t h e e q u i - f i n a l i t y i s s u e , s e e , f o r example, Williams, 1979). The

i n t e r p r e t a t i o n of such a model, say t h e c l a s s i c i a l

MNL,

depends howeveron t h e theory used t o generate i t , and t h i s i s p a r t i c u l a r l y important f o r i t s e l a s t i c i t y parameters. For t h e entropy maximising modeller,

t h e parameter corresponds t o a Lagrange m u l t i p l i e r a s s o c i a t e d

' I . . .

with the change i n ZikeZihood of observing a given

aZZocation (share) pattern

...

with respect t o incrementaZ

changes i n system

t r i pcost measures".

(WiZZiams,

2 9 7 9 )For t h e second modeller, t h e same parameter i s now i n v e r s e l y r e l a t e d

t o t h e standard d e v i a t i o n of t h e u t i l i t y d i s t r i b u t i o n s from which t h e

model i s generated (**) s e e ~ i l l i a m s (1.977).

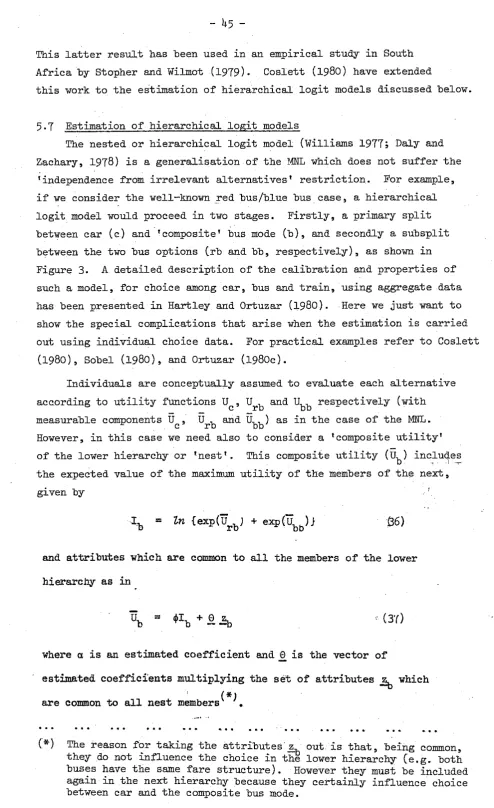

I f we choose t o use a random u t i l i t y approach, t h e aggregation

problem w i l l reduce, t o o b t a i n from d a t a , a t t h e l e v e l of t h e i n d i v i d u a l , aggregate measures such a s market shares of d i f f e r e n t modes, flows on

l i n k s , e t c . , which a r e t y p i c a l f i n a l model outputs. There a r e two

obvious ways of proceeding, a s shown i n Figure l ( a ) , which a r e b a s i c a l l y

d i s t i n g u i s h e d by having t h e process of aggregating i n d i v i d u a l d a t a

before

o ra f t e r

model e s t i m a t i o n . I f t h e data i s grouped p r i o r t o t h eestimation of t h e model, we w i l l have t h e c l a s s i c a l ' a g g r e g a t e b p p r o a c h

which has been h e a v i l y c r i t i c i s e d f o r being i n e f f i c i e n t i n t h e use of data (because data i s aggregated, each observation i s not used a s a data p o i n t and t h e r e f o r e more d a t a i s needed), f o r not accounting f o r

(*l

I am g r a t e f u l t o Huw Williams f o r having explained t h i s i n t e r p r e t a t i o n t o me.(**I

Two comments a r e worthwhil e here: f i r s t l y t h e f u l l i n t e r p r e t a t i o n of model parameters is-not t r a n s f e r a b l e within t h e o r i e s ; and, secondly, while i n some cases t h e i n t e r p r e t a t i o n might not m a t t e r( i . e . i f one i s i n t e r e s t e d on flows i n networks) i n o t h e r s it can be very c r u c i a l , f o r example, if we a r e seeking t o endow p r e d i c t e d

t h e full v a r i a b i l i t y i n t h e d a t a (e.g. within zone variance may be

<

higher than iner-zonal v a r i a n c e ) , and f o r r i s k i n g s t a t i s t i c a l

d i s t o r t i o n and b i a s (such a s t h e wgll-known e c o l o g i c a l f a l l a c y ) , e t c .

The 'disaggregate' approach, on t h e o t h e r hand, e s t i m a t e s t h e model a t

t h e l e v e l of t h e i n d i v i d u a l t h u s apparently answering, a t t h i s s t a g e ,

t h e c r i t i c i s m s mentioned above. The question t h a t remains, however,

i s how t o perform t h e aggregation operation over t h e micro r e l a t i o n s ?

As we w i l l see below, t h e answer i s

...

' r a t h e r simply',if

we a r e i n t e r e s t e d i n short-term p r e d i c t i o n s of journey-to-work mode choicemodels; however, f o r o t h e r modelling requirements, t h e answer ranges

from

...

' d i f f i c u l t ' , t o...

'almost impossible', u n l e s s being self-defeating i n t h e sense of r e q u i r i n g h e r o i c assumptions ( a s bad a st h o s e c r i t i c i s e d i n t h e 'aggregate' approach) and/or enormous amounts

of e x t r a d a t a . I n f a c t , Reid (1977) i n t h e context of developing a

disaggregate model system has remarked t h a t

"

...

t h e r e a r e p r a c t i c a l and t h e o r e t i c a l l i m i t s t o t h e a p p l i c a t i o n of s t r i c t l y behavioural methods...

it i sd i f f i c u l t t o preserve a behavioural s t r u c t u r e and conform t o aggregate observations..."

Before b r i e f l y describing t h e main aggregation methods, l e t u s

note t h a t t h e approach followed i n B r i t i s h p r a c t i c e i s a hybrid o f t h e

two mentioned above a s shown i n Figure l ( b ) . For example, household

based ( r a t h e r t h a n zonal) category a n a l y s i s has been used a t t h e t r i p

generation s t a g e , while t h e SELNEC and subsequent s t u d i e s used

weighting c o e f f i c i e n t s obtained from a standard disaggregate study

(e.g. McIntosh and Quarmby, 1970), i n a g e n e r a l i s e d c o s t formulation.

However, t h e e l a s t i c i t y parameters (e.g. p and

A )

and o t h e r model constants have been determined from an aggregate c a l i b r a t i o n . This' t r a n s f e r a b i l i t y ' of micro parameters ( * ) between d i f f e r e n t s t u d i e s

(e.g. d i f f e r e n t regions and d i f f e r e n t times) w i t h t h e p o s s i b i l i t y

of l o c a l ' t u n i n g ' (Goodwin, 1978) may be seen a s a pragmatic approach

t o t h e aggregation problem. This i s s u e i s discussed a t more l e n g t h

by Williams and Ortuzar (1980b).

