The Australian Minimum Wage

and the Needs of a Family

J. Rob Bray

(Jonathan Robbie Bray)

A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of

Philosophy of The Australian National University,

July 2018

© Copyright Jonathan Robbie Bray 2018, Some rights reserved

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Declaration

This thesis is the original work of the author undertaken as a scholar at the Australian National University from 2015 to 2018.

On every page Your eyes engage, The cry’s been - What’s a living wage? The problem’s seen, More ink I ween, Than any

Other that has been -

“The PP” (Southern Times 25 July 1907, 4)

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Abstract

The 1907 Harvester decision effectively established a minimum wage in Australia for men based upon the needs of a family. Commencing in the 1940s Australia has progressively introduced transfer payments to provide support for children and for a parent in a caring role. In 2014 the minimum wage was defined as that for a single person. This thesis is concerned with the rationale of the original decision and the transition between these two states.

The Harvester decision was embedded in the economic and family structure of the day, and in the contribution domestic production made to both living standards and the capacity of a partner to engage in paid employment. In turn, this was underpinned by the nature of domestic technology. The form of the family wage had weaknesses. It was inefficient in meeting its objective of supporting families and involved lower wages for identifiable groups who were not likely to need to support a family (young men and women). However, alternative approaches to family support had not been developed at that time, nor were there suitable institutional arrangements to enable the payment or funding of such assistance.

The transition was slow. Reasons for this include: the speed of permeation of technology for more efficient domestic production; opposition to state financial intervention in families; the need for changes in the structure of employment to encompass part-time work; and at times resistance from organised labour. This resistance was motivated by seeking to protect employment, both of men and single women and because change effectively involved a redistribution of income with losers, as well as winners. In this, the union role can be seen as being representative of the interests of their members. A further challenge related to the interaction of claims for equal pay, and provision for wives without children engaged in domestic production. More generally the institutions involved operated independently with no coordination and change was incremental, building a path determinacy into the development of policies. A number of long-term time series data were developed specifically for this thesis. These data (detailed in appendices) underpin the descriptive and econometric analysis presented and themselves constitute a contribution to the literature. They show that over the period the real value of the minimum wage has increased, although falling relative to other earnings, and with evidence of significant trade-offs of potential gains, in favour of reductions in working time and retirement income. The expansion of family support has significantly boosted household incomes for those with children, and addressed the equity of relative outcomes for families on the minimum wage compared with single workers.

Contents

Abstract ... iii

Contents ... v

List of Appendices ... viii

Tables ... ix

Figures ... xi

Selected Biographical Notes ... xv

Acronyms and Abbreviations ... xix

A note on Currency and Language ... xx

Software... xx

Introduction ... 1

1 1.1 Context – Existing Research ... 2

1.2 Historiography ... 4

1.2.1 Some Areas Not Traversed ... 6

1.3 Structure of Thesis ... 8

The Institutional Framework ... 9

2 2.1 The Nature and Role of Institutions ... 9

2.2 Industrial Relations ... 12

2.2.1 Constitutional Framework ... 13

2.2.2 The Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration and Successors ... 15

2.2.3 Unions and Unionisation ... 17

2.2.4 Employer Organisations ... 22

2.3 Taxes and Transfers ... 23

2.3.1 Income Taxation ... 24

2.3.2 Transfers ... 28

2.4 The Family Wage ... 30

2.4.1 The Economics of a Family Wage ... 31

2.4.2 Was a Family Wage a Family Income? ... 34

2.5 The Household as an Economic Unit ... 37

2.5.1 The Role of Domestic Production ... 39

2.5.2 Household Production and Technology ... 42

2.5.3 Explaining the Pattern of Gender Specialisation ... 47

2.5.4 Population and Maternalism ... 51

2.6 The Labour Market ... 52

2.6.1 Workforce Participation ... 53

2.6.2 Workforce Participation of Women ... 55

2.6.4 Discrimination Against the Employment of Married Women ... 65

2.6.5 Second Earners and Effective Marginal Tax Rates (EMTRs) ... 74

2.6.6 Workforce Participation of Couples ... 76

2.6.7 Working Women and Family and Other Responsibilities ... 77

2.6.8 Women’s Workforce Participation – the Drivers of Change ... 82

2.6.9 Drivers in Australia ... 83

2.7 Equal Pay for Women ... 93

2.8 The Conveyance and Content of Ideas ... 96

2.9 The Economy ... 99

2.10 Summarising the Institutions ... 101

The Australian Minimum Wage ... 103

3 3.1 The Harvester Decision ... 103

3.1.1 Excise Tariff Act ... 105

3.1.2 Ex Parte H.V. McKay ... 105

3.1.3 Assessing the Decision ... 109

3.2 The Male Minimum Wage Post-Harvester ... 120

3.2.1 The Basic Wage and Flow-On ... 120

3.2.2 Adjusting for Price Change – The Development of Indexation ... 122

3.2.3 Royal Commission on the Basic Wage ... 126

3.2.4 Setting the Male Basic Wage 1930 on ... 132

3.2.5 Redefinition of the Role of the Wage ... 139

3.3 The Female Minimum Wage ... 142

3.3.1 Early Decisions ... 143

3.3.2 War and Post-War ... 150

3.4 Conditions ... 154

3.4.1 The Working Week ... 155

3.4.2 Annual Leave ... 157

3.4.3 Superannuation – Deferred Income ... 158

3.5 The Value of the Minimum Wage ... 159

3.5.1 Prices and Living Standards ... 159

3.5.2 The Real Minimum Wage ... 161

3.5.3 Adjusting for Working Time and Conditions ... 165

3.5.4 The Relative Value of the Minimum Wage and Other Earnings . 166 3.6 The Minimum Wage Today ... 168

3.7 Summary – The Development of the Minimum Wage ... 172

State Intervention to Support Families ... 177

4.1.1 Webb, Eder, Wells & Gilmore – Population, Eugenics and

Socialism ... 178

4.1.2 Eleanor Rathbone – Endowment and Equality ... 181

4.1.3 Richard Arthur – Endowment and the Problems of the Basic Wage 182 4.1.4 Other Early Australian Developments ... 185

4.2 Consequences of the Royal Commission on the Basic Wage ... 189

4.2.1 Piddington’s Minute ... 190

4.2.2 Child Endowment in the Commonwealth Public Service ... 192

4.2.3 The Next Step ... 194

4.2.4 Child Endowment in The States ... 196

4.2.5 Political Commitments ... 204

4.3 Royal Commission on Child Endowment 1927-1928 ... 206

4.3.1 The Evidence ... 207

4.3.2 The Report ... 213

4.4 Assessing the Debate ... 216

4.4.1 Motherhood Endowment and Wives ... 216

4.4.2 Resistance – the Speenhamland Effect ... 221

4.4.3 The Union Perspective ... 224

4.5 Child Endowment Introduced ... 226

4.5.1 The Policy ... 231

4.5.2 Child Endowment until the 1970s ... 235

4.6 Developing Family Support – 1975-1990 ... 238

4.6.1 Women and Dependency ... 240

4.6.2 Support for Children ... 240

4.6.3 Supporting a Partner in a Caring Role ... 243

4.6.4 Reflections on the Policy Directions... 245

4.7 Income Tax... 247

4.8 The Court and the Tax and Transfer Systems ... 249

4.9 Assessment ... 250

4.9.1 Experience in Other Countries ... 250

4.9.2 Child Endowment, Other Transfers and Taxes in Australia ... 251

Household Incomes: The Minimum Wage, Taxes and Transfers ... 255

5 5.1 Modelling ... 256

5.2 Modelled Household Disposable Incomes ... 257

5.2.1 Components of Disposable Income ... 258

5.2.2 Components of Income Change ... 261

5.3.1 Trends in Relative Equivalised Disposable Income ... 267

5.4 Summarising Trends in Disposable Income ... 269

Minimum Wages and the Macro Environment ... 271

6 6.1 The Minimum Wage and Unemployment ... 271

6.1.1 The Theoretical Framework ... 272

6.1.2 Australian Analysis ... 276

6.2 The Minimum Wage and Protection ... 278

6.2.1 The Rationale and Australian Experience of Protection ... 279

6.2.2 Brigden, Samuelson and the Australian Case ... 282

6.2.3 The Tariff-Growth Paradox ... 283

6.2.4 Other Australian Analysis ... 284

6.3 Modelling ... 285

6.3.1 Long-Term Structure ... 288

6.3.2 Granger Causality Over the Long Term ... 289

6.3.3 Short-Term Impulse Responses ... 291

6.4 Summary ... 292

Conclusion and Discussion ... 293

7 7.1 The Minimum Wage and its Outcomes ... 293

7.2 Reflecting on the Institutions ... 294

7.3 Some Key Themes... 296

7.4 Some Future Challenges ... 297

References ... 399

List of Appendices

Appendix 1 Note on Census Data ... 301Appendix 2 Derivation of CPI Series ... 305

