Completeness and Complexity of Information Available to Parents From

Newborn-Screening Programs

Kathryn E. Fant, MPH; Sarah J. Clark, MPH; and Alex R. Kemper, MD, MPH, MS

ABSTRACT. Background. In 2000, the American Acad-emy of Pediatrics (AAP) Task Force on Newborn Screen-ing published a blueprint for the future of newborn screening that included recommendations for informa-tion provided to parents about screening.

Objectives. To evaluate the completeness of educa-tional material provided by newborn-screening pro-grams and to measure the reading level and complexity of the material.

Methods. Telephone survey of newborn-screening programs (nⴝ 51) followed by content analysis of edu-cational material.

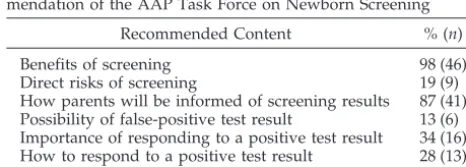

Results. All 51 programs responded (response rate: 100%); 47 of these programs made educational material available. None of the material included all elements recommended in the blueprint. Benefits of screening (98%) and how parents would be notified of results (87%) were included more often than the risks of screening (19%), possibility of a false-positive result (13%), impor-tance of (34%) and how to respond to (28%) a positive result, and the storage and use of residual samples (11%). The median readability grade level was 10. Grade-level complexity of the material was not associated with com-pleteness according to the AAP criteria.

Conclusions. Parent educational materials for new-born-screening programs do not meet the standard rec-ommended by the AAP, and there are important varia-tions between programs in the information provided to parents. Continuing research is needed to measure progress toward the goals outlined within the blueprint and to assess how these changes impact the care provided through newborn-screening programs. Pediatrics 2005; 115:1268–1272; health information, newborn screening, practice guidelines.

ABBREVIATION. AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics.

N

ewborn screening has led to dramatic reduc-tions in morbidity and mortality for a broad range of rare conditions through early detec-tion and treatment. There is currently no federally mandated minimum set of conditions for inclusion in newborn-screening panels, and the operations of andresources for newborn-screening programs are deter-mined at the state level. This results in wide varia-tions in newborn-screening programs, such as how parents and physicians are informed about newborn-screening results and the methods and resources available for follow-up and treatment for children with abnormal screens.1

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Task Force on Newborn Screening published a “blueprint” for the future of newborn screening to address concerns about variability among the new-born-screening programs and to develop a strategy to resolve ongoing and emerging challenges.2 This comprehensive report identified several key factors for successful screening programs. Some of these factors, such as expansion of public health infrastruc-ture, establishing advisory committees, and imple-menting program surveillance and research, will take time to develop. Other factors, such as provid-ing parents with comprehensive educational mate-rial about newborn screening, could be accomplished sooner through modification of existing materials.3

The AAP blueprint listed 7 recommendations for what should be presented in parent educational ma-terial: (1) the benefits of screening; (2) the potential risks of the screening test; (3) how parents will be informed of screening results; (4) the possibility of a false-positive test result; (5) the importance of re-sponding to a positive test result; (6) how to respond to a positive test result; and (7) the screening pro-gram’s policy for sample storage and use of stored samples. In addition, the task force stated the impor-tance of ensuring that the material is written at an appropriate literacy level.

We are unaware of any previous study that has focused on the content and complexity of educa-tional material produced by screening programs for parents. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the completeness of educational material provided by newborn-screening programs according to expert panel recommendations and to measure the reading level and complexity of the material.

METHODS Collection of Educational Material

In January 2004, the coordinators of each US newborn-screen-ing program (n⫽51) were contacted by telephone and asked to provide any standardized program materials used for educating new or expectant parents about newborn screening. We limited data collection to materials written in English and focused on the newborn-screening program; we excluded material on particular diseases only (eg, brochure on phenylketonuria). This study was From the Child Health Evaluation and Research Unit, Division of General

Pediatrics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Accepted for publication Sep 3, 2004.

doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0834 No conflict of interest declared.

Address correspondence to Alex R. Kemper, MD, MPH, MS, Child Health Evaluation and Research Unit, Division of General Pediatrics, University of Michigan, 6E08 300 N Ingalls Building, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0456. E-mail: kempera@med.umich.edu

approved by the University of Michigan Medical School Institu-tional Review Board.