('1

Which i n t e r e s t i n g l y bears c l o s e analogy t o t h e s t r a t e g y proposed by Ben-Akiva C19791 f o r t h e t r a n s f e r a b i l i t y of disaggregate models, although with d i f f e r e n t motivations.Returning t o t h e general approaches shown i n Figure l a , much

research has been d i r e c t e d r e c e n t l y a t a comparative a s s e s ~ m e n t of

aggregation methods ( s e e , f o r example, Ben-Akiva and Atherton, 1977;

Ben-Akiva and Koppelman, 1974 ; Bouthelier and Daganzo, 1979 ; Daly

,

1976; Dehghani and T a l v i t i e , 1979 ; Hasan, 1977; Koppelman, 1974,1976a, 1976b; Liou e t a l , 1975; McFadden and Reid, 1975; Meyburg

and Stopher, 1975; .Miller, 1974; Reid, 1978a, 19781,; Ruijgrok,

1979; Watanatada and Ben-Akiva, 1978). The various methods proposed

o f f e r d i f f e r e n t s t r a t e g i e s f o r computing t h e s m a t i o n / i n t e g r a t i o n

over micro r e l a t i o n s , and include, among o t h e r s : t h e ' n a i v e ' approach,

sample enumeration methods, and c l a s s i f i c a t i o n approaches.

The naive approach c o n s i s t s of t h e d i r e c t s u b s t i t u t i o n of

aggregate o r average values o f t h e explanatory v a r i a b l e s i n t o t y p i c a l l y

non-linear, micro r e l a t i o n s , and it has been found t h a t t h e aggregation

b i a s may be severe i n t h i s case. I n t h e sample enumeration approach,

t h e impact of a given p o l i c y on each i n d i v i d u a l , i n a r e p r e s e n t a t i v e

sample, i s determined from t h e disaggregate model and population

f o r e c a s t s a r e t h e n computed by straightforward sumnation of t h e e f f e c t

over i n d i v i d u a l s according t o t h e sampling s t r a t e g y . This method i s

considered t o be p a r t i c u l a r l y u s e f u l f o r estimating impacts f o r

short-term p o l i c i e s ( s e e Ben-Akiva and Atherton, 1977). but must be modified when t h e c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s of t h e population change over t h e

f o r e c a s t i n g period ( s i n c e it cannot be assumed t h a t t h e d i s t r i b u t i o n of observable a t t r i b u t e s remains c o n s t a n t ] .

I n t h e c l a s s i f i c a t i o n approach, t h e t o t a l population i s p a r t i t i o n e d

i n t o r e l a t i v e l y homogeneous groups and then average (group) values of

t h e explanatory v a r i a b l e s a r e i n s e r t e d i n t o t h e disaggregate model t o

( * )

determine demand i n each group according t o t h e naive approach

.

The accuracy and e f f i c i e n c y of t h e method depends on t h e c l a s s i f i c a t i o ninvolved, e.g. t h e t y p e and number of groups and t h e c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s

of t h e v a r i a b l e s included.

[*I

I n terms of i t s aggregation c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s , t h e p r a c t i c e i n B r i t i s h s t u d i e s w i t h use of market segment d i f f e r e n t i a t e d models, may perhaps b e s t be seen a s a v a r i a t i o n of t h i s c l a s s i f i c a t i o nFor

mode

choice s t u d i e s where only s h o r t term e l a s t i c i t i e s a r e required, t h e r e i s a consensus t h a t aggregating micro-relations, i . e .' t h e 'disaggregate' approach, i s both f e a s i b l e , e f f i c i e n t and hence

d e s i r a b l e . However, i n longer term contexts where l o c a t i o n

( d i s t r i b u t i o n ) models need t o be considered and/or when network flows

a r e required t h e problem becomes much more involved. Very few s t u d i e s

have attempted t h e aggregation of micro-models i n t h e s e contexts so

it i s premature t o make d e f i n i t i v e judgements. One which did, t h e

SIGMO study ( P r o j e c t Bureau I n t e g r a l T r a f f i c and Transportation S t u d i e s ,

1977) encountered severe problems i n attempting t o r e c o n c i l e micro

d e s t i n a t i o n choice models with aggregate t r i p p a t t e r n s and abandoned

t h e disaggregate approach i n favour of an e x i s t i n g d i s t r i b u t i o n model

based on g e n e r a l i s e d c o s t s . More g e n e r a l l y , Reid (1977) has noted t h a t

while i n p r i n c i p l e a disaggregate model has a b e t t e r chance of

capturing t h e e s s e n t i a l c a u s a l i t y i n t h e d a t a , i n p r a c t i c e

"...

if t h e behavioural theory i s weak o r t h e models u n t e s t e d a g a i n s t experience, such a s with current i n d i v i d u a l l o c a t i o n models, t h e y may f a i l t o include some important f a c t o r s which a r e embodied i n aggregate o r summary v a r i a b l e s which merely show a c o r r e l a t i o n t o demand. These a r e more l i k e l y t o pick up unknown e f f e c t s. . .

(and). . .

i f adequate disaggregate d a t aw i l l not be a v a i l a b l e f o r f o r e c a s t i n g , models c a l i b r a t e d on aggregate d a t a w i l l be more accurate."

In t h e e a r l y 1970's t h e process of aggregation was u s u a l l y viewed

a s t h e r a t h e r s t r a i g h t f o r w a r d s o l u t i o n of a numerical problem which was

well understood i n p r i n c i p l e . I n p r a c t i c e , however, it has shown i t s e l f t o be a highly n o n - t r i v i a l process which embraces not only

considerations of numerical e f f i c i e n c y , but a l s o questions r e l a t i n g t o

t h e a v a i l a b i l i t y of f o r e c a s t s f o r i n d i v i d u a l explanatory v a r i a b l e s and

t h e s t a b i l i t y of t h e d i s t r i b u t i o n of explanatory v a r i a b l e s over time.