Appendix 3 The Value of the Minimum Wage 1907–2017 ... 315

Appendix 4 Effective Marginal Tax Rates and Second Earners ... 327

Appendix 5 Modelling – the Minimum Wage and the Macro-Economy ... 335

Appendix 6 Figure Data... 355

[image:10.595.52.481.56.480.2]Tables

Table 2.1 Composition of the Workforce, Women by Marital Status,

1933 ... 63

Table 3.1 Growth in Real Value of the Male Minimum Wage ($2018), Selected Time Periods, 1907 to 2018 ... 163

Table 3.2 Occupations with High Rates of Minimum Wage Employment, 2016, EEH Survey ... 170

Table 4.1 Piddington Minute: Distribution of Male Wage Earners by Family Type, 1911 ... 191

Table 4.2 Piddington Minute: Breakdown of £5/16/0 per Week per Family ... 191

Table 4.3 Piddington’s Identification of Adequately and Inadequately Provided for Households ... 225

Table 4.4 Child Endowment Rates, 1942 to 1976 ... 235

Table 5.1 Composition of Changes in Real Disposable Income Components, Minimum Wage Employees, Three Eras, 1910 to 2015 ... 264

Table 6.1 Vector Error Correction Model: Cointegrating Equations ... 288

Table 6.2 Long Term Granger Causality Test, Minimum Wage and Other Economic Factors, 1908 to 2016 ... 289

Table 6.3 Potential Long-Term Causal Relationship Between the Minimum Wage and Related Economic Factors ... 290

Table A 2.1 Quarterly CPI Estimates, 1907 to 2018 ... 312

Table A 2.2 Data for Figure A 2.1 Measures of Consumer Price Change, Australia, 1901 to 1914 ... 314

Table A 2.3 Data for Figure A 2.2 CPI Components, ABS, McLean and Bray, 1907 to 1914... 314

Table A 2.4 Data for Figure A 2.3 Comparison of Price Indexes, 1907 to 2010 ... 314

Table A 3.1 Minimum Wage Decisions, 1907 to 1923 ... 315

Table A 3.2 Minimum Wage ‘National Wage Case’ and Metal Industries Series, 1978 to 1997 ... 319

Table A 3.3 Female Minimum Wage Relative to Male, 1964 to 1975 ... 320

Table A 3.4 Nominal and Real Value, Minimum Wage by Gender, 1907 to 2018 ... 322

Table A 5.1 Unit Root Testing, 1908 to 2016 ... 339

Table A 5.2 Group Unit Root Testing 1908 to 2016 ... 339

Table A 5.3 Johansen Test, Trace and Max. Eigenvalue test, Type 3 ... 340

Table A 5.4 Vector Error Correction Model: Cointegrating Vectors (β Matrix) ... 342

Table A 5.5 Vector Error Correction Model: Adjustment Vectors (α -Matrix) ... 342

Table A 5.6 VECM: Model Diagnostics... 342

Table A 5.8 Derivation of Modelling Data ... 347 Table A 5.9 Data Used in Econometric Model, 1908 to 2016 ... 348 Table A 5.10 Labour Force Statistics, 1901 to 2016 ... 351 Table A 6.1 Data for Figure 2.1 Trade Unionisation Rate of Wage and

Salary Earners, by Gender, and Female Proportion of Trade Union Members, 1901 to 2016 ... 356 Table A 6.2 Data for Figure 2.3 Commonwealth Taxation and Cash

Transfers as a Proportion of GDP, Financial Year Ending 30 June 1901 to 2016 ... 358 Table A 6.3 Data for Figure 2.5 Production of Candles and Ice Per

Capita, Australia, 1904 to 1975 & Figure 2.6 Relative Share of Production of Coppers and Fuel Stoves, Australia 1949 to 1975 ... 361 Table A 6.4 Data for Figure 2.7 Employment to Population Rate, by

Age Group and Gender, 1911 ... 362 Table A 6.5 Data for Figure 2.8 Wage and Salary Employees, by Age

Group, Gender and Marital Status, 1921 to 2011 ... 363 Table A 6.6 Data for Figure 2.9 Labour Force by Age Group and

Occupational Sector, Women Aged 15 Years and Over, 1911 ... 363 Table A 6.7 Data for Figure 2.10 Employment to Population Rate,

Women Aged 15 to 59 Years, by Marital Status, 1901 to 2016 ... 364 Table A 6.8 Data for Figure 2.11 Employment to Population Rate,

Married women, by Age, Selected Birth Cohorts ... 365 Table A 6.9 Data for Figure 2.12 Employment to Population Rate in

Youth and Mature, Women, Birth Cohorts, 1882-1886 to 1957-1962 ... 367 Table A 6.10 Data for Figure 2.13 Gender Occupational Segregation,

Duncan and Duncan Index, 1891 to 2016 ... 368 Table A 6.11 Data for Figure 2.14 Levels of Educational Attainment, by

Gender, Birth Cohorts 1896-1900 to 1982-1986 ... 369 Table A 6.12 Data for Figure 2.15 Attitudes to Employment of Married

Women and Mothers, Persons Aged 20 to 64 Years, by Gender, 2015 ... 370 Table A 6.13 Data for Figure 2.16 Support for “Traditional Role” of

Married Women, by Age and Gender, 2015 ... 370 Table A 6.14 Source Data for Figure 2.17 Parental Employment

Patterns, Couple Households with Dependent Children Aged Under 15 Years, 1981 to 2017 ... 371 Table A 6.15 Data for Figure 2.18 Employment to Population Rate,

Mothers in Couples with Dependent Children, by Age of Youngest Child, 1981 and 2017 ... 372 Table A 6.16 Data for Figure 2.19 Employment to Population Rate,

Table A 6.17 Data for Figure 2.20 Fertility, Australia, 1860 to 2016 ... 374 Table A 6.18 Data for Figure 2.21 Childcare Use, by Child Age and

Type, 1984 to 2014... 376 Table A 6.19 Data for Figure 2.22 Consumption of Marketised

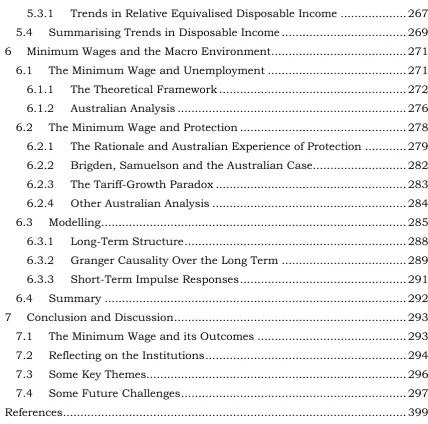

Substitutes for Domestic Production, Couple Families with Dependent Children, 1976 and 2016 ... 377 Table A 6.20 Data for Figure 2.23 Sectoral Shares of GDP, 1900 to

