City, University of London Institutional Repository

Citation:

Friston, K. J., FitzGerald, T., Rigoli, F., Schwartenbeck, P., O'Doherty, J. &

Pezzulo, G. (2016). Active inference and learning. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews,

68, pp. 862-879. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.022

This is the published version of the paper.

This version of the publication may differ from the final published

version.

Permanent repository link:

http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/16681/

Link to published version:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.022

Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research

outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience.

Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright

holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and

linked to.

City Research Online:

http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/

publications@city.ac.uk

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Neuroscience

and

Biobehavioral

Reviews

j o u r n a l ho me p ag e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / n e u b i o r e v

Active

inference

and

learning

Karl

Friston

a,∗,

Thomas

FitzGerald

a,b,

Francesco

Rigoli

a,

Philipp

Schwartenbeck

a,b,c,d,

John

O’Doherty

e,

Giovanni

Pezzulo

faTheWellcomeTrustCentreforNeuroimaging,UCL,12QueenSquare,London,UnitedKingdom bMax-Planck—UCLCentreforComputationalPsychiatryandAgeingResearch,London,UnitedKingdom cCentreforNeurocognitiveResearch,UniversityofSalzburg,Salzburg,Austria

dNeuroscienceInstitute,Christian-Doppler-Klinik,ParacelsusMedicalUniversitySalzburg,Salzburg,Austria eCaltechBrainImagingCenter,CaliforniaInstituteofTechnology,Pasadena,USA

fInstituteofCognitiveSciencesandTechnologies,NationalResearchCouncil,Rome,Italy

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received5March2016

Receivedinrevisedform15June2016 Accepted17June2016

Availableonline29June2016

Keywords:

Activeinference Habitlearning Bayesianinference Goal-directed Freeenergy Informationgain Bayesiansurprise Epistemicvalue Exploration Exploitation

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Thispaperoffersanactiveinferenceaccountofchoicebehaviourandlearning.Itfocusesonthe distinc-tionbetweengoal-directedandhabitualbehaviourandhowtheycontextualiseeachother.Weshow thathabitsemergenaturally(andautodidactically)fromsequentialpolicyoptimisationwhenagents areequippedwithstate-actionpolicies.Inactiveinference,behaviourhasexplorative(epistemic)and exploitative(pragmatic)aspectsthataresensitivetoambiguityandriskrespectively,whereepistemic (ambiguity-resolving)behaviourenablespragmatic(reward-seeking)behaviourandthesubsequent emergenceofhabits.Althoughgoal-directedandhabitualpoliciesareusuallyassociatedwithmodel-based

andmodel-freeschemes,wefindthemoreimportantdistinctionisbetweenbelief-freeandbelief-based

schemes.Theunderlying(variational)beliefupdatingprovidesacomprehensive(ifmetaphorical) pro-cesstheoryforseveralphenomena,includingthetransferofdopamineresponses,reversallearning,habit formationanddevaluation.Finally,weshowthatactiveinferencereducestoaclassical(Bellman)scheme, intheabsenceofambiguity.

©2016TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierLtd.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Contents

1. Introduction...863

2. Activeinferenceandlearning...864

2.1. Thegenerativemodel...865

2.2. Behaviouractionandreflexes...867

2.3. Freeenergyandexpectedfreeenergy...867

2.4. Beliefupdating...868

2.5. Summary...869

3. RelationshiptoBellmanformulations...869

4. Simulationsofforaging...871

4.1. Thesetup...872

5. Simulationsoflearning...874

5.1. Contextandreversallearning...874

5.2. Habitformationanddevaluation...874

5.3. Epistemichabitacquisitionunderambiguity...874

5.4. Summary...875

∗Correspondingauthorat:TheWellcomeTrustCentreforNeuroimaging,InstituteofNeurology,12QueenSquare,LondonWC1N3BG,UnitedKingdom.

E-mailaddresses:k.friston@ucl.ac.uk(K.Friston),thomas.fitzgerald@ucl.ac.uk(T.FitzGerald),f.rigoli@ucl.ac.uk(F.Rigoli),philipp.schwartenbeck.12@ucl.ac.uk (P.Schwartenbeck),jdoherty@hss.caltech.edu(J.O’Doherty),giovanni.pezzulo@istc.cnr.it(G.Pezzulo).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.022

6. Conclusion...875

Disclosurestatement...877

Acknowledgements...877

AppendixA...877

References...878

1. Introduction

Therearemanyperspectivesonthedistinctionbetween goal-directedandhabitualbehaviour(BalleineandDickinson,1998;Yin andKnowlton,2006;Keramatietal.,2011;DezfouliandBalleine, 2013;DolanandDayan,2013;Pezzuloetal.,2013).Onepopular viewrestsuponmodel-basedandmodel-freelearning(Dawetal., 2005,2011).Inmodel-freeapproaches,thevalueofastate(e.g., beinginaparticularlocation)islearnedthroughtrialanderror, whileactionsarechosentomaximisethevalueofthenextstate(e.g. beingatarewardedlocation).Incontrast,model-basedschemes computeavalue-functionofstatesunderamodelofbehavioural contingencies(Gläscheretal.,2010).Inthispaper,weconsidera relateddistinction;namely,thedistinctionbetweenpoliciesthat restuponbeliefsaboutstatesandthosethatdonot.Inotherwords, weconsiderthedistinctionbetweenchoicesthatdependupona (freeenergy)functionalof beliefsaboutstates, asopposed toa (value)functionofstates.

Selectingactions basedupon thevalue ofstates only works whenthestatesareknown.Inotherwords,avaluefunctionisonly usefulifthereisnoambiguityaboutthestatestowhichthevalue functionisapplied.Here,weconsiderthemoregeneralproblem ofbehavingunderambiguity(Pearsonetal.,2014).Ambiguityis characterizedbyanuncertainmappingbetweenhiddenstatesand outcomes(e.g.,statesthatarepartiallyobserved)–andgenerally callsforpolicyselectionordecisionsunderuncertainty;e.g.(Alagoz etal.,2010;Ravindran,2013).Inthissetting,optimalbehaviour dependsuponbeliefsaboutstates,asopposedtostatesperse.This meansthatchoicesnecessarilyrestoninference,whereoptimal choicesmustfirstresolveambiguity.Wewillseethatthis reso-lution,throughepistemicbehaviour,isanemergentpropertyof (active)inferenceunderpriorpreferencesorgoals.These prefer-encesaresimplyoutcomesthat anagentorphenotypeexpects toencounter(Fristonetal.,2015).So,canhabitsbelearnedinan ambiguousworld?Inthis paper,weshowthatepistemichabits emergenaturallyfromobservingtheconsequencesof(one’sown) goal-directedbehaviour.Thisfollowsfromthefactthatambiguity canberesolved,unambiguously,byepistemicactions.

Toillustratethedistinctionbetweenbelief-basedandbelief-free policies,considerthefollowingexamples:apredator(e.g.,anowl) hastolocateaprey(e.g.,afieldmouse).Inthisinstance,thebest goal-directedbehaviourwouldbetomovetoavantagepoint(e.g., overhead)toresolveambiguityabouttheprey’slocation.The corre-spondingbelief-freepolicywouldbetoflystraighttotheprey,from anyposition,andconsumeit.Clearly,thisbelief-freeapproachwill onlyworkifthepreyrevealsitslocationunambiguously(andthe owlknowsexactlywhereitis).Asimilarexamplecouldbea preda-torwaitingforthereturnofitspreytoawaterhole.Inthisinstance, thechoiceofwhethertowaitdependsonthetimeelapsedsincethe preylastwatered.Thecommonaspectoftheseexamplesisthatthe beliefstateoftheagentdeterminestheoptimalbehaviour.Inthe firstexample,thisinvolvessolicitingcuesfromtheenvironment thatresolveambiguityaboutthecontext(e.g.,locationofaprey). Inthesecond,optimalbehaviourdependsuponbeliefsaboutthe past(i.e.,memory).Inbothinstances,avalue-functionofthestates oftheworldcannotspecifybehaviour,becausebehaviourdepends onbeliefsorknowledge(i.e.,beliefstatesasopposedtostatesofthe world).

Usually,inMarkovdecisionprocesses(MDP),belief-based prob-lemscallforanaugmentedstate-spacethatcoversthebeliefor informationstatesofanagent(Averbeck,2015)–knownasabelief MDP(Oliehoeketal.,2005).Althoughthisisanelegantsolution tooptimisingpoliciesunderuncertaintyabout(partiallyobserved) states,thecompositionofbeliefstatescanbecome computation-allyintractable;not leastbecausebeliefMDPsare definedover acontinuousbeliefstate-space(Cooper,1988;Duff,2002;Bonet andGeffner,2014).Activeinferenceoffersasimplerapproachby absorbinganyvalue-function intoa singlefunctional ofbeliefs. Thisfunctionalisvariationalfreeenergythatscoresthesurprise or uncertaintyassociated witha belief,in light ofobserved (or expected) outcomes. This means that acting to minimise free energyresolvesambiguityandrealisesunsurprisingorpreferred outcomes.We willseethatthissingleobjectivefunctioncanbe unpackedinanumberofwaysthatfitcomfortablywithestablished formulationsofoptimalchoicebehaviourandforaging.

In summary,schemesthat optimisestate-action mappings– viaavalue-functionofstates–couldbeconsideredashabitual, whereasgoal-directedbehaviourisquintessentiallybelief-based. Thisbegs thequestionas towhetherhabits canemergeunder belief-based schemes likeactive inference.In otherwords,can habits belearned by simplyobserving one’sown goal-directed behaviour?Weshowthisisthecase;moreover,habitformation isaninevitableconsequenceofequippingagentswiththe hypoth-esisthathabitsaresufficienttoattaingoals.Weillustratethese points,usingformal(informationtheoretic)argumentsand simu-lations.Thesesimulationsarebaseduponageneric(variational) beliefupdateschemethatshowsseveralbehavioursreminiscent ofrealneuronalandbehaviouralresponses.Wehighlightsomeof thesebehavioursinanefforttoestablishtheconstructvalidityof activeinference.

