Management Accounting

SOAS, University of London This edition: 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this course material may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, including photocopying and recording, or in information storage or retrieval systems, without written permission from the Centre for Financial & Management Studies, SOAS, University of London.

Course Introduction and Overview

Contents

1

Course Objectives 22

The Course Author 23

Course Structure 24

Overview of the Course 45

Learning Outcomes 56

Study Materials 57

Teaching and Learning Strategy 51 Course

Objectives

Welcome to the course Management Accounting. Accounting information is a fundamental resource for enabling managers to make decisions. This course emphasises a critical understanding of the accounting numbers, the under-lying assumptions behind those numbers, and the choice of accounting tools and techniques that will best suit managers’ information needs. The aim of the course is to equip line managers primarily in business (but also public-sector agencies) with the ability to prepare budgets, develop business cases for capital investment, calculate prices and exercise cost control.

The course uses a range of simulations, case studies and real-life problems in addressing variations in practice between industry sectors and geographical regions. A plain English style is used throughout the course that addresses the needs of European, Asian, African and Arabic-speaking students.

2

The Course Author

Matthew Haigh PhD (Macquarie) has had careers in public-sector auditing,

chartered accountancy and internal auditing. He has researched and lectured in eight European countries and currently holds a Senior Lectureship in Accounting at the University of London. He holds qualifications in chartered accountancy and certified information systems auditing. His roles in commer-cial and public-sector organizations have focussed on the production, review and audit of management and financial accounting information.

3 Course

Structure

The course consists of eight units, each of which comprises a set of readings, questions and exercises.

Unit 1 The Context of Management Accounting

1.1 Introduction to Management Accounting

1.2 Shareholder Value and Management Control Systems 1.3 Non-financial Accounting Information

1.4 Summary and Practice Tasks 1.5

Case Study

Unit 2 Pricing and Production-Volume Decisions

2.1

Pricing Strategy

2.2

Relevant Costs for Pricing Decisions

2.3

Finding the Break-Even Point – Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis

2.4

Achieving a Target Profit Using Break-Even Analysis

2.5

Using ‘Contribution’ to Make Decisions

2.6

Segmental Profitability Analysis for Closing-Continuation Decisions

2.7

Summary and Practice Tasks

Unit 3 Production Decisions, the Value Chain and Production Capacity

3.1

The Value Chain

3.2

Production Capacity

3.3

Theory of Constraints, Relevant Cost, Opportunity Cost

3.4

The Outsourcing Decision

3.5

Costing Orders

3.6

The Product-Mix Decision

3.7

Environmental Costs

3.8

Summary and Practice Tasks

3.9

Case Study

Unit 4 Volume-Based Cost Systems

4.1

The Problem of Allocating Production Costs

4.2

Variable Costing and Absorption Costing

4.3

Throughput Costing and Process Costing

4.4

Job Costing

4.5

Summary and Practice Tasks

4.6

Case Study

Unit 5 Activity-Based Cost Systems I

5.1

Classifying Costs Using Value-Chain Activities

5.2

Types of Activities: Facility-Level, Customer-Level, Product-Level, Batch-Level, Unit-Level

5.3

Steps in Designing an Activity-Based Cost System

5.4

Summary

Unit 6 Activity-Based Cost Systems II

6.1

Using the Activity Model to Forecast Resource Capacity

6.2

Organisation-Level Factors Affecting Activity-Based Costing Systems

6.3

Summary and Practice Tasks

6.4

Case Studies

Unit 7 Capital Investment Decisions

7.1

Introduction To Capital Investment Decisions

7.2

Accounting Rate of Return

7.3

Payback

7.4

Discounted Cash Flow Techniques

7.5

Taxes and Price Inflation

7.6

Practice Tasks

7.7

Problems

Unit 8 Performance Measurement Systems and Strategic Budgeting

8.1

Business Units, Responsibility Centres, Cost Centres, Profit Centres, Investment Centres

8.2

Divisional Performance and the Controllability Construct

8.3

Transfer Pricing

8.4

Profit and Cash Budgets

4

Overview of the Course

Unit 1 introduces management accounting by establishing its role in the

business organisation. The unit highlights the interaction between manage-ment accounting and financial accounting, explains the importance of shareholder value and its relationship to organisational strategy and man-agement control, then frames accounting information in its broader context as part of a management control system. Emphasis is placed on the manager’s role in the design of accounting information systems.