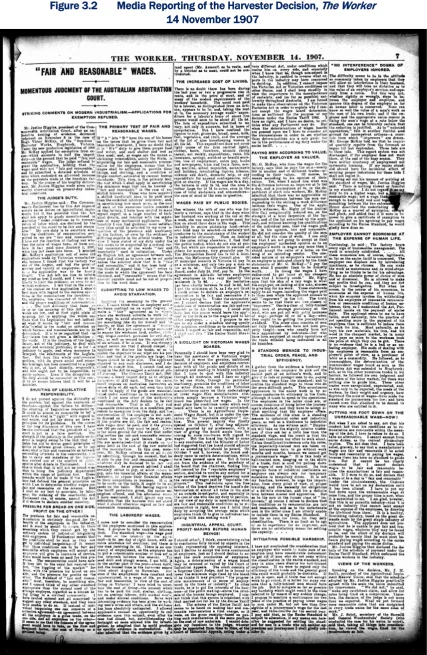

2010 ... 378 Table A 6.21 Figure 3.4 Annual ‘A’ and ‘C’ Price Indexes, 1908 to 1937 .... 380 Table A 6.22 Annual Factory Earnings, Nominal and Real, by Gender ... 381 Table A 6.23 Data for Figure 3.6 Female Earnings as a Proportion of

Male, 1909 to 201 ... 382 Table A 6.24 Data for Figure 3.8 Relative Value of Minimum Wage to

Other Earnings. Men, 1909 to 201 ... 385 Table A 6.25 Data for Figure 3.9 Distribution of Adult Minimum Wage

Employees by Household Income Quintile, 2016 ... 386 Table A 6.26 Data for Figure 4.1 Nominal Value of NSW State and

Commonwealth Jurisdiction Basic Wages, 1923 to 1937 ... 387 Table A 6.27 Data for Figure 4.2 Real Value ($June 1941) of Child

Endowment, 1941 to 1976 ... 388 Table A 6.28 Modelling Results Used in Chapter 5, Disposable Income

Components for a Minimum Wage Worker 1910 to 2015 ... 389 Table A 6.29 Supplementary data for Figure 6.3 Rates of Protection,

Trade Openness and the Minimum Wage, 1908 to 2016 ... 390

Figures

Figure 2.1 Trade Unionisation Rate of Wage and Salary Earners, by Gender, and Female Proportion of Trade Union Members, 1901 to 2016 ... 19 Figure 2.2 Selected Union Campaign Booklets ... 20 Figure 2.3 Commonwealth Taxation and Cash Transfers as a

Proportion of GDP, Financial Year Ending 30 June 1901 to 2016 ... 24 Figure 2.4 Rowntree “Periods of Want and Comparative Plenty” ... 31 Figure 2.5 Production of Candles and Ice Per Capita, Australia, 1904

to 1975 ... 46 Figure 2.6 Relative Share of Production of Coppers and Fuel Stoves,

Australia 1949 to 1975 ... 46 Figure 2.7 Employment to Population Rate, by Age Group and

Gender, 1911 ... 53 Figure 2.8 Wage and Salary Employees, by Age Group, Gender and

Marital Status, 1921 to 2011 ... 55 Figure 2.9 Labour Force by Age Group and Occupational Sector,

Figure 2.10 Employment to Population Rate, Women Aged 15 to 59 Years, by Marital Status, 1901 to 2016 ... 58 Figure 2.11 Employment to Population Rate, Married women, by Age,

Selected Birth Cohorts 1882-1886 to 1977-1981 ... 59 Figure 2.12 Employment to Population Rate in Youth and Mature,

Women, Birth Cohorts, 1882-1886 to 1957-1962 ... 60 Figure 2.13 Gender Occupational Segregation, Duncan and Duncan

Index, 1891 to 2016 ... 61 Figure 2.14 Levels of Educational Attainment, by Gender, Birth

Cohorts 1896-1900 to 1982-1986 ... 64 Figure 2.15 Attitudes to Employment of Married Women and Mothers,

Persons Aged 20 to 64 Years, by Gender, 2015 ... 72 Figure 2.16 Support for “Traditional Role” of Married Women, by Age

and Gender, 2015 ... 73 Figure 2.17 Parental Employment Patterns, Couple Households with

Dependent Children Aged Under 15 Years, 1981 to 2017 ... 76 Figure 2.18 Employment to Population Rate, Mothers in Couples with

Dependent Children, by Age of Youngest Child, 1981 and 2017 ... 77 Figure 2.19 Employment to Population Rate, Women Aged 20-59

Years, by Full-time and Part-Time Employment, Family Status and Caring Responsibilities, 2016 ... 81 Figure 2.20 Fertility, Australia, 1860 to 2016 ... 88 Figure 2.21 Childcare Use, by Child Age and Type, 1984 to 2014 ... 89 Figure 2.22 Consumption of Marketised Substitutes for Domestic

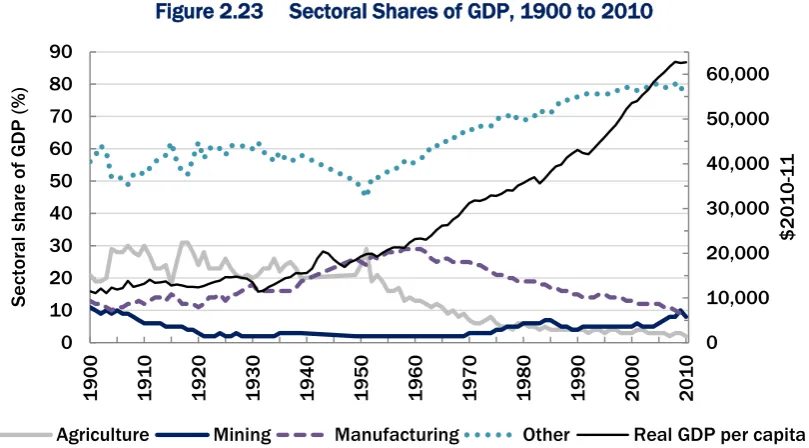

Production, Couple Families with Dependent Children, 1976 and 2016 ... 91 Figure 2.23 Sectoral Shares of GDP, 1900 to 2010 ... 100 Figure 3.1 Minimum Wage, Timeline 1907 to 2016 ... 104 Figure 3.2 Media Reporting of the Harvester Decision, The Worker

14 November 1907... 111 Figure 3.3 Rowntree’s Analysis of Incidence of Inadequate Provision

Associated with Wage-Setting Parameters ... 116 Figure 3.4 Annual ‘A’ and ‘C’ Price Indexes, 1908 to 1937 ... 125 Figure 3.5 Real Value of the Male and Female Minimum Wage

($2018), 1907 to 2018 ... 161 Figure 3.6 Female Earnings as a Proportion of Male, 1909 to 2018 ... 164 Figure 3.7 Real and Effective Value of the Male Minimum Wage,

1907 to 2018 ... 165 Figure 3.8 Relative Value of Minimum Wage to Other Earnings. Men,

1909 to 2017 ... 167 Figure 3.9 Distribution of Adult Minimum Wage Employees by

Household Income Quintile, 2016, HILDA Survey ... 171 Figure 4.1 Nominal Value of NSW State and Commonwealth

Figure 4.2 Real Value ($June 1941) of Child Endowment, 1941 to

1976 ... 236

Figure 4.3 Changes In Social Assistance to Couple Families with Dependent Children, 1941 to 2006 ... 239

Figure 5.1 Real Disposable Income, Minimum Wage Employees, 1910 to 2015 ... 258

Figure 5.2 Real Disposable Income Components, Minimum Wage Employees, 1910 to 2015 ... 260

