JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WORK

& SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Volume 03, Number 01 & 02, 2012

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL WORK

VISVA-BHARATI

Journal of Social Work & Social Development (JSWSD)

JSWSD is a bi-annual refereed journal to publish original ideas that will promote issues pertinent to social justice, well being of individuals or groups or communities, and social policy as well as practice from development perspectives. It will encourage young researchers to contribute and well established academics to foster a pluralistic approach in the continuous efforts of social development.

Editor:

Asok Kumar Sarkar Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan

Editorial Advisors:

Surinder Jaswal Professor, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai B. T. Lawani Director, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune Sukladeb Kanango Retired Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Gora Chand Khan Retired Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan

Editorial Board:

P. R. Balgopal Professor Emeritus, University of Illinois, USA Sonaldi Desai Professor, University of Maryland, USA Niaz Ahmed Khan Professor, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh D. Rajasekhar Professor, ISEC (Centre of Excellence), Bangalore P. K. Ghosh Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Kumkum Bhattacharya Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Monohar Power Professor, Charles Stuart University, AU Rama V. Baru Professor, JNU, New Delhi

Swapan Garain Professor, TISS, Mumbai

© Copyright 2012 by Department of Social Work, Visva-Bharati

The material printed in this journal should not be reproduced without the written permission of the Editor. The statements and opinions contained within this publication are solely those of the contributors and not of the Editor or Department of Social Work, Visva-Bharati. For more information about subscription or publication, please contact: Prof Asok Kumar Sarkar,

Department of Social Work, Visva-Bharati,

Sriniketan-731236, Birbhum, W.B., India.

Editor’s Note

I am extremely sorry for late after releasing the last issue. The reasons for late include paucity of articles, poor quality of papers received and several pre-occupations in the Department. The present issue is a combined issue of June and December of 2012. It has incorporated eight papers which broadly cover philosophical issues, social development issues and health care issues. All these papers are research based and contributed by the university teachers. There is also a book review at the end. General ideas about contribution of the authors are mentioned below:

Mr. Parthasarathi Mondal is of the opinion, Indian thought is largely considered not as philosophy proper but as being concerned with something larger, something as profound and deep as life itself. The entire energy of thinking is perceived to be concentrated on the final goal of attaining enlightenment or freedom, of liberating the human spirit from its earthly bondage. In contradistinction with the more materialistic and theoretic West, the basic point of Indian philosophical reflection is considered to be the practical and experiential processes through which enlightenment and liberation are achieved. In his paper, he looks at some of the main lines of argument of the nationalist reading of Indian philosophy in its more orthodox moments before surveying some of the critiques of such a reading. It is hoped that such an endeavour would act as a stimulus for further Indian philosophizing in its own terms.

Dr. R. Venkata Ravi describes, there is a need for effective relationships among the government organizations and civil societies to implement development policies in a more responsive, sustainable and cost effective manner in rural areas. His paper establishes this argument through data base. It shows the Panchayats exhibit political willingness to development; the CBOs bring in the possible resources and ensure people's participation. The NGOs could help the villagers to plan for themselves and also bring possible resources to supplement the local resources for the development. The partnership helps each other to tackle their weakness and increase the combined strength among them to address collectively to develop the rural areas.

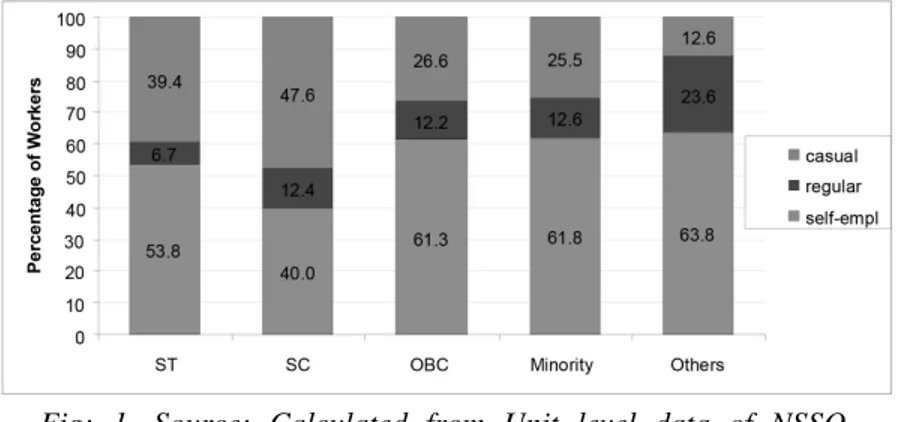

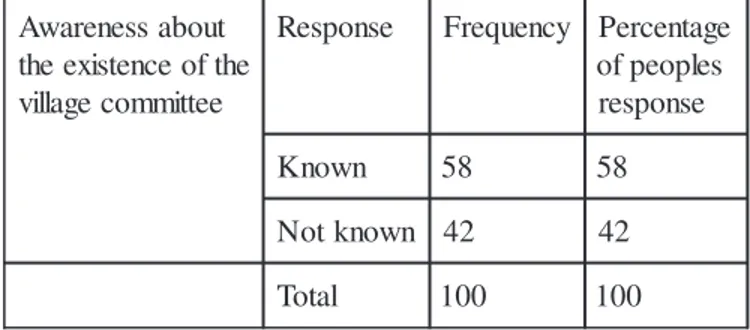

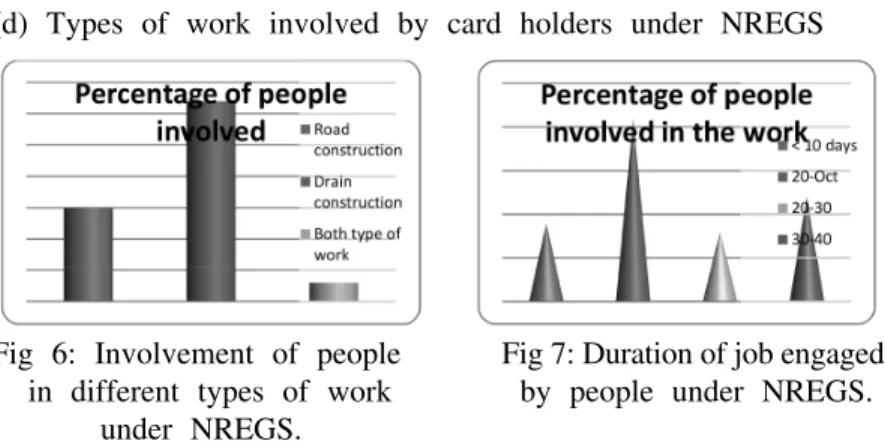

(SGSY) and Swarna Jayanti Shahari Rozgar Yojana (SJSRY) have been launched. These schemes aim to provide additional or seasonal employment and also to supplement the income of poor people. Her paper attempts to study and understand the implementation of NREGS and the role of the local village committee under NREGS. It further tries to explain the awareness level and the problems of village people who are availing the services of NREGS. The study is determined by 100 respondents who have job card holders of NREGS and key informants like Goan Panchayat members, village committee members of Hatitilla Community, Cachar District, Assam. Descriptive research design is used for the study and simple random sampling is chosen to select the respondents. Interview schedule and focused group discussions were used as tools of data collection. The study highlights the importance of evaluation and monitoring to curb the corruption at different levels and its impact on livelihood security.