Unit 2 considers the use of accounting information in making pricing

decisions, beginning with an introduction to cost behaviour and the distinctions between fixed and variable costs, average and marginal costs. This unit also covers break-even analysis, cost-plus pricing, target rate of return, optimum and special pricing decisions, and segmental profitability analysis.

Unit 3 focuses on how accounting information can be used in

production-volume decisions. It begins by considering operations that follow the pricing function (already covered in Unit 2). The concept of the value chain is considered when contrasting the different operating decisions faced by manufacturing business and service industries. Particular issues covered are production capacity under resource constraints, product mix and relevant costs in relation to the make-versus-buy decision of the whole-saler. Quality management costs and environmental costs are also considered.

Unit 4 explains how accountants have used production volumes to classify

costs and determine the costs of products and services. Various concepts such as direct/indirect costs, cost driver and cost object are introduced, and their importance is explained in terms of the indirect cost allocation problem. After learning about the basic volume-based production costing system, you turn in Units 5 and 6 to examine a more complex, more accurate but more costly production costing system known as activity-based costing. A compari-son is made between activity costs and the Japanese approach to production costing.

The topic of Unit 7 is capital investment decision-making, an important element of long-term strategy implementation. This unit covers the use of accounting rate of return, payback and discounted cash flow techniques in capital investment decisions.

Unit 8 examines in detail the transfer-pricing problem that typically arises

within multi-product and multi-regional organisation studies. The remainder of the unit examines the popular techniques used to evaluate the performance of organisational divisions, branches and units, with a strong focus on budg-etary control. The final section examines the uses of profit budgets and cash forecasts, budget-setting processes and the way budgeting processes are used for cost control.

5 Learning

Outcomes

When you have completed your study of this course, you will be able to:

• discuss the importance of an effective management control system, including a well-designed accounting information system

• identify the relevant costs to consider in marketing and pricing decisions

• plan production volumes and product-line combinations

• make decisions that take account of quality management and environmental costs

• apportion overhead costs to products and services using a range of methods

• apply appropriate capital investment appraisal methods

• explain the ways in which divisional performance might be measured

• design an effective budget-setting process to help control a business.

6 Study

Materials

This study guide is your main learning resource for the course as it directs your study through the eight study units. Each unit includes recommended reading from the nominated textbooks below and from the Course Reader.

Text Books

Paul Collier (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting

Information for Decision-Making, Fourth Edition, Chichester UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Anthony A Atkinson, Robert S Kaplan, Ella M Matsumara, S Mark Young (2012) Management Accounting, Sixth Edition, Harlow UK: Pearson

Education.

Readings

You are provided with a range of academic journal articles, extracts from supplementary texts, articles written by academics and taken from the finan-cial press, and a number of simulation lessons. This material comprises the Readings – an essential part of this course.

7

Teaching and Learning Strategy

As mentioned above, the course uses a range of examples and case studies to illustrate the theoretical principles and assist you to understand and use management accounting information. Review questions and exercises are included in the course to facilitate your learning.

The course is structured around eight units. It is expected that studying each unit, including the recommended readings and activities, will take between 15 and 20 hours per week. However, these timings may vary according to your familiarity with the subject matter and your own study experience. You will

receive feedback through comments on your assignments and there is a specimen examination paper to help you prepare for the final examination.

8 Assessment

Your performance on the course is assessed through two written assignments and one examination. The assignments are written after week four and eight of the course sessions and the examination is written at a local examination centre in October.