Furthermore, t h e r e i s a l s o concern about t h e r e l a t i o n of p r e d i c t i o n s t o

estimation and d a t a designs; t h e r e f o r e , any comparison of 'aggregatet

and 'disaggregatet models must involve, i m p l i c i t l y o r e x p l i c i t l y , a

3 . DATA COLLECTION AND MEASUREMENT

3.1 Representation and measurement of t r a v e l a t t r i b u t e s

I n any p a r t i c u l a r study, out of t h e l a r g e v a r i e t y of p o t e n t i a l l y

a v a i l a b l e f o r e c a s t i n g methods ( e .g. cross-sectional a n a l y s i s ; panel

data methods; aggregate time s e r i e s approaches) and estimation

techniques, data considerations alone w i l l normally r e s t r i c t t h e choice

t o one s i n g l e method. H i s t o r i c a l l y , t h e c r o s s - s e c t i o n a l approach has

c l e a r l y dominated, t y p i c a l l y i n conjunction with revealed preference

methods, although a l t e r n a t i v e approaches based, f o r example, on s t a t e d

p r e f e r e n c e s / i n t e n t i o n s , have been p r e f e r r e d on s e v e r a l occasions ( s e e

Ortuzar, 1980a). However, t h e general problem of discounting f o r t h e

over-enthusiasm o f respondents ( t h e 'yeah' b i a s ) has not y e t been

solved, and it has r e c e n t l y been suggested t h a t s t a t e d and revealed

preference methods may perhaps be b e t t e r used i n a complementary fashion,

where i n s i g h t s can be obtained which would not a r i s e i f e i t h e r approach

were used alone Csee, f o r example, Hensher and Louviere, 1979; Gensch,

1980). We have argued elsewhere, ( ~ i l l i a m s and Ortuzar, 1980a), t h a t it

i s not p o s s i b l e a t t h e cross-section t o discriminate between a l a r g e

v a r i e t y of p o s s i b l e sources of dispersion i n d a t a p a t t e r n s (such a s

preference d i s p e r s i o n , c o n s t r a i n t s , h a b i t e f f e c t s , e t c . ) . Panel d a t a

o r more simply, before-and-after information, may o f f e r some means t o

d i r e c t l y t e s t and perhaps r e j e c t hypotheses r e l a t i n g t o response, ( s e e

an i n t e r e s t i n g example i n Johnson and Hensher, 1980). On t h e o t h e r hand

models b u i l t on ' l o n g i t u d i n a l ' ( a s opposed t o cross-sectional d a t a )

have t e c h n i c a l problems of t h e i r own (e.g. how b e s t t o 'pool' t h e

information), b u t a discussion of t h e i r m e r i t s i s beyond t h e scope of

t h i s paper.

A r e l a t e d a r e a of concern has t o do with t h e problem o f measurement.

We wish t o d i s c u s s b r i e f l y h e r e t h e implications f o r parameter estimates

of using d i f f e r e n t measurement techniques and/or philosophies. For a

deeper i n s i g h t i n t o t h e problem we r e f e r t h e reader t o t h e e x c e l l e n t

discussions by Daly (1978) and Bruzelius (1979). The problems involved

i n obtaining measures of explanatory v a r i a b l e s (e.g. c o s t and time

requirements by a l t e r n a t i v e modes) a r e shown schematically i n Figure 2.

I d e a l l y we would l i k e t o o b t a i n information on t h e s e v a r i a b l e s a s

perceived by t h e commuter when t a k i n g h i s d e c i s i o n , e s p e c i a l l y i f we

about a f u t u r e s i t u a t i o n ? ) , but perhaps i n obtaining 'values of t i m e ' .

The f i g u r e r e f l e c t s t h e state-of-the-art i n t h e understanding o f t h e

r e l a t i o n s h i p s between ' a c t u a l ' , 'perceived', 'reported' and 'measured'

values. The t r o u b l e i s t h a t none of t h e arrows and boxes i n t h e f i g u r e

have y e t been q u a n t i f i e d . Knowledge i n t h i s a r e a , i s , l i t e r a l l y , sketchy!

The a n a l y s t i s t h e r e f o r e made t o choose between reported and measured ( o r

'engineering' o r ' s y n t h e s i s e d ' ) d a t a , and while models estimated on each

type of d a t a may prove reasonable i n themselves

"...

it i s very d i f f i c u l t t o p o s t u l a t e r e l a t i o n s h i p s t h a tw i l l allow models c a l i b r a t e d on reported d a t a t o be applied t o synthesised data o r v i c e versa." ( ~ a l y , 1978)

Most probably t h e s a f e s t way out i s t o c o l l e c t information on both

reported and engineering values and t o make comparisons i n o r d e r t o gain

i n s i g h t from t h e two approaches. This i s , of course, more c o s t l y and

time consuming and, a s Hensher ( 1 9 7 9 ~ ) and o t h e r s have remarked, it i s seldom t h e case t h a t t h e a n d y s t f i n d s himself with t h e luxury ( o r

embarassment) of a l t e r n a t i v e data/methods a t hand.

We mentioned above t h a t one p o s s i b l e and a l t e r n a t i v e use f o r a model,

i n s t e a d of f o r e c a s t i n g , i s t o employ it f o r e s t i m a t i n g , f o r example, values of time ( ~ r u z e l i u s , 1979; Daly, 1978; Hensher, 1972; McFadden,

1978b; Prashker, 1979; Quarmby, 1967; Train, 1977; Gunn, Mackie and

Ortuzar, 1980; and some of t h e references c i t e d t h e r e i n ) . An o l d i s s u e

i n t h i s context i s t h e 'trader/non-trader' question, e.g. should t h o s e

i n d i v i d u a l s who appear t o be faced with a dominant(*) o p t i o n be excluded

from t h e sample? As Daly (1978) has c l e a r l y pointed o u t , t h e answer i s

d e f i n i t e l y no! The main d i f f i c u l t y has a c t u a l l y been due t o a

misunderstanding: t h a t only

observable,

and hence measured ( o r measurable)a t t r i b u t e s should m a t t e r when defining whether an option i s dominant,

leaving out t h e c r u c i a l unobservables and/or unmeasured c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s .

I n t h i s sense, t h e l a r g e r t h e number of measured a t t r i b u t e s incorporated

i n t h e model, t h e smaller w i l l be t h e number of apparent 'non-traders' and,

b e t t e r s t i l l , t h e l e s s t h e i n f l u e n c e of unmeasured f a c t o r s (simply because

more of t h o s e a r e i n c o r p o r a t e d . )

( * ) An option which,

to the modeller,

looks b e t t e r i n every r e s p e c tthan t h e o t h e r s and happens t o be t h e chosen one ( i f it i s not t h e chosen one t h e i n d i v i d u a l i s deemed i r r a t i o n a l ! ) . Notice

t h a t t h i s i s not t o be confused with t h e i s s u e of

captive t r a v e l l e r s

(e.g. a person who needs'the c a r during t h e day) who should beThis brings us n a t u r a l l y i n t o the question o r using

a t t i t u d i n a l varia'bles feg. comfort, convenience, r e l i a b i l i t y ) t o

improve our models. (For a more complete discussion see,

Foerster, 19'(9b, Johnson, 1975; Spear, 1976; Stopher

e t

~1.1974; and Wemuth, 1978). I n terms of t h e influence of a t t i t u d i n a lmeasures on t h e value of other parameters and on the general

performance of a model, there

i s

conflicting evidence i n t h e l i t e r a t u r e . McFadden (1976),

f o r example, concluded t h a t choicewas explained, t o a g r e a t extent, by t h e typical level-of-service

variables used i n conventional studies and t h a t a t t i t u a n a l

(t)

measures added very l i t t l e explanatory power t o the models

.

