CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 General background

Fleet management has become a major focus of management over the past number of years. This is evident from the following quote from GE Capital Fleet Services: “The fleet sector is a difficult, complex and dynamic market place with many issues to be addressed…. There are few organisations that are not seeking to undertake their roles more efficiently, to run the business more smartly, and to cut the cost of the organisation. Those cuts may come from doing things smarter, from buying or selling more cost-effectively or through controlling costs more efficiently. The requirement of management is to cut cost levels while boosting revenues…. and getting even greater value from the company car could help that task” (GE, 2000:1)

GE Capital Fleet Services (GE) further estimates that between 70% and 73% of new cars sold in the United Kingdom are apparently used for and financed by business in some form or another. There are a number of ways in which such vehicles could be provided. Some vehicles are owned by the business and used by employees, others are provided to employees through soft loans or through kilometre allowances (GE, 2000:5). Each of these has cost and value implications to both the organisation and the individual.

From the organisation’s point of view, the range of pressures on vehicle fleet management is both diverse and intense. There is a demand to cut the overall cost of doing business, including fleet costs, yet corporate image has to be protected. The vehicle is often the businesses’ only tangible asset a customer will see during a year. Elsewhere, the organisation has to be careful that its car provision policy does not move out of line with competition, or there will be a risk of loosing key employees to a better package. Shareholder value (or

value to the taxpayer in the case of government) and the realistic provision of “perks” is often an issue (GE 2000:5).

From the individual’s side, the issues are often more emotional. On the one hand, they seek larger and better vehicles but at the same time do not necessarily wish to pay the increased tax bill. Other pressures include ego, status, security, lifestyle etc. According to GE, employees have demanded and have been granted a wider choice of vehicles, a fact that has real implications as regards the total cost incurred by the organisation. “Choice of car”, as well as the extent of the allowance, is often raised at appointment interviews (GE, 2000:6).

In the same way that businesses depend on vehicle fleets to conduc t their business, the South African government also depends on vehicle fleets to conduct its business. These tasks are related to government functions such as attending and arranging meetings and workshops, traffic law enforcement, health care, education, service vehicles, inspection services, etc. Government, being accountable to taxpayers as well as to its employees, has to deal with many similar complexities and problems as are experienced by the business sector.

There has been a trend in South Africa to outsource the ownership and risk of statutory vehicle fleets (see Section 8.3). Similar trends are not necessarily followed overseas. According to Tolley (Tolley/dial review, 1996-97, as quoted by GE, undated: 27) most vehicles in larger fleets in the United Kingdom (i.e. fleets of more than 500 vehicles) are wholly owned by those companies. Also refer to Section 8.2 in this regard.

In business, many fleet vehicles today belong to individuals through company car schemes, allowance schemes etc. (GE, undated). This lessens the need to manage large numbers of vehicles that are owned by such businesses. In government, a significant number of vehicles are also allocated to individuals within a car allowance scheme. These schemes apply mostly to officials in

higher income categories and to those who regularly travel long distances for work purposes (National State Tender Board, 2001).

1.2 Government motor transport in South Africa

According to the Department of Public Service Administration, the South African public service comprised 1 065 999 people at the end of 1999. (Department of Public Service Administration, 2000: Chapter 3). These employees (which exclude parastatals such as Telkom and Escom) are all potential users of government motor transport. They have an obligation to provide services to the public and other institutions they serve, regardless of the income and driving patterns of individual employees (see end of Section 1.1). For this reason the Government owns and operates a substantial fleet of motor vehicles. These vehicles have traditionally been supplied to government departments and their employees through government garages. Government garages are found in all nine provinces with the largest being in Gauteng (Wesbank, undated b).

The management of government motor transport in South Africa is decentralised to the nine provinces. Each of the provinces is autonomous – they have the right to decide on their own government motor transport policies and procedures, within national laws. The National Department of Transport plays a co-ordinating role between provinces. The National Department of Transport, for instance, issues tenders for various national contracts to source vehicles and services, in which most of the nine provinces take part simultaneously. These contracts are mainly for the supply, administration and maintenance of government vehicles. At present the total fleet managed by the government garages of all nine provinces consists of approximately 29 000 vehicles (Wesbank, undated b).

The Gaute ng province represents the largest user of government motor transport vehicles. The province generates more than 36% of the country’s gross national product and, even more impressively, more than 25% of the

gross national product of all countries in southern Africa (Gautrans, 2001). Gauteng is also the home of a large number of state departments (mostly in Pretoria) and is often seen as the leading province in South Africa. For these reasons it was decided to focus the study of government motor transport on the Gauteng province.