Content Abstraction

A standardized data-collection instrument for content evalua-tion was developed and pilot tested for ease of use. Each pro-gram’s educational materials were evaluated to determine if they included full, partial, or no coverage of information related to the 7 components recommended by the AAP Task Force on Newborn Screening (benefits of screening, potential risks, how parents will be informed of results, the possibility of a false-positive result, the importance of responding to a positive result, how to respond to a positive test result, and the screening program’s policy for sample storage and use). For the risks associated with screening, we looked for statements regarding the direct risk of screening (eg, pain) and considered the harm of false-positive results separately along with statements about the possibility of false-positive re-sults. In this evaluation we also considered factors recommended for inclusion by other expert panels: descriptions of all conditions being screened, the likelihood of the conditions occurring, and the process and implications of screening refusal.4–6The presence of

information regarding costs associated with screening was also considered, because the majority of programs charge a fee for newborn-screening tests.1During the abstraction process,

repre-sentative quotations were recorded to illustrate the quantitative findings. One investigator (K.E.F.) abstracted all data. To ensure reliability of the data abstraction, a 10% sample of the material was independently abstracted by another investigator (A.R.K.). Inter-rater reliability was assessed with thestatistic.

Literacy Evaluation

Readability of the material was measured by using the SMOG grade formula, a previously validated measure of the complexity of patient-education material.7The formula involves tallying all

words withⱖ3 syllables in 30 selected sentences (3 groups of 10 consecutive sentences from the beginning, middle, and end of the document). Then, the square root of that total is obtained and its integer calculated. Finally, the number 3 is added to the integer to obtain the grade level of the document. Length and format of the educational material (eg, single-page, bifold, or trifold brochure, booklet), a secondary measure of material complexity, was noted for each program’s materials.

Data Analysis

Univariate and selected bivariate frequencies were used to summarize the findings. In addition to frequency counts for each component included in the study, we also calculated the total number of the 7 AAP Task Force on Newborn Screening recom-mendations included in the materials. Readability grade level was categorized intoⱕ9th, 10th to 11th, andⱖ12th grade. The2test

statistic was used to measure the strength of association in the bivariate analyses;P⬍.05 was considered statistically significant. Stata 8.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) was used for all statis-tical analyses.

RESULTS Availability of Educational Material

We contacted all 51 newborn-screening coordina-tors (response rate: 100%). All but 1 program re-ported that standardized educational material is available for parents about newborn screening (98%). However, 3 of the programs did not make the mate-rial available because they were in the process of revising or printing their materials. Thus, subsequent results are based on the materials available from 47 newborn-screening programs. There was high inter-rater reliability (⫽ 0.94) in the coding for the 10% subsample of reabstracted materials.

Material Inclusion of AAP-Recommended Items None of the program materials contain⬎5 of the 7 elements recommended by the AAP. Overall, 5

ma-terials (11%) have 5 items, 22 (47%) have 3 or 4 items, and 20 (42%) have ⱕ2 of the elements (Table 1). Additional detail regarding each AAP-recom-mended item follows.

Benefits of Screening

Nearly all program materials (n ⫽ 46) contain a statement about the benefit of screening, and we found very little variation in the content of these messages. Materials primarily cite the benefit of early detection and treatment (eg, “If identified early with newborn screening testing, some of these disorders can be treated before they cause serious health prob-lems”).

Direct Risks of Screening

Only 9 programs (19%) discuss the direct risks associated with screening. Of those, 5 present the risk of pain or infection. The other 4 materials cover risks of screening by stating that there is no significant risk to the infant. For example, 1 parent brochure states: “It makes a lot of sense to have the test done because there are no side effects and it’s perfectly safe.”

How Parents Will Be Informed of Screening Results

Materials from 41 programs (87%) communicate how parents would be notified, but there was varia-tion in the emphasis on parental responsibility. Of the 41 programs, 15 mention that parents would be notified if there were a problem but encourage fam-ilies to ask their child’s physician about the results. A similar number (n ⫽ 14) let parents know that they would be notified only if a problem was suspected, whereas 10 advise parents to ask their child’s health care provider for results. Only 2 state that families would be notified regardless of the result.

Possibility and Potential Harm of False-Positive Result

Only 6 of the materials (13%) explicitly mention that false-positive results are possible (eg, “The screening tests are very sensitive so truly affected infants will not be missed, and thus some nonaf-fected infants will have falsely positive results”). In addition, only 3 mention any risks associated with false-positive results (eg, stress, inconvenience).