Dr. Rakesh Dwivedi attempts to analyse, HIV/AIDS pandemic is a global problem affecting 34 million people worldwide. India also has a high prevalence. HIV/AIDS is a behavioral oriented problem which cannot be treated only by medicine; it also requires more psychological and social support. Restoration and promotion of health are the ultimate goals of health care interventions. It was realized that the health care interventions should focus on all the dimensions of health that are physical, mental, social and spiritual. Patient's satisfaction predicts about the treatment utilization and adherence. The study was conducted among 26 HIV positive persons having anti retroviral therapy (ART). The objectives of study were to determine the patient's satisfaction for quality of care and their quality of life.

Dr. Grace Laltlinzo and Mr. David Buhril highlights, the study of new social movements in the Northeast is the study of current developments by analyzing very recent new social movements. This imperative does not arise out of simple interest, but rather from the fact that we may well be about to enter one of the most exciting periods in the history of new social movements. In order to make our treatment more coherent, this paper discusses the aggressive dam building pursuit in the Northeast; focusing on two cases, out of the abundance, that validates the rise of new social movements. Moreover, the theoretical concepts of the new social movements are integrated to explain the "newness" of the new social movements in Northeast India. While saying that, it remains to be said that the study of new social movements is a recent mode of inquiry.

Mr. Indranil Sarkar and Professor Asok Kumar Sarkar's paper is an outcome of the study conducted in three villages (Kondorpopur, Taltor and Singi) of Birbhum District, West Bengal. The study focuses on the changes that the women of the SHGs have perceived in the context of their participation in the community, family decision making, and political affairs. The research had a qualitative approach. Purposive sampling was used to select the respondents keeping in mind certain criteria such as the respondent should have two to five years of SHG experience, should be between 25 to 30 years of age, and should be from deferent levels of the society. Twelve cases were studied in details and exploratory research design was adopted. The study found, though initial motivation of the respondent was monitory,the participation in the community increased after joining the SHG. But the political participation remained same because of political violence in the state. Huge range of changes were seen within the self perception, mobility within and outside the village increased for the women, respect from the family as well as from the community were more, and economically the women became independent which led ultimately to empowerment and the human development process.

to design the policies. Mrs Roy's paper tried to understand the development of the health insurance sector in India over time. The first two sections dealt with the pre independence and post independence health insurance scenario in India respectively. The third section presented the contemporary situation in the health insurance industry in India today. Finally there was a section that focused on the linkages that health insurance provision had with anti-oppressive practices.

The issue ends with a book review written by Miss Madhura Chakraborty. The book is on 'Adolescence Education' by Girish Bala Choudhary. It may be ironic and questionable how the review of the book published in 2014 can come in the volume of 2012. In this regard, please note that this issue is coming out after publication of that book. Last but not the least, I express my sincere thanks to all the contributors, reviewers and members of the editorial board for their intellectual support to continue this journal. Hope readers will find the issue informative and useful.

Asok Kumar Sarkar Editor

CONTENTS

______________________________________________________________

Editor’s Note

Philosophy and Nationalism in India: A Preliminary Essay 1

Parthasarathi Mondal

Grassroots Partnership for Rural Development:

A Study in Andhra Pradesh 34

R. Venkata Ravi

Understanding the Implementation of National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) : A Study

of Hatitilla Community in Cachar, Assam 65

M. Tineshowri Devi

Evaluation of Patient’s Satisfaction and Quality of Life among Patients Attending Specialized HIV/AIDS

Clinics in Lucknow 78

Rakesh Dwivedi

Psychiatric Social Work Services in Family Psychiatry

Unit - An Experience of NIMHANS 84

Renjith R. Pillai & R. Parthasarathy

Dams and the Rise of New Social Movements in

Northeast India 92

Grace Laltlinzo & David Buhril

Women’s Participation, Empowerment and Human Development: A Case Study of SHG Members

in Birbhum 114

Indranil Sarkar & Asok Kumar Sarkar

Development of Health Insurance in India: Examining

through the Lens of Anti-oppressive Perspective 145

Paramita Roy

Book Review 159

Philosophy and Nationalism in India: A

Preliminary Essay

Parthasarathi Mondal*

Abstract

In philosophical terms, Indian thought is largely considered not as philosophy proper but as being concerned with something larger, something as profound and deep as life itself. The entire energy of thinking is perceived to be concentrated on the final goal of attaining enlightenment or freedom, of liberating the human spirit from its earthly bondage. In contradistinction with the more materialistic and theoretic West, the basic point of Indian philosophical reflection is considered to be the practical and experiential processes through which enlightenment and liberation are achieved. In this paper we look at some of the main lines of argument of the nationalist reading of Indian philosophy in its more orthodox moments before surveying some of the critiques of such a reading. It is hoped that such an endeavour would act as a stimulus for further Indian philosophizing in its own terms.

Keywords: Indian philosophy, classical philosophy, modern Indian thought, nationalism

Introduction

Centuries of exertions by explorers, traders, colonialists and Indologists have exposed that vast tract of territory widely known as the Indian sub-continent, and its peoples, to economic, political, military and social influences from all over the world. This transaction has also given the West precious knowledge and familiarity with things Indian. The recent spate of liberalization and globalization has made this process all the more keen, urgent and insistent. Thankfully, therefore, much of India’s image as a land of snakes, maharajas

and naked fakirs has given way to one of a modernizing economy and society with all attendant vicissitudes of a fledging democracy, the largest in the world. Interestingly, however, attitudes towards social and philosophical life have been more resistant to change. India’s march towards modernity is perceived to be pulled back by

———————————

* Chaiperson, Centre for Social Theory, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, P.B.8313, Deonar, Mumbai, 400088, Email: pmondal@tiss.edu, mondalparthasarathi@hotmail.com, Tel: + 91-22-25575618

forces of casteism, communalism and regionalism. In philosophical terms, Indian thought is largely considered not as philosophy proper but as being concerned with something larger, something as profound and deep as life itself. The entire energy of thinking is perceived to be concentrated on the final goal of attaining enlightenment or freedom, of liberating the human spirit from its earthly bondage. In contradistinction with the more materialistic and theoretic West, the basic point of Indian philosophical reflection is considered to be the practical and experiential processes through which enlightenment and liberation are achieved. At other times it is claimed that Indian traditions are concerned with categories and themes which are part of the Western intellectual world or, more radically, that there is no such thing called Indian philosophy. Interestingly this debate also affects other non-Western philosophies (cf. Raud 2006).

To this picturization have been two types of responses in the main. One has been undertaken by Indologists (cf. Muller 1883/1991) and Romanticists (cf. Berger 2004 and Tzoref-Ashkenazi 2006) who to different degrees concurred or disagreed with the assumption that India does not have a philosophy at all. A second response came from a nationalist persuasion. Fuelled by colonialism and by a burning desire to stand independent after 1947, this response was to show that not only was there a corpus which could be called Indian philosophy but that this philosophy was also something unique - it was distinct from that of Western philosophy, it included very easily many of the concerns and categories of Western philosophy, it transcended them, and in some respects improved upon them successfully. In this paper we look at some of the main lines of argument of the nationalist reading of Indian philosophy in its more orthodox moments before surveying some of the critiques of such a reading. It is hoped that such an endeavour would act as a stimulus for further Indian philosophizing in its own terms.

The Received Wisdom: Classical Philosophy

In their classic work, An Introduction to Indian Philosophy (1939/ 1984, pp. 12-25), Satischandra Chatterjee and Dhirendramohan Datta, outline the most characteristic formulation of what is generally understood by Indian philosophy. This characterization forms the background to their exposition of what is considered to be the fount

of most Indian philosophical work in the classical sense, namely, the ‘systems’ such as Caravaka, Jaina, Bauddha, Nyaya, Vaisesika, Sankhya, Yoga, Mimamsa, and the Vedanta. It is interesting to note that Chatterjee and Datta feel that the following characteristics overwhelm the differences which are as a matter of fact easily perceptible in the philosophies of the different systems.