Thispapercomprisesfoursections.Thefirstprovidesa descrip-tionofactiveinference,whichcombinesourearlierformulations ofplanningasinference(Fristonetal.,2014)withBayesianmodel averaging(FitzGeraldetal.,2014)andlearning(FitzGeraldetal., 2015a,2015b).Importantly,action(i.e.policyselection),perception (i.e.,stateestimation)andlearning(i.e.,reinforcementlearning)all minimisethesamequantity;namely,variationalfreeenergy.Inthis formulation,habitsarelearnedundertheassumption(or hypoth-esis)thereisanoptimalmappingfromonestatetothenext,thatis notcontextortime-sensitive.1Ourkeyinterestwastoseeif

habit-learningemergesasaBayes-optimalhabitisationofgoal-directed behaviour,whencircumstancespermit.Thisfollowsageneralline ofthinking,wherehabitsareeffectivelylearnedastheinvariant aspectsofgoal-directedbehaviour(Dezfouliand Balleine,2013; Pezzuloetal.,2013,2014,2015).Italsospeakstothearbitration

betweengoal-directedandhabitualpolicies(Leeetal.,2014).The secondsectionconsidersvariationalbeliefupdatingfromthe per-spectiveofstandardapproachestopolicyoptimisationbasedonthe Bellmanoptimalityprinciple.Inbrief,wewilllookatdynamic pro-grammingschemesforMarkoviandecisionprocessesthatarecast intermsofvalue-functions–andhowtheensuingvalue(orpolicy) iterationschemescanbeunderstoodintermsofactiveinference.

Thethirdsectionusessimulationsofforaginginaradialmazeto illustratesomekeyaspectsofinferenceandlearning;suchasthe transferofdopamineresponsestoconditionedstimuli,asagents becomefamiliarwiththeirenvironmentalcontingencies(Fiorillo etal.,2003).Thefinalsectionconsiderscontextandhabitlearning, concludingwithsimulationsofreversallearning,habitformation anddevaluation(BalleineandOstlund,2007).Theaimofthese sim-ulationsistoillustratehowtheabovephenomenaemergefroma singleimperative(tominimisefreeenergy)andhowtheyfollow naturallyfromeachother.

2. Activeinferenceandlearning

Thissectionprovidesabriefoverviewofactiveinference.The formalismusedinthispaperbuildsuponourprevioustreatments ofMarkovdecisionprocesses(Schwartenbecketal.,2013;Friston etal.,2014,2015;Pezzuloetal.,2015,2016).Specifically,weextend sequentialpolicyoptimisationtoincludeaction-statepoliciesof thesortoptimisedbydynamicprogrammingandbackwards induc-tion(Bellman,1952;Howard,1960).Activeinferenceisbasedupon thepremisethateverythingminimisesvariationalfreeenergy.This leadstosomesurprisinglysimpleupdaterulesforaction, percep-tion,policyselection,learningandtheencodingofuncertainty(i.e., precision)thatgeneraliseestablishednormativeapproaches.

In principle, the following scheme can be applied to any paradigm or choice behaviour. Earlier applications have been used to model waiting games (Friston et al., 2013) the urn

taskandevidenceaccumulation(FitzGeraldetal.,2015a,2015b), trust games from behavioural economics (Moutoussis et al., 2014;Schwartenbecket al.,2015a, 2015b),addictivebehaviour (Schwartenbecketal.,2015c),two-stepmazetasks(Fristonetal., 2015)andengineeringbenchmarkssuchasthemountaincar prob-lem(Fristonetal.,2012a).Empirically,itishasbeenusedinthe settingofcomputationalfMRI(Schwartenbecketal.,2015a).More generally,in theoreticalbiology, active inferenceisa necessary aspectofanybiologicalself-organisation(Friston,2013),wherefree energyreflectssurvivalprobabilityinanevolutionarysetting(Sella andHirsh,2005).

Inbrief,activeinferenceseparatestheproblemsofoptimising actionandperceptionbyassumingthatactionfulfilspredictions baseduponperceptualinferenceorstate-estimation.Optimal pre-dictions are based on (sensory) evidence that is evaluated in relationtoagenerativemodelof(observed)outcomes.Thisallows onetoframebehaviourasfulfillingoptimisticpredictions,where theinherentoptimismisprescribedbypriorpreferences(Friston etal.,2014).Crucially,thegenerativemodelcontainsbeliefsabout futurestatesandpolicies,wherethemostlikelypoliciesleadto preferredoutcomes.Thisenablesactiontorealisepreferred out-comes,basedontheassumptionthatbothactionandperception aretryingtomaximisetheevidenceormarginallikelihoodofthe generativemodel,asscoredbyvariationalfreeenergy.

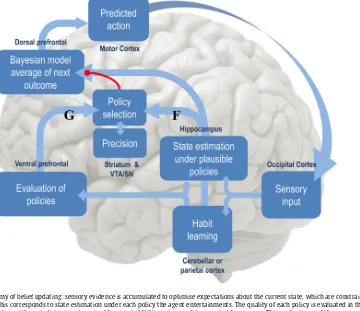

Fig.1,providesanoverviewofactiveinferenceintermsofthe functionalanatomyandprocessesimplicitintheminimisationof variationalfreeenergy.Inbrief,sensoryevidenceisaccumulatedto

[image:4.612.113.473.365.676.2]formbeliefsaboutthecurrentstateoftheworld.Thesebeliefsare constrainedbyexpectationsofpast(andfuture)states.This evi-denceaccumulationcorrespondstostateestimationundereach policytheagententertainments.Thequalityofeachpolicyisthen evaluatedintermsofitsexpectedfreeenergy.Theimplicitpolicy selectionthereforedepends onexpectationsaboutfuture states undereachpolicy,wheretheencodingoffuturestateslendsthe schemeanabilitytoplanandexplore.Afterthefreeenergiesof eachpolicyhavebeenevaluated,theyareusedtopredictthenext stateoftheworld,throughBayesianmodelaveraging(over poli-cies);inotherwords,policiesthatleadtopreferredoutcomeshave agreaterinfluenceonpredictions.Thisenablesactiontorealise pre-dictedstates.Onceanactionhasbeenselected,itgeneratesanew observationandtheperception-actioncyclebeginsagain.Inwhat follows,wewillseehowtheseprocessesemergenaturallyfrom thesingleimperativetominimise(expected)freeenergy,undera fairlygenericmodeloftheworld.

Asnotedabove,thegenerativemodelincludeshiddenstates inthepastandthefuture.Thisenablesagentstoselectpolicies that will maximise model evidence in the future by minimis-ingexpectedfreeenergy.Furthermore,itenableslearningabout contingenciesbaseduponstatetransitionsthatareinferred retro-spectively.WewillseethatthisleadstoaBayes-optimalarbitration between epistemic (explorative) and pragmatic (exploitative) behaviourthatisformallyrelatedtoseveralestablishedconstructs; e.g.,theInfomaxprinciple(Linsker,1990),Bayesiansurprise(Itti andBaldi,2009), thevalueofinformation (Howard,1966), arti-ficialcuriosity(Schmidhuber,1991),expectedutilitytheory(Zak, 2004)andsoon.Westartbydescribingthegenerativemodelupon whichpredictionsandactionsarebased.Wethendescribehow actionisspecifiedby(Bayesianmodelaveragesof)beliefsabout statesoftheworld,underdifferentmodelsorpolicies.This sec-tionconcludesbyconsideringtheoptimisationofthesebeliefs(i.e., inferenceandlearning)throughBayesianbeliefupdating.Thethird sectionillustratestheformalismofthecurrentsection,usingan intuitiveexample.

Notation. The parameters of categorical distributions over discretestatess ∈{0,1}aredenotedbycolumnvectorsof expecta-tionss ∈{0,1},whilethe∼notationdenotessequencesofvariables overtime;e.g., ˜s=(s1,...,sT).Theentropyofaprobability

distri-butionP(s)=Pr(S=s)isdenotedbyH(S)=H[P(s)]=EP[−lnP(s)], while the relative entropy or Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence isdenotedbyD[Q(s)||P(s)]=EQ[lnQ(s)−lnP(s)].Innerandouter productsareindicatedbyA·B=ATB,andA⊗B=ABTrespectively. We usea hatnotation todenote(natural)logarithms. Finally,P(o|s)=Cat(A)impliesPr(o=i|s=j)=Cat(Aij).

Definition. Activeinferencerestsonthetuple(O,P,Q,R,S,T,U):

•AfinitesetofoutcomesO

•AfinitesetofcontrolstatesoractionsU •AfinitesetofhiddenstatesS

•AfinitesetoftimesensitivepoliciesT

•Agenerative processR(˜o,˜s,u˜)thatgeneratesprobabilistic out-comeso∈Ofrom(hidden)statess∈Sandactionu ∈U •A generative model P(˜o,s,˜ ,) with parameters , over

out-comes,statesandpolicies∈T,where∈{0,...,K}returns asequenceofactionsut=(t)

•AnapproximateposteriorQ(˜s,,)=Q(s0|)...Q(sT|)Q()Q()

overstates,policiesandparameterswithexpectations (s

0,...,sT,,)

Remarks. The generative process describes transitions among (hidden) states in the world that generate observedoutcomes. Thesetransitions dependuponactions,whichdependonbeliefs aboutthenextstate.Inturn,thesebeliefsareformedusinga

gen-erativemodelofhowobservationsaregenerated.Thegenerative modeldescribeswhattheagentbelievesabouttheworld,where beliefsabouthiddenstatesandpoliciesareencodedby expecta-tions.Note thedistinctionbetweenactions(thatarepartofthe generativeprocessintheworld)andpolicies(thatarepartofthe generativemodelofanagent).Thisdistinctionallowsactionstobe specifiedbybeliefsaboutpolicies,effectivelyconvertinganoptimal controlproblemintoanoptimalinferenceproblem(Attias,2003; BotvinickandToussaint,2012).

