OUR SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

OUR SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

This document may also be downloaded from the

Department of Human Services web site at:

www.dhs.vic.gov.au

Unless indicated otherwise, this work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. The licence DOES NOT apply to any software, artistic works, images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and any Victorian Government departmental logos. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au It is a condition of this Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licence that you must give credit to the original author who is the State of Victoria. Authorised and published by the Victorian Government,

1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. ISBN 978-0-7311-6641-1 (print) ISBN 978-0-7311-6642-8 (on-line) March 2014 [2141112].

1. Minister’s foreword 4

2. Executive summary 6

Drivers for reform 6

A new vision for reform 7

Approach to reform 8

3. Development of this plan 11

3.1 Sector consultation 11

3.2 The views of children and young people 12

4. Victoria’s out-of-home care system 14

4.1 A history of reform 14

4.2 The current system 16

5. The case for reform 20

5.1 Identified challenges 20

5.2 ‘Performance’ of the system 21

5.3 The balance of investment 22

5.4 System integration 24

6. A new vision for reform 25

6.1 Reform strategy 25

7. Approach to reform 28

8. Longer-term reform deliverables 31

8.1 A new funding model 31

8.2 A new service delivery platform 31

9. Immediate reform actions 33

9.1 Improve the safety and wellbeing of children and young people in residential care 33 9.2 Tender the delivery of therapeutic, outcomes-focused, care and support services 34

9.3 Implement an outcomes monitoring framework 34

9.4 Develop a complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people 37

9.5 New governance arrangements 38

Improving processes and reducing the administrative burden 39 Improving health and education outcomes 39

Establishing local networks 40

9.6 Increase focus on stability and permanency 41

9.7 Explore professionalised in-home support 42

9.8 Provide additional support to reduce sexual exploitation 42

9.9 Improve leaving care support 43

9.10 Trial a new approach to kinship care 44

9.11 Better engage foster carers 45

Improving carer recruitment 45

Respecting and listening to foster carers 45

9.12 New approaches to commissioning 45

10. Next steps 47

11. References 48

Appendix A – Statement of principles 49

Government, service providers and the community have a responsibility to do all we can to make sure the care vulnerable children and young people receive sets them on the path to a good life. Currently across Victoria, more than 6,400 children and young people are living in out-of-home care. They are being looked after by thousands of foster, kinship,

permanent and residential carers – and many other support staff – who work tirelessly to make sure that these children and young people live happy, safe and rewarding lives.

Effectively caring for and improving the life outcomes of our most vulnerable and disadvantaged children and young people is an enormous challenge. At the heart of the challenge lies the fact that no government-funded or delivered system can ever truly replace a good parent in a child’s life. This reality must drive our efforts to ensure we do a better job in supporting families to provide safe, stable, nurturing homes for all children and young people. Where families fail in looking after children, safety, stability and nurturing must be provided through our alternative care arrangements. Every year, the number of young Victorians who need out-of-home care is growing, and both government and the community are under increasing pressure to deliver the financial and human resources required to keep pace. Despite the good outcomes achieved for many children, multiple reports and inquiries here, inter-state and overseas have catalogued the challenges facing out-of-home care systems and warned the structure is under significant stress. The traumatic impact of abuse and neglect on children and young people is significant. We know failure to provide stable, supportive care can further magnify this impact.

This Government is responding to the range of challenges confronting the broad child protection system. In May 2012, we published Victoria’s Vulnerable Children – Our Shared Responsibility Directions Paper and allocated $336 million over four years from the 2012–13 Budget. That funding, together with allocations made in the 2011–12 and 2013–14 Budgets has taken the Victorian Government’s additional investment in vulnerable children and families to more than $650 million over the past three Budgets.

Through the complementary Victoria’s Vulnerable Children – Our Shared Responsibility Strategy 2013–2022, released in May 2013, the Victorian Government has formally accepted a shared responsibility for improving outcomes for vulnerable children. This is underpinned by our commitment to work better across portfolios that have responsibility for the health, social and economic determinants of vulnerability. In December 2013, the Government released a baseline performance data report as an important first step to understanding the challenges faced by vulnerable children and young people. This sets the baseline from which annual performance reports will measure our progress in reducing vulnerability and improving the lives of the most vulnerable Victorians.

This plan is a statement of our intent to fundamentally reform the way the out-of-home care system operates in order to drive better personal, social and economic outcomes for children and young people in care. The proposed reforms align with our new model for integrated human service delivery – Services Connect – that is driving a more integrated and holistic approach to working with vulnerable Victorians.

It also reflects the importance of a collaborative approach to reform between government, service providers, clients and other stakeholders – as recommended in the report Service Sector Reform: A roadmap for community and human services reform.

Through these reforms we intend to move our historical program-based funding for out-of-home care to a system that is more focused on the client and the outcomes we aspire to. To achieve this, we need a system that more closely integrates family support, preservation and reunification services with those that provide out-of-home care; a system that provides incentives for positive outcomes and is delivered from a local area-based platform. We want to provide the flexibility that is needed to encourage innovation in how best to meet the needs of children and young people in care, their families and their carers.

We have consulted with service providers, the Commission for Children and Young People and other stakeholders to define this plan and will continue this collaborative approach throughout implementation. We recognise success depends on the support and input of service providers and experts as well as children and young people themselves.

To begin this process, the Victorian Government will undertake a tender process during 2014 for the delivery of a more holistic, flexible and therapeutic care and support service for children in out-of-home care and their families. This new approach will focus on the outcomes sought – as opposed to service types, inputs or outputs. It will seek to create a service response which focuses on the overarching goal for each child and young person in a placement – whether this is successful reunification with parents; placement in a stable, permanent care arrangement; or transition to independence.

Other immediate priorities to strengthen our system are to:

> Realise legislative and practice reforms to help provide permanency and stability for children. > Investigate opportunities to better support and grow our vital foster carer workforce. > Increase the role of the non-government sector in assessing and supporting kinship care

arrangements.

> Establish a practical approach to monitoring the outcomes being achieved for children and young people in care. Based on this information, a process for reporting on the wellbeing of children and young people in the care of each service provider will also be established. > Commence immediate actions to improve the safety and wellbeing of children and young

people in residential care.

> Develop a complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care. > Explore innovative approaches to commissioning, targeted at preventing entry to care,

supporting transition from residential care and improving leaving care supports.

> Establish a more collaborative and effective approach to governance – and through this – identify and act on opportunities for practical system improvements.

The specification and implementation of change will take time, but it is enormously important. This holistic approach to reform will benefit both children and the sector.

Importantly, the implementation of the plan will be supported by a funding package totalling $128 million over the next four years.

I look forward to working with service providers, carers and children and young people in care to make this plan a reality.

The Hon. Mary Wooldridge MP

2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This plan articulates a reform strategy for out-of-home care that will deliver a more integrated, client-centred and outcomes-focused service system. It builds on Victoria’s leadership in out-of-home care and human services reform to present both immediate and longer-term actions to achieve three overarching goals:

> Improved outcomes – improved personal, economic and social outcomes for children and young people in out-of-home care.