More recently, however, Prashker (19'(9) has found t h a t including

measures of r e l i a b i l i t y (eg. r e l i a b i l i t y of finding a parking

space; r e l i a b i l i t y of bus a r r i v a l s )

,

both s u b s t a n t i a l l y increasedt h e explanatory power of the models ( f o r example, it produced mode-

specific constants which were not statistically d i f f e r e n t from zero),

1

and change s i g n i f i c m t l y the values of some p a r m e t e r s ( i n p a r t i -

cular the value of in-vehscle time). Once more, the s a f e s t recom-

mendation seems t o be t o examine the p o s s i b i l i t y of measuring some

'unconventional' f a c t o r s (eg. r e l i a b i l i t y , c o w o r t , convenience,

etc.) and t o t e s t f o r t h e i r e f f e c t s on t h e other parameter estimates

and model explanatory power. Again, however, t h i s would n a t u r a l l y

imply higher data collection and analysis c o s t s .

("1t

i s

f a i r t o say, though, t h a t t h e models discussed by McFadden3.2 Alternative sampling s t r a t e g i e s

The development and implementation of t r a v e l demand models

have t r a d i t i o n a l l y been associated with l a r g e data c o l l e c t i o n

e f f o r t s , involving, p r i n c i p a l l y , very expensive home interview

surveys. Because conventional aggregate models used data a t t h e

zonal l e v e l f a i r l y l a r g e random samples wererequired f o r c a l i b r a -

t i o n purposes, and it i s ~ e l l - ~ a m t h a t on many occasions t h e

c o s t and time consumed i n t h e c o l l e c t i o n and a n a l y s i s of the data

prevented t h e a n a l y s t s from examining a s u f f i c i e n t range of

a l t e r n a t i v e p o l i c i e s .

One of t h e advantages t r a d i t i o n a l l y c i t e d f o r disaggregate

models i s t h e e f f i c i e n c y with which they can make use of a v a i l a b l e

data and t h e p o t e n t i a l f o r reducing t h e time and e f f o r t expended

on data collection. A s we saw above, t h i s claim (together with

-

o t h e r s ) has not been universally achieved, but

it i s

t r u e t o s a y t h a t i n c e r t a i n s i t u a t i o n s t h e f a c t that disaggregate choice modelsuse observations of individual decision makers, r a t h e r than

geographically defined groups, can s u b s t a n t i a l l y reduce data col-

l e c t i o n costs. The r e s t o f t h i s s e c t i o n s u m a r i s e s two e x c e l l e n t

papers by Lerman and Manski (3.~76; 1979) Which c o n s t i t u t e t h e

state-of-the-art i n t h i s area.

The majority of a p p l i c a t i o n s of disaggregate cholce models

have r e l i e d on randomly sampled data, eg. s l i g h t v a r i a t i o n s on t h e

t y p i c a l home interview survey. A few s t u d i e s have used strati-

f i e d sampling, where t h e population of i n t e r e s t i s b v i d e d i n t o

groups according t o some c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s such a s c a r ownership

(which must be known i n advance) and each subpopulation is sampled

very expensive indeed

i n

cases wheee an option of i n t e r e s t has avery low p r o b a b i l i t y of s e l e c t i o n ; because t o achieve a-reasonable

representation of' t h e option i n question

it

i s necessary t o c o l l e c t a very l a r g e sample. A choice-based sample t t h a t i s , one whereobservations a r e drawn based on t h e outcome of t h e decision-aaking

process under study1 designed s o t h a t t h e number o f users o f t h e

low option i s

redetermined

o f f e r s one way t o solve t h i s problem.Choice-based samples a r e not uncommon i n t r a n s p o r t studies.

Typical examples a r e on-board t r a i n and bus surveys, and roadside

interviews i n t h e case of mode ehoice modelling. They can fre-

quently be obtained f a i r l y inexpensively, but (because o f t h e way

t h e parameters of ( d i s a g ~ e ~ a t e ) models a r e generally c a l i b r a t e d )

have seldom been used f o r c a l i b r a t i n g models ( s e e C o s s l e t t , 1980).

A s we w i l l see below each sampling s t r a t e g y r e s u l t s i n a d i f f e r e n t

d i s t r i b u t i o n of observed choices and c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s i n t h e sample

t h a t i n c e r t a i n s i t u a t i o n s t h e f a c t t h a t disaggreeate choice models

m e observations of individual decision makers, r a t h e r than

geographically defined groups. can s u b s t a n t i a l l y reduce data col-

l e c t i o n costs. The r e s t of t h i s section summarises two e x c e l l e n t

papera by Lerman nnd Manski (1976; 1979) which c o n s t i t u t e t h e state-.of-the-art i n t h i s area.

The majority of applications of disaggregate choice models

have r e l i e d on randomly sampled data, eg. s l i g h t v a r i a t i o n s on t h e

t y p i c a l home interview survey. A few studies have used s t r a t i -

f j e d sampling, where t h e population of i n t e r e s t i s chvided i n t o

groups according t o some c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s such a s c a r ownership

(which must be known i n advance) and each subpopulation i s sampled

-

very expensive indeed i n cases where an option of i n t e r e s t has a

very lor? p r o b a b i l i t y Of s e l e c t i o n ; because t o achieve a reasonable

representation of t h e option i n question

i t

i.s necessary t o c o l l e c t a very l a r g e sanple. A choice-based sample (that i s , one whereobservations a r e drawn based on t h e outcome of t h e decision-making

process under study) designed s o t h a t t h e number of users of t h e

low option i s predetermined o f f e r s one way t o solve t h i s problem.

Choice-based samples a r e not uncommon i n t r a n s p o r t s t u d i e s .

Yypical examples a r e on-board t r a i n and bus surveys, and roadside

interviews in t h e case of mode choice modelling. They can f r e -

quently be obtained f a i r l y inexpensively, hut (because of t h e way

t h e p a r m e t e r s of (disagyregate) models a r e generaU y c a l i b r a t e d )

have ackdom been used f o r c a l i b r a t i n g models ( s e e Cossleti;, 1900).

A s we w i l l see below each sampling s t r a t e g y r e s u l t s i n a d i f f e r e n t

d i s t r i b u t i o n of observed choices and c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s i n t h e sample

and hence each has a s s o c i a t e d

a

d i f f e r e n t c a l i b r a t i o n f h c t i o n (such a s l i k e l i h o o d l . Although t h e f i r s t two sanpling methodspresent no problems t o e x i s t i n g software, t h e choice-based

u.pproach needs some modirications (Lermm, hhnski and Atherton,

1976; Lerman and t.fansk~, 1976) o r e x i s t i n g programs w i l l

(*J produce biased paxameters

.