2.1. Thegenerativemodel

ThegenerativemodelforpartiallyobservableMarkovdecision processescanbeparameterisedinageneralwayasfollows,where themodelparametersare={a,b,c,d,e,ˇ}:

(1.a)

(1.b)

(1.c)

(1.d)

(1.e)

Theroleofeachmodelparameterwillbeunpackedwhenwe consider model inversion and worked examples.For reference,

Table 1 provides a brief descriptionof this model’s states and parameters.Thecorresponding(approximate)posteriorover hid-denstatesandparametersx=(˜s,,)canbeexpressedintermsof theirexpectationsx=(s

0,...,sT,,)and=(a,b,c,d,e,)

(2)

Inthisgenerativemodel,observationsdependonlyupon the currentstate(Eq.(1.a)),whilestatetransitionsdependona pol-icy orsequenceof actions(Eq.(1.b)).This(sequential)policyis sampledfromaGibbsdistributionorsoftmaxfunctionofexpected freeenergy ,withinversetemperatureorprecision (Eq.

Table1

[image:6.612.37.567.78.705.2]donotdependonthepolicyand thenextstateisalways spec-ified (probabilistically) by thecurrent state(Eq. (1.c)).In other words,thereisonespecialpolicythat,ifselected,willgeneratethe samestatetransitionsandsubsequentactions,irrespectiveoftime orcontext.Thisisthehabitualorstate-actionpolicy.Conversely, when>0,transitionsdependonasequentialpolicythatentails orderedsequencesofactions(Eq.(1.b)).

Notethatthepolicyisarandomvariablethathastobeinferred. Inotherwords,theagententertainscompetinghypothesesor mod-elsofitsbehaviour,intermsofpolicies.Thiscontrastswithstandard formulations,inwhichone(habitual)policyreturnsanactionasa functionofeachstateu=(s),asopposedtotime,u=(t).Inother words,differentpoliciescanprescribedifferentactionsfromthe samestate,whichisnotpossibleunderastate-actionpolicy.Note alsothattheapproximateposteriorisparameterisedintermsof expectedstatesundereachpolicy.Inotherwords,weassumethat theagentkeepsaseparaterecordofexpectedstates–inthepast andfuture–foreachallowablepolicy.Essentially,thisassumesthe agentshaveashorttermmemoryforpredictionandpostdiction. Wheninterpretedinthelightofhippocampaldynamics,this pro-videsasimpleexplanationforphenomenalikeplace-cellresponses andphaseprecession(FristonandBuzsaki,2016).Aseparate repre-sentationoftrajectoriesforeachpolicycanbethoughtofintermsof asaliencymap,whereeachlocationcorrespondstoaputative pol-icy:e.g.,afixationpointforthenextsaccade(Fristonetal.,2012b; Mirzaetal.,2016).

Thepredictionsthatguide actionare basedupon aBayesian modelaverageofpolicy-specificstates.Inotherwords,policiesthe agentconsidersitismorelikelytobepursuingdominate predic-tionsaboutthenextoutcomeandtheensuingaction.Finally,allthe conditionalprobabilities–includingtheinitialstate–are parame-terisedintermsofDirichletdistributions(FitzGeraldetal.,2015b). The sufficientstatistics ofthese distributions areconcentration parametersthatcanberegardedasthenumberof[co]occurrences encounteredinthepast.Inotherwords,theyencodethenumber oftimesvariouscombinationsofstatesandoutcomeshavebeen observed,whichspecifytheirprobability–andtheconfidencein thatprobability.Inwhatfollows,wefirstdescribehowactionsare selected,givenbeliefsaboutthehiddenstateoftheworldandthe policiescurrentlybeingpursued.Wewillthenturntothemore difficultproblemof optimisingthebeliefsupon whichaction is based.

2.2. Behaviouractionandreflexes

Weassociateactionwithreflexesthatminimisetheexpected KLdivergencebetweentheoutcomespredictedatthenexttime stepandtheoutcomepredictedaftereachaction.Mathematically, thiscanbeexpressedintermsofminimising(outcome)prediction errorsasfollows:

(3)

Thisformulationofactionisconsideredreflexivebyanalogyto motorreflexesthatminimisethediscrepancybetween propriocep-tivesignals(primaryafferents)anddescendingmotorcommands orpredictions.Heuristically,actionrealisesexpectedoutcomesby minimisingtheexpectedoutcomepredictionerror.Expectations

aboutthenextoutcomethereforeenslavebehaviour.Ifweregard competingpoliciesasmodelsofbehaviour,thepredictedoutcome isformallyequivalenttoaBayesianmodelaverageofoutcomes, underposteriorbeliefsaboutpolicies(lastequalityabove).

2.3. Freeenergyandexpectedfreeenergy

Inactiveinference,alltheheavyliftingisdonebyminimising freeenergywithrespecttoexpectationsabouthiddenstates, poli-ciesandparameters.Variationalfreeenergycanbeexpressedasa functionoftheapproximateposteriorinanumberofways:

(4)

where ˜o=(o1,...,ot)denotes observationsupuntilthecurrent

time.

BecauseKL divergencescannotbeless thanzero,the penul-timateequalitymeansthat free energyis minimised when the approximateposteriorbecomesthetrueposterior.Atthispoint, thefreeenergybecomes thenegativelogevidenceforthe gen-erativemodel(Beal,2003).Thismeansminimisingfreeenergyis equivalenttomaximisingmodelevidence,whichisequivalentto minimisingthecomplexityofaccurateexplanationsforobserved outcomes(lastequality).

Withthisequivalenceinmind,wenowturntothepriorbeliefs aboutpoliciesthatshapeposteriorbeliefs−andtheBayesianmodel averaging that determines action. Minimising free energy with respecttoexpectationsensuresthattheyencodeposteriorbeliefs, givenobservedoutcomes.However,beliefsaboutpoliciesreston outcomesinthefuture,becausethesebeliefsdetermineactionand actiondeterminessubsequentoutcomes.Thismeansthatpolicies should,apriori,minimisethefreeenergyofbeliefsaboutthefuture. Eq.(1.e)expressesthisformallybymakingthelogprobabilityofa policyproportionaltothefreeenergyexpectedunderthatpolicy. TheexpectedfreeenergyofapolicyfollowsfromEq.(4)(Friston etal.,2015).

(5)

Intheexpectedfreeenergy,relativeentropybecomesmutual informationandlog-evidencebecomesthelog-evidenceexpected underthepredictedoutcomes.Ifweassociatethelogpriorover outcomeswithutilityorprior preferences:U(o)=lnP(o), the expectedfreeenergycanalsobeexpressedintermsofepistemic and extrinsic value. This meansextrinsic value corresponds to expectedutilityandcanbeassociatedwiththelog-evidencefor anagent’smodeloftheworldexpectedinthefuture.Epistemic valueissimplytheexpectedinformationgain (mutual informa-tion)affordedtohiddenstatesbyfutureoutcomes(orvice-versa). Afinalre-arrangementshowsthatcomplexitybecomesexpected cost;namely, the KL divergence betweenthe posterior predic-tionsandpriorpreferences;whileaccuracybecomestheaccuracy, expectedunderpredictedoutcomes(i.e.negativeambiguity).This lastequalityshowshowexpectedfreeenergycanbeevaluated rel-ativelyeasily:itisjustthedivergencebetweenthepredictedand preferredoutcomes,minustheambiguity(i.e.,entropy)expected underpredictedstates.

Insummary,expectedfreeenergyisdefinedinrelationtoprior beliefsaboutfutureoutcomes.Thesedefinetheexpectedcostor complexityandcompletethegenerativemodel.Itisthese pref-erencesthatlendinferenceandactionapurposefulorpragmatic (goaldirected)aspect.Thereareseveralusefulinterpretationsof expectedfreeenergythatappealto(andcontextualise)established constructs.Forexample,maximisingepistemicvalueisequivalent tomaximising(expected)Bayesiansurprise(Schmidhuber,1991; IttiandBaldi,2009),whereBayesiansurpriseistheKLdivergence betweenposteriorandpriorbeliefs.Thiscanalsobeinterpretedin termsoftheprincipleofmaximummutualinformationor min-imumredundancy(Barlow,1961; Linsker,1990;Olshausen and Field,1996; Laughlin, 2001).This is becauseepistemicvalue is themutualinformationbetweenhiddenstatesandobservations. Inotherwords,itreportsthereductioninuncertaintyabout hid-denstatesaffordedbyobservations.BecausetheKLdivergence(or informationgain)cannotbelessthanzero,itdisappearswhenthe (predictive)posteriorisnotinformedbynewobservations. Heuris-tically,thismeansepistemicpolicieswillsearchoutobservations thatresolveuncertaintyaboutthestateoftheworld(e.g.,foraging tolocateaprey).However,whenthereisnoposterioruncertainty –andtheagentisconfidentaboutthestateoftheworld–there canbenofurtherinformationgainandepistemicvaluewillbethe sameforallpolicies.

Whentherearenopreferences,themostlikelypolicies max-imise uncertainty or expected information over outcomes (i.e., keepoptionsopen),inaccordwiththemaximumentropy prin-ciple(Jaynes,1957);whileminimisingtheentropyofoutcomes, giventhestate.Heuristically,thismeansagentswilltrytoavoid uninformative(low entropy)outcomes(e.g.,closing one’seyes), whileavoidingstatesthatproduceambiguous(highentropy) out-comes(e.g.,anoisyrestaurant)(Schwartenbecketal.,2013).This resolutionofuncertaintyiscloselyrelatedtosatisfyingartificial curiosity(Schmidhuber,1991;StillandPrecup,2012)andspeaks tothevalueofinformation(Howard,1966).Itisalsoreferredtoas intrinsicvalue:see(Bartoetal.,2004)fordiscussionofintrinsically motivatedlearning.Epistemicvaluecanberegardedasthedrive fornoveltyseekingbehaviour(Wittmannetal.,2008;Krebsetal., 2009;Schwartenbecketal.,2013),inwhichweanticipatethe res-olutionofuncertainty(e.g.,openingabirthdaypresent).Seealso (Bartoetal.,2013).

Theexpectedcomplexityorcostisexactlythesamequantity minimisedinrisksensitiveorKLcontrol(Klyubinetal.,2005;van denBroeketal.,2010),andunderpinsrelated(freeenergy) formu-lationsofboundedrationalitybasedoncomplexitycosts(Braun etal.,2011;OrtegaandBraun,2013).Inotherwords,minimising expectedcomplexityrendersbehaviourrisk-sensitive,while max-imisingexpectedaccuracyrendersbehaviourambiguity-sensitive.