> Reduced demand – slow the growth in the number of children and young people being placed in out-of-home care over the long-term.

> Sustainable delivery – create the foundation for a more sustainable, efficient and effective out-of-home care system.

Drivers for reform

The Victorian Government is committed to driving improvement across the delivery of human

services. The Government’s recent policy statement Services Connect: Better services for Victorians

in need demonstrates the need for a more integrated, holistic, effective, efficient and sustainable human services system. Specifically, it highlights the need for more integrated service delivery, a stronger focus on outcomes and supporting service provider innovation through a more flexible approach to funding.

The evidence for these reform directions is clear in the Service Sector Reform: a roadmap for

community and human services reform. Recent reviews and reports also highlight the overall structure of the statutory child protection and out-of-home system is under significant stress and that the need for improvement and reform is pressing. Current challenges facing the system range from rising demand to a fragmented system that is not designed to enable the innovation and outcomes we aspire to achieve.

In January 2011, the Victorian Government initiated the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry to investigate systemic problems of Victoria’s child protection system. The final report, tabled in Parliament in February 2012, found:

‘there are major and unacceptable shortcomings in the quality of care and outcomes for children and young people placed, as a result of statutory intervention, in Victoria’s out-of-home care system. Further, the Inquiry considers there are a number of long-term factors impacting on the outcomes and sustainability of the current approach to providing accommodation and support services to children in out-of-home care. Major reform of the policy framework, service provision and funding arrangements for Victoria’s out-of-home

care system is therefore urgently required.’1

The Victorian Government is committed to reform of the out-of-home care system. In May 2012,

the Victorian Government published Victoria’s Vulnerable Children – Our Shared Responsibility

Directions Paper and announced a program of investment to support reform. That funding, together with allocations made in the 2011–12 and 2013–14 Budgets has taken the Victorian Government’s additional investment in vulnerable children and families to more than $650 million over the past three Budgets.

This out-of-home care plan is part of a broader suite of initiatives to improve outcomes for

vulnerable children. The Victoria’s Vulnerable Children – Our Shared Responsibility Strategy

2013–2022 (Vulnerable Children’s Strategy), released in May 2013, includes three goals focused on reducing child vulnerability. As of March 2014, 63 actions have been implemented and a further 40 are underway. This plan is a key mechanism to achieve goal three within the Vulnerable Children’s Strategy.

1 Department of Premier and Cabinet 2012. Report of the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry Department of Premier and Cabinet, Melbourne, p.233.

Goals and achievements

Goal 1: Prevent abuse and neglect Reforms and achievements include:

> Additional 1,000 early childhood intervention service places each year to support children with a disability or developmental delay from birth until school age.

> A new Maternal and Child Health Memorandum of Understanding is now in place with the DEECD and the Municipal Association of Victoria for 2012–2015.

> Expanded the Enhanced Maternal and Child Health Service.

> Reform of Student Support Services to help strengthen the early identification of children and young people at risk.

> New student online case system to support service delivery to vulnerable students.

> Established national Foundation to Prevent Violence Against Women and their Children. Goal 2: Act earlier when children are vulnerable

Reforms and achievements include:

> Children, Youth and Families Amendment Bill 2013 to make the court experience more child-friendly.

> Provide more than 1,000 additional places over four years in voluntary Men’s Behaviour Change Programs.

> Establish two new demonstration sites for the Adolescent Family Violence initiative.

> New operating model for statutory child protection.

> An additional 89 front-line child protection practitioners.

> Victoria Police established Taskforce Astraea to tackle child exploitation on the internet.

> Victoria Police has established 27 Family Violence Teams and 27 Sex Office and Child Abuse Investigation Teams across the state.

Goal 3: Improve outcomes for children in statutory care Reforms and initiatives include:

> Permanent Care and Stability Project – to increase rates of timeliness of permanent care arrangements.

> Zero fee training places for young people leaving care.

> Springboard program to assist young people leaving care to access education and employment.

> Pilot to assist in implementing Aboriginal guardianship in Victoria.

> Release of the five year plan for out-of-home care.

> A more child-friendly legal system and a new children’s court in Broadmeadows; and state-wide roll-out of new model conferences.

> 140 new therapeutic residential and foster care places.

> Comprehensive educational and health assessments and learning mentors for children in out-of-home care.

The Victorian Government has also developed this plan in consultation with the sector and key stakeholders to define a clear reform strategy for the next five years.

A new vision for reform

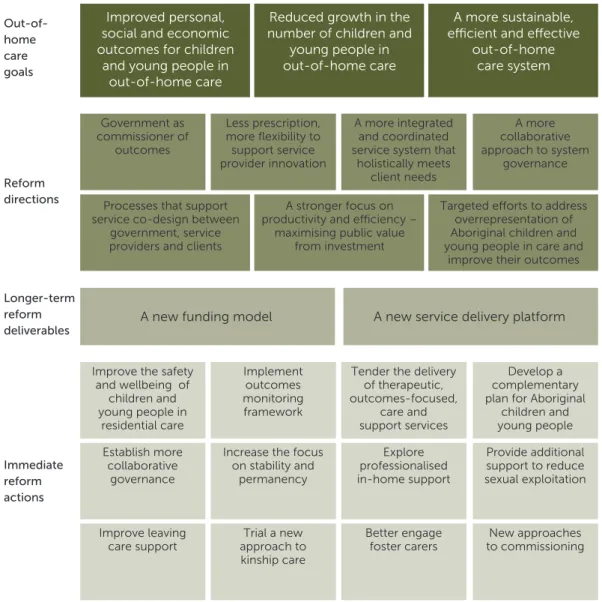

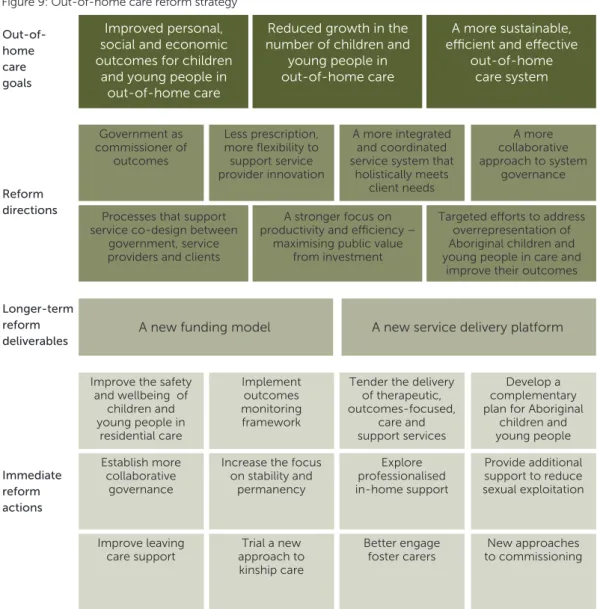

More fundamental reform is required to reset how out-of-home care is funded and delivered across Victoria. Simply tweaking the current system by further increasing funding levels or establishing new stand-alone programs will not lead to the sustainable, systemic improvement we aspire to achieve. This plan recognises that some reform will take time to be achieved and that we must balance our effort between longer-term enablers and immediate opportunities to achieve the best results. The reform strategy is summarised in Figure 1 on the following page.