Given t h e existence of a p r a c t i c a l estimation procedure f o r

choice-based samples, t h e question i s what sampling s t r a t e g y

should be preferred. Leman and Fanski (1976; 1979) have argued

t h a t unfortunately, t h e anawer i s extremely s i t u a t i o n - s p e c i f l c

and depends on

...

...

...

.

. .

. . . . . . . . .

-....

...

...

. .

.

...

-

the c o s t o f various sampling methods-

t h e choice being modelled-

t h e c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s of t h e population under study-

t h e s o c i a l c o s t o f estimation e r r o r s i n terms ofa p p l i c a t i o n s of misguided p o l i c i e s

(T)

Random samples o f t e n r e q u i r e a major expenditure of time and -

money t o c o l l e c t .

.

Normally they should be based on homes-

i f done anywhere e l s e they would be choice-based because t h e respon-dent has already made a t r i p choice

-

wjth a l l t h e p r o b l e m associated with home interview surveys. However t h e r e i s scopef o r longer and more in-depth interviewing.

A fbrther problem of' random sarnples

i s

t h a t they o f f e r no opportunity t o i n c r e a s e t h e amount of information given a f i x e dsumple s i z e . Variation

i n

the

d a t a ( * ) cannot be c o n t r o l l e d i n t h i s c a s e , being r a t h e r a random outcome of t h e sao?.plin& process.S t r a t i f i e d samples on t h e o t h e r hand should help i n t h i s sense,

because even if t h e c h ~ s a c t e r i s t i c s of t h e population vary l i t t l e ,

t h e s m p l e i t ~ t e l f can have a h i & variance, i e , c e r t a i n s t r a t a

can be sampled a t d i f f e r e n t r a t e s from others. However, s , t r a t i -

f i e d samples a r e often more expensive than random ones b e c ~ u s e ,

i n order t o s q l e a t random f r m a subpopulation, one m u s t f i r s t

be able t o i s o l a t e the subpopulation; i n p r a c t i c e t h i s nay be

d i f f i c u l t (and expensive) t o achieve

C**).

. . .

...

...

. . . . . . . . . ...

..*...

.

.

. . . .

.

. .

(*)SeeGensch

(1900)

f o r an i n t e r e s t i n g example about t h e p o s s i b l e magnitude mf such c o s t s .(*)The more v a r i a t i o n i n t h e h t a , t h e more re1labl.e a r e t n e para-

meter estimates.

-.

**

( iTor exnmple one may need t o begin an interview t o f i n d o u t t h e

In general choice-based samples a r e t h e l e a s t expensive but

they r e q u i r e p r i o r ktiowledge of t h e r a t i o of t h e share.of t h e

e n t i r e populetion chooslng each a l t e r n a t i v e t o t h e sample shere.

Fortunntely, t h e former i s an aggregate s t a t i s t i c which might he

obtained from s e v e r a l sources (Lerman and Manski, 19.16). Another

problem of t h i s sampling s t r a t e g y i s t h a t of b i a s (*), o r a l t e r -

native]-y, how t o ensure t h a t t h e sample, given t h e u s e r s o f an

option, i o readam.. Lerman and Manski (1979) mention a s an

example 'the problem, i n an on-.bus survey, of allowing f o r t h e f a c t

t h a t sane routes may have a higher percentage of e l d e r l y users

while others may a t t r a c t primarily workers. Another c a s e i s t h a t

associated with high r e j e c t i o n r a t e s of mail-back questionnaires

where it

i s

u n l i k e l y t h a t t h edistribution

of c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s of those who choose t o respond w i l l be t h e same a s t h a t o f t h epopulation a s a whole.

Bearing all t h e above i s s u e s i n mind, Lenaen and Manski

(1976) concluded i n t h e i r paper

"...

I n a l l p r o b a b i l i t y t h e question o f sample deslgnw i l l remain a judgemental problem."

and we s e e no reason why we should challenge t h i s view.

4.

Model Specif ?cat ionHaving a v a i l a b l e , o r having decided t o c o l l e c t dJtta i n a

c e r t a i n way and o f a given type

-

t y p i c a l l ya

random sample of cross-sectional information on revealed preferences, where valuesof a t t r i b u t e s a r e e i t h e r measured o r synthesised

-

t h e a n a l y s ts t i l l has some o p t i o n s open i n terms o f t h e model s t r u c t u r e , I .

...

...

...

... . . .

-.

...

. . .

. .

.

...

...

...

...

s p e c i f i c a t i o n and estimation method t o use. I n s e c t i o n

5

we w i l l present a f a i r l y comprehensive review of t h e most widely recommendedmethod of estimating d i s c r e t e choice models

-

Maximum Likelihood(ML) estimation

-

with p a r t i c u l a r emphasis on disaggregate data.(Elsewhere, ( H a r t l e y and Ortuzar, 19801, we have discussed t h e method

a s applied t o t h e c a l i b r a t i o n of aggregate h i e r a r c h i c a l l o g i t modal

s p l i t models and compared it w i t h a l t e r n a t i v e procedures. ) F i r s t l y though, we wish t o b r i e f l y comment h e r e on t h e r e l a t e d problem o f

model s e l e c t i o n i n g e n e r a l .

4 . 1

Model s e l e c t i o nI n general, t h e s t r u c t u r e of a model, t h e v a r i a b l e s e n t e r i n g

it and t h e i r form, t h e form of t h e utility functions thenselves,

and so on, are matters f o r t e s t i n g and experimentation ( s e e

t h e e x c e l l e n t book by Learnel-, 19781, and a r e q u i t e o f t e n a s t r o n g

function of context and data a v a i l a b i l i t y . Aggregate models

have often been c r i t i c a l l y vi.ewed a s p o l i c y insensi.tivc, e i t h e r

because a key v a r i a b l e has been completely l e f t out of t h e model;

o r from some component(s) of t h e model thought t o be s e n s i t i v e t o

i t

(eg. i n e l a s t i c t r i p g e n e r a t i o n ) ; or because severe d i s t o r t i o n s could be introduced from s p e c i f i c a t i o n o r aggregation b i a s e r r o r s .I n t h i s sense t h e Amerlcan WPS system was p a r t i c u l a r l y weak

(Ben-Akiva

et

aZ.

,

1977).I n B r i t i s h p r a c t i c e , however; t h e concept o f g e n e r a l i s e d

c o s t s , together with network modifications, have been used t o t e s t

l

a very wide range of p o l i c i e s (eg. from road investments t o parking

I

r e s t r a i n t and park-and-ride systems), although t h e s e have only been I

i n t e r p r e t e d on t e ~ s of t h e v a r i a b l e s ( * ) : in-vehicle-time, out-of-

.