Although not specifically mentioning false-posi-tive results, 33 materials (70%) address the potential need for retesting or the associated uncertainty about results. Materials discuss the need for retesting by offering reasons why an additional sample might be requested (n⫽ 17), such as the initial sample being collected too early or containing an inadequate

TABLE 1. Proportion of Educational Materials Provided by Newborn-Screening Programs (n⫽47) That Meet Each Recom-mendation of the AAP Task Force on Newborn Screening

Recommended Content % (n)

Benefits of screening 98 (46)

Direct risks of screening 19 (9)

How parents will be informed of screening results 87 (41) Possibility of false-positive test result 13 (6) Importance of responding to a positive test result 34 (16) How to respond to a positive test result 28 (13)

amount of blood for testing. A similar number of materials (n ⫽ 16) address parental uncertainty by stating that the need for retesting “does not neces-sarily mean that your infant has one of the condi-tions.”

Importance of Responding to a Positive Test Result

Materials from 16 programs (34%) provide a spe-cific reason (eg, “timely treatment if a problem is detected”) regarding the importance of following up after an abnormal result. However, 29 programs (62%) do not provide a rationale but simply state that responding quickly is important.

How to Respond to a Positive Test Result

Materials from 34 programs (72%) do not tell par-ents what they should do in the event of an abnormal test result. However, 13 of them (28%) contain spe-cific information (eg, “If you are asked to have your infant retested, please bring your infant back to the birth facility or your infant’s doctor as soon as pos-sible”).

Storage and Use of Stored Samples

Information regarding the policies for storage and use of residual samples are mentioned in the mate-rials from 5 programs. Most of them mention that samples are stored securely (n ⫽ 3); the length of time programs store specimens ranged from 90 days to 21.5 years. Materials state that stored samples may be used for research (n⫽3) or are not used for any other purpose (n ⫽ 2) without the request or prior written consent of parents.

Other Recommended Content

Description of the Conditions on the Screening Panel

All but 1 of the materials provide information about the conditions detected with the newborn-screening test; 9 materials (19%) provide a list or examples of conditions, whereas 37 (79%) offer a full description of each condition. In describing each con-dition, materials typically present details about prev-alence, disease course, and treatment.

Likelihood of Having the Conditions

Materials from 22 programs (47%) present preva-lence data to communicate the specific risk of each disorder. A qualitative statement (eg, “rare”) about the risk of the various conditions on the screening panel is presented in 13 materials (28%). There is no quantitative or qualitative information on the risk of the conditions in 12 of the materials (25%).

All of the materials (n ⫽ 47) discuss outcomes if the conditions are not treated. Of these, 8 provide a general statement (“mental retardation, growth fail-ure and even death”). The others present outcomes specific for individual conditions. Similarly, nearly all (n ⫽ 43) discuss the types of treatments, either generally (“special diets and medicines”) or specific to individual conditions (“treatment with biotin sup-plementation”).

Process for Refusing Newborn Screening

Of the 47 programs that submitted materials for analysis, 5 do not permit refusal of screening for any reason and therefore were excluded from this anal-ysis. Among states that permit refusal of newborn screening, 23 materials (55%) mention a parent’s right to refuse screening. Among those that include the option of refusing, few (n ⫽ 6) also discuss the implications of doing so (eg, “Your hospital, doctor and the clinic staff are not responsible if your infant develops problems from these disorders”).

Cost of Screening

Only 11 materials (23%) mention the costs associ-ated with screening. Of those, 2 indicate that testing is free, 4 mention that there is a charge for testing but do not specify the amount, 3 specify the cost of screening (ranging from $47 to $54), and 2 do not mention whether there are costs associated with the required screening tests but indicate that there is no extra cost for expanded or optional newborn-screen-ing tests. In addition, approximately half of the ma-terials (n⫽6) that mention costs indicate that the fees are typically covered by third-party payers, and 4 of the materials provide information about who to con-tact if an individual has no insurance and is unable to pay. The potential for incurring other ancillary charges associated with newborn screening (eg, “Your health care provider may charge a fee to col-lect the specimen”) is mentioned by 2 of the program materials.