Figure 1: Out-of-home care reform strategy

The reform strategy is informed by the multiple reviews and policy statements, including the Report of the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children’s Inquiry, which have shown there is a clear need to further improve outcomes being achieved for children and young people in out-of-home care. It also recognises there is a pressing need to ensure that the out-of-home care system and other support services that children, young people and their families rely on are structured and function as efficiently and effectively as possible.

Approach to reform

The journey that begins with the release of this plan will not be complete for several years – and is in reality an ongoing process. The Victorian Government is committed to working collaboratively with non-government organisations and other stakeholders to deliver on the whole-of-government commitment to improving outcomes for children and young people in out-of-home care, as articulated in the Vulnerable Children’s Strategy and in this plan.

The reform process this plan signals will be a complex one. It is essential that it proceeds cautiously – but not so cautiously that we unnecessarily delay the opportunity for significant reform. Figure 2 summarises the process and timing for development and delivery of this reform plan.

Improved personal, social and economic outcomes for children

and young people in out-of-home care

Government as commissioner of

outcomes

A more integrated and coordinated service system that

holistically meets client needs

A more collaborative approach to system

governance Processes that support

service co-design between government, service providers and clients

A stronger focus on productivity and efficiency –

maximising public value from investment

Targeted efforts to address overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people in care and

improve their outcomes

Out-of-home care goals

A new funding model A new service delivery platform Longer-term

reform deliverables Reform directions

Reduced growth in the number of children and

young people in out-of-home care

A more sustainable, efficient and effective

out-of-home care system

Less prescription, more flexibility to support service provider innovation

Improve the safety and wellbeing of

children and young people in

residential care

Tender the delivery of therapeutic, outcomes-focused, care and support services Develop a complementary plan for Aboriginal

children and young people Immediate reform actions Implement outcomes monitoring framework Establish more collaborative governance Explore professionalised in-home support Provide additional support to reduce sexual exploitation Increase the focus

on stability and permanency Improve leaving care support Better engage foster carers New approaches to commissioning Trial a new

approach to kinship care

Figur

e 2: Out-o

f-home car

e r

ef

orm appr

oach

2

0

14

2

0

15

2

0

16

A new funding model A new service delivery platform

Tender Delivery of a new out-of-home care system

The

reform advisory group

provides advice on future reform directions linked to the

Community Sector Reform Council

Tender for the delivery of therapeutic, outcomes-focused, care and support services Taskforce 1,000 – Improving outcomes for Aboriginal children and young people in care

Ongoing communication and consultation

with sector, children and young people

Release of implementation blueprint

Roll-out

Implement outcomes monitoring framework for children and young people in care Complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people Other immediate system improvements Phase one roll-out Roll-out to targeted (or trial) areas to test approach

Longer-term reform opportunities

Immediate reform

opportunities Governance Time

2014 work on options papers and immediate opportunities informs the development of longer-term reform strategies.

Achieving the longer-term reform directions needed will require us to reconsider the types of services government funds; the mix of these services; the funding models and mechanisms we use; who is funded to deliver the services; and the spread of services across the state. The key longer-term deliverables are:

> A new funding model that supports more innovative services and promotes a stronger focus on the outcomes we achieve for children and young people.

> A process to establish a more integrated service delivery platform that better supports placement prevention and reunification, and responds better to the needs of children and young people in or exiting care.

These two deliverables combine to support achievement of the overarching objectives of this plan to improve outcomes, reduce demand and enhance sustainability of the system. Importantly, they will build placement capacity across the state by unlocking current resources and creating much needed flexibility to support new approaches to how we find the safest, most stable and nurturing care arrangements for vulnerable children and young people.

These longer-term deliverables will be informed by further consultation and a number of immediate reform actions. Three immediate reform actions identified include:

> A tender process for the allocation of new funding to trial new approaches to therapeutic care across the state. This new approach will place a more explicit focus on outcomes to be achieved for children in care and service providers will be encouraged to innovate to provide a more tailored service response for each child in their care. They will also be required to provide support to the child, their family and their carer to achieve each child’s case plan goals. > Trial of a new outcomes framework for all children and young people in care. Utilising an

appropriate information management platform, the Victorian Government will establish a state-wide planning, assessment and outcomes-measurement system for use by all government-funded out-of-home care providers. We will regularly report on the results of this process. We will also report regularly on a number of additional measures that will provide a picture of overall agency performance.

> Development of a complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people that identifies specific actions to address the over representation of Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care and improve outcomes.

To support this work the Victorian Government will establish a Reform Advisory Group which will be linked with the Community Sector Reform Council. This group will provide technical advice to the Department of Human Services (department) on the implementation of this plan and support appropriate consultative and information sharing processes to ensure that all service providers remain informed and engaged in the reform process.

Informed by this advice and the experience of the immediate reform actions, the department will provide an options paper to the Victorian Government at the end of 2014 on the proposed direction for the long-term reform deliverables.

3.1 Sector consultation

In the spirit of improved collaboration and service co-design between government, service providers and clients, this plan has been developed with considerable input from out-of-home care service providers.

During 2013, a series of workshops were held to consider how the out-of-home care system could be refined to achieve improved outcomes for children and young people in care. All organisations funded to deliver out-of-home care services in Victoria were invited to attend. The Department of Human Services, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and the Commission for Children and Young People also participated. At the conclusion of these sessions, a group of service providers presented a formal submission to the Victorian Government to inform the development of this plan.2

This submission outlined sector challenges and opportunities, and offered a series of immediate, medium and long-term actions for consideration. Broadly, it called for:

> Measurable outcomes that respond to the needs and promote the wellbeing and development of children and young people in out-of-home care.

> More flexible, place-based services that can be tailored to the needs of children and young people.

> Fair and adequate funding arrangements.

> Workforce arrangements that support improved quality and responsiveness. > Inclusive and representative area-based governance arrangements.

Consultations concerning the specific challenges confronting Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care were also held in mid to late 2013, facilitated by the Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People, Mr Andrew Jackomos. These consultations provided an opportunity for Aboriginal community controlled organisations and other providers to develop a submission for this plan and map out a process for further contribution to the complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people.3

The submission, provided in November 2013, highlighted concerns with the persistent and growing overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people in care, and the out-of-home care system’s failure to ensure these children and young people remain connected with their families, community and culture. Concerns with poor outcomes and high rates of involvement with the youth justice system were also highlighted. The submission made a clear link with this overrepresentation and Australia’s history of dispossession of Aboriginal people and historical child removal practices.

2 Anglicare Victoria, Berry Street, EW Tipping, Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare, MacKillop Family Services, Salvation Army, Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, Wesley Mission Victoria 2013. Five Year Plan for Out of Home Care Submission from Victorian out of home care Community Service Organisations. The full text of that submission is available at:

www.cfecfw.asn.au/sites/www.cfecfw.asn.au/files/5_Year_Plan_Submission.pdf.