The chief feature of Indian philosophy is its practical motive – how it can act as a guide to enlightened living on this planet. This however does not mean that theoretic concerns are not important; the voluminous discussions on the theoretic branches of Western philosophy such as metaphysics, logic and epistemology are proof of how seriously the Indian philosopher took theoretical concerns in his way to attain knowledge of an enlightened life. The practical has overriding influence because it is unhappiness with the existing order of things, in human society and in the larger universe, which has acted as the spring for classical Indian philosophizing.

The authors seek to rectify the characterization of Indian philosophy as being pessimistic in nature. Truly it is pessimistic because it secures its need from the unhappy state of human and natural affairs. However the intellectual labour does not end there because the entire effort is a search for an ‘actable’ path towards getting out of this uncomfortable situation. Furthermore what helps Indian philosophy from degenerating into scepticism or pessimism is the belief in a spiritualism which permeates the entire moral order of things. It is this belief which gradually coagulates in the famous law of karma which characterizes almost all the schools of classical Indian philosophy:

in its different aspects may be regarded as the law of the conservation of moral values, merits and demerits of actions. This law of conservation means that there is no loss of the effect of work done (krtaparanasa) and that there is no happening of events to a person except as the result of his own work (akrtabhyupagama)” (Chatterjee and Datta 1939/1984, pp. 14-15).

An idea in classical Indian philosophy, no less important than the law of karma, is that ignorance of reality and the true nature of the self is a cause of much of our bondage to the material and phenomenal world (and the attendant sufferings). Liberation from the process of birth and re-birth is the surest way to moral perfection and real happiness. However, as is to be expected, mere theoretical knowledge of what causes birth and re-birth is not enough – the practise of meditation on the truths and a life of restraint and self-control is of utmost importance. In this context the elaborate science of yoga is found to be most helpful. Guided self-control, restraint on impulsive likes and dislikes, curbing the sensitivity of our indriyas or sense-organs, counter-posing of new good habits to overwhelm die-hard old habits, are all geared towards abhyaysa or repeated efforts in the right direction. Yoga then is the practical endeavour to cultivate a morality which is not negative or restrictive but which is aimed towards the enhancement of good habits and positive virtues.

Yoga therefore not only is the encouragement of abstinence from injury to life, falsehood, stealing, sensuousness and covetousness but also the cultivation of the purity of body and mind, contentment, fortitude, study and resignation to God. In consonance with all this therefore the greatest goal of Indian philosophy is moksa or liberation. Moksa can either be taken to be the removal of all sufferings or a state of positive bliss.

An Introduction to Indian Philosophy is also greatly taken up with the commonly perceived dependence of classical Indian philosophy on the authority of tradition. The classical Indian systems of philosophy are usually grouped into the nastika and astika traditions. The Caravaka, Jaina and Bauddha systems which reject the authority of the Vedas are grouped into the nastika tradition whereas those schools not rejecting Vedic authority are grouped under astika tradition. From the latter arise schools which are directly based on Vedic texts and schools based on independent grounds (e.g.

Sankhya, Yoga, Nyaya and Vaisesika). Amongst the schools which are based directly on Vedic texts is the Mimamsa which emphasizes the ritualistic aspects of the Vedas and the Vedanta which emphasizes the speculative aspects of the Vedas.

Chatterjee and Datta discuss the two views that philosophy derives its authority from ordinary everyday experience and from authority of especially enlightened persons. The Nyaya, Vaisesika, Sankhya, Caravaka and the Bauddha and Jaina schools (to a large extent) believe that philosophizing has to be based on normal life experience. On the other hand the Mimamsa and Vedanta systems believe that on some matters of utmost gravity (e.g. God and state of liberation) it is best to rely on the authority of saints who have had direct experience of the true reality. Nonetheless, Chatterjee and Datta argue, almost all systems rely on reasoning as the chief method of their speculations and other endeavours. Those schools relying on the authority of the Vedic texts may appear dogmatic but even when they are left on their own grounds they can provide independent support for most of their arguments.

They are also insistent that, despite the tremendously practical orientation of classical Indian philosophy, the details of the numerous schools of thought indicate the catholicity and rigorousness of philosophizing. Each school began with a comprehensive consideration of the positions of other schools on a certain proposition forwarded by the school under consideration and each of these positions was considered with caution and care before being dismissed (Chatterjee and Datta 1939/1984, p.4). A certain atmosphere of philosophical collegiality was thus present and this has been one of the reasons for the wealth of the philosophical tradition in India.

Now, although the Vedas formed a major and basic reference point for the systems of classical Indian philosophy it was left for another text - Outlines of Indian Philosophy (1932/1983) by M. Hiriyanna - to mark out the Vedic territory vis-à-vis Indian philosophy clearly. In his account Hiriyanna takes pains to indicate the antiquity and foundational nature (for Indian philosophy) of the Vedic corpus. The origins of Indian philosophy are to be found in the hyms of the Rgveda composed by the Aryans who had settled down in the northwestern parts of the Indian sub-continent somewhere in the middle of the second millennium before Christ. Moreover

the “speculative activity begun so early was continued till a century or so ago, so that the history we have to narrate...covers a period of over thirty centuries” (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, p. 13). The antiquity of Indian thought is marked by three stages. The death of the Buddha marks the end of the Vedic period, during which much of the literature is supposed to be revealed by the gods, transmitted down generations orally, and are considered to be of remarkable accuracy. The period following is known as the Sanskrit or classical period in which the works are more extensive, detailed and systematized. This period is to be divided into two stages, namely, the ‘age of the systems’ and the ‘early post-Vedic period’ (Hiriyanna 1832/1983, p.15).

Another feature which is stressed is that there is very little information regarding the lives and characters of the philosophical thinkers in this entire history – they are no more than points of light on the vast canvas of the history of Indian philosophy (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, p. 14). It is assumed that personalities are the products of their times and historical contexts. Hence Indian philosophical accounts reveal a complete absence of biographical information.

In the Vedic period, pre-Upanisadic thought usually is considered to arise from the two sources, namely the very early Mantras and the later Brahmanas (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp. 29-32). The Mantras are said to be preserved best in the Rg-veda and Atharva-veda samhitas – they are largely religious songs in praise of certain deities and are meant to be sung at times of their worship. Unlike the Mantras the Brahmanas are written in prose style and are liturgical in character. They are elucidations of what the Mantras sung and are important in the sense that they act as guides to the rituals to be performed as per the Mantras. However the Brahmanas do a little more than this and indulge in some speculation, which gives us an indication of philosophizing at such an early age. Although the Brahmanas include the Upanisads the contents and orientations of both are different. The interesting thing about Vedic religion is that it formed, in its worship of natural powers deified as gods, a continuous chain with the gods of the Europeans and Indo-Iranians which were evident before the Aryans had settled down in north-western India. In this pantheon of natural deities there is

no supreme God although there is an effort to classify the gods into gods of the sky, gods of mid-air and gods of the earth.