The assignment questions contain fairly detailed guidance about what is required. All assignment answers are limited to 2,500 words and are marked using marking guidelines. When you receive your grade it is accompanied by comments on your paper, including advice about how you might improve, and any clarifications about matters you may not have understood. These comments are designed to help you master the subject and to improve your skills as you progress through your programme. The written examinations are ‘unseen’ (you will only see the paper in the exam centre) and written by hand, over a three hour period. We advise that you practice writing exams in these conditions as part of your examination preparation, as it is not something you would normally do. You are not allowed to take in books or notes to the exam room. This means that you need to revise thoroughly in preparation for each exam. This is especially important if you have completed the course in the early part of the year, or in a previous year.

Preparing for Assignments and Exams

There is good advice on preparing for assignments and exams and writing them in Sections 8.2 and 8.3 of Studying at a Distance by Talbot. We recom-mend that you follow this advice.

The examinations you will sit are designed to evaluate your knowledge and skills in the subjects you have studied: they are not designed to trick you. If you have studied the course thoroughly, you will pass the exam.

Understanding assessment questions

Examination and assignment questions are set to test different knowledge and skills. Sometimes a question will contain more than one part, each part testing a different aspect of your skills and knowledge. You need to spot the key words to know what is being asked of you. Here we categorise the types of things that are asked for in assignments and exams, and the words used. All the examples are from CeFiMS examination papers and assignment questions.

Definitions

Some questions mainly require you to show that you have learned some concepts, by setting out their precise meaning. Such questions are likely to be preliminary and be supplemented by more analytical questions. Generally ‘Pass marks’ are awarded if the answer only contains definitions. They will contain words and phrases such as:

Describe Define

Examine Distinguish between Compare Contrast Write notes on Outline What is meant by List Reasoning

Other questions are designed to test your reasoning, by explaining cause and effect. Convincing explanations generally carry additional marks to basic definitions. They will include words and phrases such as:

Interpret

Explain

What conditions influence

What are the consequences of

What are the implications of

Judgment

Others ask you to make a judgment, perhaps of a policy or of a course of action. They will include words and phrases like:

Evaluate

Critically examine

Assess

Do you agree that

To what extent does

Calculation

Sometimes, you are asked to make a calculation, using a specified technique, where the question begins:

Use indifference curve analysis to

Using any economic model you know

Calculate the standard deviation

Test whether

It is most likely that questions that ask you to make a calculation will also ask for an application of the result, or an interpretation.

Advice

Other questions ask you to provide advice in a particular situation. This applies to law questions and to policy papers where advice is asked in relation to a policy problem. Your advice should be based on relevant law, principles, evidence of what actions are likely to be effective.

Advise

Provide advice on

Critique

In many cases the question will include the word ‘critically’. This means that you are expected to look at the question from at least two points of view, offering a critique of each view and your judgment. You are expected to be critical of what you have read. The questions may begin:

Critically analyse

Critically consider

Critically assess

Critically discuss the argument that

Examine by argument

Questions that begin with ‘discuss’ are similar – they ask you to examine by argument, to debate and give reasons for and against a variety of options, for example:

Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of

Discuss this statement

Discuss the view that

Discuss the arguments and debates concerning

The grading scheme

Details of the general definitions of what is expected in order to obtain a particular grade are shown below. Remember: examiners will take account of the fact that examination conditions are less conducive to polished work than the conditions in which you write your assignments. These criteria

are used in grading all assignments and examinations. Note that as the criteria of each grade rises, it accumulates the elements of the grade below.

As-signments awarded better marks will therefore have become comprehensive in both their depth of core skills and advanced skills.

70% and above: Distinction, as for the (60–69%) below plus:

• shows clear evidence of wide and relevant reading and an engagement with the conceptual issues

• develops a sophisticated and intelligent argument

• shows a rigorous use and a sophisticated understanding of relevant source materials, balancing appropriately between factual detail and key theoretical issues. Materials are evaluated directly and their assumptions and arguments challenged and/or appraised

• shows original thinking and a willingness to take risks

60–69%: Merit, as for the (50–59%) below plus:

• shows strong evidence of critical insight and critical thinking

• shows a detailed understanding of the major factual and/or theoretical issues and directly engages with the relevant literature on the topic

• develops a focussed and clear argument and articulates clearly and convincingly a sustained train of logical thought