1.3 Description of government motor transport in Gauteng

According to the Department of Public Service Administration, 111 495 people were working for the Gauteng Provincial Government at the end of March 1999 (Department of Public Service Administration, 2000: Chapter 3). These employees are based in government buildings, schools, hospitals, prisons etc. throughout the province, and in order to render an efficient public service, these employees need reliable and cost-effective transport. This transport is partly supplied to employees through subsidised vehicles (outside the field of study), as well as through the Government Garage – the focus of the study.

In 2000 the Gauteng Government Garage (referred to as "Government Garage" in this study) was serving 12 user departments in the Gauteng province (Gauteng Provincial Government, 22 November 2000). Gauteng is however also host to a large number of national departments and commissions, many of which have to be served by the Government Garage from time to time. These national departments and commissions are also termed "user departments" in this study. Although the total number of user departments changes from time to time, the average of 40 user departments and 400 user sites (both national and provincial) was generally accepted at the time of this study (Gautrans, 14 July 2000; Gautrans, 19 September 2001 and others). The term "user site" or "site" refers to the office from where a transport officer issues vehicles to drivers.

The Gauteng province operates on a centralised vehicle asset model. All vehicles are centrally owned by the Government Garage, which has two operational branches – one in Pretoria and one in Johannesburg. It owns

about 6 000 vehicles (Gautrans, 19 September 2001). Approximately 80% of these vehicles are on long-term rentals to user departments on the basis of a full maintenance rental from the Government Garage. The other 20% are short-term rentals, split between a hire pool, where the user department supplies its own driver, and a taxi service, where the Government Garage supplies the drivers (Robbie, April 2002). Dividing 6 000 vehicles by 400 user sites in Gauteng gives an average of 15 vehicles per site.

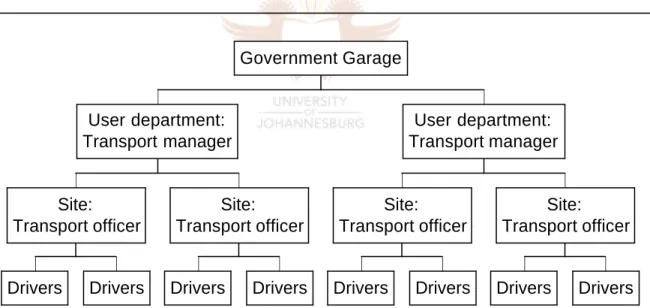

Each user department has a transport manager who is responsible for the management of the user department's fleet. Depending on the size of the department, the transport manager may or may not have a transport officer on each site who reports to him. If not, the transport manager fulfils both roles and is the contact person for the Government Garage.

Figure 1.1 depicts the transport utilisation structure diagrammatically.

Drivers Drivers Site:

Transport officer

Drivers Drivers Site:

Transport officer User department:

Transport manager

Drivers Drivers Site:

Transport officer

Drivers Drivers Site:

Transport officer User department:

Transport manager Government Garage

Figure 1.1 Transport utilisation structure in Gauteng Provincial Government (Gautrans, 14 July 2000)

User departments pay a predetermined monthly rate to the Government Garage for the use of each vehicle. The Government Garage is responsible for costs such as maintenance, accident costs, cost of theft and vehicle

replacement. In the financial year ending March 2001, the total income of the Gauteng Government Garage was approximately R 225 million (Gauteng Provincial Government, 15 May 2001). This amount is indicative only, as the provincial government was working on a cash flow basis and transactions such as transfers between financial years may skew the picture.

In order to utilise government motor transport, an employee submits a request for transport to the transport officer at his site. Should permanently allocated vehicles be available, the officer issues the required vehicle from the vehicle pool. Should a vehicle not be available, he requests a vehicle from the Government Garage’s hire pool. These vehicles are then issued to the user department on a short-term basis. The transport officer and the driver are collectively responsible for the return of the vehicle.

1.4 Developments relating to government motor transport in

South Africa

From the previous paragraphs it is evident that government motor transport is a major service and support function of government to its employees. In its endeavour to explore higher efficiencies in fleet management, the Gauteng government has over the last number of years taken a number of initiatives regarding the management of its vehicles. This was initiated amongst others by a decision during October 1996 by the nine Provincial Members of Executive Councils (MECs) for Transport and the National Minister of Transport, that each province should undertake an investigation into the provision of government motor transport. This decision was taken in the light of operational losses suffered by the government garages, inadequate management control and operational systems, as well as difficulties in obtaining correct information from user departments. Other reasons for the decision were ageing fleets that resulted in increased operational costs, the tendency amongst user departments to use external suppliers and high levels of fraud and abuse (Deloitte, 1997:1). The above decision was followed by a viewpoint of the National Department of Transport that government motor

transport had to be outsourced for "efficiency and savings" (National Department of Transport, 1999: 14).