Figure 5.3 Average Tax Rate, Minimum Wage Employees, 1910 to 2015 ... 261

Figure 5.4 Relative Contribution of Concessional Tax Treatment and Transfers to Household Disposable Income, Couple Family with Two Dependent Children and Single Male Breadwinner on Minimum Wage, 1910 to 2015 ... 261

Figure 5.5 Components of Five Yearly Change in Disposable Income, Minimum Wage Employees, 1910 to 2015 ... 263

Figure 5.6 Real Equivalised Disposable Income, Selected Minimum Wage Employee Households, 1910 to 2015 ... 267

Figure 5.7 Value of Real Equivalised Disposable Income of Single Male and Single Female Minimum Wage Employee Households, Relative to Couple with Dependent Children, 1910 to 2015 ... 268

Figure 6.1 Unemployment Rate and the Minimum Wage, 1908 to 2016 ... 272

Figure 6.2 Impositon of a Minimum Wage in a Perfect Market ... 273

Figure 6.3 Rates of Protection, Trade Openness and the Minimum Wage, 1908 to 2016 ... 280

Figure 6.4 Variables Used In Time Series Modelling, 1908 to 2016 ... 286

Figure A 2.1 Measures of Consumer Price Change, Australia, 1901 to 1914 ... 307

Figure A 2.2 CPI Components, ABS, McLean and Bray, 1907 to 1914 ... 308

Figure A 2.3 Comparison of Price Indexes, 1907 to 2010 ... 310

Figure A 4.1 Effective Marginal Tax Rates, Minimum Wage Employment, January 2017 ... 330

Figure A 4.2 Effective Marginal Tax Rates, Low and Upper-Middle Income Scenarios, Couple Families with Dependent Children, January 2017 ... 332

Figure A 5.1 Log Transformed Variables Used in Modelling, 1908 to 2016 ... 337

Figure A 5.2 First Difference Log Transformed Variables Used in Modelling, 1909 to 2016 ... 338

Figure A 5.3 VECM Unit Roots ... 341

Figure A 5.4 Impulse Response Functions: Minimum Wage Response ... 345

Selected Biographical Notes

Ackerman, Jessie A

(1857-1951) American feminist, social reformer and writer who spent some time in Australia in decades around the beginning of the 20th

century. Author of Australia From a Woman's Point of View

(1913). Arthur, Richard

(1865-1932) NSW non-Labor politician. Minister for Public Health 1927-30 and social reformer. Earliest public advocate for child endowment in Australia (1916).

Asprey, Kenneth William (1905-1993)

Lawyer, appointed as chair of the Commonwealth Taxation Review Committee (1972-1975)

Beeby (Sir) George Stephenson (1869-1942)

NSW Labor/Progressive/Nationalist Politician 1907-1913 and 1916-1920 instrumental in revision of state industrial law. Justice Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration 1928-1941. Chief Judge 1939-1941.

Birrell, Frederick W

1869-1939) South Australian Labor Party politician and later Speaker of the House of Assembly. Former Secretary of the South Australian Trades Hall Council, advocate for arbitration and child endowment.

Brigden, James Bristock (1887-1950)

Australian economist with strong involvement in public policy including as Queensland Statistician. Instrumental in the 1927-1929 inquiry into the Australian tariff.

Bruce, Stanley Melbourne (1st

Viscount Bruce of Melbourne) (1883-1967)

Australian Nationalist (conservative) politician, Treasurer 1921-1923. Prime Minister 1923-1929 (when he lost his seat in landslide loss associated with his industrial relations policies).

Chifley, Joseph Benjamin (Ben) (1885-1951)

Engine driver and trade unionist, Labor Party politician, Prime Minister 1945-1949.

Chipp, Donald Leslie (Don)

(1925-2006)

Australian politician, initially Liberal Party (conservative), including Ministerial appointments, later formed the Australian Democrats (liberal).

Clark, Colin Grant

(1905-1989) English and Australian economist, public servant (including Queensland State Statistician) and academic, including contributing to the development of National Accounts. Cook, (Sir) Joseph

(1860-1947) Australian politician, various representing the Labor Party, Free Trade Party, Anti-Socialist, Liberal, and Nationalist parties in both the NSW and Federal parliaments. Prime Minister 1913-1914.

Copland, (Sir) Douglas (1894-1971)

Australian economist, active in public policy including the Premiers’ plan during the Depression and wartime public servant.

Costello, Peter Howard (1957- )

Cumbrae-Stewart, Zina Beatrice Selwyn (1868-1956)

Australian community worker. Activities included strong involvement with the National Council of Women.

Curtin, John

(1885-1945) Australian Labor Party politician and activist including as journalist and editor, Prime Minister 1941-1945. Member of Royal Commission on Child Endowment 1927-1928.

Daley, Jane (Jean)

(1881-1948) Australian Labor Party organiser and women’s activist. Fraser, John Malcolm

(1930-2015) Australian Liberal Party (conservative) politician, Prime Minister 1975-1983. Giblin, Lyndhurst

Falkiner (1872-1951)

Australian economist and statistician. After a brief period as a Labor politician, career encompassed employment as a public servant, serving on major government bodies, and academic. Member of the Brigden tariff inquiry.

Gilmore, (Dame) Mary Jean

(1865-1962)

Australian poet, utopian socialist, newspaper editor and later communist political activist.

Hawke, Robert (Bob) James Lee (1929- )

Trade Union advocate 1959-1969, ACTU President 1969-1980. Australian Labor Party Politician, Prime Minister 1983-1991.

Heagney, Muriel Agnes (1885-1974)

Australian trade unionist and feminist. Instrumental in establishment of the Council of Action for Equal Pay and Secretary of the Women’s Central Organising Committee of the Labor Party.

Henderson,

(Professor) Ronald Frank

(1917-1994)

Academic, established the Institute of Applied Economic Research at Melbourne University in 1962. Following his academic research into poverty in Melbourne appointed as chair of the Commission of Inquiry into Poverty 1972-1975. Henry, Kenneth Ross

(Ken) (1957-)

Australian public servant and Secretary of the Treasury 2001-2011. Chair of the Australia's Future Tax System (AFTS) Review 2008-2010.

Heydon, Charles Gilbert (1845-1932)

NSW Arbitration Judge 1905-1919. Defined a living wage in his 1905 Sawmillers’ Case.

Higgins, Henry Bournes (H.B.) (1851-1929)

Australian lawyer, liberal (and at times friend of Labor) politician and judge. President Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration 1907-1920, Justice High Court 1906-1929. Involved in writing Australian Constitution and fierce advocate of industrial arbitration as a “new province for law and order”.

Holman, William Arthur (1871-1934)

NSW politician and Premier 1913-1920. Initially a strong Labor activist and trade unionist, and elected Premier as a Labor member. Later moved with other dissenting Labor members to the conservative Nationalist Party following the 1916 conscription referendum.

Holt, Harold Edward

Hughes, William Morris (Billy) (1862-1952)

Australian politician and Prime Minister 1915-1923. Variously leader of five national political parties – from Labor to

conservative (United Australia Party). Keating, Paul

(1944-) Australian Labor Party politician, Prime Minister 1991-1996, Treasurer 1983-1991. Keynes, John

Maynard (1883-1946)

English economist. Author of How to Pay for the War, including proposal for child endowment.

Kingston, Charles Cameron (1850-1908)

Australian lawyer and radical liberal and protectionist

politician (South Australia and Commonwealth). Prominent in development of Australian Constitution and arbitration. Knibbs, (Sir) George

Handley (1858-1929)

First Commonwealth Statistician. In this role undertook broader economic/policy advising role to government.

Lang, John Thomas (Jack)

(1876-1975)

NSW and later federal politician initially Labor Party (although expelled in 1942 and formed independent Labor parties). Premier of NSW: 1925-1927 and oversaw introduction of child endowment; and 1930-1932 when he was removed from office for actions associated with rejection of Depression austerity program.