• shows clear evidence of planning and appropriate choice of sources and methodology

50–59%: Pass below Merit (50% = pass mark)

• shows a reasonable understanding of the major factual and/or theoretical issues involved

• shows evidence of planning and selection from appropriate sources,

• demonstrates some knowledge of the literature

• the text shows, in places, examples of a clear train of thought or argument

• the text is introduced and concludes appropriately

45–49%: Marginal Failure

• shows some awareness and understanding of the factual or theoretical issues, but with little development

• misunderstandings are evident

• shows some evidence of planning, although irrelevant/unrelated material or arguments are included

0–44%: Clear Failure

• fails to answer the question or to develop an argument that relates to the question set

• does not engage with the relevant literature or demonstrate a knowledge of the key issues

• contains clear conceptual or factual errors or misunderstandings

[approved by Faculty Learning and Teaching Committee November 2006]

Specimen exam paper

Your final examination will be very similar to the Specimen Exam Paper that appears at the end of this introduction. It will have the same structure and style as the actual exam, and the range of questions will be comparable. CeFiMS does not provide past papers or model answers to papers. Our

courses are continuously updated, and past papers will not be a reliable guide to current and future examinations. The specimen exam paper is designed to be relevant and to reflect the exam that will be set on the current edition of the course.

Further information

The OSC will have documentation and information on each year’s examin-ation registrexamin-ation and administrexamin-ation process. If you still have questions, both academics and administrators are available to answer queries.

The Regulations are available at www.cefims.ac.uk/regulations.shtml, setting out the rules by which exams are governed.

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON

C

ENTRE FORF

INANCIAL ANDM

ANAGEMENTS

TUDIESMSc Examination

for External Students 91DFM C370

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

Management

Accounting

Specimen Examination

This is a specimen examination paper designed to show you the type of examination you will have at the end of this course. The number of questions and the structure of the examination will be the same, but the wording and requirements of each question will be different.

The examination must be completed in THREE hours.

Answer THREE questions, selecting at least ONE question from EACH section. The examiners give equal weight to each question; therefore, you are advised to distribute your time approximately equally between three ques-tions.

DO NOT REMOVE THIS PAPER FROM THE EXAMINATION ROOM. IT MUST BE ATTACHED TO YOUR ANSWER BOOK AT

THE END OF THE EXAMINATION.

PLEASE TURN OVER

SECTION A

Answer at least one question from this section. QUESTION 1.

You are the financial manager of the Television division of a manufacturing company that makes energy saving devices. Its principal customers are retailers in the electrical goods market. You have been asked by the produc-tion director to provide advice on the operaproduc-tions of the new Ecofriendly Television production line.

The Television division produces only one line of Ecofriendly Television sets but has a long-term contract with a major retailing chain to sell 10,000

Ecofriendly Television sets each month. The following data are available.

£

Sales price per unit 500.00

Variable costs per unit:

Direct material 100.00

Direct labour and on-costs 100.00

Variable support 100.00

Fixed costs per unit 100.00

Total unit costs 400.00

Production occurs in batches of 20 units.

Each batch takes 2 machine hours to manufacture. Machine hour capacity is 1,000 hours.

Required:

a Determine the profitability of the Ecofriendly Television

produc-tion line and advise the producproduc-tion executive director as to the

production decision. (50 marks)

b The following information is available for the Television division

for the previous month.

Actual amounts

Materials: 5 000 pounds purchased at £12.00 per pound; used 6 000 pounds Direct labour: 5 000 hours at £10.00 per hour

Units produced: 2,000

Standard amounts

Materials: 5 pounds per unit at a price of £10.00 per pound

Labour: 30 minutes per television set at a wage rate of £10.00 per hour

Determine the price and quantity variances of materials and labour used in production. Comment on the relationships

QUESTION 2.

Fleeting Image Ltd is considering the option of replacing the commercial carrier it currently uses for its customer deliveries with an investment in a fleet of ten delivery vans.

It is expected that Fleeting Image Ltd’s existing carrier will charge a total of £200,000 each year for the next three years to undertake the deliveries.