Hiriyanna however recognizes a couple of facts of crucial philosophical importance in the nature worship of the early Vedas. In contrast to the Indo-European or Indo-Iranian pantheon the Indian mind does not conceptualize the natural deities in their fully anthropomorphic form. They are still kept somewhat in the hazy area between nature and man because the Indian thinkers still wanted to fully understand the nature of the universe and man’s relationship to it and therefore wanted to keep some space for such speculation. This apparently created the ground not only for intense philosophizing but also provided scope for the wide variety of problems which could be presented as challenges to the philosophical endeavour. Somewhat later the Indian thinker apparently loses interest in the plurality of gods of nature and seeks to identify the one God who controls or rules over the others. However it is noticed that there is still an absence of one supreme God. Rather the predominance of the more important gods, such as Indra and Varuna, continue. The main difference now is the search for the common power which works behind these multifarious gods. This is, for Hiriyanna, ‘philosophical monotheism’ as distinguished form the usual monotheism where there is belief in one only God (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, p. 39).

The Outlines of Indian Philosophy detects another important philosophical precursor in the literature of the Pre-Upanisadic phase. Philosophical monotheism, it contends, still provides a leeway for dualism because it posits a unitary godhead or the power thereof above the other gods who are set against nature and man. But there is also evidence of a more powerful monotheism, namely, monism in the Indian thinkers of this period:

“There are in it at least two distinct shades of such monistic thought. To begin with, there is the pantheistic view which identifies nature with God...The central point of the pantheistic doctrine is to deny the difference between God and nature which as we have shown is the necessary implication of monotheism. God is conceived here not as transcending nature but as immanent in it. The world does not proceed from God, but is itself God...[In the other view on monism], unlike the pantheist, the principle of causality, not only

traces the whole universe to a single source but also tackles the problem of what its nature may be. All opposites like being and non-being, death and life, good and evil, are viewed as developing within and therefore as ultimately reconcilable in this fundamental principle. In regard to the origin of the universe, we have here, instead of the view of creation by an external agency, the view that the sensible world is the spontaneous unfolding of the supra-sensible First Cause” (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp. 41-43).

Two other significant features – for philosophy – are noticed in this period. The first is the notion of rta. It indicated not only an effort to understand the machinations of nature as a cosmic order but also as somehow indicating a moral order. “The Vedic gods are accordingly to be viewed not only as the maintainers of cosmic order but also as the upholders of the moral law. They are friendly to the good and inimical to the evil-minded, so that, if man is not to incur their displeasure, he should strive to be righteous” (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp. 33-34). The second is that in addition to the monotheistic and monistic tendencies in the Vedic corpus there existed outside its ambits a whole world of heterodox thinking and philosophers – ‘Vedic free-thinkers’ – who challenged much of the philosophical presuppositions of the Vedic thinkers (Hiriyanna 1932/ 1983, pp. 43-44). It is interesting to note here that the response to the heterodoxies was vicious and exclusionary.

In the Upanisadic phase of the Vedic period there is a rebellion against the ritualistic and naturalistic forms of worship and thinking of the early Vedic times. Although there is a great degree of diversity between the roughly two hundred odd Upanisads, the teaching is largely monistic and idealistic in nature. The older gods do not disappear but are made subservient to the one powerful reality – Brahman – which has now been discovered. Brahman is the primary cause of the outer universe and atman is the inner locus of man. Eventually these two terms are used synonymously so that Brahman and atman, the outer and the inner, become immanent in each other. Reality is one. The philosophic Absolute is an inner principle of the atman and not an object of adoration and worship distinct from it.

“The idea of God in the Upanisads therefore differs fundamentally from the old Vedic view of deva...The Upanisadic god is described

as the ‘inner ruler mortal’ (antaryamyamrtah) or the ‘thread’ (sutra) that runs through all things and holds them together. He is the central truth of both animate and inanimate existence and is accordingly not merely a transcendent but also an immanent principle. He is the creator of the universe, but he brings it into being out of himself as ‘the spider does its web’ and retracts it again into himself, so that creation really becomes another word for evolution” (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, p. 82).

The practical arm of Indian philosophy was evident very early on – in the Upanisads. Intellectual attainment of Brahman is inconceivable without the practice of austerity, meditation and renunciation (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp. 72-81). The Taittiriya Upanisad recommends three different ways for the attainment of immortality, namely, devotion to truth, penance and Vedic study. The Isa Upanisad clearly indicates that renunciation does not mean withdrawal from all activity but pursuit of the truth through incessant exertion, without hoping or desiring any rewards thereof. Evil is the result of perceiving the world and the universe through the finite self – aham-kara – which distorts the picture of the one reality, Brahman. Goodness, or the overcoming of evil, consists in attaining Brahman-realization or moksa. Moksa is a stage in this life wherein the individual continues to witness variety and finiteness but is not deluded by it because he has recognized the fundamental unity in them all. To facilitate the path towards moksa, cultivation of detachment and attainment of knowledge are terribly important. They constitute the practical means of achieving the practical goal of all philosophy – relief from delusion and suffering, moksa, peace. Detachment from the world and from the rewards of our actions, pursued through the asrama stages of student (brahma-carya), householder (garhasthya) and anchorite (vana-prastha), are the means towards vairagya. Similarly, acquisition of correct knowledge is essential for treading the path towards moksa. Study of the Upanisads from an appropriate teacher, continued reflection on what is learnt, and meditation for inner realization are essential steps in the gaining of right knowledge and the immediate perception of unity amidst diversity.

The philosophical development in the Upanisads is followed by the long early post-Vedic period. The philosophical and religious

teachings of this period mark both a continuation of Upanisadic precepts as well as radical departures from them. To begin with, many of the doctrines are meant for all classes of people irrespective of sex or station. Moreover philosophy becomes more realistic so much so that even the idealistic schools acquire more of a realistic flavour which often gets accommodated in a well-defined theism (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp. 87-88). The literature of this period, besides those of the heterodox sects, is to be found largely in the Upanisads and the Soutra-sutras, Grhya-sutras and the Dharma-sutras, and the epics such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. The Upanisads break up into groups, each group dealing with selected topics which were not dealt with by the earlier Upanisads or were insufficiently dealt with by them. The Sroutra-sutras systematize the ritualistic aspects of the Brahmanas, the Grhya-sutras ceremonies and other ritual aspects of family life, whereas the Dharma-sutra deals with customary law and morals (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp. 88-89). The epics are said to contain almost all the knowledge which is to be found in the other texts.

The ritualism of yore is found to be – in the philosophical tradition of the early post-Vedic period – more exacting and conservative in nature. Diligent attention is paid to the codification of old laws and customs and the rituals are made more specific and rigid. Adherence to Vedic ceremonials is considered to be of utmost importance. Absolute monism is prevalent but “the general tendency is to lay stress upon the realistic side – to look upon the physical world as an actual emanation from Brahman – and to dwell upon the distinction between the soul and Brahman as well as that between one soul and another” (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, p. 93). The tendency to convert the abstract Absolute into a personal God becomes more secure in this age and thus we notice the appearance of the all-powerful deities such as Brahma, Siva or Rudra, Visnu and SriKrishna. The practical dimension to the philosophy of this time is summed up by the three-fold path, namely, karma, yoga

and bhakti (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp, 107-115). Karma refers to the sacrificial rites, customs and ceremonies which had by then become firmly a part of the orthodox tradition. Yoga refers to the elaborate techniques and skills of meditation which when yoked to right knowledge lead one on the path to immortality. Bhakti refers

to the single-minded devotion, often in groups, towards the personal God. Loving this God and in turn being loved by Him establishes the faithful and the lord in a tight embrace of devotional bliss. The epitome of the theoretic and practical dimensions of the philosophy of this period is of course the Bhagavadgita. A combination of Vedantic, Bhavagavata theistic and older Sankhya

thinking the Gita is considered to be one of the most important texts of classical Indian philosophy. Detachment from the ensuing results of one’s action whilst single-mindedly pursuing one’s social obligations and duties is the main practical philosophical lesson taught by this text. The Gita teaches “…not renunciation of action, but for renunciation in action” (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, p. 121). The significance of this karma-yoga was that none of the philosophical systems which followed discarded this idea.