Althoughtheaboveexpressionsappearcomplicated,expected freeenergycanbeexpressedinacompactandsimpleforminterms ofthegenerativemodel:

(6)

Thetwotermsintheexpressionforexpectedfreeenergy repre-sentriskandambiguitysensitivecontributionsrespectively,where utilityisavectorofpreferencesoveroutcomes.Thedecomposition ofexpectedfreeenergyintermsofexpectedcostandambiguity lendsaformalmeaningtoriskandambiguity:riskistherelative entropyoruncertaintyaboutoutcomes,inrelationtopreferences, whileambiguityistheuncertaintyaboutoutcomesinrelationto thestateoftheworld.Thisislargelyconsistentwiththeuseofrisk andambiguityineconomics(KahnemanandTversky,1979;Zak, 2004;KnutsonandBossaerts,2007;Preuschoffetal.,2008),where ambiguityreflectsuncertaintyaboutthecontext(e.g.,whichlottery iscurrentlyinplay).

Insummary,theaboveformalismsuggeststhatexpectedfree energy can be carved in two complementary ways: it can be decomposed into a mixture of epistemic and extrinsic value, promotingexplorative,novelty-seekingandexploitative, reward-seekingbehaviourrespectively.Equivalently,minimisingexpected freeenergycanbeformulatedasminimisingamixtureofexpected costorriskandambiguity.Thiscompletesourdescriptionoffree energy.Wenowturntobeliefupdatingthatisbasedonminimising freeenergyunderthegenerativemodeldescribedabove.

2.4. Beliefupdating

Beliefupdatingmediatesinferenceandlearning,where infer-encemeansoptimisingexpectationsabouthiddenstates(policies andprecision),whilelearningreferstooptimisingmodel param-eters.Thisoptimisationentailsfindingthesufficientstatisticsof posteriorbeliefsthatminimisevariationalfreeenergy.These solu-tionsare(seeAppendixA):

(7)

Fornotationalsimplicity,wehaveused:B =

B(()),B0

=

C,

D=B

0s0,=1/and0=(

Usually,invariationalBayes,onewoulditeratetheabove self-consistent equations until convergence. However, we can also obtainthesolutioninarobustandbiologicallymoreplausible fash-ionbyusingagradientdescentonfreeenergy(seeFristonetal., underreview):Solvingtheseequationsproducesposterior expec-tationsthatminimisefreeenergytoprovideBayesianestimates ofhiddenvariables.Thismeansthatexpectationschangeover sev-eraltimescales:afasttimescalethatupdatesposteriorbeliefsabout hiddenstatesaftereachobservation(tominimisefreeenergyover peristimulustime)andaslowertimescalethatupdatesposterior beliefsasnewobservationsaresampled(tomediateevidence accu-mulationoverobservations);seealso(Pennyetal.,2013).Finally,at theendofeachsequenceofobservations(i.e.,trialofobservation epochs)theexpected(concentration)parametersareupdatedto mediatelearningovertrials.Theseupdatesareremarkablysimple andhaveintuitive(neurobiological)interpretations:

Updatinghiddenstatescorrespondtostateestimation,under each policy. Because each expectation is informed by expecta-tionsaboutpastandfuturestates,thisschemehastheformofa Bayesiansmootherthatcombines(empirical)priorexpectations abouthiddenstateswiththelikelihoodofthecurrentobservation. Havingsaidthis,theschemedoesnotuseconventionalforwardand backwardsweeps,becauseallfutureandpaststatesareencoded explicitly.Inotherwords,representationsalwaysrefertothesame hiddenstateatthesametimeinrelationtothestartofthetrial –notinrelationtothecurrenttime.Thismayseem counterin-tuitivebutthisformofspatiotemporal(placeandtime)encoding finessesbeliefupdatingconsiderablyandhasadegreeof plausibil-ityinrelationtoempiricalfindings,asdiscussedelsewhere(Friston andBuzsaki,2016).

Thepolicyupdatesarejustasoftmaxfunctionoftheirlog prob-ability,which hasthree components:aprior basedonprevious experience,the(posterior) freeenergy basedonpastoutcomes andtheexpected(prior)freeenergybasedonpreferencesabout futureoutcomes.Notethatpriorbeliefsaboutpoliciesinthe gener-ativemodelaresupplementedorinformedbythe(posterior)free energybasedonoutcomes.Becausehabitsarejustanother pol-icy,thearbitrationamonghabitsand(sequential)policiesrestson theirposteriorprobability,whichiscloselyrelatedtothe propos-alsin(Dawetal.,2005;Leeetal.,2014)butintroducesariskand ambiguitytrade-offinpolicyselection(FitzGeraldetal.,2014). Pol-icyselectionalsoentailstheoptimisationofexpecteduncertainty orprecision.Thisisexpressedaboveintermsofthetemperature (inverseprecision)ofposteriorbeliefsaboutprecision:ˇ=1/. Onecanseethattemperatureincreaseswithexpectedfreeenergy. In otherwords,policiesthat,onaverage, have ahighexpected freeenergywillinfluenceposteriorbeliefsaboutpolicieswithless precision.

Interestingly,theupdatestotemperature(andimplicitly preci-sion)aredeterminedbythedifferencebetweentheexpectedfree energyunderposteriorbeliefsaboutpoliciesandtheexpectedfree energyunderpriorbeliefs.Thisendorsesthenotionofreward pre-dictionerrors asanexplanation fordopamineresponses; inthe sensethat ifposterior beliefs based upon current observations reduce theexpected free energy, relative toprior beliefs, then precisionwillincrease(FitzGeraldetal.,2015a,2015b).Thiscan berelatedtodopaminedischargesthathavebeeninterpretedin termsofchangesinexpectedreward(SchultzandDickinson,2000; Fiorilloetal.,2003).Theroleoftheneuromodulatordopaminein encodingprecisionisalsoconsistentwithitsmultiplicativeeffect inthesecondupdate–tonuancetheselectionamongcompeting policies(Fiorilloetal.,2003;Franketal.,2007;Humphriesetal., 2009,2012;SolwayandBotvinick,2012;MannellaandBaldassarre, 2015).Wewillreturntothislater.

Finally,theupdatesfortheparametersbearamarked resem-blancetoclassicalHebbianplasticity(AbbottandNelson,2000).

The transitionor connectivity updates comprisetwo terms:an associative term that is a digamma function of the accumu-latedcoincidenceofpast(postsynaptic)andcurrent(presynaptic) states (orobservations underhidden causes)and a decay term that reduceseach connectionas thetotal afferent connectivity increases.Theassociativeanddecaytermsarestrictlyincreasing but saturating functions of theconcentration parameters. Note that theupdates for the (connectivity) parameters accumulate coincidencesovertimebecause,unlikehiddenstates,parameters are timeinvariant. Furthermore,theparameters encoding state transitions haveassociativeterms thataremodulated bypolicy expectations.Inadditiontothelearningofcontingenciesthrough theparameters ofthetransitionmatrices, thevectorsencoding beliefsabouttheinitialstateandselectedpolicyaccumulate evi-dencebysimplycountingthenumberoftimestheyoccur.Inother words,ifaparticularstateorpolicyisencounteredfrequently,it willcometodominateposteriorexpectations.Thismediates con-textlearning(intermsoftheinitialstate)andhabitlearning(interms ofpolicyselection).Inpractice,thelearningupdatesareperformed attheendofeachtrialorsequenceofobservations.Thisensures thatlearningbenefitsfrominferred(postdicted)states,after ambi-guityhasbeenresolvedthroughepistemicbehaviour.Forexample, theagentcanlearnabouttheinitialstate,eveniftheinitialcues werecompletelyambiguous.

2.5. Summary

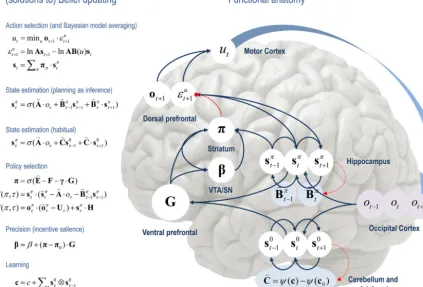

By assuming a generic (Markovian) form for the generative model,itisfairlyeasytoderiveBayesianupdatesthatclarifythe relationshipsbetweenperception,policyselection,precisionand action–andhowthesequantitiesshapebeliefsabouthiddenstates oftheworldand subsequentbehaviour.In brief,theagentfirst infersthehiddenstatesundereachmodelorpolicythatit enter-tains.Itthenevaluatestheevidenceforeachpolicybasedupon priorbeliefsorpreferencesaboutfutureoutcomes.Having opti-misedtheprecisionorconfidenceinbeliefsaboutpolicies,they areusedtoformaBayesianmodelaverageofthenextoutcome, whichisrealisedthroughaction.Theanatomyoftheimplicit mes-sagepassingis notinconsistentwithfunctionalanatomyin the brain:see(Fristonetal.,2014)andFigs.1and2.Fig.2reproduces the (solutions to) belief updating and assigns them to plausi-blebrainstructures.Thisfunctionalanatomyrestsonreciprocal messagepassingamongexpectedpolicies(e.g.,inthestriatum) andexpectedprecision(e.g.,inthesubstantianigra).Expectations aboutpoliciesdependuponexpectedoutcomesandstatesofthe world(e.g.,intheprefrontalcortex(Mushiakeetal.,2006)and hip-pocampus(Pezzuloetal.,2014;PezzuloandCisek,2016;Stoianov etal.,2016)).Crucially,thisschemeentailsreciprocalinteractions betweentheprefrontalcortexandbasalganglia(BotvinickandAn, 2008;Pennartz etal.,2011; Verschureet al.,2014);in particu-lar,selectionofexpected(motor)outcomesbythebasalganglia (MannellaandBaldassarre,2015).Inthenextsection,weconsider theformalrelationshipsbetweenactiveinferenceandconventional schemesbaseduponvaluefunctions.