The new vans would cost £30,000 each to buy, payable immedi-ately. The annual running costs are expected to total £10,000 for each van (including the driver’s salary).

The new vans would be expected to operate successfully for three years, at the end of which period they would have to be scrapped, with zero expected disposal proceeds.

The average rate of taxation of corporate income for Fleeting Image Ltd has been 10 percent. This rate also holds for any capi-tal gains. The depreciation rate allowable for taxation purposes is 40 percent reducing balance. The cost of capital for Fleeting Image Ltd is estimated at 10 percent.

a What is the expected accounting rate of return if the fleet of

motor vehicles is purchased? (20 marks)

b What is the expected payback period if the fleet of motor vehicles

is purchased? (20 marks)

c Advise on the relative advantages and limitations of the

account-ing rate of return and payback period methods of project evaluation. Discuss the mechanics, strengths and assumptions used in discounted cashflows evaluation. Provide a calculation

based on a discounted cashflow method of your choice. (60 marks)

QUESTION 3.

A nursing home located inside a large district hospital has been examining its budgetary control procedures with reference to its support costs. 6,000 patients are expected from the budget period. In the first six months of the year, costs were incurred evenly and the same expectation is held for months 7 to 12.

During months 1 to 6, the total number of patients treated were 2,700 and actual support costs are as follows:

Expense £ Staff 59 400 Utilities 27 000 Supplies 54 000 Other 8 100 Total 148 500

Fixed costs are budgeted for the entire year as follows:

Expense £

Supervision 120 000

Depreciation and financing 187 200

Other 64 800

Total 372 000

a Present a support costs budget for months 7 to 12 of the year.

You should show each expense but should not separate

individ-ual months. What is the total support cost for each patient? (60 marks)

b During months 7 to 12 the nursing home treated 3,800 patients,

support costs were £203,300 and fixed costs amounted to £190,000. Comment on the financial performance of the nursing home in this period. Show all calculations and describe any

as-sumptions used in your analysis. (40 marks)

QUESTION 4.

a Explain why transfer prices are used between divisions of an

organization where each trading division is appraised using

profit performance. (40 marks)

b Identify the consideration in choosing a transfer pricing method

to be used under the following conditions:

i the product being transferred has an outside market and the producing division is working at full capacity making sev-eral different products.

ii the product being transferred has an outside market and the

producing division has spare capacity.

iii a product is produced using parts from different production

centres none of which has an external market for their work

except the centre completing the final product. (60 marks)

SECTION B

Answer at least one question from this section. QUESTION 5.

A group of operations executives has asked you to explain the steps involved in determining activity cost driver rates in an activity-based costing system. They have also asked you to de-sign such a system for a particular production problem

involving its two main product lines. One line consists of rela-tively low-cost, stackable, plastic furniture, designed for outdoor use. The other product line is a number of models of ergonomically designed office chairs, designed for executives’ and directors’ offices.

Briefly outline to the group what you understand by a cost driver and outline the steps involved in determining activity cost driver

rates in an activity-based cost system. Your answer should out-line how activity-based cost systems can overcome the

weaknesses of other types of cost allocation systems and at the same time might lead to new strategic concerns.

QUESTION 6.

How can analysis of variances between budgeted and actual production costs assist in the achievement of a company’s stra-tegic objectives?

QUESTION 7.

In capital budgeting, what is Economic Value Added, what data is needed when computing Economic Value Added, and what useful information can Economic Value Added provide? Do you consider Economic Value Added to be superior or inferior to other methods of project evaluation? Explain why or why not. Provide examples to support your argument.

QUESTION 8.

Your Finance Director has been reading about environmental costs and the treatment of carbon emissions. You have been asked to prepare a brief to the board on the relevance of envi-ronmental costs, whether envienvi-ronmental costs should be included in the management accounts, and any strategic con-siderations that might be relevant for the board.

Prepare a brief as required. Use any of the theories covered in the course in providing an evaluation of environmental costing in terms of strategic cost management. Provide examples of mandatory and voluntary costing standards, where appropriate.