The aforesaid elaboration of the significance of the Vedic corpus in the Outlines of Indian Philosophy is integral to the way in which it conceptualizes the classical Indian philosophical endeavour. As a challenge to the characterization of Indian philosophy as negative and pessimistic, the text emphasizes the variety and richness of Indian speculation. There is apparently no shade of thinking or feeling which is left out by the Indian philosophical corpus. Almost the entire corpus is marked by alternations of pessimism and optimism. This has been facilitated by the great degree of interpenetration of opposed points of view in the long course of history of the corpus (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, p. 16).

One of the most commonly held view about Indian philosophy is that religion and philosophy are, in it, one and therefore there is no philosophy in the strictest sense. Hiriyanna takes great pains to show that religion and philosophy are indeed separated in the Indian context (cf. Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp. 17-26). This is very clear if religion is taken negatively to be a set of moral precepts which are forbidding and punitive in nature. However if a religion is the straining towards an ideal which is to be based on right living then, indeed, philosophy and religion are one in India. For the over-arching goal of Indian philosophy is not to grasp theoretically the meaning of liberation - moksa or nirvana – but to realize it through the individual's own experience. The source of this particular amalgamation lies in the origin of Indian philosophy, which did

not arise from wonder or curiosity of the world but from an acute sense of discomfort and unhappiness which the given order of things generated. Philosophical formulations were directed towards the remedy of these difficulties.

The second most peculiar thing about the moksa ideal was that it was not considered to be a stage to be attained in the after-life but as something which each individual must strive for in the present life itself. This enlightenment, even in the most hidebound of realistic doctrines, was a desirable state of things because it filled the world with a new sense of understanding and purpose. Philosophy in India thus contained the ideals of both intellectual satisfactions which were further geared towards a possible improvement in life.

A corollary feature of Indian philosophy – Hiriyanna contends – is that it inculcates a sense of asceticism and renunciation, no matter how many the differences in the substances of the respective theories. They agree on renunciation but assign different reasons for it. The nastika schools felt that man should turn away from this world once and for all irrespective of his circumstances whilst the nastika schools argued that the ascetic ideal is to be only slowly and progressively achieved, after the individual has crossed through the other more mundane stages (i.e. student and householder) in life.

This leads to a crucial distinction between Indian and Occidental philosophies. Whereas renunciation may appear to be pessimistic and other-worldly it is actually a life-affirming ideal. It is a practical measure, guided by the most sharp and elaborate logical and metaphysical arguments, to secure for a person enlightenment in this life and in this world. This is very different from the Occidental religions which promise saving and grace in a world different from the one which the concerned person inhabits.

One of the innovations which Hiriyanna conducts over Chatterjee and Datta is reflection on the relationship between rights and duties as an explanation of the combination of the dogmatic and optimistic, of the practical and the theoretic, of logic and ethics. At the level of enlightenment attained through asceticism and renunciation the distinction between individual and society gets erased so that all sense of the individual’s obligations towards society and personal and social rights accruing to him get negated. Accordingly morality

as ordinarily conceived is transcended: “…according to the systems which deny the individual self in one form or another, the very notion of obligation ceases to be significant finally, the contrast between the individual and society upon which that notion is based being entirely negated in it...In the other systems which admit the ultimacy of the individual self but teach the necessity for absolute self-suppression, the consciousness of obligation continues, but the disciple devotes himself to its fulfilment with no thought whatsoever of his rights. That is, though the contrast between the individual and society is felt, that between rights and duties disappears;...”(Hiriyanna 1932/1983, p. 23).

Hiriyanna argues further that the moral in Indian philosophy errs on the side of duties rather than on the side of rights. The individual’s obligations extend to the whole creation of the universe rather than being confined only to individual human beings. The philosophy is not only to love one’s neighbour but to also realize that every living thing is one’s neighbour. Therefore the keyword is duties towards others rather than assertion of one’s own rights. The idea is to transcend social morality and personal egoism and take care of one's responsibilities to all living beings. This sense of duty is at the root of ahimsa – the principle of non-injury.

Hiriyanna’s detailed exposition of the Vedas and the Upanisads, by way of showcasing Indian philosophy, enables him to come to a conclusion which is of tremendous appeal and importance to the nationalist project. He speaks of the final triumph of Vedanta and considers this to be a natural progression from all the schools which had preceded it and influenced and transformed it. The Vedanta - the end of the Vedas, that is, based on the Upanisads, is the highest type of the Indian ideal because it stands for the triumph of Absolutism and Theism. In practical terms the triumph of the Vedanta has meant the triumph of the positive ideal of life by identifying the interests of the self with those of the whole (Hiriyanna 1932/1983, pp. 25-26).

Another variant of the received nationalist reading is provided by Karl H. Potter in his ‘Attitudes, Games, and Indian Philosophy’ (Potter 1956). He asserts that most Indian philosophical statements are of a non-literal character and it is this characteristic which encourages Western readers to designate most of Indian philosophy

as religion. For those with a more pro-Indian stand this phenomenon produces the opposite result, that is, an effort to provide factual meaning related to the different fields of philosophy (e.g. logic, metaphysics and epistemology) in order to recover some meaning from what appears as religious mysticism for most of the time. Potter feels that we should rather try to recover the multiplicity of meanings which undergird much of Indian philosophical statements.

He also asserts that much of Indian philosophy is practical in nature and it is in the details of the practicalities that the meanings of most of the technical terms must be sought for. The rigid systems of the caste and the four stages of life (asramas), along with the attendant details of how a person should conduct his daily life, indicate that Indian philosophers were more concerned with how a person lives his life and with what attitudes than with technical or theoretic elaborations of the relevant terms and statements. This is why, Potter says,

“Western readers have been exposed to Indian thought for the most part through a series of textbooks suited perhaps to the Western outlook but most unsuited for reproducing the Indian’s own frame of reference. The result has been that the average readers, especially those trained in Western philosophical techniques, judge such Indian ideas as they happen to come in touch with by standards that are completely inappropriate to the attitude in which they actually occur. This also accounts for the fact that most translations of Indian materials into English are inadequate in so far as they fail to communicate the characteristic attitude in which the idea framed are to be understood. English has few words for attitudes, and there is no developed technical vocabulary containing terms for them. Consequently, the translator must manage with words whose precision is familiar only within the model of fact-stating discourse, and the consequent judgements of Indian materials tend to be made in terms of that model” (Potter 1956, pp. 240-241).

A very important feature of these attitudes in Indian philosophy is that they are like games, each with their own rules and requiredness. It is important to know these rules and requirements, just as much as it is important to know that one must become part of any game one wishes to know because one cannot know an attitude or game by being a spectator. The languages of a spectator have

the danger of imposing its own rules and categories on the subject and distort its matter. Understanding the game therefore does not mean analytical understanding but an understanding based on sympathy, an understanding with a genuine desire to know exactly what these games and attitudes mean and say. In this context, therefore, illustrations, myths and metaphors can act as good guides to right knowledge.