3. RelationshiptoBellmanformulations

Fig.2.OverviewofbeliefupdatesfordiscreteMarkovianmodels:theleftpanelliststhesolutionsinthemaintext,associatingvariousupdateswithaction,perception,policy selection,precisionandlearning.Therightpanelassignsthevariables(sufficientstatisticsorexpectations)tovariousbrainareastoillustratearoughfunctionalanatomy –impliedbytheformofthebeliefupdates.Observedoutcomesaresignedtovisualrepresentationsintheoccipitalcortex.Stateestimationhasbeenassociatedwiththe hippocampalformationandcerebellum(orparietalcortexanddorsalstriatum)forplanningandhabitsrespectively(EverittandRobbins,2013).Theevaluationofpolicies, intermsoftheir(expected)freeenergy,hasbeenplacedintheventralprefrontalcortex.Expectationsaboutpoliciesperseandtheprecisionofthesebeliefshavebeen assignedtostriatalandventraltegmentalareastoindicateaputativerolefordopamineinencodingprecision.Finally,beliefsaboutpoliciesareusedtocreateBayesianmodel averagesoffuturestates(overpolicies)–thatarefulfilledbyaction.Thebluearrowsdenotemessagepassing,whilethesolidredlineindicatesamodulatoryweightingthat implementsBayesianmodelaveraging.Thebrokenredlinesindicatetheupdatesforparametersorconnectivity(inbluecircles)thatdependonexpectationsabouthidden states(e.g.,associativeplasticityinthecerebellum).Pleaseseetheappendixforanexplanationoftheequationsandvariables.Thelargebluearrowcompletestheaction perceptioncycle,renderingoutcomesdependentuponaction.(Forinterpretationofthereferencestocolourinthisfigurelegend,thereaderisreferredtothewebversion ofthisarticle.)

1952;Howard,1960).Wecanexpressdynamicprogrammingusing theabovenotationasfollows:

(8)

Thefirstpairofequationsrepresentsthetwostepsofdynamic programming.Thesecondsetofequationsexpressestheoptimal policyintermsofourgenerativemodel,whereBsdenotesthe col-umnofthematrixencodingthetransitionsfromstates.Inbrief,the optimalpolicyreturnstheactionthatmaximisesutilityU(s)∈U

plus a value-function of states V(s)∈V. The value-function is thenevaluatedundertheoptimalpolicy,untilconvergence.The value-functionrepresentstheexpected utility(cf.,prior prefer-ence)integratedoverfuturestates.Thecloserelationshipbetween dynamicprogrammingandbackwardsinductionishighlightedby thefinalexpressionforvalue,whichiseffectivelytheutilityover statespropagatedbackwardsintimebytheoptimal(habitual) tran-sitionmatrix.

Dynamicprogrammingsupposesthatthereisanoptimalaction thatcanbetakenfromeverystate,irrespectiveofthecontextor timeofaction.Thisis,ofcourse,thesameassumptionimplicitin habitlearning− andwe mightexpecttoseea correspondence betweenthestatetransitionsencodedbyC=B0andB (wewill returntothisinthelastsection).However,thiscorrespondencewill onlyarisewhenthe(Bellman)assumptionsofdynamic program-mingorbackwardsinductionhold;i.e.,whenstatesareobserved unambiguously,suchthato=sandU(o)=U(s)∈U.Inthesecases, onecanalsousevariationalbeliefupdatingtoidentifythebest actionfromanystate.Thisistheactionassociatedwiththepolicy thatminimisesexpectedfreeenergy,startingfromanystate:

[image:10.612.84.507.63.350.2]Fig.3.Thegenerativemodelusedtosimulateforaginginathree-armmaze(insertontheupperright).Thismodelcontainsfourcontrolstatesthatencodemovementto oneoffourlocations(threearmsandacentrallocation).Thesecontrolthetransitionprobabilitiesamonghiddenstatesthathaveatensorproductformwithtwofactors: thefirstisplace(oneoffourlocations),whilethesecondisoneoftwocontexts.Thesecorrespondtothelocationofrewarding(red)outcomesandtheassociatedcues(blue orgreencircles).Eachoftheeighthiddenstatesgeneratesanobservableoutcome,wherethefirsttwohiddenstatesgeneratethesameoutcomethatjusttellstheagent thatitisatthecenter.Someselectedtransitionsareshownasarrows,indicatingthatcontrolstatesattracttheagenttodifferentlocations,whereoutcomesaresampled. Theequationsdefinethegenerativemodelintermsofitsparameters(A,B),whichencodemappingsfromhiddenstatestooutcomesandstatetransitionsrespectively.The lowervectorcorrespondstopriorpreferences;namely,theagentexpectstofindareward.Here,⊗denotesaKroneckertensorproduct.(Forinterpretationofthereferences tocolourinthisfigurelegend,thereaderisreferredtothewebversionofthisarticle.)

Thiseffectivelycomposesastate-actionpolicybypickingthe actionunderthebestpolicyfromeachstate(assumingthecurrent stateisknown).Thekeypointhereisthatdynamicprogrammingis aspecialcaseofthisvariationalscheme.Onecanseethisby substi-tutingtheexpressionforvalueaboveintothefirststepofdynamic programming.Thisisknownasdirectpolicyiteration(Williams, 1992;Baxteretal.,2001).Theensuingpolicyiterationschemecan nowbeexpressed,notintermsofvalue,butin termsoffuture states.

(10)

Thisisformallyequivalenttothevariationalstate-action pol-icywithtwodifferences.First,thepolicyiterationschemesimply maximisesexpectedutility,asopposedtoexpectedfreeenergy. Thismeanstheriskandambiguitytermsdisappearandfreeenergy reducestoexpectedutility.Theseconddifferencepertainstothe recursiveiterationoffuturestates:activeinferenceusesvariational updatestoimplementBayesiansmoothing,whereasthebackward inductionschemeimputesfuturestatesbyrecursiveapplicationof theoptimaltransitionmatrix.

Onemightquestiontherelativemeritsofiterativelyevaluating thevalue-functionofstates(Eq.(8)),asopposedtothestatesper se(Eq,(10)).Clearly,ifonewantstodealwithriskandambiguity, then an evaluation of the states (and theirentropy) is neces-sary.Inotherwords,ifonewantstoaugmentconventionalutility functionswith riskand ambiguityterms, it becomes necessary toevaluatebeliefs aboutfuture states(asin Eq.(10)).Thishas aprofound implicationforschemes (suchasdynamic program-ming,backwardsinductionandreinforcementlearning)basedon valuefunctions.Theseschemesare,inessence,belief-freebecause theconstructionofvaluefunctionsprecludesacontributionfrom beliefsaboutthefuture(unlessoneusesabeliefMDP).Thisisa keydifferencebetween(belief-based)activeinferenceand (belief-free)schemesbasedupontheBellmanassumptions.Insummary, belief-freeschemesarelimitedtosituationsinwhichthereisno ambiguityabouthiddenstates(whicharedifficulttoconceivein mostinterestingorreal-worldsettings).Wewillseeanexampleof thislimitationinthenextsection.Thiscompletesourtheoretical treatmentofactiveinferenceandlearning.Inthelastsection,we usesimulationstorevisitsomekeyconceptsabove.

4. Simulationsofforaging

[image:11.612.93.518.55.326.2]termsofresponseselicitedinreinforcementlearningparadigmsby

unconditioned(US)andconditioned(CS)stimuli.Strictlyspeaking, ourparadigmisinstrumentalandthecueisadiscriminative stim-ulus;however,wewillretainthePavloviannomenclature,when relatingprecisionupdatestodopaminergicdischarges.

4.1. Thesetup

Anagent(e.g.,arat)startsinthecenterofaT-maze,whereeither therightorleftarmsarebaitedwithareward(US).Thelowerarm containsadiscriminativecue(CS)thattellstheanimalwhetherthe rewardisintheupperrightorleftarm.Crucially,theagentcanonly maketwomoves.Furthermore,theagentcannotleavethebaited armsaftertheyareentered.Thismeansthattheoptimalbehaviour istofirstgotothelowerarmtofindwheretherewardislocated andthenretrievetherewardatthecuedlocation.

IntermsofaMarkovdecisionprocess,therearefourcontrol statesthatcorrespondtovisiting,orsampling,thefourlocations (thecenterandthreearms).Forsimplicity,weassumethateach actiontakestheagenttotheassociatedlocation(asopposedto movinginaparticulardirectionfromthecurrentlocation).This isanalogous toplace-basednavigationstrategies thoughttobe mediatedbythehippocampus(Moseretal.,2008).Thereareeight hiddenstates:fourlocationstimes,twocontexts(right andleft reward)andsevenpossibleoutcomes.Theoutcomescorrespond tobeinginthecenterofthemazeplusthe(two)outcomesateach ofthe(three)armsthataredeterminedbythecontext(therightor leftarmismorerewarding).

Havingspecifiedthestate-space,itisnownecessaryto spec-ifythe(A,B)matricesencodingcontingencies.Theseareshownin

Fig.3,wheretheAmatrixmapsfromhiddenstatestooutcomes, deliveringanambiguous cueatthecenter (first)locationand a definitivecueatthelower(fourth)location.Theremaining loca-tionsprovideareward(ornot)withprobabilityp=98%depending uponthecontext.TheB(u)matricesencodeaction-specific transi-tions,withtheexceptionofthebaited(secondandthird)locations, whichare(absorbing)hiddenstatesthattheagentcannotleave.

Onecouldconsiderlearningcontingenciesbyupdatingtheprior concentrationparameters(a,b)ofthetransitionmatricesbutwe willassumetheagentknows(i.e.,hasveryprecisebeliefsabout) thecontingencies.Thiscorrespondstomakingtheprior concentra-tionparametersverylarge.Conversely,wewillusesmallvaluesof (c,d)toenablehabitandcontextlearningrespectively.The param-etersencodingpriorexpectationsaboutpolicies(e)willbeused topreclude(thissection)orpermit(nextsection)theselectionof habitualpolicies.PreferencesinthevectorU=lnP(o)encodethe utilityofoutcomes.Here,theutilitiesofarewardingand unreward-ingoutcomewere3and−3respectively(andzerootherwise).This means,theagentexpectstoberewardedexp(3)≈20timesmore thanexperiencinganeutraloutcome.Notethatutilityisalways rel-ativeandhasaquantitativemeaningintermsofpreferredstates. Thisisimportantbecauseitendowsutilitywiththesamemeasure asinformation;namely,nats(i.e.,unitsofinformationorentropy basedonnaturallogarithms).Thishighlightsthecloseconnection betweenvalueandinformation.