3 A joint submission from Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations and Community Service Organisations 2013. Koorie Kids: Growing Strong in their Culture. The full text of that submission is available at: www.ccyp.vic.gov.au/downloads/ submissions/submission-koorie-kids-growing-strong-in-their-culture-nov13.pdf

The submission recommended seven priorities that the complementary plan for Aboriginal children should consider:

> Priority One: develop an Aboriginal child and youth-focused cultural outcomes framework for out-of-home care, from entry to exit, which embeds Aboriginal children’s rights around self-determination.

> Priority Two: create a comprehensive approach to address the cultural needs of Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care.

> Priority Three: build the capacity of Aboriginal families and communities to care for their children.

> Priority Four: place all Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care under the care, authority and case contracting/management of an Aboriginal community controlled organisation.

> Priority Five: extend and enhance the coverage of the Aboriginal child welfare sector so Aboriginal children and young people can access early intervention, home-based, residential and permanent care within the broader suite of out-of-home care services in the area they live. > Priority Six: grow and better support Aboriginal carers.

> Priority Seven: ensure compliance to meet the intent of legislative requirements in the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 as it relates to Aboriginal children and young people.

The process for developing the complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people is outlined later in this plan.

3.2 The views of children and young people

The primary aim of this plan is to drive improvements for children and young people in out-of-home care. Every child and young person has the right to participate in the decisions that will impact on their lives. As discussed throughout this plan, one of our system’s main failings is that we do not systematically collect information about how well children and young people in care are faring – and in particular information from children and young people themselves.

This plan proposes a means for much stronger, systematic engagement with children and young people in care concerning their experiences. We will collate information about their education, health and social outcomes, which will further inform policy and service provision into the future. While we have not historically had a systemic approach to ensuring the voices of children and young people in care are adequately heard, our new approach to gathering outcomes information will address this.

The CREATE Foundation’s Report Card 20134 was based on a national survey of more than 1,000

children and young people in care (162 from Victoria). It was designed to provide a benchmark for how the system is faring in 2013 from the perspective of these children and young people. It dealt with outcomes across all of the Looking After Children life domains (the framework used by all Victorian out-of-home care providers) and the National Standards for Out-of-Home Care. One of the issues the survey explored were the factors of ‘good’ and ‘not good’ placements – as described by children and young people in care. The following finding was of note: ‘without doubt, the experience of a warm, caring and supportive relationship defined the good placements.’5

4 McDowall, J.J 2013. Experiencing out-of-home care in Australia: The views of children and young people (CREATE Report Card 2013), Sydney: CREATE Foundation.

5 McDowall, J.J 2013. Experiencing out-of-home care in Australia: The views of children and young people (CREATE Report Card 2013), Sydney: CREATE Foundation, p.34.

This relationship provided the foundation for other important positive outcomes in the areas of education, social and family connectedness, health and so on. This is not a surprising finding, but it underscores the vital role that foster, kinship or residential carers – and others – play in driving better outcomes for children and young people. It also underscores the importance of knowing you are living in a stable, permanent home. Providing this crucial relationship in the life of all children and young people in care is at the heart of our long-term vision for out-of-home care in Victoria. The Report Card provides a comprehensive picture of the things that are important to children and young people. It echoes the findings of the survey and focus groups undertaken by the CREATE Foundation to support the work of the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry (Cummins Inquiry). That research identified a number of issues of importance to children and young people in care, highlighting:

> The importance of having someone within their care environment with whom they have an emotional connection.

> The importance of participating in decisions that affect them. > The importance of feeling and being safe in their placement.

The CREATE report undertaken for the Cummins Inquiry identified a significant difference in feedback received from children and young people placed in home-based care compared with those who live in residential care. While the majority of children in home-based care spoke positively about their carers and generally being happy in their placements, those in residential care expressed real concerns regarding safety and with the negative influence and impact of some of the young people they were placed with.

Negative peer influence is an issue all young people and their families will need to deal with from time to time. For children and young people in out-of-home care, however, the impact of negative influences can be more significant. This is due in part to the fact that for some children and young people their own experience of abuse and neglect makes them highly vulnerable to external influences and often contributes to a range of extreme behaviour. It is further magnified by the absence of strong parental figures in their lives, setting the clear values and boundaries all children and young people need.

The young people consulted in the CREATE Foundation study emphasised the importance of assessing and matching young people before they are placed within a particular residential care unit. Numerous reviews have identified that in some cases appropriate matching of young people to placements had not been possible. This was due primarily to the system’s inability to keep pace with the rising demand for placements – particularly in home-based foster care.

This feedback is important and relevant to the aspirations of this plan. Improving the system’s capacity to match children and young people with appropriate placements is a major issue the plan must address. To date, our system has been responding to this issue via the establishment of ‘contingency’ units – short-term residential care arrangements, which are not recurrently funded, and which offer no certainty or stability to the child in care or the service provider. These arrangements are not ideal for supporting the development of a strong emotional connection with a carer, which children and young people have identified as central to a good placement.

Significant efforts are already underway to reduce the use of contingency placements. Later in this plan we outline our proposed approach to increasing placement capacity in order to maximise opportunities for the development of the stable and nurturing relationships children and young people have identified as essential.

4.1 A history of reform

Victoria has a long history of leadership in out-of-home care. The shape of out-of-home care has changed considerably in recent decades, and will inevitably continue to change. The evolution of Victoria’s out-of-home care system is illustrated in Figure 3 and detailed below.

Figure 3: Victoria’s history of reform

Pre-1950, nearly all children in care lived in residential care. Many of these were living in large facilities operated by non-government organisations or one of the large state-run institutions of Allambie, Turana, Baltara or Winlaton. From the 1950s, more children and young people started moving into small family group home arrangements. Family group homes were typical suburban houses where a married couple would provide care for up to four children, in addition to any children of their own. In most of these cases, the husband would undertake paid employment outside the home, while his partner provided full-time care for the children.

This move away from large institutions towards more normal home-like environments reflected the growing awareness that such facilities provided far from ideal homes for children and young people. Evidence of abuse and neglect of children in care within these institutions has now clearly emerged, and the ramifications of this treatment still impacts the lives of many of these now adult care leavers – a fact acknowledged by the Victorian and other governments through their respective apologies to people abused and neglected in their care.

During the 1970s the closure of large institutions created further momentum for home-based care arrangements. Non-government organisations were supported to move away from congregate care towards family group home arrangements and an expanded foster care program.

By the 1980s, around half of all children in care were living in some form of residential care compared to 85 per cent in 1960. Most of these children were aged 10–18 years, with younger children more often placed in foster care.

Mor

e client-f

ocused models o

f car

e

Pre-1950 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Current

Charitable organisations

and government operate a mix

of orphanages and reformatory schools. Some early home-based care models emerge at different times, however large-scale institutional care dominates. Early moves towards family group homes and foster care. Large-scale residential care still dominates. Family group homes and foster care gather more momentum. 85 per cent of children in residential

care.