In line with all the above, an investigation was launched in Gauteng, through a reputable management consulting company, which investigated the various components within the Gauteng Government Garage (Deloitte, 1997). The outcome of this investigation led to a decision by the Gauteng Provincial Legislator (or Cabinet) on 1 April 1998 that concluded the following:

•

To outsource the provision of the VIP chauffeur driver services, short-term hire vehicle services and maintenance and repair services.•

To implement a daily tariff (in addition to the existing kilometre-tariff), in order to improve the utilisation and cost recovery of the vehicles.•

That responsibility, accountability and control of vehicles eventually be permanently “decentralised” to the user departments (Draft minutes of Gauteng Provincial Cabinet meeting held on 1 April 1998: Item 8.2.4).Following this decision, a number of developments occurred that contributed to a rethink of the original proposals to outsource and decentralise the Government Garage fleet functions. Two of these were the following:

•

A national pilot project regarding the outsourcing of the supply of vehicles to four user departments commenced in 1999 (National Department of Transport, 1999)1. The apparent costs of these services

1

Because of the perceived problems in government motor transport, total outsourcing of services was seen as an option. The National Department of Transport decided to test this option by contracting the supply of government motor vehicles to 4 national departments to a private service provider (National Department of Transport, 1999).

were approximately twice the costs of the equivalent services provided by the Government Garage (Future-U & VSA, 1999: Appendix G).

•

KwaZulu-Natal decentralised its fleet management and control functions to its user departments (KwaZulu-Natal Department of Finance 1999).In the process of implementing the April 1998 decision, certain practical considerations, such as labour implications also became apparent in Gauteng. These developments led to a shift in emphasis, where other considerations such as labour, costs and inter-dependency of services were also considered.

In January 1999, the following proposal was approved to improve gove rnment motor transport in Gauteng (Gautrans, January 1999):

•

A three-year period would be allowed to establish the most cost-effective way of executing the April 1998 Gauteng Cabinet decision.•

Cost implications, labour implications and lessons learnt from other institutions would form important inputs into the final decision about the way forward.In 2000 the situation in the Gauteng Government Garage was once again revisited. At that time, daily tariffs had been implemented and better vehicle running cost statistics became available from the supplier of the fuel card system that provides running cost information of Government Garage vehicles in the province (National Department of Transport, 1998: Contract RT 46 S P).

The costs of the insourced versus outsourced transport options were compared. These analyses revealed the following (Gautrans, January 2001):

•

The costs of providing hire pool and taxi services internally were significantly lower than known private sector options such as the National Outsourced Pilot Project referred to above.•

The overhead costs of permanently allocated vehicles in Gauteng (centralised – with trading account) were significantly lower than those in KwaZulu-Natal (decentralised – user departments pay direct costs). There were also insignificant differences in running costs per kilometre between the two provinces.The 1998 Cabinet decision to outsource all ad hoc hire vehicles and to decentralise permanently allocated vehicles to user departments was subsequently reviewed through a new proposal to transform the Government Garage into a cost-effective customer-orientated entity, fulfilling and/or facilitating the services mentioned earlier (Gautrans, January 2001).

The proposal also stated that, with regard to the maintenance function, Government had an obligation to control its vehicle assets. A workshop control team would therefore remain in place. At the time of the proposal, the Government Garage employed about 16 artisans fulfilling various control functions (Future-U & VSA, 1999: Annexure F). Any supplementary staff would be retrained and redeployed for basic services such as vehicle cleaning and tyre fitment. The objective was that these teams might eventually evolve into independent small enterprises.

In order to improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of provincial transport, the latter proposal made provision for an improved personnel organisation structure, improved user education and an improved management information system. This new approach represented a major departure in thinking from the original decision to outsource the hire pool, taxi and maintenance services and to decentralise the permanently allocated fleet to user departments.