Having specifiedthe state-spaceand contingencies,one can solvethebeliefupdatingequations(Eq.(7))tosimulatebehaviour. The(concentration)parametersofthehabitswereinitialisedtothe sumofalltransitionprobabilities:c=

uB(u).Priorbeliefsabout theinitialstatewereinitialisedtod=8forthecentrallocationfor eachcontextandzerootherwise.Finally,priorbeliefsabout poli-cieswereinitialisedtoe=4withtheexceptionofthehabit,where e=0.Theseconcentrationparameterscanberegardedasthe num-beroftimeseachstate,transitionorpolicyhasbeenencountered inprevioustrials.Fig.4summarisesthe(simulated)behaviouraland physiologi-calresponsesover32successivetrialsusingaformatthatwillbe adoptedinsubsequentfigures.Eachtrialcomprisestwoactions followinganinitialobservation.Thetoppanelshowstheinitial states oneach trial(ascoloured circles)and subsequentpolicy selection(inimageformat)over the11policiesconsidered.The first10(allowable)policiescorrespondtostayingatthecenterand thenmovingtoeachofthefourlocations,movingtotheleftor rightarmandstayingthere,ormovingtothelowerarmandthen movingtoeachofthefourlocations.The11thpolicycorresponds toahabit(i.e.,state-actionpolicy).Theredlineshowsthe poste-riorprobabilityofselectingthehabit,whichiseffectivelyzeroin thesesimulationsbecausewesetitsprior(concentration parame-ter)tozero.Thesecondpanelreportsthefinaloutcomes(encoded bycolouredcircles)andperformance.Performanceisreportedin termsofpreferredoutcomes,summedovertime(blackbars)and reactiontimes(cyandots).Notethatbecausepreferencesarelog probabilitiestheyarealwaysnegative–andthebestoutcomeis zero.2Thereactiontimesherearebasedupontheprocessingtime

inthesimulations(usingtheMatlabtic-tocfacility)andareshown afternormalisationtoameanofzeroandstandarddeviationofone. Inthisexample,thefirstcoupleoftrialsalternatebetweenthe twocontextswithrewardsontherightandleft.Afterthis,the con-text(indicatedbythecue)remainedunchanged.Forthefirst20 trials,theagentselectsepistemicpolicies,firstgoingtothelower armandthenproceedingtotherewardlocation(i.e.,leftforpolicy #8andrightforpolicy#9).Afterthis,theagentbecomes increas-inglyconfident aboutthecontext andstartstovisitthereward locationdirectly.Thedifferencesinperformance betweenthese (epistemicandpragmatic)behavioursarerevealedinthesecond panelasadecreaseinreactiontimeandanincreaseinthe aver-ageutility.Thisincreasefollowsbecausetheaverageisovertrials andtheagentspendstwotrialsenjoyingitspreferredoutcome, when seeking reward directly – as opposed to one trial when behavingepistemically.Notethatontrial12,theagentreceived anunexpected(null)outcomethatinducesadegreeofposterior uncertaintyaboutwhich policyitwaspursuing.Thisis seenas anon-trivial posteriorprobabilityfor threepolicies:thecorrect (context-sensitive)epistemicpolicyandthebestalternativesthat involvestayinginthelowerarmorreturningtothecenter.

Thethirdpanelshowsasuccessionofsimulatedeventrelated potentialsfollowingeachoutcome.Thesearetherateofchange ofneuronalactivity,encodingtheexpectedprobabilityofhidden states.Thefourthpanelshowsphasicfluctuationsinposterior pre-cisionthatcan beinterpretedin terms ofdopamineresponses. Here,thephasiccomponentofsimulateddopamineresponses cor-respondstotherateofchangeofprecision(multipliedbyeight) andthetoniccomponenttotheprecisionperse(dividedbyeight). Thephasicpartistheprecisionpredictionerror(cf.,reward predic-tionerror:seeEq.(8)).Thesesimulatedresponsesrevealaphasic responsetothecue(CS)duringepistemictrialsthatemergeswith contextlearningoverrepeatedtrials.Thisreflectsanimplicit trans-ferofdopamineresponsesfromtheUStotheCS.Whenthereward (US)isaccesseddirectlythereisaprofoundincreaseinthephasic response,relativetotheresponseelicitedafterithasbeenpredicted bytheCS.

Thefinaltwopanelsshowcontextandhabitlearning:the penul-timatepanelshowstheaccumulatedposteriorexpectationsabout theinitialstateD,whilethelowerpanelsshowtheposterior expec-tationsofhabitualstatetransitions,C.Theimplicitlearningreflects

2Utilitiescanonlybespecifiedtowithinanadditiveconstant(thelog

Fig.4.Simulatedresponsesover32trials:thisfigurereportsthebehaviouraland(simulated)physiologicalresponsesduringsuccessivetrials.Thefirstpanelshows,foreach trial,theinitialstate(asblueandredcirclesindicatingthecontext)andtheselectedpolicy(inimageformat)overthe11policiesconsidered.Thepoliciesareselectedinthe firsttwotrialscorrespondtoepistemicpolicies(#8and#9),whichinvolveexaminingthecueinthelowerarmandthengoingtotheleftorrightarmtosecurethereward (dependingonthecontext).Aftertheagentbecomessufficientlyconfidentthatthecontextdoesnotchange(aftertrial21)itindulgesinpragmaticbehaviour,accessingthe rewarddirectly.Theredlineshowstheposteriorabilityofselectingthehabit,whichiswassettozerointhesesimulations.Thesecondpanelreportsthefinaloutcomes (encodedbycolouredcircles:cyanandblueforrewardingoutcomesintheleftandrightarms)andperformancemeasuresintermsofpreferredoutcomes,summedovertime (blackbars)andreactiontimes(cyandots).Thethirdpanelshowsasuccessionofsimulatedeventrelatedpotentialsfollowingeachoutcome.Thesearetakentobetherate ofchangeofneuronalactivity,encodingtheexpectedprobabilityofhiddenstates.Thefourthpanelshowsphasicfluctuationsinposteriorprecisionthatcanbeinterpreted intermsofdopamineresponses.Thefinaltwopanelsshowcontextandhabitlearning,expressedintermsof(C,D):thepenultimatepanelshowstheaccumulatedposterior beliefsabouttheinitialstate,whilethelowerpanelsshowtheposteriorexpectationsofhabitualstatetransitions.Here,eachpanelshowstheexpectedtransitionsamong theeighthiddenstates(seeFig.3),whereeachcolumnencodestheprobabilityofmovingfromonestatetoanother.Pleaseseemaintextforadetaileddescriptionofthese responses.(Forinterpretationofthereferencestocolourinthisfigurelegend,thereaderisreferredtothewebversionofthisarticle.)

anaccumulationofevidencethattherewardwillbefoundinthe samelocation.Inotherwords,initiallyambiguouspriorsoverthe firsttwohiddenstatescometoreflecttheagent’sexperiencethat italwaysstartsinthefirsthiddenstate.It isthiscontext learn-ingthatunderliesthepragmaticbehaviourinlatertrials.Wetalk aboutcontextlearning(asopposedtoinference)because,strictly speaking,Bayesianupdatestomodelparameters(betweentrials) arereferredtoaslearning,whileupdatestohiddenstates(within trial)correspondtoinference.

[image:13.612.82.525.57.511.2]5. Simulationsoflearning

Thissectionillustratesthedistinctionbetweencontextandhabit

learning.Intheprevioussection,contextlearningenabledmore informedandconfident(pragmatic)behaviourastheagentbecame familiarwithitsenvironment.Inthissection,weconsiderhowthe samecontextlearningcanleadtoperseverationandthereby influ-encereversallearning,whencontingencieschange.Followingthis, weturntohabitlearningandsimulatesomecardinalaspectsof devaluation.Finally,weturntoepistemichabitsandcloseby com-paringanacquiredwithandwithoutambiguousoutcomes.This servestohighlightthedifferencebetweenbelief-basedand belief-freeschemes–andillustratestheconvergenceofactiveinference andbelief-freeschemes,whentheworldisfullyobserved.

5.1. Contextandreversallearning

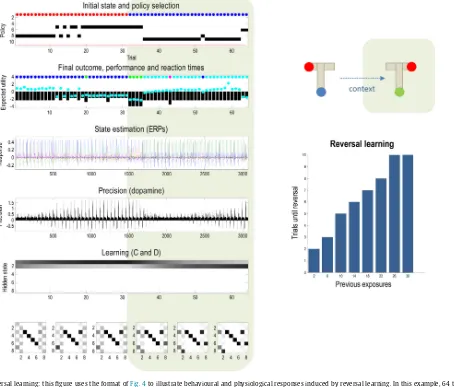

Fig.5usestheformatofFig.4toillustratebehaviouraland phys-iologicalresponsesinducedbyreversallearning.Inthisexample, 64trialsweresimulatedwithaswitchincontexttoa(consistent) rewardlocationfromthelefttotherightarmafter32trials.The upperpanelshows thatafter about16trials theagentis suffi-cientlyconfidentaboutthecontexttogostraighttotherewarding location;therebyswitchingfromanepistemictoapragmatic pol-icy.Priortothisswitch,phasicdopamineresponsestothereward (US)progressivelydiminishand aretransferredtothe discrimi-nativecue(CS)(Fiorilloetal.,2003).Afteradoptingapragmatic policy,dopamineresponsestotheUSdisappearbecausetheyare completelypredictableandaffordnofurtherincreaseinprecision. Crucially,after32trialsthecontextchangesbutthe(pragmatic) policypersists,leadingto4trialsinwhichtheagentgoestothe wronglocation.Afterthis,it revertstoanepistemicpolicyand, afteraperiod ofcontextlearning,adoptsa newpragmatic pol-icy.Behaviouralperseverationofthissortismediatedpurelyby priorbeliefsaboutcontextthataccumulateovertrials.Here,thisis reflectedinthepriorbeliefaboutthehiddenstatesencounteredat thebeginningofeachnewtrial(shownasafunctionoftrialsinthe fifthpanel).Thiscontextlearningisillustratedintherightpanel, whichshowsthenumberofperseverativetrialsbeforereversal,as afunctionofpreviousexposurestotheoriginalcontext.