More than 50 per cent of children and young people still in

some form of residential

care – large and small-scale.

Last of the state-run residential care institutions closes. Home-based care and smaller residential care services expand. Kinship care emerges. Increased focus on therapeutic care responses. Kinship care continues to grow. Home-based care now dominates Kinship care the predominant care type. Therapeutic care responses expanding. Residential care less than 10 per cent of total system.

Future focus:

Continued support for kinship care.

Foster care continues to play

a key role. Therapeutic care responses expand. Stronger focus on outcomes and

tailored care responses. Greater emphasis on timely stability planning. System reform to reduce demand and improve outcomes for all children. Increase in home-based care Increased focus on child development Increased focus on therapeutic care, protection and support

4. VICTORIA’S OUT-OF-HOME

CARE SYSTEM

The last large state-run residential institution – Allambie – was closed in 1990. In the decade that followed, the range of home-based care options expanded further and the move towards kinship care gathered pace as government set a clear policy preference for children to be cared for within their existing family or social networks wherever appropriate. Changes in industrial arrangements and the increasingly complex behaviours of children and young people placed in care also saw a shift away from family group homes towards rostered residential care services, where a rotating shift of staff oversee day-to-day care. Today no family group homes remain, and all children in residential care are cared for by a rostered staff team.

The recent focus of reform has been on investment in therapeutic care responses. This has been informed by our growing understanding of the impact of neglect, abuse and trauma on a child’s developing brain and type of care responses this requires. Services such as Take Two, therapeutic residential care and therapeutic foster care have provided many volunteer carers and staff with a much deeper understanding of how to care appropriately for children placed with them.

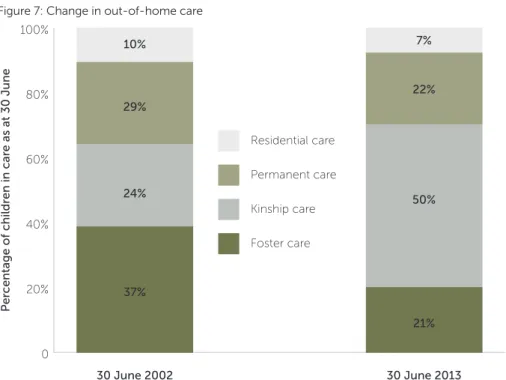

This evolution of out-of-home care has led to a system that is shaped very differently to that of the 1950s. Currently, only about seven per cent of children and young people reside in residential care; 50 per cent in kinship care; 21 per cent in foster care; and 22 per cent in permanent care (often with kin or a previous foster carer).

This structure reflects the Victorian Government’s preferred ‘hierarchy of responses’ for children in out-of-home care. Wherever possible, the preferred option is to prevent children and young people entering care in the first place. Many families experiencing difficulties are supported day-by-day to provide safe, stable, nurturing care for their own children. Victoria’s relatively low out-of-home care placement rates reflect the fact that placement in care is seen as a last resort, a step taken only when the risk of harm to the child requires it.

Where families fail to look after their children, however, alternative care arrangements are required and must provide a safe, stable and nurturing home for these children. Informed by an assessment of each child or young person’s best interests, our preferred forms of placement are:6

1. Kinship care – where care is provided by a relative or existing member of the child or young

person’s social network. Kinship care has the benefit of both maintaining a child within their family/network and minimising any unnecessary intrusion in family life by government.

2. Foster care – where care is provided by a volunteer carer in their own home – supported by a

community service organisation.

3. Residential care – where care is provided in small, community-based houses staffed by

rostered employees.

6 Wherever possible children and young people who are unable to return to parental care will be placed on permanent care orders. These orders grant guardianship of the child to a permanent carer – who is most commonly a family member or a foster carer who had been caring for the child.

4.2 The current system

Since 2002, the number of children and young people in out-of-home care has grown by 5.3 per cent per annum (Figure 4).7 This far exceeds the growth in Victoria’s 0–17 years population, which

has increased by only 0.5 per cent per annum. For Aboriginal children and young people in care the rate of growth has been even higher – 9.5 per cent per annum against a total Aboriginal 0–17 years growth rate of 2.2 per cent per annum.8

Figure 4: Growth in the out-of-home care population

This rate of growth is significant, but compared with other Australian states and territories it is relatively modest. During the period 2002 to 2013, the out-of-home care populations in New South Wales and Queensland grew by 116 per cent and 150 per cent respectively, compared to Victoria’s growth of 77 per cent.9

Victoria’s placement rate is the lowest in the country at 5.0 per thousand children and young people aged 0–17 years. This is below the Australian rate of 7.7 per thousand. New South Wales’ rate of 10.5 is more than double the Victorian rate, as is the Northern Territory’s rate of 11.8 per thousand.

7 Department of Human Services data. 8 Department of Human Services data.

Number o

f childr

en in out-o

f-home car

e a

t 30 June

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Aboriginal children in Out-of-home care at 30 June each year

Non Aboriginal children in Out-of-home care (includes unknown) at 30 June each year All children in Out-of-home care at 30 June each year

If out-of-home care population had grown at the 0–17 population growth rate 0

1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000

9 Department of Human Services Data – drawn from Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision 2013, Report on Government Services 2014, Productivity Commission, Canberra.

Whilst comparatively contained, a key contributor to the growth in the number of children and young people in care in Victoria has been the increasing length of care placements.10 The

proportion of children staying in (non-permanent) care for five years or more has almost doubled over the last decade.11 This fact demands attention, both to ensure opportunities to reunite

children with parents are not being lost and to ensure more timely placement of children in stable, permanent care arrangements where appropriate. There is an urgent need to do a better job in making timely decisions about the long-term care of children, where there is minimal chance that the factors that led to their removal from home will change.

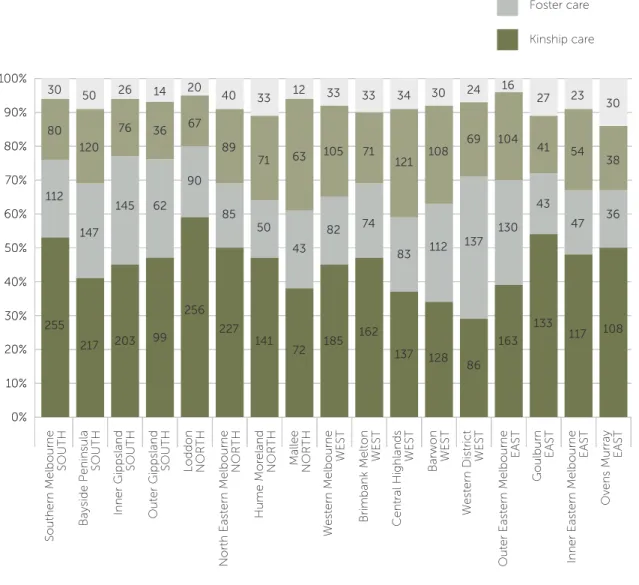

Within Victoria there are significant variations in placement rates and placement types between areas (Figure 5 and Figure 6).12 In part this reflects differences in levels of socio-economic

disadvantage but is also likely influenced by service availability, variations in practice and service effectiveness on the part of both government departments and service providers.