Now the nature of Indian philosophy as made out by Chatterjee and Datta, Hiriyanna and Potter continued to flourish in India beyond the classical age. Seats of learning, commentaries and expository works, and development of new genres of literature (within the larger ambit of the classical systems) were noticeable (Thapar 2002, pp. 466-474). During the Mughal rule there was a great degree of inter-exchange of Persian and Sanskrit literature although the focus was more on poetry, literature and the epics (Majumdar 1946/1991, pp. 571-577). SriKrishna and Rama cults and the Vaishnavite movements were the highlights of Indian religion and philosophy of the times. The nationalist persuasion however does find much merit in deeply examining these trends, especially the development under Muslim rule, and straight away jumps to the modern or British period.

The Received Wisdom: Modern Indian Thought

Dhirendra Mohan Datta (Datta 1948, pp. 555-556) argues that the initial impact of British rule in India on Indian philosophy was inimical for its growth because there was the British emphasis on learning modern and classical European philosophy. It was only in the eighteenth century with the rise of the Indologists or Orientalists such as F. Max Muller or William Jones that the hidden treasures of Indian philosophy and religion especially in the Sanskrit texts and academies were gradually re-discovered. This has led to the growth of comparative philosophy between the East and the West. However this has meant a tremendous challenge to Indian philosophers and they have consequently found it difficult to develop newer ideas in Indian philosophy. Those who have somewhat succeeded have been able to do so because of the catholicity of their approach. In this sense Indian philosophy in modern times, contends Datta, represents the “evolution of a world philosophy.”

Amongst the latter he takes the case of Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

who is known for his idealistic view of life. Radhakrishnan is a unique case because he was both a historian of philosophy (cf. Radhakrishnan 1929/1990) as well as a philosopher developing his own ideas. Here we take him up as a philosopher in his own right, especially in the comparative aspect (cf. Radhakrishnan 1939/1992). In an engagement with classical Indian and Western philosophies he develops his notion of the Absolute to not only correspond to the Brahma of Vedanta but also to the dynamic spiritual energy which evolves the world from non-being to being through the successive stages of matter, life, consciousness and self-consciousness. The Absolute according to him, unlike Western idealists, is freedom because it expresses its possibilities out of its own choice. Moreover, following “Sankara’s distinction between Param Brahma and Isvara, Radhakrishnan also makes the distinction between the impersonal Absolute and the personal God, the creator of the world. But unlike Sankara and Bradley, and very much like the average Hegelian, he holds that God is not an appearance of the Absolute” (Datta 1948, p. 557).

Drawing on the works of Indian and Western mystics, Radhakrishnan believes that perfection is attained by religious intuition in which intellect, will and emotion are fully integrated. Herein man is one with the spirit in him. Accordingly he holds, with Sankara but against Bergson, that intuition is not in opposition to the intellect – rather it is the highest perfection of the intellect. One of his greatest contributions therefore has been to search for the common intuitive bases of the world’s greatest religion and philosophies and then show that they are the manifestations of one true unity. For him the unrest in all the quarters of the world is a result of falling away from these basic intuitive bases. The West rapidly degenerated into crass materialism because of the overpowering place given to the intellect and a breakdown in the world of the spirit. The East witnessed a degeneration of its world of spirit into superstition and ritualism. Accordingly what is required is a new religion which would give adequate voice to the spirit in a world of matter, a religion which would integrate the ideal and the real. Interestingly, Datta contends, this form of dynamic philosophy was very much evident in the Vedanta of Sankara and Ramanuja as also in some forms of Saivism and Tantrism. However under the

influence of the realist and activist West, most Indians have abandoned the idealist outlook because they feel that idealism has been at the root of many of India’s problems. By a strange quirk of fate, however, many Indian philosophers toady still hold on to variants of the Vedanta rather than explore the more realistic Nyaya-Vaisesiska doctrines.

Another example of modern Indian thought is said to be Sri Aurobindo. His basic doctrine is an amalgamation of the philosophy of action with the detachment of the Gita with the idealism of the Vedas and Upanisad. His integral approach contends that the finite is an expression of true Reality, that both materialism and asceticism are one-sided and not complete, that change and permanence are both real, and that Brahma enjoys self-manifestation and not only expresses itself in all forms but also includes all the forms. Through the creative force of God the world has gradually evolved from the material to the mental and spiritual. Consciousness enables man to realize his uniqueness but he has to go along with evolution to become spirit, that is, become one with God. Thankfully man is aware of the divine in him and this is evident in all religions. Hence man can select any religion according to his temperament and proceed to move higher and higher in his mental planes. Having attained divinity man is responsible for helping the whole of mankind reach that stage of spiritual freedom and bliss. Datta notices here a throwback to the idea of Boddhisattva wherein individual liberation is rejected in favour of social upliftment and liberation.

The last great modern Indian philosopher, according to Datta, is Krishna Chandra Bhattacharyya. Inspired as much by Kant as by the Upanisads and the Jainas, Bhattacharyya regards as ultimate the consciousness which transcends both the subject and the object. However this supreme consciousness is not reality in the objective sense of the term. Being neither definitive of subjectivity nor of objecthood, consciousness is called the Indefinite. In contrast most of the Western attempts at the Indefinite stop short of the Absolute Indefinite and assign it a place amongst objects or reals. Knowing is the unknown and therefore cannot be known in the ordinary sense. The Indefinite is always present against the background of everything known by us and hence we become conscious of it in the negative sense. It is fairly difficult to say why the Indefinite

gives shape to the definite but we can see how the boundaries between the known and the unknowable are constantly shifting. Therefore the Indefinite can only be known by negative attention, by self-denial.

“Corresponding to three stages of positive attention and one of negative attention, there are four fundamentally different philosophical attitudes and schools. Positive attention which is fixed on objects alone breeds realism of the pan-objective kind; that which alternates between objects and the subject as determined by their contrast gives rise to dualism; that which simultaneously views the objects and the subject as a complex system generates a philosophy of the Hegelian type. But when all determinates, objective and subjective, are negated and attention is withdrawn from them as illusory, there ensues a reversal of positive attention into the negative kind, and the Indefinite, transcending the subject and object, is realized as the truth. Monistic Vedanta exhibits this last type” (Datta 1948, p. 563).

Consciousness, then, for Bhattacharyya, is of four types, namely empirical thought, pure objective thought, spiritual thought and transcendental thought (Datta 1948, p. 564). The empirical world belongs to science whilst the contents of the remaining three grades of consciousness are the object of philosophical analysis. Datta feels that here Bhattacharyya resembles Kant and the logical positivists. A synthetic world-view is beyond the capacity of philosophy and can be known only through a poetic imagination which yields no knowledge. Spiritual progress is the gradual process of realizing the freedom of the subject from object and from subjectivity itself through the realization of the Absolute. There is a differentiation of the supreme consciousness into knowing, feeling and willing. Accordingly there are differences between religions and philosophies and thus quarrels amongst them are unjustified.

Besides these scholastic or ‘professional’ philosophers, Datta identifies another set of reformer-philosophers in the Indian firmament that can be said to be definitive and characteristic of much of Indian thought. Responding to the challenges thrown up by British colonial rule, Christianity and Orientalism, these reformer-philosophers were more in tune with the broader social, political and economic currents of the times. They were sensitive to the groundswell of protest

against British imperialism and the consequent socio-economic and cultural nationalism, and in that sense, they can be accurately located as part of the nationalist persuasion in India philosophical and religious trends.

Two of the founders of the ‘Renaissance’ in colonial India in the nineteenth century – Raja Rammohan Roy and Dayanand Sarasvati – sought to develop philosophy and religion along new lines which were based on theistic Upanisadic teachings and on Vedic ritualism. Roy’s faith was a rationalized and modernized theistic worship of the Upanisadic Brahma in His personal aspect. In contrast to this elite religion for the educated people, Sarasvati aimed to popularize Vedic ritualism and monotheism amongst the masses. Opposing Islam and Christianity but at the same time arguing against the caste system and idol worship Sarasvati based his philosophy on the three fundamentals of God, soul and nature.