Notethatthisformofreversallearningreflectschangesinprior expectationsaboutthehiddenstatesgeneratingthefirstoutcome. Thisshouldbecontrastedwithlearningareversalofcontingencies encodedbythestatetransitionparameters,orparameters map-pingfromstates tooutcomes.Learningtheseparameterswould alsoproducereversallearningandanumberofotherphenomena inpsychology;suchaseffectofpartialreinforcement(Delamater andWestbrook,2014).However,inthispaper,wefocuson con-textandhabitlearning;asopposedtocontingencylearning.The abovedemonstrationofreversallearningproceededintheabsence ofhabits.Intheremainingsimulations,weenabledhabitlearning byallowingits(concentration)parametertoaccumulateovertrials.

5.2. Habitformationanddevaluation

Fig.6usesthesameformatasthepreviousfiguretoillustrate habitformationandtheeffectsofdevaluation.Devaluation pro-videsacriticaltestfordissociable(goal-directedorcontingencyand habitualorincentive)learningmechanismsinpsychology(Balleine andDickinson,1998;YinandKnowlton,2006).Theleft-hand pan-elsshowhabitlearningover64trialsinwhichthecontextwasheld constant.Theposteriorprobabilityofthehabitualpolicyisshown intheupperpanel(solidredline),wherethehabitisunderwritten bythestatetransitionsinthelowerpanels.Thissimulationshows thatashabitualtransitionsarelearnt,theposteriorprobabilityof thehabitincreasesuntilitisexecutedroutinely.Inthiscase,the

acquiredhabitcorrespondstoanepistemicpolicy(policy#8),and afterthehabithasbeenacquired,thereisnoopportunityfor prag-maticpolicies.Thismeansthatalthoughthebehaviourisefficient interms ofreactiontimes,thehabithasprecludedexploitative behaviour(Dayanetal.,2006).Thereasonwhythishabithas epis-temiccomponentsisbecauseitwaslearnedunderprior beliefs thatbothcontextswereequallylikely;conversely,ahabitacquired underadifferentpriorcouldbepragmatic.

Onemightaskwhyahabitisselectedoverasequential pol-icythatpredictsthesamebehaviour.Thehabitisselectedbecause it providesa betterexplanation for observedoutcomes. Thisis becausethejointdistributionoversuccessivestatesisencodedby theconcentrationparametersc⊂(seeEq.(6)).Technically,this meansthathabitshavelesscomplexityandfreeenergypath inte-grals.Onecanseethisanecdotallyinthetransitionmatricesonthe lowerleftofFig.6:ifwewereintheseventhstateafterthefirst move,wecanbealmostcertainwestartedinthefirststate. How-ever,underthemodeloftransitionsprovidedbythebestsequential policy(policy#8),theempiricalprioraffordedbyknowingwewere intheseventhstateislessdefinitive(wecouldhavemovedfrom thefirststateorwecouldhavealreadybeenintheseventh).

Duringtheacquisitionofthehabit,thereactiontimesdecrease withmaintainedperformanceand systematicchangesin phasic dopamineresponses(fourthpanel).Animportantcorrelateofhabit learningistheattenuationofelectrophysiologicalresponses(e.g., in the hippocampus). This reflects thefact that the equivalent beliefupdatesforthehabit(e.g.,inthecerebellum,parietalcortex anddorsolateralstriatum(EverittandRobbins,2013)),havebeen deliberatelyomittedfromthegraphics.Thiseffectivetransferof sequentialprocessing(fromhippocampustocerebellarcortex)may provideasimpleexplanationfortheputativetransferinrealbrains duringmemoryconsolidation;forexample,duringsleep(Buzsaki, 1998;Kesner,2000;Pezzuloetal.,2014).

Crucially,afterthehabitwasacquiredtherewardwasdevalued byswitchingthepriorpreferences(attrial48),suchthatthe neu-traloutcomebecamethepreferredoutcome(denotedbythegreen shadedareas).Despitethisswitch,thehabitpersistsand,indeed, reinforcesitselfwithrepeatedexecutions.Therightpanelsreport exactlythesamesimulationwhentherewardsweredevaluedafter 16trials,beforethehabitwasfullyacquired.Inthisinstance,the agentswitches itsbehaviour immediately(beforesamplingthe devaluedoutcome)andsubsequentlyacquiresahabitthatis con-sistentwithitspreferences(comparethetransitionprobabilities inthelowerpanels).Inotherwords,priortohabitformation,goal directedbehaviourissensitivetodevaluation–asensitivitythat islostunderhabitualcontrol.Thesesimulationsdemonstratethe resistanceofhabitualpoliciestodevaluationresultingin subopti-malperformance(butfasterreactiontimes:seesecondpanel).See

Dayanetal.(2006)foradiscussionofhowhabitscanconfound learninginthisway.

5.3. Epistemichabitacquisitionunderambiguity

Fig. 7 illustrates the acquisition of epistemic habits under ambiguous(leftpanels)andunambiguous(rightpanels)outcome contingencies.Inthesesimulations,thecontextswitchesrandomly fromonetrialtothenext.Theleftpanelsshowtherapidacquisition ofanepistemichabitafterabout16trialsofepistemiccue-seeking. Astheagentobservesitsownhabitualbehaviour,theprior proba-bilityofthehabitincreases(dottedredlineintheupperpanel).This priorprobabilityisbaseduponthepolicyconcentration param-eters, e⊂.Thelower panels showthestatetransitions under thehabitualpolicy;properlyenforcingavisittothecuelocation followedbyappropriaterewardseeking.

vari-Fig.5.Reversallearning:thisfigureusestheformatofFig.4toillustratebehaviouralandphysiologicalresponsesinducedbyreversallearning.Inthisexample,64trials weresimulatedwithaswitchincontextfromone(consistent)rewardlocationtoanother.Theupperpanelshowsthatafterabout16trialstheagentissufficientlyconfident aboutthecontexttogostraighttotherewardinglocation;therebyswitchingfromanepistemictoapragmaticpolicy.After32trialsthecontextchangesbutthe(pragmatic) policypersists;leadingto4trialsinwhichtheagentgoestothewronglocation.Afterthis,itrevertstoanepistemicpolicyand,afteraperiodofcontextlearning,adopts anewpragmaticpolicy.Behaviouralperseverationofthissortismediatedpurelybypriorbeliefsaboutcontextthataccumulateovertrials.Thisisillustratedintheright panel,whichshowsthenumberofperseverationsafterreversal,asafunctionofthenumberofpreceding(consistent)trials.

ationalestimate)inthelowerpanels:thesearethesolutionsto Eqs.(9)and(10).Clearly,the‘optimal’policyistogostraightto therewardinglocationineachcontext(orhiddenstate);however, thisisnousewhenoutcomesareambiguousandtheagentdoes notknowwhichcontextitisin.Thismeanstheoptimal(epistemic) state-actionpolicyunderactiveinference(leftpanel)is fundamen-tallydifferentfromtheoptimal(pragmatic)habitunderdynamic programming(rightpanel).Thisdistinction canbedissolvedby makingtheoutcomesunambiguous.Therightpanelsreportthe resultsofanidenticalsimulationwithoneimportantdifference –the outcomesobservedfrom thestartinglocation unambigu-ouslyspecifythecontext.Inthisinstance,allstate-actionpolicies areformallyidentical(althoughtransitionsfromthecuelocation arenotevaluatedunderactiveinference,becausetheyarenever encountered).

5.4. Summary

In summary, these simulations suggest that agents should acquireepistemic habits – and can only do so through belief-based learning. There is nothing remarkable about epistemic

habits;theyareentirelyconsistentwiththeclassicalconception ofhabits–intheanimallearningliterature–aschainsof stimulus-response associations. The key aspect hereis that they can be acquired(autodidactically)viaobservingepistemicgoal-directed behaviour.

6. Conclusion

Wehavedescribedanactiveinferenceschemefordiscrete state-spacemodelsofchoicebehaviourthatissuitableformodellinga varietyofparadigmsandphenomena.Althoughgoal-directedand habitualpoliciesareusuallyconsideredintermsofmodel-based

[image:15.612.75.529.62.449.2]Fig.6. Habitformationanddevaluation:thisfigureusesthesameformatasthepreviousfiguretoillustratehabitformationandtheeffectsofdevaluation.Theleftpanels showhabitlearningover64trialsinwhichthecontextwasheldconstant.Theposteriorprobabilityofthehabitualpolicyisshownintheupperpanel(solidredline),where thehabitisunderwrittenbythestatetransitionsshowninthelowerpanels.Thesimulationshowsthatasthehabitualtransitionsarelearnt,theposteriorprobabilityofthe habitincreasesuntilitisexecutedroutinely.Afterthehabithadbeenacquired,wedevaluedtherewardbyswitchingthepriorpreferencessuchthattheneutraloutcome becamethepreferredoutcome(denotedbythegreenshadedareas).Despitethispreferencereversal,thehabitpersists.Therightpanelsreportthesamesimulationwhenthe rewardwasdevaluedafter16trials,beforethehabitwasfullyacquired.Inthisinstance,theagentswitchesimmediatelytothenewpreferenceandsubsequentlyacquires ahabitthatisconsistentwithitspreferences(comparethetransitionprobabilitiesinthelowerpanels).(Forinterpretationofthereferencestocolourinthisfigurelegend, thereaderisreferredtothewebversionofthisarticle.)

Totheextentthatoneacceptsthevariational(activeinference) formulationofbehaviour,thereareinterestingimplicationsforthe distinctionbetweenhabitualand goal-directedbehaviour.Ifwe associatemodel-freelearningwithhabit-learning,thenmodel-free learningemergesfrommodel-based behaviour.In otherwords, model-basedplanningengendersand contextualisesmodel-free learning.Inthissense,activeinferencesuggeststherecanbeno model-freeschemethatislearnedautonomouslyordivorcedfrom goal-directed(model-based)behaviour.Therearefurther impli-cationsfortheroleofvalue-functionsandbackwardsinduction instandardapproachestomodel-basedplanning.Crucially, varia-tionalformulationsdonotrefertovalue-functionsofstates,even whenoptimisinghabitual(state-action)policies.Putsimply, learn-inginactiveinferencecorrespondstooptimisingtheparameters ofagenerativemodel.Inthisinstance,theparameterscorrespond tostatetransitionsthatleadtovaluable(preferred)states.Atno pointdo weneedtolearnanintermediaryvalue-functionfrom whichthesetransitionsarederived.Insum,theimportant distinc-tionbetweengoal-directedandhabitualbehaviourmaynotbethe distinctionbetweenmodel-basedandmodel-freebutthe

distinc-tionbetweenselectingpoliciesthatareandarenotsensitiveto contextorambiguity;i.e.belief-basedversusbelief-free.