Figure 5: Placement rate by area

10 Department of Premier and Cabinet 2012. Report of the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry, Department of Premier and Cabinet, Melbourne.

11 Department of Premier and Cabinet 2012. Report of the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry, Department of Premier and Cabinet, Melbourne. pp. 243–244.

12 Department of Human Services data (Note that ‘area’ relates to the area of the agency or DHS outlet providing out-of-home care services).

Ra

te o

f childr

en in out-o

f-home car

e per 1,

000 in the popula

tion

Ra

te o

f Aboriginal childr

en in out-o

f-home car

e per 1,

000 in the popula

tion Outer Gippsland SOUTH Inner Gippsland SOUTH W estern District WEST Central Highlands WEST Mallee NORTH Loddon NORTH

Ovens Murray EAST Goulburn EAST Barwon WEST Brimbank Melton WEST

Outer Eastern Melbourne

EAST Hume Mor eland NORTH Southern Melbourne SOUTH

North Eastern Melbourne

NORTH W estern Melbourne WEST Bayside P eninsula SOUTH

Inner Eastern Melbourne

EAST

Rate of children in out-of-home care per 1,000 children in the population (aged 0–17 years)

Rate of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care per 1,000 Aboriginal children in the population (aged 0–17 years)

71.0

Average rate of children in out-of-home care statewide

0 23 46 69 92 115 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50

Average rate of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care per 1,000 Aboriginal children

11.3 114.1 11.2 56.4 9.2 75.4 9.0 53.6 8.7 85.1 8.4 40.8 7.7 51.3 6.8 81.2 6.4 53.1 4.6 78.3 4.5 67.4 4.1 27.9 4.0 75.9 3.9 40.8 3.9 36.5 3.2 50.7 2.0

The situation for Victorian Aboriginal children and young people is particularly concerning, as illustrated in Figure 5. The average placement rate of 59 per thousand far exceeds the non-Aboriginal rate of five per thousand, and is slightly higher than the Australian average for Aboriginal children (56.9). This is clearly an issue that requires significant focus as this plan, and the complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people, is implemented.

Figure 6: Placement types by area

The care profile of out-of-home care has changed significantly over the past decade, illustrated in Figure 7 below.13 In particular, there has been a distinct shift away from foster care towards kinship

care. This reflects a deliberate policy of placing children and young people in kinship care wherever it is possible and in their best interests to do so, in order to maintain family relationships and

connections. It also reflects the ongoing challenge of attracting and retaining volunteer foster carers.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Residential care Permanent care Kinship care Foster care 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Outer Gippsland SOUTH 99 62 36 14 Inner Gippsland SOUTH 203 145 76 26 W estern District WEST 86 137 69 24 Central Highlands WEST 137 83 121 34 Mallee NORTH 72 43 63 12 Loddon NORTH 256 90 67 20 Ovens Murray EAST 108 36 38 30 Goulburn EAST 133 43 41 27 Barwon WEST 128 112 108 30 Brimbank Melton WEST 162 74 71 33

Outer Eastern Melbourne

EAST 163 130 104 16 Hume Mor eland NORTH 141 50 71 33 Southern Melbourne SOUTH 255 112 80 30

North Eastern Melbourne

NORTH 227 85 89 40 W estern Melbourne WEST 185 82 105 33 Bayside P eninsula SOUTH 217 147 120 50

Inner Eastern Melbourne

EAST

117 47 54 23

Figure 7: Change in out-of-home care

The shift towards kinship care is generally positive for the children, young people and families concerned. However, it does mean an increased role for government as government-employed child protection practitioners are responsible for the case management and supervision of the majority of kinship care placements (around 2,500 compared to the 750 placements supported by non-government organisations).14

One of the issues that this plan will need to tackle is how we create a stronger role for the non-government sector in providing support for children in kinship care and their carers. The assessment and support of out-of-home carers and children in care are core skills of the non-government sector and future reforms should acknowledge and build on this expertise.

Figure 7 also illustrates that there has been a considerable reduction in the proportion (though not the number) of children and young people who are in permanent care placements with a secure and stable caregiver. Given the importance of stable care arrangements to a child or young person’s healthy development, there is a clear need for a much stronger focus on timely planning to improve permanency and stability through more permanent care placements.

30 June 2002 30 June 2013

0 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

37% 24% 29% 10%

21% 50% 22% 7%

Residential care Permanent care Kinship care Foster care

Per

centage o

f childr

en in car

e as a

t 30 June

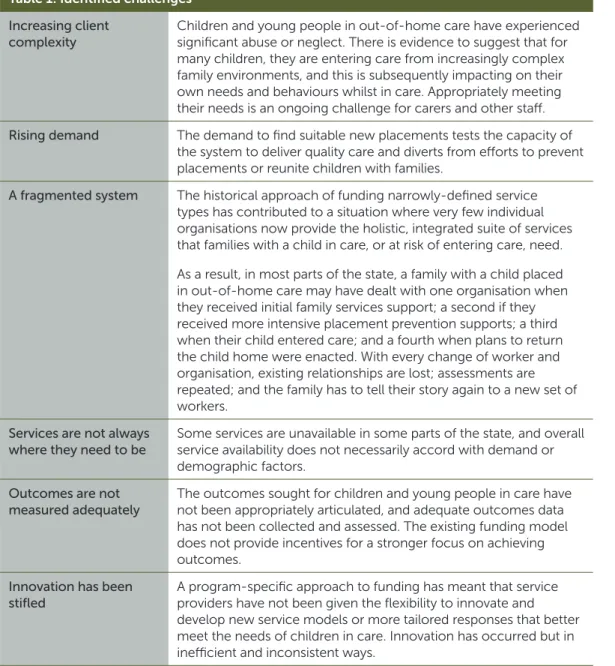

5.1 Identified challenges

Reviews and reports over the past decade have demonstrated a number of challenges for out-of-home care.

Table 1: Identified challenges

Increasing client complexity

Children and young people in out-of-home care have experienced significant abuse or neglect. There is evidence to suggest that for many children, they are entering care from increasingly complex family environments, and this is subsequently impacting on their own needs and behaviours whilst in care. Appropriately meeting their needs is an ongoing challenge for carers and other staff. Rising demand The demand to find suitable new placements tests the capacity of

the system to deliver quality care and diverts from efforts to prevent placements or reunite children with families.

A fragmented system The historical approach of funding narrowly-defined service types has contributed to a situation where very few individual organisations now provide the holistic, integrated suite of services that families with a child in care, or at risk of entering care, need. As a result, in most parts of the state, a family with a child placed in out-of-home care may have dealt with one organisation when they received initial family services support; a second if they received more intensive placement prevention supports; a third when their child entered care; and a fourth when plans to return the child home were enacted. With every change of worker and organisation, existing relationships are lost; assessments are repeated; and the family has to tell their story again to a new set of workers.