Unit 1 The Context of Management

Accounting

Contents

1.1

Introduction to Management Accounting 3 1.2 Shareholder Value and Management Control Systems 4 1.3 Non-financial Accounting Information 111.4

Summary and Practice Tasks 121.5

Case Study 14Unit Overview

Unit 1 sets the scene for the course by defining and explaining key terms used in management accounting and control. The unit first describes the need for firms to produce management accounting information, then explains account-ing information as part of a management control system designed to address financial and operational risks faced by firms. Understanding management accounting as a way to control risk is crucial for the rest of the course. In later units you will look in more detail at specific elements of management ac-counting techniques and information.

Key terms that you should be able to define and discuss are these: Manage-ment control, Risk manageManage-ment, Accountability, Internal controls,

Shareholder value, Cybernetics, Entropy, Business cycles, Corporate govern-ance, Balanced scorecard, Stakeholder reporting, Performance measures.

Learning Objectives

When you have completed your study of this unit, including the recom-mended readings and activities, you will be able to

• discuss the key qualities that management accounting information should possess

• compare and contrast financial accounting and management accounting

• assess management information from a corporate governance perspective, a shareholder value perspective and a stakeholder perspective

• evaluate the design of an internal control system over a company’s business cycles

• describe, using flowcharting terminology and in words, the various processes in revenue and expenditure business cycles, and use that work to evaluate how a company controls its accounting information

• describe how companies can combine non-financial and financial performance measures using metrics such as the balanced scorecard.

Reading for Unit 1

Textbooks

Paul Collier (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting Information for Decision-Making, Chapter 1 ‘Introduction to Accounting’, Chapter 2 ‘Accounting and its Relationship to Shareholder Value and Corporate Governance’, and extracts from Chapters 4, 5 and 9.

Anthony Atkinson, Robert Kaplan, Ella Matsumara and Mark Young (2012) Management Accounting, sections from Chapter 1 ‘How Management

Accounting Information Supports Decision Making’, and Chapter 2 ‘The Balanced Scorecard and Strategy Map’.

Course Reader

Ruth Hines (1988) ‘Financial Accounting: In Communicating Reality, We Construct Reality’.

1.1 Introduction to Management Accounting

In this course you will study management accounting in a variety of in-dustries, contexts and countries. Before this, though, it is essential that you understand what management accounting actually is and what the manage-ment accounting function means to an organisation.

Putting management accounting information in organisational context, firms are required to produce financial reports, which are regulated by

gov-ernmental agencies. Management accounting information, however, is not mandated by law (although there is a legal requirement for businesses to keep proper accounting records). Even though there is no direct legal mandate for management accounting reports, corporate governance requirements im-posed on large businesses compel businesses to report how they conduct their operations and manage a wide variety of operational and strategic risks. These aspects of risk management are called internal controls; in some count-ries such as the United States, businesses report on their internal controls to regulators and shareholders.

How are internal controls over management accounting information related to corporate governance? Unmonitored controls tend to deteriorate over time. Monitoring by managers is implemented to help ensure that internal control continues to operate effectively. When monitoring is designed and imple-mented appropriately, organisations benefit because they are more likely to:

• identify and correct internal control problems on a timely basis

• produce more accurate and reliable information for use in decision-making

• be in a position to provide periodic certifications or assertions on the effectiveness of internal control.

ReadingsPlease turn to your textbook by Paul Collier, and study Chapter 1 – the sections ‘Account-ing, accountability and the account’ and ‘Introducing the functions of accounting’. Also read from Atkinson and his colleagues’ Chapter 1, pages 25 to 28, ending with the section ‘IN PRACTICE: Definition of Management Accounting.

These two readings provide an overview of what accountancy is and introduces manage-ment accounting information for internal users such as company directors, managers and employees. It is the use of management accounting for people inside an organization that is the focus of this course.

ExerciseAs you work through the two readings above, try to suggest reasons why management accounting information is needed. Also, note the similarities and differences in the various definitions of accounting in Collier and Atkinson et al.