. .

...

.

. .

.

.

. ...

...

...

... .

. .

. . .

.

. .

. .

.

(*) Although disaggregate models include many more explanatory v a r i a b l e s , including socio-economic,-level-of-service and even a t t i t u d i n a l v a r i a b l e s , we mentioned i n s e c t i o n

3

t h a t most o f t h e s t a t i s t i c a l explanatory power of t h e models (excepting t h e l a r g e amount explained by mode-specific constants, T a l v i t i e and Kirshner, 1978) r e s t s i n r e l a t i v e l y few of t h e s e a t t r i b u t e s , including t h e usual level-of-service v a r i a b l e sv e h i c l e time and out-of-pocket c o s t s ( s u i t a b l e s c a l e d by t h e generalised

c o s t c o e f f i c i e n t ) . Also a l a r g e v a r i e t y of model s t r u c t u r e s have been

employed ( s e e t h e d i s c u s s i o n by W i l l i a m s , 1979) including both simultaneous

and s e q u e n t i a l model forms, and t h e p o l i c y responsiveness of models has

been found t o be c r i t i c a l l y dependent on model s p e c i f i c a t i o n , t o t h e extent

t h a t c e r t a i n models s i n c e have been recognised a s ' p a t h o l o g i c a l 1

G . e . implied e l a s t i c i t i e s of t h e wrong s i g n ) because t h e i r s t r u c t u r e s

were not p r o p e r l y diagnosed f o r s p e c i f i c a t i o n e r r o r s ( s e e Senior and

Williams, 1977; and Williams and Senior, 1977).

The c o n s i d e r a t i o n of a v a i l a b l e a l t e r n a t i v e s (which could a l s o be

discussed a s an aggregation i s s u e ) i s another p a r t of t h e s p e c i f i c a t i o n process with s t r o n g i m p l i c a t i o n s f o r policy s e n s i t i v i t y . I n t h e v a s t

m a j o r i t y of aggregate s t u d i e s only b i n a r y choice between c a r and public

t r a n s p o r t has been considered, w i t h t h e consequence t h a t t h e multimodal

problem h a s not been t r e a t e d very s e r i o u s l y . I n t h e b e s t c a s e s t h e

consideration of a l t e r n a t i v e public t r a n s p o r t options has been r e l e g a t e d

t o t h e assignment s t a g e , employing 'all-or-nothing' o r 'multipathl a l l o c a t i o n

of t r i p s t o sub-modal network l i n k s . We have given elsewhere, ( H a r t l y and

Ortuzar, 1980), a p r a c t i c a l example of f i t t i n g a r a t h e r more general

s t r u c t u r e than t h e simple 1DtL t o aggregate modal s p l i t d a t a f o r t h r e e

modes ( c a r , bus and t r a i n ) and show how a p r i o r i notions which l e d u s

t o p o s t u l a t e such s t r u c t u r e were confirmed by a p p r o p r i a t e s t r u c t v a l

diagnosis t e s t s . Here we w i l l concentrate on disaggregate models both because t h e f u l l range of i s s u e s i n t h e i r s p e c i f i c a t i o n a r e more apparent

and because t h e y have been more thoroughly a i r e d and discussed.

We mentioned above t h a t t h e f i n a l s p e c i f i c a t i o n of a model t e n d s t o he a s t r o n g f u n c t i o n of context and d a t a a v a i l a b i l i t y . A p r i o r i

notions and t h e o r e t i c a l i n s i g h t a l s o provide valuable h e l p while another

important pragmatic f a c t o r i s t h e a v a i l a b i l i t y of s p e c i a l i s e d software.

In f a c t , one reason why linear-in-the-parameters l o g i t (and simple b i n a r y p r o b i t ) models have been so popular i s t h a t t h e y can e a s i l y be estimated

using a v a i l a b l e software [for w e l l documented examples, s e e Boyce, Desfor,

e t al., 1974; Domencich and McFadden, 1975; Ben-Akiva and Atherton, 1977;

Hensher, 1 9 7 9 ~ ; and T a l v i t i e and Kirshner, 1978) w h i l s t o t h e r more general

forms normally present enormous d i f f i c u l t i e s ( s e e t h e d i s c u s s i o n on

On t h e o t h e r hand, t h e l i m i t a t i o n s of 'simple scaleable choice models1 t y p i f i e d by t h e

MNL

s t r u c t u r e have been one o f t h e prime motivations behind t h e i n t e r e s t i n a l t e r n a t i v e models of t h e decision process; although we have argued elsewhere ( ~ i l l i a m s and Ortuzar,1980a) t h a t , in a c e r t a i n sense, t h e development of more general randomu t i l i t y s t r u c t u r e s (such a s t h e M N P ) has removed some of t h e o r i g i n a l j u s t i f i c a t i o n s f o r building such models. However, t h i s does not mean t h a t t h e more conventional models a r e n e c e s s a r i l y appropriate; indeed,

it i s often u s e f u l and d e s i r a b l e t o examine competing frameworks. One I

1

cause f o r concern, though, i s t h a t d i f f e r e n t model s t r u c t u r e s and forms tend t o produce d i f f e r e n t parameter estimates and response e l a s t i c i t i e s , whilst we do not have means t o discriminate between them a t t h e cross- s e c t i o n (see TTilliams and Ortuzar, 1980a).

4.2

Choice s e t determinationOne of t h e f i r s t problems an analyst has t o solve, given a t y p i c a l ( i . e . as defined above) data s e t i s t h a t of deciding which a l t e r n a t i v e s

a r e a v a i l a b l e t o each individual i n t h e sample. As Hensher ( 1 9 7 9 ~ ) has

1

noted". . .

Choice s e t determination.

.

.

i s t h e mast d i f f i c u l t ' o f all t h e i s s u e s t o resolve. It r e f l e c t s...

t h edilemma which a modeller has t o t a c k l e m a r r i v i n g at, a s u i t a b l e trade-off between modelling relevance and modelling complexity. Usually, however,

data

maiZab;iZitg

acts

as a

~ardstick."