Longman, Irene Maud

(1877-1964) Women’s and children’s welfare activist, first Queensland female parliamentarian 1929-1932, representing the conservative Country and Progressive National Party. Active in National Council of Women.

McGirr, John Joseph

(1879-1949) NSW Labor Party politician, NSW Minister for Health and Motherhood 1920-1922 and introduced unsuccessful child endowment legislation.

Menzies, (Sir) Robert Gordon

(1894-1978)

Australian politician (Liberal Party and previous conservative parties). Australia’s longest serving Prime Minister: 1939-1941 & 1949-1966.

Monk, Albert Ernest

(1900-1975) Trade unionist, held multiple positions in the trade union movement including variously ACTU Secretary and President 1934-1969.

Muscio, Florence Mildred (1882-1964)

Feminist and social activist, including with the National Council of Women. Member of Royal Commission into Child Endowment 1927-1928.

Piddington, Albert Bathurst (A.B.) (1862-1945)

Lawyer and judge, NSW parliamentarian 1895-1898. Radical liberal. NSW Industrial Commissioner 1926-1929. Was a Royal Commissioner on a number of occasions. Most notably chair of 1919-1920 Royal Commission on the Basic Wage, following which he was a passionate advocate of child endowment.

Powers, (Sir) Charles

(1853-1939) Radical liberal, pre-federation Queensland politician. Appointed to High Court in 1913 and the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, President of the Court 1921-1926.

Rathbone, Eleanor Florence (1872-1946)

Rowntree, B Seebohm

(1871-1954) English industrialist, social researcher. Published studies of poverty in York: 1901: Poverty, A study of Town Life; 1935 & 1951. Reformer who advocated for child allowances and minimum wage in his 1918 book The Human Needs of Labour. Scott Griffiths, Jennie

(1875-1951) American and Australian feminist and activist including in the labour movement. Street, (Lady) Jessie

Mary (1889-1970)

Feminist, social reformer, radical liberal/socialist

internationalist. Active in National Council of Women and Australian Federation of Women Voters. Strong advocate for equal pay and financial independence of married women. Webb, Martha

Beatrice (1858-1943)

English social researcher and reformer, economist, historian and sociologist. Active in the Fabian Society and in founding of the London School of Economics.

Webb, Sidney James

(1859-1947) English economist, writer and social reformer. Fabian, Labour Party politician, had ministerial positions in the MacDonald government.

Wells, Herbert George (HG)

(1866-1946)

Writer of science fiction and social commentary. Utopian socialist and Fabian. Possibly first exponent of child endowment.

Whitlam, Edward Gough

(1916-2014)

Acronyms and Abbreviations

ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics (formerly Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics)

ACTU Australian Council of Trade Unions

AEU Amalgamated Engineering Union

AFPC Australian Fair Pay Commission

ALP Australian Labor Party1

AMWSU Amalgamated Metal Workers’ and Shipwrights’ Union

APSC Australian Public Service Commission

AWE Average Weekly Earnings

AWU Australian Workers’ Union

CAR Commonwealth Arbitration Reports

CBD Central Business District

CEHA Cambridge Economic History of Australia

CLR Commonwealth Law Reports

CPI Consumer Price Index

CURF Confidentialised Unit Record File

DLP Democratic Labour Party

EEH Survey ABS Survey of Employee Earnings and Hours

EMTR Effective Marginal Tax Rate

FMW Federal Minimum Wage

FT Full-Time

FTB Family Tax Benefit

GDP Gross Domestic Product

HATTS A Tax-Transfer Model

HCCA Home Child Care Allowance

HILDA Survey Household Income and Labour Dynamics Australia Survey

LITO Low-Income Tax Offset

NCW National Council of Women

NSW New South Wales

NWC National Wage Case

OHM A Tax-Transfer Model

PAM A Tax-Transfer Model

PSMPC Public Service and Merit Protection Commission

RCCE Royal Commission on Child Endowment or Family Allowances

1 Reference is made in the text to both the Australian Labor Party and Australian

(1927-1928)

SMBW Single Male Breadwinner

SNA Safety Net Award

SNR Safety Net Review

TFR Total Fertility Rate

UAP United Australia Party

VAR Vector Autoregression

VECM Vector Error Correction Model

WA Western Australia

WCTU Women’s Christian Temperance Union

WEB Women’s Employment Board

A note on Currency and Language

Currency

Values are cited in both imperial and decimal currencies. Australia adopted decimal currency in 1966 with the dollar having a value of 10 shillings.

Under the imperial system there were 20 shillings (s.) in the pound (£) and 12 pennies/pence (d.) in a shilling. Currency values in this system were presented in various fashions. Amounts were at times cited in shilling values even when above a pound in value, and in textual terms were presented in a range of formats, often abbreviated using a diagonal slash, for example 5/6 to represent 5s. 6d.

Language

Language use and spelling has varied over the period under study. In general the approach has been to maintain original orthography in quotes. This includes the use of terms such as ‘statist’ rather than ‘statistician’, and spelling differences such as ‘employés’, rather than ‘employees’, ‘shew’ rather than ‘show’ and the use of ‘&c’ as an abbreviation for etcetera.

In addition where italics are used in quotations this reflects, unless otherwise noted, transcription from the original.

Software

Introduction

1

In his 1907 ‘Harvester’ decision, Justice Henry Bournes Higgins, President of the Australian Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration set a minimum wage for adult male workers employed by a manufacturer of agricultural machinery which he deemed to be “fair and reasonable” for a man, his wife and children living in “a labourer’s home of about five persons” (2 CAR 1, 3 & 6). In 2014 the Fair Work Commission declared: “The appropriate reference household for the purposes of setting minimum wages is the single person household, rather than the couple household with children” (245 IR 1, 11), and this wage is paid equally to males and females. Today, in contrast to 1907, the needs of a couple family, such as that for which the Harvester decision was made, are met through the workforce participation of both partners, government transfer payments for the support of children, and access to government transfers for a dependent partner while children are young.

This thesis is concerned with the rationales for these stances, and the transition between these two states, including when and how it occurred, and the role of the state, the economy and other institutions.

Specifically it considers the establishment and evolution of the minimum wage, the development of public transfers to families with children, and the treatment of families in the income tax system. These are considered as elements of the institutional structure of Australia, including the economic forces which prevailed. With a focus on the minimum wage, the study is primarily concerned with the low paid. Many of the considerations however extend beyond this group.

The contribution of this thesis is providing a coherent and quantitative, narrative which is focused by an understanding of the economic drivers of change. Uniquely this thesis draws together the core elements of wages, employment participation, taxation and transfers, in contrast to other empirical studies which largely focus on just one of these elements, and more general historical accounts which frequently generalise, rather than analyse, the empirical evidence and underemphasise the underlying economic forces. The research involved the creation of a number of historical time series which underpin the analysis.

specialisation by the male in market, and the woman in domestic, production. This latter form of production was essential to enable the first, and directly contributed to the wellbeing of all members of the household. This domestic production was significantly shaped by the extant domestic technology

The Harvester decision was though a crude solution to meeting family needs. However, options were limited. Alternative mechanisms not just required the further development of the state, but also did not necessarily wholly address the tensions between the family basis of the wage, the principle of equal pay for men and women, and the low level of female participation in the paid workforce, especially by married women. Additionally, once the concept of the family wage was entrenched, shifting family support from the wages system produced losers as well as winners. Policy responses were slow in coming, partial, and frequently neglected over time, and faced resistance from those opposed to such an extension of the state role.