Complexity Evaluation

The median SMOG readability grade level of ma-terials was 10. Overall, 12 of the mama-terials (25%) were written at the 7th- to 9th-grade level, 28 (60%) were written at the 10th- to 11th-grade level, and 7 (15%) were written at theⱖ12th-grade level. Materials that describe all conditions on the screening panel (n ⫽

37) were more likely to be of greater complexity compared with those that only list conditions or give examples (n ⫽ 9) of conditions (P⫽ .03). For mate-rials that list conditions, 67% were written at the 7th-to 9th-grade level, and 22% were at the 10th- 7th-to 11th-grade level. For materials with a full description of conditions, 16% were written at the 7th- to 9th-grade, and 68% were at the 10th- to 11th-grade level. Materials from 27 programs (58%) present new-born-screening information in a bifold or trifold for-mat; 18 (38%) use a larger booklet, and 2 (4%) present the information in a single page. Document size was not associated with readability scores (P⫽ .12).

The complexity of the material, measured as either readability or size, was not associated with complete-ness according to the AAP criteria (P⫽ .12 and .98, respectively).

DISCUSSION

materials highlight the benefits of screening and compulsory nature of testing in similar ways.

Although most materials present information on how parents will be informed about the results of screening, we found important differences in the expected role of parents in learning these results, ranging from families being notified regardless of the result to parental inquiry being emphasized. Some of these differences likely arise from programmatic dif-ferences.8

Only 13 of the programs informed parents about what steps should be taken in the event of a positive screening result. Typically, this was limited to a de-scription of the need for retesting. Because programs make a concerted effort to quickly identify and track children with positive results and because the child’s primary care physician is often responsible for noti-fying parents of the result, it could be argued that informing parents about the necessary steps after a positive test in the educational material provided at the time of screening is unnecessary. However, pro-viding this information might decrease parental anx-iety by emphasizing that an abnormal screen does not confirm disease and might enhance timely low-up by underscoring the need for quick fol-low-up testing.

Most materials were written at the ⱖ10th-grade level. According to the National Adult Literacy Sur-vey, almost half of adults in the United States have limited or extremely limited reading skills, and other studies demonstrate that more than one third of En-glish-speaking patients have difficulty reading at the 10th-grade level.9–11 Additionally, the National Work Group on Literacy and Health recommends that material be written at or below the sixth-grade level to increase the likelihood that patient-education materials be read and understood.12 Providing par-ents with comprehensive educational material about newborn screening at a lower reading grade level might be challenging; however, among the material we reviewed, those that were more complete (ie, covered more of the AAP-recommended elements) did not have a higher reading level than those that were less complete.

As long as newborn-screening programs are man-aged at the state level, program variations will per-sist. The impact of the variations in the information provided by these programs is unclear; the associa-tion between messages in educaassocia-tional materials and compliance with retesting or parental anxiety over false-positive results has not been explored. In addi-tion, we are unaware of any studies that have as-sessed what information parents need about new-born screening and how to provide this education most effectively. Similarly, no studies have ad-dressed other sources of screening information for parents, such as conversations with health care pro-viders.

Our study did not examine the context in which these written materials are presented to parents. A survey found that newborn-screening programs typically do not provide educational materials di-rectly to parents but rather distribute them to hos-pitals and primary care providers, who are

ex-pected to share them with parents.1 Although there have been efforts to encourage information sharing with parents during the prenatal period, much of the responsibility for educating parents falls to individual hospitals and birthing centers after delivery. The postpartum period is a chal-lenging time for new parents, and it is unclear how much information they can retain. Therefore, the Task Force on Newborn Screening recommended that prospective parents receive information about newborn screening during the prenatal period, preferably during a routine third-trimester prena-tal care visit.2 A survey in 2000 found that some newborn-screening programs (13 of 51) had poli-cies to encourage or require parent notification about newborn screening during the prenatal pe-riod.8Despite evidence that policies regarding the timing of parental education exist, work is still needed to document if and when parents actually receive newborn-screening materials.

Our study focused on the written material pre-sented to parents on newborn screening. There-fore, elements lacking in the written materials may be presented verbally to parents during encounters with prenatal and pediatric care providers. Addi-tional work should be done to assess provider knowledge of newborn-screening programs and current patient-education practices. By ensuring provider coverage of these issues or updating pro-gram materials to include all AAP Task Force on Newborn Screening–recommended elements, par-ents can be provided with the information needed to understand the purpose of newborn screening and the meaning and implications of a positive result.