It is however the philosophy of Ramakrishna Paramhansa and his disciple Swami Vivekananda (cf. Radice 1999 and Bhattarcharya-Mehta 2008) which caught the imagination of both the Indian masses and the literate classes, as well as Orientalists and other sundry kin in the West. In their work is stressed the fundamental unity of all religions and philosophies and this is based on a revival of the monistic Vedanta of Sankara. Whilst Paramhansa himself attained enlightenment through practice of asceticism of all the major religions - thus proving the unity of all paths - Vivekananda “introduced into Hinduism the missionary zeal of Christianity, imparted to the monistic Vedanta a practical shape by emphasizing its positive aspect – that all is Brahma, and, therefore, that service of man as God (nara-narayan) is better than quiescent meditation” (Datta 1948, p. 567). According to him the Vedas contained the eternal truths and all religious and metaphysical notions were inherent in Vedanta. The three successive stages in man's spiritual progress are duality, qualified monism and monism. Dualism was the first stage of the Indian tradition and in that sense dualistic Islam and Christianity were part of the expressions of Vedantic truth. Accordingly all religions and philosophies are true and all divisiveness is the result of ignorance. For Vivekananda Truth alone is God and the whole world his country/nation. In this sense he visualized a new faith, a new Veda and a modernized Hinduism.

Drawing inspiration from the teaching of the Upanisads, Rabindranath Tagore played a major role in the philosophical and spiritual revival of the country especially through his contributions to education, the arts and rural development (cf. Ray 1967 and Dayal 2007). Opposing impersonal absolutism, puritanism and asceticism he drew those lessons from the Upanisads which stressed the relationship of joy and love between the finite and the Infinite. Accordingly he abhorred narrow patriotic nationalism and argued for the universal nationhood of world-man. It was, however, left to Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to work this philosophy of tolerance, love and peace into the fierce alleys of politics and international relations. Gandhi argued for a politics which would help an Indian to become closer to his own spirit and to other human beings across the world. Preaching that violent means begat violent ends, Gandhi worked out his philosophy of satya, ahimsa and svaraj

(Iyer 2004). Satya or truth was the supreme principle for Gandhi in ethics, politics and religion: “The truthful man who in his every attitude and action is genuine and straightforward is the objective man in the highest sense of that word. The utmost veracity can come only from the recognition of the common basis of cosmic order and natural law, all true community life, every meaningful personal relationship, growth in self-awareness in daily life as well as the highest mystical communion. Satya is the active power of evolution in the universe, and it must be likewise in society” (Iyer 2004, p. 176).

The other most important component of Gandhi's philosophy was ahimsa or non-violence. He was quite aware of the centrality of this outlook to both orthodox and heterodox philosophies of classical India, but his demand of having the same measure for saint and householder and his interest of bending philosophy to social reform helped him to argue for the veracity of ahimsa independent of hoary philosophies. In its negative sense ahimsa is the abstention from violence and in its positive form it is the ability to love even one’s opponent or enemy. In its positive sense it is the expression of the greatest love and charity. Ahimsa therefore demands renunciation, non-attachment and the ability to undergo suffering. However it is through the philosophy of svaraj and swadeshi that Gandhi was able to formulate his own distinct brand of

nationalism. He was able to establish a close relationship between the two concepts, between individual rule and individual self-reliance: “Instead of assimilating the concept of freedom to that of community by merging the individual into an organic conception of society, he derived the very notion of communal self-reliance from his doctrine of individual self-rule, and showed how the pursuit of swaraj must necessarily involve the acceptance of swadeshi, and yet the former must be taken as logically and morally prior to the latter. He achieved this result by basing swaraj upon satya, i.e. , linking the notions of freedom and of truth, secondly, by deriving the doctrine of swadeshi from his concept of ahimsa (emphasizing its positive rather than its negative connotation) and thirdly, by basing the connection between swaraj and swadeshi upon the relationship between satya and ahimsa” (Iyer 2004, p. 347).

Datta can now proudly recall his review of modern Indian thought and state how Indian philosophy today is the result of a creative blend of the Eastern and the Western philosophical genius. The dynamism and realism of the West has helped to rejuvenate Indian philosophy and religion which had otherwise degenerated into quietism and defeatism. Therefore, the “…main trends of Indian thought which deserve special attention at this critical age of our planet are (1) its attempt to base philosophy on all aspects of experience; (2) its practical insistence that philosophy is for life and must be lived in all its spheres, private, social, and international; (3) its emphasis on the necessity of controlling the body and mind, the necessity of moral purity and meditation, to make philosophical truths effective in life; (4) its recognition of the fundamental unity of all beings, particularly mankind, and the consequent consciousness that our moral or religious duties are toward all, and not simply to the members of our own group, country, or race; (5) its conviction that the Ultimate Reality manifests itself, or can be conceived, in different ways, and consequently that there are divergent paths to perfection any one of which can be adopted in accordance with one's inner inclination; (6) its belief that political freedom and material progress are necessary, but only as a means to ultimate spiritual peace and perfection, so that they should be attained in ways not detrimental to the latter; and lastly (7) its contention that the ultimate aim of every individual should be to perfect himself

with a view to raising the world to perfection (Datta 1948, pp. 571-572).”

This appears to be a comprehensive manifesto and road map for an emergent discipline. However it is surprising that, in this nationalist recounting of the wonders of Indian philosophy and its relationship to the West, there is not a mention of Islamic philosophy worth its name. Despite being under Muslim rule for centuries, with evidence of literary and philosophical cross-fertilization, there is no account given of how Islamic philosophy in the Indian sub-continent made it its home and flourished with a standing of its own. Neither is there any story line of how Islamic philosophy benefited from translations of Sanskrit classics and how non-Muslim Indians made use of Islamic teachings. Nor do we get to read how Islamic thought and culture responded to the very same stimuli from the West under British rule in India. Is all Indian philosophy – classical, medieval and modern – only non-Islamic? This is to miss out, in the nationalist account, a very large part of the story. We fail to learn the mutations in high Islamic philosophy in India and, surely, we do not get to hear the enormous impact of sufi philosophy, which played such a large role in converting millions of Indians into Muslim Indians. A similar silence pervades the nationalist project of Indian philosophy vis-à-vis the philosophies of tribals, dalits, women and, of course, the unique peoples of the North-East. The power of this omission continues till today. Bhushan and Garfield (2011), in their survey of Indian philosophy in the colonial period (‘from Renaissance to Independence’), do not mention Islamic philosophy, leave aside dalit and tribal philosophies. We leave these lacunae for another tale and briefly indicate here some of the other contentions made of the nationalist project from the philosophical, materialist and ‘subaltern’ angles.