While some changes to this framework occurred in the Second World War, it was not until the final quarter of the twentieth century that dramatic restructuring occurred. Key elements of this were the granting of equal pay and the transition of the minimum wage to a wage for a single person. This was largely effected by an ongoing decline in the value relative to other earnings, and the expansion of transfers for families, along with a collapse of the single male breadwinner model with strong increases in the participation of married women in the paid workforce, complemented by the extensive penetration of new domestic technology.

In large part these changes were not the product of a strategic policy intent, but rather can be seen more as a weakening of older arrangements as the rationale for these was diminished by economic development and shifts in other elements of the framework.

1.1

C

ONTEXT–

E

XISTINGR

ESEARCHBecker (1991) as well as critiques of this (Wooley (1993 & 1996), Ferber (1995) and Nelson 1995)) which is drawn upon in later sections, along with more recent insights including Stevenson and Wolfers (2008).

The question of the family wage, and the male breadwinner is well addressed in the literature, albeit with much of the focus being on the historical roots of this form of family income, and a strong European focus. The literature includes Seccombe (1986), Horrel and Humphries (1995 & 1997), Creighton (1996a & 1996b), Janssens (1997) and Burnette (2008). As however identified by Hill (1993), the roots of this literature go much deeper to include works such as Clark (1919) and Pinchbeck (1930). Associated with this is the work of Goldin (1995) who considers the obverse of the role of the single male breadwinner, the pattern of female workforce participation. This is considered further in section 2.5.3. Edwards (1984) considers the internal structure of the household economy in Australia with a focus on taxes and transfers.

In addition to the historical literature, including Douglas (1925) documenting the early developments of child endowment, there is a smaller but still significant contemporary literature on the family wage and welfare system especially the introduction of child allowances. This includes Dyhouse (1989), Macnicol (1992), Pedersen (1993) and Koven and Michel (1993), and is considered in section 4.9, but again has a strong European focus.

There is also very extensive literature, both academic and non-academic, on the history of equal pay for women and of women’s employment in Australia. While impinging on the issues considered here, the framing of most of this does not directly focus on them.2 This can be seen with respect to the family

basis of the minimum wage decisions. While this literature recognises, or in some cases demonises, the family wage as an impediment to gender wage equity, there is less attention on the reasons why the wage was structured in this way, and the economic and institutional factors behind its persistence and later transformation.

In contrast to the more atomised approaches exemplified in much of the above, two approaches: the ‘Wage Earners’ Welfare State’; and the ‘Australian Settlement’, seek to place many of the key elements to be considered here in an integrated framework.

The concept of the ‘wage earners’ welfare-state’ was developed by Castles (1985, 102-109) who described the development of social protection in Australia, in contrast to other market economies, as being where “a welfare state through state expenditure was, in quite large part, pre-empted by a

2 There are some notable exceptions. These include Bennett (1984) who critiques this

welfare state through wage regulation” (1994, 124). He describes the elements of this as: the control of wages through quasi-judicial activity of the state, the use of tariff policy to protect the manufacturing sector and enable high wages; and the regulation of migration to protect the bargaining position of labour. Although providing some insights, for the considerations here, this approach is limited. It does not provide an effective framework for considering change, nor the tensions seen in the wage-setting process, or the interaction with family support. Additionally, as considered in Chapter 6, the purported role of industry protection is questionable.

Later these same three elements: Protection; Arbitration; and White Australia, were termed by Gerard Henderson (1990, 5-7) as the ‘Australian Trifecta” although his analysis was primarily concerned with the economic and social changes in Australia from the 1960s onwards.

Kelly (1994) introduced the conceptualisation of the ‘Australian Settlement’. This can be seen as an expansion of the above approaches. Kelly posited that there were five ideas: “White Australia, Industry Protection, Wage Arbitration, State Paternalism, and Imperial Benevolence” (1-2), which marked what he saw as ‘the old order’ of Australia, which had essentially operated from federation until the 1980s. He argues that support for these ideas was “bipartisan … accepted, sooner or later, by Liberal, conservative and Labor politicians [and] its universality provided the bonds for eight decades of national unity and progress despite its defects” (1). As with Castles and Henderson this conceptualisation is not considered to provide an effective framework for the consideration of the changes here which more frequently display a dynamic within the period of the postulated ‘settlement’. As such, this concept again ignores the tensions between policies. In part this can be attributed to the extent this framework, similar to the approach adopted by Henderson, was developed to hypothesise a transition from a ‘closed’ to an ‘open’ economy, which sought to dichotomise the two eras, rather than address change which may have occurred within.

1.2

H

ISTORIOGRAPHYThe broad approach of this thesis is institutional, recognising as institutions not only formal bodies such as the arbitration court and governments, but also the policies and programs which emanate from them, such as the minimum wage and transfer payments, as well as the institutions of the family and the labour market. The approach recognises that these institutions have both agency and the capacity to change, but they can be constrained by other institutions, the cost of change, and by past history which may limit the pathways that can be pursued. In a broader sense these institutions are the product of a wider set of relationships, in particular the capacity and extent of individuals to meet their needs, and their desires, in terms of both production and consumption, and the welfare they gain from this – those functions we consider as economics.

This study contains three central elements:

• Deriving a time series of the value of the minimum wage, and of its interaction with the tax and transfer system for selected family types, to enable changes to be observed and interpreted; and

• Building an understanding of the interrelationship between the elements and the way, and reasons why, these institutions changed. Of particular interest is that of path dependence – that is, the extent to which earlier institutional structures acted to shape or constrain future development. While the focus is on the historical, the underlying motivation for studying this is to gain insight to inform current and future developments. In this regard, while it is acknowledged that the minimum wage today is effectively a safety-net provision with only a small proportion of the Australian workforce reliant upon it, it remains significant in concept, and decisions about it have wider ramifications within the wage-setting environment.

Such an approach is not foreign to these considerations. Justice Higgins, as already seen, a central player in this history, reflected on the path he chose in his Harvester decision in the light of emerging arguments for new institutions, such as child endowment, declaring:

Perhaps it is sufficient to say that when I gave what is called the “Harvester decision” in 1907 … the decision would have been materially different if any such direct provision existed for wives and children; the basic wage, if any, might not have taken the maintenance of wives and children into account at all. But there was no such direct provision; and there is none yet (in Australia); and the Court has to deal with facts as they exist. (Higgins 1926, 9)

While some ‘facts’ such as the existence of institutions can be postulated with certainty, although their functional capacity less so, more broadly, as argued by Carr: “the facts of history cannot be purely objective, since they become facts of history only in virtue of the significance attached to them by the historian” ([1961] 2008, 120).3 More so here I draw upon diverse sources:

decisions of the arbitration court, judgements frequently drafted as rationalisations for decisions in a quasi-legal form with an eye towards an appearance of consistency with precedent and political expediency; statements of politicians and others in promising, opposing and announcing policies with the intent of providing the best interpretation of their actions, and differentiation with, or deprecation of, their political adversaries; as well as the declarations and claims of unions and other advocacy groups which are frequently couched in terms of the strongest argument that can be mustered with respect to the specific circumstances. In addition, none of these voices can be considered to be monolithic. Rather, each is characterised by diversity, within and across time. Much material has been garnered from newspapers. These are not without their agendas, and in particular for the subject here, the low paid, tend to be pitched at the middle class and their aspirations, as well as being, at times, as much about sensationalism and entertainment as the

3 This applies equally to the economist who seeks to identify the most parsimonious

recording of ‘fact’. Also it is a history marked by lacunae: women are substantially absent in much of the material, especially labour histories, and at best only gleanings of information on the actual standards of living of the low paid can be obtained, let alone their daily behaviours, routines, motives and aspirations.

Similarly most of the data used in analysis, ranging from subjects such as marital and employment status, through to levels of price change, cannot be separated from the definitions and rules that were in place at the time of their collection, which were in turn frequently shaped by the social and economic conventions of the time.4

1.2.1

S

OMEA

REASN

OTT

RAVERSEDThere are three recurrent themes, integral to the institutions and debates with which this thesis is concerned, which are not addressed.