Parent education represents only one component of the AAP Task Force on Newborn Screening blue-print; the failure of educational material to meet the blueprint recommendations does not necessarily im-ply that there has not been important programmatic change to address other issues. This study, however, emphasizes the need to measure progress toward the goals outlined within the blueprint and to assess how these changes impact the care provided through newborn-screening programs.

REFERENCES

1. United States General Accounting Office.Newborn Screening: Character-istics of State Programs. Report No. GAO-03-449. Washington, DC; 2003. Available at: www.gao.gov/new.items/d03449.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2004

2. Task Force on Newborn Screening. Serving the family from birth to the medical home. A report from the Newborn Screening Task Force con-vened in Washington DC, May 10 –11, 1999.Pediatrics.2000;106(2 pt 2):383– 427

3. Hiller EH, Landenburger G, Natowicz MR. Public participation in med-ical policy-making and the status of consumer autonomy: the example of newborn-screening programs in the United States.Am J Public Health.

1997;87:1280 –1288

4. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research.Screening and Counseling for Genetic Conditions: The Ethical, Social, and Legal Implications of Genetic Screening, Counseling, and Educational Programs. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1983

report of the Task Force on Genetic Testing. 1997. Available at: www.genome.gov/10001733. Accessed April 19, 2004

6. US National Research Council Committee for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism. Genetic Screening: Programs, Principles, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1975

7. McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading: a new readability formula.J Reading.

1969;12:639 – 646

8. Kim S, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Tonniges TF. Examination of the com-munication practices between state newborn screening programs and the medical home. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/111/2/e120

9. Kirsch IS, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Findings of the National Adult Literacy

Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2002. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93275.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2004

10. Gazmararian JA, Baker DW, Williams MV, et al. Health literacy among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization.JAMA.1999;281: 545–551

11. Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR. Relationship of func-tional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease. A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes.Arch Intern Med.

1998;158:166 –172

12. Communicating with patients who have limited literacy skills. Report of the National Work Group on Literacy and Health.J Fam Pract.

1998;46:168 –176

A VERY DIFFERENT VIEW OF ADHD FROM ENGLAND!

“A large swath of Britain’s youth now appears to be in the grip of ADHD, with an estimated 6 to 8 percent of our children suffering from this distressing ailment. Psychiatrists have long been aware of the problems of the ill-disciplined, overactive child; as long ago as 1865 the German physician Heinrich Hoffman wrote of a boy he called ’fidgety Philip’ who ’won’t sit still, wriggles, giggles, swings backwards and forwards, tilts up his chair’ and would probably grow up to be ’rude and wild.’ But it was only in 1987 that the label of Attention Deficit Disorder—later length-ened to include hyperactivity—was officially attached to such behavior. First used in the USA, it soon became fashionable in England. Predictably, once the condition had been created, huge numbers of children were soon found to be its victims. . . . In official circles, including the Department of Health, the existence of ADHD as a physical medical condition is now accepted as a fact. . . . And so the way is opened to a cornucopia of taxpayer-funded benefits. The family with an ADHD child can claim a weekly Disability Living Allowance, worth a maximum of £99.85, plus a carer’s allowance of up to £44.35 per week, and the disabled child tax credit, now standing at £2,285 per year. If the family is on income support—and, inevitably, many ADHD children are brought up in jobless households—the parents can also claim a disability premium worth up to £42.49 per week, plus a carer’s entitlement of £25.55 a week, a reduction of 50 percent in the TV license fee, and grants from the social fund which can help with basic household goods. This is the madhouse of modern Britain, where families of badly behaved children are rewarded by the state with an increase in welfare benefits.”

McKinstry L.The Spectator.February 26, 2005

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-0834

2005;115;1268

Pediatrics

Kathryn E. Fant, Sarah J. Clark and Alex R. Kemper

Newborn-Screening Programs

Completeness and Complexity of Information Available to Parents From

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/5/1268

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/5/1268#BIBL

This article cites 6 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/fetus:newborn_infant_

Fetus/Newborn Infant

_management_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/administration:practice

Administration/Practice Management

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-0834

2005;115;1268

Pediatrics

Kathryn E. Fant, Sarah J. Clark and Alex R. Kemper

Newborn-Screening Programs

Completeness and Complexity of Information Available to Parents From

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/5/1268

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.