[image:16.612.34.547.58.436.2]Fig.7. Epistemichabitacquisitionunderambiguity:thisfigureusesthesameformatasFig.6toillustratetheacquisitionofepistemichabitsunderambiguous(leftpanels) andunambiguous(rightpanels)outcomes.Theleftpanelsshowtherapidacquisitionofanepistemichabitafterabout16trialsofepistemiccue-seeking,whenthecontext switchesrandomlyfromonetrialtothenext.Thelowerpanelsshowthestatetransitionsunderthehabitualpolicy;properlyenforcingavisittothecuelocationfollowedby appropriaterewardseeking.Thispolicyshouldbecontrastedwiththeso-calledoptimalpolicyprovidedbydynamicprogramming(andtheequivalentvariationalestimate) inthelowerpanels.Theoptimal(epistemic)state-actionpolicyisfundamentallydifferentfromtheoptimal(pragmatic)habitunderdynamicprogramming.Thisdistinction canbedissolvedbymakingtheoutcomesunambiguous.Therightpanelsreporttheresultsofanidenticalsimulation,whereoutcomesobservedfromthestartinglocation specifythecontextunambiguously.

Attheleveloftheparticular(neuronal)processtheorydescribed inthispaper,therearemanypredictionsabouttheneuronal cor-relatesofperception,evaluation,policyselectionandtheencoding ofuncertaintyassociatedwithdopaminergicdischarges.For exam-ple,thekeydifferencebetweenexpectedfreeenergyandvalueis theepistemiccomponentorinformationgain.Thismeansthata strongprediction(whichtoourknowledgehasnotyetbeentested) isthatamildlyaversiveoutcomethatreducesuncertaintyaboutthe experimentalorenvironmentalcontextwillelicitapositivephasic dopaminergicresponse.

Disclosurestatement

Theauthorshavenodisclosuresorconflictofinterest.

Acknowledgements

KJF is funded by the Wellcome Trust (Ref: 088130/Z/09/Z). PhilippSchwartenbeckisarecipientofaDOCFellowshipofthe Aus-trianAcademyofSciencesattheCentreforCognitiveNeuroscience; UniversityofSalzburg.GPgratefullyacknowledgessupportofHFSP (YoungInvestigatorGrantRGY0088/2014).

AppendixA.

[image:17.612.44.565.58.414.2]Freeenergyanditsexpectationaregivenby:

Here,B =

B(()),B0

=

CandB

0s0 =

D.B(d)isthebeta func-tionofthecolumnvectordandtheremainingvariablesare:

Usingthestandardresult:

∂

dB(d)=B(d)D,wecandifferentiate thevariationalfreeenergywithrespecttothesufficientstatistics (withaslightabuseofnotationandusing

∂

sF:=∂

F(,)/∂

s):Finally,the solutionsto theseequations givethevariational updatesinthemaintext(Eq.(7)).

References

Abbott,L.F.,Nelson,S.,2000.Synapticplasticity:tamingthebeast.Nat.Neurosci.3, 1178–1183.

Alagoz,O.,Hsu,H.,Schaefer,A.J.,Roberts,M.S.,2010.Markovdecisionprocesses:a toolforsequentialdecisionmakingunderuncertainty.Med.Decis.Making30 (4),474–483.

Attias,H.,2003.Planningbyprobabilisticinference.Proceedingsofthe9th InternationalWorkshoponArtificialIntelligenceandStatistics. Averbeck,B.B.,2015.Theoryofchoiceinbandit:informationsamplingand

foragingtasks.PLoSComput.Biol.11(3),e1004164.

Balleine,B.W.,Dickinson,A.,1998.Goal-directedinstrumentalaction:contingency andincentivelearningandtheircorticalsubstrates.Neuropharmacology37 (4-5),407–419.

Balleine,B.W.,Ostlund,S.B.,2007.Stillatthechoice-point:actionselectionand initiationininstrumentalconditioning.Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci.1104,147–171. Barlow,H.,1961.Possibleprinciplesunderlyingthetransformationsofsensory

messages.In:Rosenblith,W.(Ed.),SensoryCommunication.MITPress, Cambridge,MA,pp.217–234.

Barto,A.,Singh,S.,Chentanez,N.,2004.Intrinsicallymotivatedlearningof hierarchicalcollectionsofskills.In:Proceedingsofthe3rdInternational ConferenceonDevelopmentandLearning(ICDL2004),SalkInstitute,San Diego.

Barto,A.,Mirolli,M.,Baldassarre,G.,2013.Noveltyorsurprise?Front.Psychol.,4. Baxter,J.,Bartlett,P.L.,Weaver,L.,2001.Experimentswithinfinite-horizon:

policy-gradientestimation.J.Artif.Intell.Res.15,351–381.

Beal,M.J.,2003.VariationalAlgorithmsforApproximateBayesianInference.PhD. Thesis.UniversityCollegeLondon.

Bellman,R.,1952.Onthetheoryofdynamicprogramming.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U. S.A.38,716–719.

Bonet,B.,Geffner,H.,2014.Belieftrackingforplanningwithsensing:width, complexityandapproximations.J.Artif.Intell.Res.50,923–970.

Botvinick,M.,An,J.,2008.Goal-directeddecisionmakinginprefrontalcortex:a computationalframework.Adv.NeuralInf.Process.Syst.(NIPS).

Botvinick,M.,Toussaint,M.,2012.Planningasinference.TrendsCogn.Sci.16(10), 485–488.

Braun,D.A.,Ortega,P.A.,Theodorou,E.,Schaal,S.,2011.Pathintegralcontroland boundedrationality.AdaptiveDynamicProgrammingAndReinforcement Learning(ADPRL),2011IEEESymposiumOn,Paris,IEEE.

Brown,L.D.,1981.Acompleteclasstheoremforstatisticalproblemswith finite-samplespaces.Ann.Stat.9(6),1289–1300.

Buzsaki,G.,1998.Memoryconsolidationduringsleep:aneurophysiological perspective.J.SleepRes.7(Suppl.1),17–23.

Cooper,G.,1988.Amethodforusingbeliefnetworksasinfluencediagrams. ProceedingsoftheConferenceonUncertaintyinArtificialIntelligence. Daw,N.D.,Niv,Y.,Dayan,P.,2005.Uncertainty-basedcompetitionbetween

prefrontalanddorsolateralstriatalsystemsforbehavioralcontrol.Nat. Neurosci.8(12),1704–1711.

Daw,N.D.,Gershman,S.J.,Seymour,B.,Dayan,P.,Dolan,R.J.,2011.Model-based influencesonhumans’choicesandstriatalpredictionerrors.Neuron69(6), 1204–1215.

Dayan,P.,Niv,Y.,Seymour,B.,Daw,N.D.,2006.Themisbehaviorofvalueandthe disciplineofthewill.NeuralNetw.19(8),1153–1160.

Delamater,A.R.,Westbrook,R.F.,2014.Psychologicalandneuralmechanismsof experimentalextinction:aselectivereview.Neurobiol.LearnMem.108, 38–51.

Dezfouli,A.,Balleine,B.W.,2013.Actions,actionsequencesandhabits:evidence thatgoal-directedandhabitualactioncontrolarehierarchicallyorganized. PLoSComput.Biol.9(12),e1003364.

Dolan,R.J.,Dayan,P.,2013.Goalsandhabitsinthebrain.Neuron80(2),312–325. Duff,M.,2002.OptimalLearning:ComputationalProcedureforBayes-Adaptive

MarkovDecisionProcesses.Amherst.

Everitt,B.J.,Robbins,T.W.,2013.Fromtheventraltothedorsalstriatum:devolving viewsoftheirrolesindrugaddiction.Neurosci.Biobehav.Rev.37(9,PartA), 1946–1954.

Fiorillo,C.D.,Tobler,P.N.,Schultz,W.,2003.Discretecodingofrewardprobability anduncertaintybydopamineneurons.Science299(5614),1898–1902. FitzGerald,T.,Dolan,R.,Friston,K.,2014.Modelaveraging,optimalinference,and

habitformation.Front.Hum.Neurosci.,http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014. 00457.

FitzGerald,T.H.,Dolan,R.J.,Friston,K.,2015a.Dopamine,rewardlearning,and activeinference.Front.Comput.Neurosci.9,136.

FitzGerald,T.H.,Schwartenbeck,P.,Moutoussis,M.,Dolan,R.J.,Friston,K.,2015b. Activeinference,evidenceaccumulation,andtheurntask.NeuralComput.27 (2),306–328.

Frank,M.J.,Scheres,A.,Sherman,S.J.,2007.Understandingdecision-making deficitsinneurologicalconditions:insightsfrommodelsofnaturalaction selection.Philos.Trans.R.Soc.Lond.BBiol.Sci.362(1485),1641–1654. Friston,K.,Buzsaki,G.,2016.Thefunctionalanatomyoftime:whatandwhenin

thebrain.TrendsCogn.Sci.20(July7),500–511.

Friston,K.,Adams,R.,Montague,R.,2012a.Whatisvalue—accumulatedrewardor evidence?Front.Neurorob.6,11.

Friston,K.,Adams,R.A.,Perrinet,L.,Breakspear,M.,2012b.Perceptionsas hypotheses:saccadesasexperiments.Front.Psychol.3,151.

Friston,K.,Schwartenbeck,P.,FitzGerald,T.,Moutoussis,M.,Behrens,T.,Raymond, R.J.,Dolan,J.,2013.Theanatomyofchoice:activeinferenceandagency.Front. Hum.Neurosci.7,598.