Services are not always where they need to be

Some services are unavailable in some parts of the state, and overall service availability does not necessarily accord with demand or demographic factors.

Outcomes are not measured adequately

The outcomes sought for children and young people in care have not been appropriately articulated, and adequate outcomes data has not been collected and assessed. The existing funding model does not provide incentives for a stronger focus on achieving outcomes.

Innovation has been stifled

A program-specific approach to funding has meant that service providers have not been given the flexibility to innovate and develop new service models or more tailored responses that better meet the needs of children in care. Innovation has occurred but in inefficient and inconsistent ways.

Performance is variable Every day, the lives of thousands of children and young people in out-of-home care are improved by the efforts of the foster, kinship, permanent and residential carers who look after them. However, we know that we can and need to do better in some areas. Statutory obligations around timely stability planning or development of cultural support plans for Aboriginal children in care have sometimes not been met. The approach to governance – and the establishment of effective ways to identify and resolve issues that affect service effectiveness – has been haphazard. In the area of placement provision, some service providers have consistently failed to provide the number of placements they are funded for, and the department’s approach to addressing poor performance has been inconsistent. As a result, there are some service providers who, over the course of a year, fall well short of delivering on their contractual obligations. Numerous factors have contributed to this scenario – chief among which is the ongoing challenge of attracting and retaining volunteer foster carers. However, the resultant mismatch between contracted targets and actual performance is unsustainable and needs to be addressed. Performance of placement prevention, reunification and leaving care support services has also been variable, with some of these services unavailable in some parts of the state. Timely supports are needed to prevent children entering care; to enable their safe return home; or to ensure a successful transition to independence. Training and keeping

staff is a challenge

There has been significant workforce capacity and retention issues both within and outside of government. This concerns both the volunteer and paid workforce.

The need to address these challenges is at the core of the reform directions and approach articulated in this plan.

5.2 ‘Performance’ of the system

Our ability to meaningfully assess the performance of the system has been limited by a lack of readily available outcomes data concerning children in care. Given this lack of data, our analysis of performance in this section is, by necessity, focused on the much narrower aspects of service availability and continuum, and provider performance against funded placement targets.

There are significant variations in the types of services available across different areas and in provider performance against funded targets. In home-based care, some service providers receive funding to care for more than 250 children while others are funded for as few as five. Similar variability exists for residential care, with individual service providers caring for between two and 100 children.

During 2012–13, service providers received funding to provide around 1,950 foster care placements each night; however only around 1,550 placements were provided – a difference of around 400. This equates to an average performance level of 80 per cent, although some providers perform at close to 100 per cent while others are performing below 50 per cent. 15

15 This variation in performance, combined with the pricing structure of our funding model, means that some agencies effectively received funding of around $14,000 for each foster care placement they provided, whilst others received in excess of $50,000 per placement.

This mismatch between funding and performance needs to be addressed as part of our reform approach. There is a need to unlock the significant resources invested across the system in order to maximise the impact of the funding we have available.

In recent years, total expenditure on placement and placement support programs by the Victorian Government has increased significantly, and many service providers also report they have invested significant amounts of funding from sources other than government to support children and young people in out-of-home care.

Much of this new investment has been directed towards expanding our capacity to meet the therapeutic needs of children in care – in particular through specific therapeutic residential and home-based care placements. These are important and effective placements, however they are currently available for only a small proportion of the total number of children and young people in care. Over the past five years, the number of children and young people in residential and foster care has risen only slightly – the great majority of growth in placement numbers has been for children in kinship care arrangements.

It is important that we continue to provide more opportunities for children and young people in care to receive the therapeutic care responses many of them need. One way of doing this is to continue to increase the number of therapeutic placements available. However, we also need to make sure that we capitalise on the growing body of knowledge and expertise within the system so that a larger proportion of carers and staff – not just those working in specific therapeutic foster or residential care programs – are equipped to provide therapeutic care responses.

5.3 The balance of investment

Children, young people and families involved with child protection and out-of-home care will often access a wide range of services, such as early childhood, mental health, homelessness, or family violence services. A major aim of the Services Connect reforms is to create more integrated human services across multiple programs and portfolio areas. Through stronger integration and coordination, we seek to create a more effective and efficient response that better meets the needs of vulnerable Victorians.

The analysis below takes a narrower focus, examining five service groupings which many children and families involved with child protection and out-of-home care will access – family support services; specialist placement prevention and reunification services; home-based care; residential care; and leaving care support services. Figure 816 17 illustrates the proportion of funding currently

allocated to each of these services.

16 Department of Human Services data.

17 Variation in the proportion of funding of some services allocated across the Department of Human Services’ four divisions has also been noted – for example the East Division has only 7 per cent of the total state funding for placement prevention services – compared with 38 per cent in the North and South Divisions.

Investment has increased

significantly over the past five

years, but much of the increased

investment is benefitting a

Figure 8: Program funding

The high unit cost of residential care means that it accounts for almost half of all expenditure. While good quality residential care is an essential part of any effective out-of-home care system, we must ensure that it is used only when it is the most appropriate placement option. Residential care cannot be seen as a default ‘placement of last resort’, but must rather be used only when it is the best placement option for a child or young person. As part of our reform directions, as we develop more innovative and flexible approaches to home-based care provision, residential care will increasingly become the preferred placement option only for those young people whose needs and behaviours are so significant that they require a more expert, therapeutic and heavily supervised care response. The reform of the system will need to consider the balance of investment across this spectrum and introduce a broader range of support options. Central to this will be ways in which funding might better support more targeted placement prevention and reunification efforts. While innovative programs such as Stronger Families and the recently expanded Cradle to Kinder programs are having an impact, we must explore more opportunities to improve our approach to family preservation by making better use of existing resources.

Family services play a vital role in preventing the issues that can lead to involvement with child protection and out-of home care. A good case could be made that Victoria’s ability to contain its growth in out-of-home care relative to other jurisdictions has been due in large part to the growth in family services over the past decade.

We must continue to explore opportunities to better leverage off the family services platform to prevent child protection involvement and entry to care. We should also explore how we better utilise the knowledge and skills of family services professionals in the reunification of children with their families. In doing this we must strike a balance with the need for family services to continue to support families at the very early stage of crisis and difficulty.

Family services Placement prevention Home based care Residential care Leaving care 33%

7% 17%

40%

5.4 System integration

In addition to varying levels of investment, the services offered across areas have been fragmented. A key example of this fragmentation is the divide that exists between the delivery of family support, placement prevention, reunification, out-of-home care and leaving care services. Ideally, children, young people and families in any part of the state should have access to a range of integrated, high quality services that prevent placement; offer a wide range of suitable placement types; support reunification; and enable transition to independence. This has not been the case.

Across the state, around 120 organisations are funded to deliver at least one of these five services. Of these, around 90 organisations deliver just one service. Only seven agencies deliver the full spectrum of services. Of these only four deliver the full spectrum within any one Department of Human Services local area.18

While diversity of providers offers service users greater choice and can sometimes stimulate innovation, it is also appropriate to consider whether our current structure facilitates the integrated responses highly vulnerable children, young people and families need.