Critical Lights: Philosophy, Materialism and the ‘Subaltern’

Daya Krishna (1965) is taken up with the fact that Indian philosophy is hardly taken seriously world-wide as philosophy as such and lays the blame squarely at the feet of those philosophers who have written Indian philosophy as if its entire philosophical corpus is geared towards an understanding of and a facilitator of gaining enlightenment and freedom, a liberation of the entrapped soul – moksa. His piece

thus has the potential of being a critique of an important assumption of the nationalist project. Krishna takes issue with the definitive work of Potter (Presuppositions of India’s Philosophies)(Potter 2002) which persuades itself that the main research question, in this context and regard, is how one reconciles India’s elaborate philosophical architecture with its stated final goal of moksa (Krishna 1965, pp. 38-42). Potter apparently feels that Indian philosophy is meant to calm the intellectual doubts of those who are pursuing moksa. Krishna feels that this limits Indian philosophy merely to answering the sceptic’s questions. Moreover if the questions of the sceptical moksa-seeker are intellectual and thus have to be answered conceptually there arises a gap between the speculative nature of this enterprise and the moksa-ideal. Another issue is that since this is the real nature of the philosophical enterprise they are in a sense not necessary and should not be allowed to rise in the mind of those in pursuit of the true ideal – moksa. There is a view gaining ground, according to Krishna, which sees the philosophical enterprise itself as a meaningless cognitive enterprise and a waste of time and he advises Potter to bring in this issue in the context of moksa and philosophy. Moreover, another assumption which seems to lie hidden underneath Potter’s claim is that the rational nature of man is an obstruction to the non-rational and non-intellectual pursuit of moksa. But Krishna is of the opinion that seldom have fundamental things in life got obstructed because one did not know the intellectual underbelly of them, as it were. As a matter of fact most of Indian thinkers who have attained moksa were never undermined in their efforts by their intellectual abilities. What troubles Krishna even more is the other hidden dimension to Potter’s assumption, namely, that intellectual difficulties can be resolved once and for all so that a person is free to pursue moksa. However this seldom happens and most central intellectual issues continue to be debated down the ages. In addition most of the so-called intellectual problems arise because of the specific mental or speculative nature of philosophy itself and hence intellectual problems are both the name of the disease and the cure for it, so to speak.

Another effort to prove the same thesis as Potter’s is provided by Krishna Chandra Bhattacharyya’s works on the subject as freedom (Bhattacharyya 1983). According to Bhattacharyya philosophical

reflection is an essential ingredient in the attainment of moksa through sadhana or yoga: “Moksa is certainly non-conceptual, but only a conceptual reflection can make us aware of it as the ultimate and inmost possibility and reality of our being” (Krishna 1965, p. 43). Therefore Indian philosophy is integrally and positively related to moksa: “Philosophy, then, on this view, would be analogous to a theoretical discipline whose conceptually discovered realities are verified by a process of practical application which is traditionally known in India as sadhana” (Krishna 1965, pp. 43-44.). Krishna however feels that this notion is mistaken: “The possibilities opened up once by philosophic reflection are for all time available to the human awareness, and one does not even have to go through the process of philosophic reflection again to become aware of them. Once the possibility of moksa, for example, has been seized by the philosophic intellect, there is nothing more for it to do except to lapse into quietude. The only task that remains for each individual is to realize it in his or her own life. Philosophy cannot help in this process, and, in fact, once the awareness has permeated and been accepted by the culture, it ceases to have any function at all” (Krishna 1965, p. 45).

According to Krishna what also militates against the solution of the moksa problem is that it is not considered to be dynamic or evolutionary in character. Indians firmly believe that moksa is a one-time achievement which in principle can be attained in this life itself and that it is also not something which is progressive in nature. Moreover it is interesting that neither Bhattacharyya nor Potter is concerned with the issue of the nature of the relationship between the concept of moksa and the theories of the different schools of Indian philosophy.

The third conception of Indian philosophy which is of concern to Krishna is the view that Indian philosophy is philosophy as elsewhere in the world and that it has hardly any thing to do with moksa. This seems to be a fairly good assumption except that it has to reconcile itself with the explicit mention of moksa in almost all the philosophical traditions of India. It is indeed intriguing that none has bothered to examine as to how the specific materialist categories of the Nyaya-Vaisesika or the controversies between the various schools of Buddhism are all supposed to be intimately related

to moksa or nirvana. Krishna is of the opinion that this happened perhaps because no one with an interest in moksa ever went the materialist way.

Krishna explains the pervasiveness of this concept by the fact that moksa did not belong to the dominion of philosophy alone – it was as much the ideal in other walks of life such as poetry, literature, medicine, grammar and economics. Moreover the claim to moksa was always being made because it was considered to be the highest ideal and every discipline wanted to claim that respectability. It is therefore important, Krishna contends (and I feel that the nationalist project in Indian philosophy should recognize), that moksa is not only not the exclusive preserve of intellectual work or philosophy it is not even a concern for many systems of Indian philosophy and is a minor term in many other schools.

Scepticism of the received wisdom on Indian philosophy has also been one of the concerns of the materialist approach. This approach has been highlighted by Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya who has consistently argued his line through a prodigious set of analytical and historical works (e.g. Chattopadhyaya 1959, 1964, 1969, and 1976). The continuity of the classical systems down the ages right up to modern Indian thought without the daring to break free of the overall structures set in antiquity has been the reason for the poor state of philosophy in India (Chattopadhyaya 1964, pp. 1-2). This was also noted by Rajendra Prasad (Prasad 1965). The continuation of the caste system and the vice-like grip of the law of karma were the sociological fetters for such deadness in Indian philosophy. This is very different from Europe wherein thinkers succeeded one another, the latest one often giving radical alternatives to old ideas or proposing altogether new theories and conceptualizations. The hangover of ancient beliefs and the overriding ideas and systems “...explains the incomplete emancipation of our philosophical thought from all kinds of religious credulities, mythological imagination and even the belief in ritual practices” (Chattopadhyaya 1964, p. 6). This is again different from the development of Greek philosophy which had shown signs of throwing off the yoke of Equally worrisome is the near total lack of historicity of the philosophers and most of the written works. One knows next to nothing of the backgrounds, contexts and

motivations of the authors and many a times the names of the authors did not fit in historically with any age. This is troublesome especially for the historian of philosophy because of the vastness of the Indian sub-continent and the complexity of its ethnological composition. The materialist critique is also sceptic of the importance given to moksa in the course of Indian philosophy and provides a sociological analysis wherever moksa is revered: “...there is some exaggeration in thus indiscriminately attributing the ideal of moksa to all the Indian philosophers. For, in fact, the Lokayata laughed at it, the early Mimamsakas were indifferent to it and it was grafted on the Nyaya-Vaisesika not, at any rate, to enhance its philosophical consistency. Nevertheless, some of the important philosophical systems did advance this as the highest human ideal...this importance given to moksa in Indian philosophy, far from being any recognition of its real greatness, was perhaps the result of a backward and stagnant economy: the prospect of a greater real mastery of the world being denied, a large number of our philosophers sought refuge in the ideal of escaping it” (Chattopadhyaya 1964, p. 16).

Chattopadhyaya furthermore argues for a classification of the Indian philosophical systems on the idealism-materialism axis rather than the usual way of recounting the glories of the Vedas and the Upanisads before providing accounts of the nastika and astika philosophical schools (Chattopadhyaya 1964, pp. 101-106). This is so because right from the time of the Upanisads very clearly there is indication of materialism which was being, although recognized, constantly run down by the orthodox Indian philosophy which placed primacy on ideas. Materialism is often portrayed by the idealists as the secret knowledge of the devils or asuras. A very important feature of materialism was that nature or svabhava was the cause of everything. Sankara described svabhava as the natural power inherent in different things. In contrast therefore to accidentalism and chaos theory svabhava exhorts us to look for changes and transformations to the thing itself to which they belong. There are thus eternal natural laws which govern most of the world. This view of causality discouraged a belief in transmigration of souls, law of karma, and any thing to do with the supernatural. Svabhava thus formed the philosophy of the early materialists in Indian philosophy known as the Caravaka or Lokayata. On the basis of this