(our emphasis)It

i s

extremely d i f f i c u l t t o decide on an i n d i v i d u a l ' s choice s e t unless one asks him; t h e r e f o r e t h e problem i s c l o s e l y oonnec-t e d with t h e already discussed dilemma of whether t o use reported

or measured data. Yhe obvious procedures o f ( a ) Caking i n t o

account only those a l t e r n a t i v e s which a r e e f f e c t i v e l y chosen i n

t h e sample; o r

(b)

t o assume t h a t everybody hasa l l

a l t e r n a t i v e s a v a i l a b l e (and hence Let t h e model decide t h a t t h e choice proba-b i l i t i e s of t h e u n r e a l i s t i c a l t e r n a t i v e s a r e low o r zero) have

a l s o obvious disadvsntages.- For example, i n t h e former case it

(due t o the s p e c i f i c sanple o r s a p l i n g tecnnique). I n t h e

l a t t e r case, t k h c l u s i o n of too many a l t e r n a t i v e s may a f f e c t the

discriminatory c a p a c i t i e s of t h e model, i n t h e sense t h a t a model

capable of dealing with u n r e a l i s t i c a l t e r n a t i v e s may not be a b l e

t o describe adequately t h e choices among r e a l i s t i c options ( s e e ,

Huijgrok, 1979). Fortunately, i n t h e context t h a t i n t e r e s t us

here

-

mode choice modelling-

t h e number of a l t e r n a t i v e s i s usually small and t h e problem should not be severe.By

c o n t r a s t , i n destination choice modelling ( l e . t r i pd i s t r i b u t i o n ) t h e i d e n t i f i c a t i o n of a l t e r n a t i v e s i n t h e choice s e t

i s a c r u c i a l matter, and not simply because t h e t o t a l number of

a l t e r n a t i v e s i s usually very high(*).

-

To i l l u s t r a t e t h i s , con-s i d e r t h e case of modelling t h e behaviour of a group of individuals

who vary a great deal i n terms of t h e i r knowledge of p o t e n t i a l

destinations (owing perhaps t o varying lengths of residence i n t h e

d e s c r ~ b e t h e r e l a t i o n s h i p between predicted

utilities

and observed choices, may be influenced a s much by v a r i a t i o n i n choice s e t samong individuals (which a r e

not

f u l l y accounted f o r i n t h e model),

a s by v a r i a t i o n s i n a c t u a l preferences (which a r e accounted I'Or).

Because changes i n t h e nature O f destinations may a f f e c t both

choice s e t a d preferences t o d i f f e r e n t degrees, t h i s confusion

may be l i k e l y t o plqf havoc with t h e use of t h e models i n fore-

c a s t i n g o r i n tne p o s s i b i l i t y of t r a a s f e r r i n g t h e i r s p e c i f i c a t i o n

over space. I t i s i n t e r e s t i n g t o note i n t h i s context t h a t

McFadden (1978a) has shown t h a t f o r a

MNL,

t h e model parameterscan be estimated without b i a s by sampling a l t e r n a t i v e s a t random

from t h e F u l l s e t of options, with appropriate adjustments i n the

e s t h a t i o n mechanisms. This

-.

i s

,however, not possible f o r t h eKMP, f o r example, p r e c i s e l y due t o i t s improved s p e c i f i c a t i o n which

allows f o r i n t e r a c t i o n between all a l t e r n a t i v e s .

4.3 Defining t h e form of t h e u t i l i t y function

Another a r e a of concern i n ' s p e c i f i c a t i o n searches' r e l a t e s t o t h e

form of t h e u t i . l i t y functions. Although t h e r e i s broad agreement among

e x p e r t s t h a t f o r mode choice modelling t h e

convenient

a s s w p t i o n of' r e p r e s e n t a t i v e

'

u t i l i t i e s w i t h linear-in-the-parameters (LTP) formsshould present l i t t l e d i f f i c u l t y , i n o t h e r contexts such as d e s t i n a t i o n

choice modelling'*' t h e general agreement i s t h a t LTP u t i l i t y f u n c t i o n s

a r e not v a l i d ( s e e , f o r example, F o e r s t e r , 1979a; Daly, 1979; Louviere

and Meyer, 1979). The problem t h i s time i s p a r t l y t h e l a c k of a p p r o p r i a t e estimation software, and p a r t l y theoretical(**! Three

general approaches have been proposed t o deal with t h i s problem:

-

t h e use of f u n c t i o n a l measurement/conjoint a n a l y s i s techniques w i t h experimental design d a t a ( ~ e r m a n andLouviere, 1978; Hensher, 1979a, 1979b; Hensher and

Louviere, 1979

1.

-

t h e use of 'form searches' by means o f s t a t i s t i c a ltransformations (e.g. t h e Box-Cox method) a s i n t h e

work o f Gaudry and Wills (1977).

-

t h e c o n s t r u c t i v e use of t h e economic theory i t s e l f f o r t h e d e r i v a t i o n of form (Train and McFadden, 1978;Hensher and Johnson, 1980).

Exploring t h i s i s s u e f u r t h e r would be o u t s i d e t h e scope o f t h i s paper

but we wish t o mention not o n l y t h a t non-linear u t i l i t y forms imply

d i f f e r e n t trade-off mechanisms than t h o s e u s u a l l y a s s o c i a t e d with a

concept l i k e t h e 'value-of-time'; but a l s o , and more importantly,

t h a t model e l a s t i c i t i e s and f o r e c a s t i n g power have been shown t o

vary d r a m a t i c a l l y w i t h f u n c t i o n a l form ( s e e , Dagenais, Gaudry and

Liem, 1980). Thus t h e i s s u e has important i m p l i c a t i o n s f o r model

design and hypothesis t e s t i n g .

.

.

.

... .

.

.

... . . . ...

...

...

. . . .

.

.

.

.

.

...

(*) A f u r t h e r major challenge i n d e s t i n a t i o n choice modelling (and i n a d d i t i o n i n mode choice modelling f o r non-work journeys such a s shopping t r i p s ) i s

how t o measure and/or r e p r e s e n t t h e a t t r a c t i v e n e s s of d e s t i n a t i o n s . For t h e case of mode choice f o r t h e journey-to-eork t h i s i s not a problem because i n t h e s h o r t term it c m b e s a f e l y assumed t h a t d e s t i n a t i o n s a r e f i x e d ; t h e r e f o r e , t h e i r a t t r a c t i o n s a r e common t o a l l competing modes and t h u s cancel o u t . When t h i s assumption does not hold ( a s i s t h e case with shopping trips) we f a c e a problem which h a s , so f a r a s we a r e aware, no s a t i s f a c t o r y answers.

( * * ) S p e c i f i c a l l y t h e problem i s t h a t f o r non-linear u t i l i t y expressions t h e r e

4.4

Model s t r u c t u r e and v a r i a b l e s e l e c t i o nRaving solved o r simply avoided ( a s i n our case) t h e

aforementioned problems we have t o deal with tm f u r t h e r

obstacles:

-

what model form land s t r u c t u r e ) t o use, eg. l o g i t-

given t h e s t r u c t u r e ,what

v a r i a b l e s shouLd e n t e r t h e u t i l i t y f'unctions and i n whatf o m

We t h i n k

it

i s f a i r t o say t h a t t h e question o f model s t r u c t u r e can only be resolved by examining t h e p a r t i c u l a r s i t u a t i o n under study.If we have reasons t o b e l i e v e t h a t a l t e r n a t i v e s a r e independent and

t h a t v a r i a t i o n s in t a s t e among i n d i v i d u a l s i n t h e population a r e not important (.e.g. we can speak of a s i n g l e value, r a t h e r t h a n a

d i s t r i b u t i o n , f o r t h e c o e f f i c i e n t s multiplying t h e a t t r i b u t e s e n t e r i n g

t h e u t i l i t y f u n c t i o n s ) , t h e n we may c o n f i d e n t l y choose t h e MNL model.