The first is race. It can be argued, as is done in the conceptualisation of the ‘Australian Settlement’, that race and the White Australia policy, in particular those elements specifically framed in terms of avoiding competition from ‘coloured’ and ‘Asiatic’ labour, were central to the debates on many of the questions considered here.5,6 This is undoubtedly true, however set against

this, the question is whether or not under a less racist mindset, and without the adoption of racially discriminatory policies for migration, and in the treatment of Indigenous Australians, the institutions, decisions and outcomes considered here would have been materially different. My answer to this is that, unless one postulates quite different pathways of Australian demographic and economic development, for example an alternative pattern of colonial development, or the development of a plantation style economy with

4 Nor are these sources free from the limitations associated with data reporting and

collection.

5 While racist these declarations were frequently nuanced, and portrayed more

complex relationships between class, xenophobia and race. Hence the policy advocated by The Bulletin in 1893: “Australia for Australians The cheap Chinaman, the cheap Nigger, and the cheap European pauper to be absolutely excluded” (cited in Clark [1957] 1977, 447). Clyde Cameron writes that it was only in 1974 that the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU), at his behest, changed its rules that debarred from membership persons of non-European descent, although noting that these exclusions had historically not applied to “an Australian Aboriginal, or Maori, or Negro citizen of the United States of America” (1996, 175).

6 It is also not just an Australian phenomenon. As detailed in section 4.1.1 some of the

the use of indentured labour, pathways effectively shut at the time of federation, such a case is not persuasive. This in no way however should be interpreted as denying the gross injustices that did occur, and indeed are perpetuated today.

The second is that of fertility and pro-natalist policies, and their association with eugenics, issues not unrelated in the debate to the first, and at least nominally raised in debates on family policies including wages and transfers. A recurrent theme across the era considered here was that of the Australian birth rate. This is a concern stretching from the 1904 New South Wales Royal Commission into the Birth-Rate which ascribed the fall in the birth rate to “selfishness … the desire of the individual to avoid his obligations to the community” (cited in Hicks 1978, 23), to the 2006 declaration of the then Treasurer: “if you have the opportunity … have one for mum, one for dad and one for the country” (Costello 2006). Again, in considering this my focus is on whether or not it would have made a material difference to the institutions, policies and outcomes if these debates and policies had not occurred. My conclusion is that any such difference would have been marginal, but rather, as discussed later, fertility trends can be seen in terms of a wider set of economic and social factors, separate to any particular pro-natalist policies.7

The third is gender. In this respect the qualification is not so much that this subject is absent, but rather that exploration of several significant dimensions is curtailed.8 Hence while certain aspects of gender will be discussed, at times

in some detail, in terms of the setting of the female minimum wage, female workforce participation and gender division of functions within families, the context of this is focused on the nature of these institutions as they existed and evolved over time, rather than the specific implications for women, or any theoretical or normative position as to what they should have been.

7 Some caution needs to be exercised in the consideration of concepts such as

‘pro-natalism’. It can be considered in more neutral terms as ‘population policy’, and in this regard ‘pro-natalism’ can be viewed as having a range of meanings, including the role of endogenous population reproduction and/or growth relative to migration, that is nativist rather than natalist. While often associated with the idea of ‘Maternal Citizenship’, that is, where a woman’s identity in relation to the state is bound with being a mother, the concepts are quite separate.

8 This can be seen for example in the treatment of families, which are here conceived

of in terms broadly consistent with de Vries’ (2008, 10) postulation of “the family-based household is an entity that performs functions of reproduction, production, consumption, and resource distribution among its members”.

It is recognised that within this type of conceptualisation there are substantial gender questions. Crucially these include the extent to which there are power imbalances between individuals in such a unit, and the implications of this for women, both within the institution of the family itself, and more widely. That is, within this definition, who determines who undertakes these ‘functions’, and who determines the balance of ‘resource distribution’.

1.3

S

TRUCTURE OFT

HESISThis thesis is structured as follows:

• Chapter two identifies some of the key institutional elements: the Industrial Relations System; the development of the tax and transfer systems; the family and domestic production;9 patterns of employment in the paid

workforce; the conveyance of ideas; and the wider economic settings. This is a substantial chapter which also provides a backdrop to the considerations in subsequent chapters.

• Chapter three documents and analyses the development of the Australian minimum wage since 1907, including the development of a separate wage for women between 1912 and 1975.

• Chapter four is concerned with the provision of support to families through the welfare system, including the initial development of the concept of this form of intervention, and the process of implementation and subsequent developments.

• Chapter five presents the results of a quinquennial modelling of the interaction of the minimum wage and the tax/transfer system. It considers the outcomes for a single adult male and female, and for a classical “Harvester” family of a single adult male breadwinner with a partner who works in the domestic sphere only and children.

• Chapter six presents an analysis of the minimum wage and the wider economy. This includes an econometric examination of the relationship between the wage, tariffs and unemployment between 1908 and 2016. • The final chapter identifies some salient issues arising from this analysis.

9 Here the focus is on domestic production in the context of relatively low waged

The Institutional Framework

2

This chapter identifies and discusses the key institutions in the context of the minimum wage and assistance to families. These are extensive and include: the industrial relations framework; the tax and transfer systems; the conceptual basis of the family wage; the economics of a household; the paid labour market, with a particular focus on the labour market position of women, including married women and the barriers and constraints they may have faced; how ideas were conveyed, including the extent to which Australian consideration of questions around wages and the family were influenced by international debate; and a very brief overview of the structure of the Australian economy over the period.

Before entering into the detail of these, there is merit in first addressing the nature of institutions.

2.1

T

HEN

ATURE ANDR

OLE OFI

NSTITUTIONSNorth describes institutions, and their importance to understanding historical economic performance as:

Institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction. They consist of both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights). Throughout history, institutions have been devised by human beings to create order and reduce uncertainty in exchange. Together with the standard constraints of economics they define the choice set and therefore determine transaction and production costs and hence the profitability and feasibility of engaging in economic activity. They evolve incrementally, connecting the past with the present and the future; history in consequence is largely a story of institutional evolution in which the historical performance of economies can only be understood as a part of a sequential story. (North 1991, 97)10

While some of these constraints are embedded in individual behaviour and belief structures, these in turn are frequently shaped by wider community values and expectations. In other cases the institutions take on a much more concrete form – such as the bodies tasked with the enforcement of the formal

10 A somewhat simpler definition is given by Commons in defining ‘Institutional

rules. Others, such as the minimum wage itself, take on both a concrete existence, as well as being an ethical symbol.

North’s definition here focuses on the role of these institutions in minimising transaction costs. That is, greater efficiency can be derived from the existence of the institution. A particular case, important to the subjects under discussion here, are the transaction costs of collective action. This question of efficiency also has both a long-term and short-term dimensions. Given the nature of the markets considered here, in particular the labour market, institutions need not just resolve an individual exchange at a point in time, but also enable longer-term relationships. Equally, the reduction of uncertainty with respect to family formation and reproduction requires institutional responses with a long-term focus.

In focusing on the efficiency of institutions, care needs to be taken in recognising that preference sets cover not just aspects of material wellbeing but also preferences as to the nature of relationships at the individual and societal level. North opens this scope, cautioning “however concerns about equity as well as the distribution of gains from trade, influence people’s views about the fairness and justness of contracts” (1986, 233). This is important to the subject here not just because of the existence of different preference sets, but because the question of ‘fairness’ is one, which in Sen’s terminology, is dependent upon the space in which it is considered. This question is explored further in section 2.7.