We need to explore how service integration might be improved in future. This does not necessarily mean that only large organisations capable of delivering a full range of services can be effective in achieving positive client outcomes. But it does mean that we need to pursue much greater integration and coordination of services at the local level.

90 agencies deliver just one

service. Fewer than ten

agencies deliver the full

spectrum of services.

The structure and performance of the system of statutory child protection and out-of-home care have been the focus of a number of reviews and reports over the past decade – each of them highlighting the challenges and shortcomings of the existing system and warning that the entire system is under significant stress.

Within this context the Victorian Government has been pursuing a broad reform agenda, aimed at creating a more integrated, holistic, effective, efficient and sustainable human services system. These reform directions were clearly outlined in the May 2013 publication Services Connect: Better services for Victorians in need, which outlined the vision for a new model of integrated human services delivery in Victoria.

This plan for out-of-home care is based on that vision, and informed by multiple reviews and policy statements, including the Report of the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry (Cummins report). The Cummins report, which was released in February 2012, made 90 recommendations to strengthen and improve the protection and support of vulnerable young Victorians – including the development of this plan for out-of-home care. The Victorian Government’s initial response,

Victoria’s Vulnerable Children – Our Shared Responsibility Directions Paper was released in May 2012. In May 2013, a whole-of-Victorian-Government

strategy, Victoria’s Vulnerable Children – Our Shared Responsibility Strategy 2013–2022 was released. This underlined the shared commitment that exists across government to improve outcomes for vulnerable children, young people and families. It created a performance management framework to monitor these outcomes and committed to the establishment of local cross-government and community networks to drive improved service responses.

On 1 November 2013, Service Sector Reform: a roadmap for community and human services reform was released. This report made several recommendations on the themes of government and the community sector working better together; client and community-led services; more focus on outcomes; reducing red tape; and creating better value. In response, the Victorian Government has adopted a number of principles (see Appendix A) and created the Community Sector Reform Council to advise on the implementation of community and human services reform.

6.1 Reform strategy

Simply tweaking the current system by further increasing funding levels or establishing new stand-alone programs will not lead to the sustainable, systemic improvement we aspire to achieve. More fundamental reform is required to reset how out-of-home is funded and delivered across Victoria. This plan recognises that some reform will take time to be achieved and that we must balance our effort between longer-term enablers and immediate opportunities to achieve the best results. The reform strategy is summarised in Figure 9 on the following page.

Services Connect is the model

for integrated human services

in Victoria, designed to connect

people with the right support,

address the whole range of a

person’s or family’s needs, and

help people build their capabilities

to improve their lives. All of the

out-of-home care reforms will

be based on integration and

workability with this ‘joined-up’

service model that places the

client at the centre of all practice.

Figure 9: Out-of-home care reform strategy

The reform strategy is guided by three overarching goals for out-of-home care. These goals reflect the changes we aspire to achieve for clients, providers, government and the wider community:

> Improved outcomes – improved personal, economic and social outcomes for children and

young people in out-of-home care.

> Reduced demand – slow the growth in the number of children and young people being placed

in out-of-home care over the long-term.

> Sustainable delivery – create the foundation for a more sustainable, efficient and effective

out-of-home care system.

These goals are informed by seven reform directions. Reform directions are necessary to provide a set of more specific criteria against which we can assess the suitability of reform deliverables identified to achieve our overarching goals. The seven reform directions are:

1. Government as commissioner of outcomes. There will be a strong focus on articulating,

measuring and improving outcomes for all children and young people in out-of-home care.

2. Less prescription and more flexibility to support service provider innovation. This will help

inform the design of a more flexible funding model that supports innovation, whilst still ensuring appropriate levels of oversight and accountability.

Improved personal, social and economic outcomes for children

and young people in out-of-home care

Government as commissioner of

outcomes

A more integrated and coordinated service system that

holistically meets client needs

A more collaborative approach to system

governance Processes that support

service co-design between government, service providers and clients

A stronger focus on productivity and efficiency –

maximising public value from investment

Targeted efforts to address overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people in care and

improve their outcomes

Out-of-home care goals

A new funding model A new service delivery platform Longer-term

reform deliverables Reform directions

Reduced growth in the number of children and

young people in out-of-home care

A more sustainable, efficient and effective

out-of-home care system

Less prescription, more flexibility to support service provider innovation

Improve the safety and wellbeing of

children and young people in

residential care

Tender the delivery of therapeutic, outcomes-focused, care and support services Develop a complementary plan for Aboriginal

children and young people Immediate reform actions Implement outcomes monitoring framework Establish more collaborative governance Explore professionalised in-home support Provide additional support to reduce sexual exploitation Increase the focus

on stability and permanency Improve leaving care support Better engage foster carers New approaches to commissioning Trial a new

approach to kinship care

3. A more integrated and coordinated service system that holistically meets client needs. This will include greater integration of services that maintain and reunite families, and those that provide out-of home care; and an improved capacity to provide the placements children need, not just the placements that are available.

4. A more collaborative approach to system governance. Government and service providers at

the central and local level need to work together more effectively to shape long-term reform and address immediate issues impacting on the effectiveness and efficiency of the system.

5. Processes that support service co-design between government, service providers and

clients. Including a more appropriate division of roles and responsibilities between government

and non-government services; and effective, collaborative governance arrangements that support system improvement.

6. A stronger focus on productivity and efficiency – maximising public value from investment.

All governments across the western world are examining ways in which they can maximise the impact of public investment. For out-of-home care in Victoria, government and service providers must work together to identify opportunities to become more productive.

7. Targeted efforts to address overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people in

care and improve their outcomes. The massive overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in

care must be addressed. The complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care will assist with this.

The reform strategy also articulates the longer-term deliverables and immediate actions required to realise the overarching goals of this plan. This approach recognises the need for both an investment in more fundamental system reform – which will take time to design and implement – and more immediate reform opportunities that can be achieved in the shorter-term to deliver early benefits. The longer-term deliverables are:

> A new funding model – we need to change the way we fund to drive a stronger focus on

outcomes; offer more flexibility to service providers to innovate and deliver better services; and unlock the potential impact of our existing resources.

> A new service delivery platform – we need an approach that will create a more integrated and

effective service system. The more immediate actions are to:

> Improve the safety and wellbeing of children and young people in residential care. > Tender the delivery of a new therapeutic, outcomes-focused, care and support service. > Implement outcomes monitoring framework.

> Develop a complementary plan for Aboriginal children and young people. > Establish more collaborative governance arrangements.

> Increase the focus on stability and permanency. > Explore professionalised in-home support.

> Provide additional support to reduce sexual exploitation. > Improve leaving care support.

> Support kinship care. > Support foster carers.

> Develop new approaches to commissioning.

The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of how the plan will be implemented (Section 7); the focus of the long-term reform deliverables (Section 8); and immediate reform actions (Section 9). Together, the longer-term reform deliverables and immediate reform actions form the focus of work for this plan.