From the foregoing information it is evident that some decisions were taken regarding fleet management in the Gauteng province that appear to be contradicting each other. The question may be posed why these apparently contrasting decisions were taken and on what information they were based. From the sequence of events it becomes evident that, as more information became available, decisions were reviewed. The decisions were also based on a more outward looking focus. This can be illustrated as follows:

•

As a result of the lack of an all-inclusive integrated fleet information system, the Gauteng Cabinet had to base its decision on the limited financial information at its disposal (Deloitte, 1997).•

By mainly focusing inward on the Government Garage, e.g. on the financial matters regarding fleet management within the Government Garage (Deloitte, 1997), potential external impacts and influences as well as the inter-dependency of services may have been overlooked. These influences include the interests of various stakeholders, such as the taxpayer, staff, user departments and Government, which is represented by its political leaders (refer to Chapter 7). Taking account of these external impacts may lead to more broadly based decisions, which may differ from those that are mainly based on internal factors.To conclude, government motor transport in South Africa is in a state of flux. Uncertainty exists as to the best way forward. Widely different decisions are being made regarding the management of government motor transport in South Africa. Some provinces are outsourcing their fleets, whilst others are decentralising their fleets to user departments. In some cases there is a movement from a decentralised to a centralised system (refer to Section 8.3).

There is a need for clarity on how to arrive at decisions that will result in the long-term financial and operational sustainability of government motor transport, both within the Gauteng province as well as other provinces.

1.5 Motivation for the study

The current approach to fleet management in Gauteng is not an all-encompassing process, involving the interests of all the important stakeholders. Problems have to be solved without all-inclusive and focused management information that is needed to take informed decisions.

Contradicting signals from fleet management institutions within government throughout South Africa are causing uncertainty as to the way forward. There is a need for a decision-making process that takes into account the broader picture including the interest of all the important stakeholders. The lack of a clear, all-inclusive decision-making process results in uncertainty with regard to how to treat government motor transport in Gauteng. This gave rise to the reversal of decisions once the impacts became clear.

There is therefore a need to provide an overall strategic framework within which more informed decisions could be taken. This will reduce uncertainty and provide a solid base from where government motor transport could be managed and developed.

1.6 Objectives of the study

The objectives of the study are as follows:

•

To demonstrate the importance of a systems approach, which includes a structured problem-solving and decision-making process, towards the efficient management of government motor transport.•

To develop a structured value system that can form the basis for an efficient fleet information system.•

To apply the systems approach to develop a conceptual integrated fleet information system, based on the above value system, and to demonstrate how such an integrated fleet information system is essential for cost-effective fleet management in general and for fleet management in the Gauteng Provincial Government in particular.1.7 Focus and scope of the study

The focus of this study is government motor transport within the Gauteng Provincial Government. The study is limited to those vehicles under the direct control and ownership of the Gauteng Government Garage and which are used to undertake official business in the Gauteng Provincial Government. These include vehicles used by both provincial and national user departments, mainly within the Gauteng province. The study excludes vehicles that are also used by employees for private purposes and that are partly financed through monthly allowances.

Note: Unless implied otherwise by the context, the term Government Garage in this study refers to the Gauteng Government Garage, being the leading institution of government motor transport in Gauteng.

1.8 Methodology followed to undertake the study

The methodology followed to undertake the study was the following:

•

A literature research was undertaken. As part of this research, the systems management approach was researched with a view to apply the theory to government motor transport. This research included the latest articles and conference papers regarding fleet and systems management.•

Interviews were conducted with people involved in managing fleets inside and outside South Africa.•

Correspondence was conducted with institutions managing large fleets outside South Africa, specifically Austria and Germany.•

The International System Dynamics Conference of 2002 was attended in Palermo, Italy, where various papers on systems thinking and system dynamics were presented.•

A study tour to Germany was linked to the conference in Italy. The management of similar fleets was investigated, especially with a view to determine the extent to which systems management theory is applied to the management of these fleets.1.9 Layout of study

The layout of this study is as follows:

Chapter 1: Background, motivation, objectives, scope, methodology and layout of study.

Chapter 2: History and p hilosophy of the systems approach.

Chapter 3: Theoretical discussion of the systems process for later application in the study.

Chapter 4: A systems perspective on fleet management (i.e. in a broader context than the Government Garage).

Chapter 5: Government motor transport management in the Gauteng Provincial Government.

Chapter 6: Application of the systems management approach to fleet management in the Gauteng Provincial Government.

Chapter 7: Application of the systems approach to develop a conceptual integrated fleet information system for the Gauteng Provincial Government on the basis of a structured value system.

Chapter 8: Applicability of the systems approach to institutions managing large fleets inside and outside South Africa, and to outsourcing decisions.