North argues that change arises from “fundamental and persistent changes in relative prices, which lead one or both parties to contracts to perceive they could be better off by alterations in the contract” (234). While this can be seen as one potential cause, some caution needs to be given to any assumption that an outcome, or institution, at any one time represents a stable equilibrium.11

While institutions can be seen as a means of coordination and improving efficiency, they can also provide opportunities for rent-seeking behaviour, and to the extent they seek to encapsulate some norms, these do not necessarily reflect the diversity of individual preferences or circumstances, and hence provide some with greater benefits than others. 12 Under more extreme

circumstances they can lose focus on their initial rationale, and become self-interested, or their purpose becomes poorly understood, and rather than just creating order to minimise transaction costs, they seek to preserve a particular form of order.13 In time however this conduct becomes costly and may

generate pressure for change.

11 This stability can be seen both in terms of classical interpretation of an equilibrium

to which a market may return after an exogenous shock, and in a political sense, of the extent of commitment to the achieved outcome or institution.

12 That is while they may reduce transaction costs and reduce uncertainty for some,

they may increase it for others.

13 Olson in his book The Rise and Decline of Nations describes this type of process in

Institutional change can, and indeed in most cases tends to, be incremental, rather than revolutionary. A number of factors contribute to this. The first is the sunk-cost associated with the establishment of an institution, and the high transaction, including coordinating, costs of change. This is exacerbated by the extent to which there is risk attached to the change. Secondly are the issues associated with rent seeking, including the degree these institutions will seek to minimise change to maximise the preservation of rents. Thirdly are constraints because of the interrelationships with other institutions as part of a wider system. To the extent change is incremental, and the development of new institutions costly, change can often be seen as being path dependent. That is, to the extent it occurs and new institutions are developed, the set of options can be constrained by what has gone before. Such path dependence however should not be construed to mean that change is path determined. Rather, within a set of constraints, a range of options are available for change. Nor should it be seen as being limited to mere incrementalism. That is where the gains are high, new institutions can be established, whether of a formal or informal nature, which can be radically at odds with what went before.14

A further challenge for institutions is that in their role of codifying a particular structure they can face difficulties in coping with major paradigm shifts, or the coexistence of, and or transition between, two opposed paradigms or sets of constrained preference sets.15

Richter (2005) suggests that North’s concept of a ‘New Institutional Economic History’ relates to the interaction between the “polity and the economy” (177) before stating “North assumes imperfect individual rationality and emphasizes the role of ideology”, although Zimbauer’s characterisation of “imperfect information and bounded rationality” (2001, 10) is probably a more useful expression.

Coase, in reference to ‘New Institutional Economics’ emphasises that “modern institutional economics should study man as he is, acting within the constraints imposed by real institutions. Modern institutional economics is economics as it ought to be” (1984, 231). This is not to omit however the fundamental economic drivers, and their basis. Here he observes, with respect to earlier American institutionalists, that they “were not theoretical but anti-theoretical … without a theory they had nothing to pass on except a mass of descriptive material waiting for a theory, or a fire” (230).

While these theoretical considerations around institutions are important, they are not the focus here. As discussed by Steinmo (2008, 118), although the terminology of ‘Historical Institutionalism’ was not coined until the 1990s, this

14 It is in this sense that the sequential nature of history and institutions to which

North alludes can be understood. Such sequences are not just independent episodes occurring one after another, but rather are processes, or a series of outcomes and institutions, that can be related to what has come before.

15 This as will be seen later can be viewed as the challenge Australian institutions

post-dated the application of this approach by at least several decades, if not half a century.16

2.2

I

NDUSTRIALR

ELATIONSThe focus here is on the ‘minimum wage’, as determined in the federal industrial relations arena. While this focus is well founded, some limitations need to be recognised.

Prior to the Harvester decision a range of minimum rates of pay had been developed in Australia in many industry sectors, in particular through the activities of wages boards in a number of states.17 Along with contemporary

developments in New Zealand, the minimum wages established by Wages Boards under the Victorian Factories and Shops Act 1896 (Vic), were amongst the first independently established minimum wages in the world.18 These

Boards, comprised of equal numbers of employers and employees with an independent chair, had the power to determine minimum wages (and piece rates) within industries. While the scope of these Boards was limited (Price 2009) and focused in particular on industries with ‘sweated labour’, at the time their impact on earnings was seen as significant. The Victorian Government Statist reported in 1904, for example: “the average weekly wage for all employés (including boys) in the bread-making trade was £1 12s. 6d. in 1896, prior to the Wages Board being in operation, and £2 2s. 1d. in 1903

16 This is of course not the only approach to institutions. Marxist analysis would, for

example, see institutions in terms of class interests, while feminist analysis would emphasise the role of power in patriarchal structures.

17 Sawkins identifies Sir Samuel Griffith’s 1890 ‘natural law’ Bill in the Queensland

Parliament as the first enunciation of the family wage concept in Australia. He cites this as: “The natural and proper measure of wages is such a sum as is a fair immediate recompense for the labour for which they are paid, having regard to its [the labour’s] character and duration; but it [the wage] can never be taken at a less sum than such as is sufficient to maintain the labourer and his family in a state of health and reasonable comfort” (1933, 9).

18 There is an extensive, and mostly positive, literature on the activities of these

boards. This includes: Pember Reeves ([1902] 1969), Webb (1912), and Hammond (1913). Collier (1915) concludes “the Victorian system of wages boards was designed to remedy some of the worst evils of sweating and underpayment. In doing this it has been eminently successful” (1953). In contrast Rankin (1916) tends towards more negative conclusions. Looking at the boot trade she argues “the Trade would seem to have been regulated for the benefit of the Importer” (92), in the furniture trade that the board had “aided the [unregulated] Chinese in obtaining a surer foothold … [and] tended to increase the undercutting of prices by the multiplication of the one-man workshop” (96-97). In the bread trade she says “the regulations seem only to be obeyed if they are found to be convenient (99), while she concludes the clothing trade would have “expanded considerably farther” (103) if not for the boards and that there was no major impact on rates in the shirt trade or underclothing, except when there was a shortage of labour (105-107).

when its determination was in full force” (ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 1301.2 1904, 180). 19,

In addition, for most of the twentieth century only a minority of Australian employees were directly subject to the jurisdiction of the federal industrial relations system. Even in 1968, it was estimated that 40.1 per cent of employees were under Commonwealth Awards with 47.3 per cent covered by State Awards and the remaining 12.7 per cent outside of the award system (ABS 6101.0 1970, 166). Notwithstanding this, as will be discussed, the decisions taken in the Federal jurisdiction, in particular relating to the minimum wage, were highly influential on state tribunals for most of the period.

2.2.1

C

ONSTITUTIONALF

RAMEWORKCentral to the development of the Australian minimum wage was the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, and its successors. The court was established in 1905, under the provisions of the Commonwealth

Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth) which in turn drew upon s.51(xxxv)

of the Australian Constitution which granted the Commonwealth Parliament the power to legislate20 with respect to “conciliation and arbitration for the

prevention and settlement of industrial disputes extending beyond the limits of any one State”. This provision did not exist in the first draft of the Australian Constitution and was only present in the final by a narrow margin.21

19 The Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics became the Australian Bureau

of Statistics in 1974. Here all publications are attributed to the latter organisation and references are given as ABS with the publication catalogue number and date where this is available.

20 The Australian Constitution is based on the principle that the Commonwealth has

legislative powers limited to domains identified in Section 51 of the Constitution, with all other matters being left to the states.

21 Following the 1890 Federation Conference which agreed on the need for the union of

the colonies, two Constitutional Conventions were held. The first, in 1891, involving delegates from the colonial legislatures developed an initial draft constitution. The second, comprised delegates elected by popular vote (although with limited suffrage), was held in 1897–98 and focused on refining this. Between these, in a period which was marked by a significant economic recession and some disputation and loss of interest in federation, two ‘people’s conventions’, in Corowa in 1893 and Bathurst in 1896, sought to maintain the momentum of the federation project.