I f , on t h e o t h e r hand, t h e above conditions a r e not met o r if we a r e not c e r t a i n , t h e n we

shouZd t e s t a l t e r n a t i v e (more complex) model

s t r u c t u r e s a g a i n s t t h e convenient MNL. For example, i f we suspect t h a t

c o r r e l a t i o n between a l t e r n a t i v e s may be a s e r i o u s problem, we can

e i t h e r t e s t i f t h e 'independence from i r r e l e v a n t a l t e r n a t i e s ' condition

i s s a t i s f i e d [McFadden, Tye and T r a i n , 1976) o r , b e t t e r s t i l l , e s t i m a t e

a h i e r a r c h i c a l l o g i t model which includes b u i l t - i n s t r u c t u r a l diagnosis

t e s t s ( s o b e l , 1980; Ortuzar, 1980b; Ortuzar 1 9 8 0 ~ ) . On t h e o t h e r hand,

if we have reasons t o b e l i e v e t h a t t h e r e a r e s t r o n g t a s t e v a r i a t i o n s e f f e c t s , we might have t o t r y and f i t a 'random c o e f f i c i e n t s ' model.

The simplest one

i s

t h e CRA Hedonics model (Cardell and Reddy, 1977) which s t i l l has t h e r e s t r i c t i o n of assuming non-correlated a l t e r n a t i v e sa s t h e MNL. The most g e n e r a l model s t r u c t u r e p o s s i b l e , and sadly t h e

more complex t o e s t i m a t e c * ) , i s t h e MNP model which allows f o r t h e e x i s t e n c e of both c o r r e l a t i o n and t a s t e v a r i a t i o n s i n t h e d a t a .

It i s important t o r e a l i s e t h a t use of an inadequate model, such a s

t h e MNL, can l e a d t o s e r i o u s e r r o r s (~ausman and Wise, 1978; Horowitz,

1978, 1979a, l979b, 19801 and s t u d i e s on t h e comparison of a l t e r n a t i v e

... . . . . . . . . .

...

-

. . . ... . . .

... ... . . . . . .

model s t r u c t u r e s using simulated data, such a s those described i n Ortuzar (1978, 1979, 1980a) and ~ i l l i a m s and Ortuzar (1980a) among o t h e r s , have tended t o confirm t h i s view.

Even i f the analyst i s convinced ( o r has no choice but t o

be convinced) t h a t a given model s t r u c t u r e (say a MNL model) i s adeg,uate and t h a t linear-in-the-parmeters u t i l i t y Functions pose

no d i f f i c u l t i e s , he has

s t i l l

t o decide what variables should e n t e r t h e u t i l i t y expressions, and i n what form. This questioni s p a r t i c u l a r l y relevant i n t h e case of socio-economic variables.

I n disaggregate modelling work t h e most common approach u n t i l t h e

mid-1970's was t o add these variables a s additional l i n e a r terms;

t h i s

i s

consistent with t h e hypothesis t h a t any trade-off mecha- nisms involving say, time and c o s t s , a r e the same f o r a l lindividuals.

Two

a l t e r n a t i v e approaches allow d i f f e r e n t trade-off functions for groups of people with d i f f e r e n t characteristics. The f i r s t ,which

i s

f'uJ.1~ consistent with t h e requirement of observing groups of individuals with t h e sane choices and c o n s t r a i n t s ,i s

t o s t r a t i * the sample on t h e basis of t h e individual charac-

t e r i s t i c s and t o c a l i b r a t e

a

model f o r each market segment. I n t h i s w a y t h e model. coefficients a r e allowed to vary f o r t h ed i f f e r e n t market segments, thus r e s u l t i n g i n p o t e n t i a l l y d i f f e r e n t

trade-off mechanisms(*). The problem i s , a s usual, one of data:

t h e l a r g e r the number of market segnents, the smaller t h e number

of observations on each f o r a given s m p l e size. The second one,

which can be used i n conjlulction with t h e first, i s t o express

c e r t a i n coefficients (eg. of t h e time o r cost v a r i a b l e s ) a s a

function of an individual descriptor, usually income (see the

discussion by Train and McFadden, 19'18). I n a value-of-time

context t h i s would, f o r example, r e s u l t i n time being valued a s

a percentage of t h e wage r a t e I~cFadden, 197b).

The decision about what variables enter t h e u t i l i t y function

and i n what form (eg. level-of-service v a r i a b l e s being generic o r

mode-specific, etc.1

i s

usual% approached i n a stepwise fashion by t e s t i n gif

t h e e x t r a v a r i a b l e o r form adds e x t r a explanatory power t o the model. This i s r e l a t e d t o questions of modelc r e d i b i l i t y and policy s e n s i t i v i t y i n the following sense; it may

often occur t h a t

a

v a r i a b l e whichi s

considered t o be important, e i t h e r on strong a p r i o r i grounds o r becauseit

i s a key one i n t h e policy-model i n t e r f a c e leg. a c o s t v a r i a b l e i n a study of p r i c i n gmechanisms), would be l e f t o u t a s s t a t i s t i c a l l y insigtlificant by a

s t e m s e selection procedure. I n such a case, t h e tendency has

been t o override t h e 'automatic' s e l e c t i o n procedure ( s e e Gunn

and Bates, 1980). The stepwise s e l e c t i o n of v a r i a b l e s is usually done a s p a r t of t k e model estimation phase; s o we

will

postpone a discussion on methods t o do t h i s u n t i l section

5.2.

5.

MODEL ESTIMATION5.1

General statement o f t h e problem ("I n t r a v e l demand modelling ( a s i n most modelling exercises)

.

i n t e r e s t centres on finding a cau8aZ r e l a t i o n s h i p between onevariable, o r s e t of v a r i a b l e s , held t o be dependent on another

variable, o r s e t of variables. The purpose of t h e exeraise i s

t o p r e d i c t what value t h e dependent variable

w i l l

take given p a r t i c u l a r known o r bypothesised ( f o r e c a s t ) values of t h e...

.

. . .

. . .

. . .

.

.

...

...

...

. . .

...

...

. .

.

(*) I w i l l draw heavily here on unpublished seminar n o t e s by Hugh Gunn, with whom I have a l s o benefited g r e a t l y from discussions i n a l l