Financial reporting is based on third-party accountability – that is, on representations made by managers to external claimants on the firm such as shareholders, tax authorities and creditors. Furthermore, corporate law requires financial reports to be prepared by manag-ers which, on behalf of a firm’s external claimants, are reviewed by ‘external’ auditors.

Paul Collier (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting Information for Decision-Making, Chapter 1 ‘Introduction to Accounting’; and Anthony Atkinson, Robert Kaplan, Ella Matsumara and Mark Young (2012) Management Accounting, Chapter 1 ‘How Management Accounting Information Supports Decision Making’: sections cited.

Look at the section in Collier’s Chapter 1 called ‘Accounting, accountability and the account’, compare and contrast external financial reports to the types of human resources information, production information and financial information needed within an organisation.

In the exercise above, you may have come up with a range of suggestions on why management accounting information is needed, such as to support decision-making and to provide performance benchmarks of divisions within companies. Although there are strong arguments for producing management accounting information for internal performance, there are also arguments against producing management accounting information. We will come across some of these arguments later in Unit 8 when we study budgeting.

Now that you have an understanding of management accounting informa-tion, it’s time to consider the two broad types of accounting activities. The key difference between management accounting and financial accounting is one of focus.

• Management accounting is focused on internal uses, such as producing information for use in cost budgets, labour hiring plans, and sales forecasts.

• Financial accounting is focused on external uses, such as producing information that meets the demands of tax authorities, stock exchanges, lenders and shareholders for information on the assets and liabilities of a business.

ReadingPlease turn to Collier’s Chapter 1 and read the following three sections: ‘The role of financial accounting’; ‘The role of management accounting’; and ‘The relationship between financial accounting and management accounting’.

As you study these sections, make notes of the key differences between financial accounting and management accounting, paying attention to their objectives, organisa-tional functions, and actual information items produced.1.2 Shareholder

Value

and

Management

Control

Systems

Before we move on to study management accounting information, it is useful to study its organisational context. Management control in profit-oriented businesses adopts the perspective that shareholder value is the most import-ant objective of the management of a business. Management is held to account by shareholders. In the case of profit-oriented businesses, the single organiza-tional objective to which managers are held to account is usually held to be wealth maximisation. In the case of non-profit organisations, organisational objectives are the execution of specific operational programs and the

achievement of specific outcomes, which may differ from organisation to organisation, and may or may not include financial objectives.

We understand accounting information systems as a subset of management control systems. Managers need to understand accounting information

Paul Collier (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting Information for Decision-Making, Chapter 1 ‘Introduction to Accounting’: sections cited.

systems (hereafter, AIS) if they are to control the variety of risks associated with running an organisation. The operational benefits of an effective AIS are:

1 effective decision-making, and

2 acceptable standards of customer service, product and service quality, productivity, and cost of production.

Other benefits of an effective AIS, and relevant to a shareholder value per-spective on the firm, are:

3 quality information in external financial statements, such as balance sheets, and internal financial statements, such as divisional operational budgets, and

4 good corporate governance, meaning that a company is well-controlled, being aware of and having taken measures to counter risks arising in its ordinary course of business.

The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants does not define an internal control of itself but defines an internal control system. A system of internal controls is the whole system of controls, financial and non-financial, established in an effort to provide managers reasonable assurance that busi-ness operations are effective and efficient, that the firm is well-controlled financially and that the firm complies with relevant laws and regulations.

ReadingPlease turn to Collier’s Chapter 2 and read the section ‘Shareholder value-based manage-ment.’

Make notes of the types of data used in operational performance measures, and compare that with the types of data used in financial performance measures.You do not need to study all the various types of financial ratios – instead, note the type of data that are being used in these ratios. All this data is produced by accounting informa-tion systems, and it is to those that we now turn.

1.2.1

The internal control system

The section in Collier’s Chapter 4 ‘Planning and control in organizations’ (which you will be studying in the next sub-section) introduces a cybernetic approach to business systems. A cybernetic approach takes a view that business operations will collapse over time unless systemic faults are diag-nosed and corrected.

The ‘first-order’ cybernetic approach views business operations as subject to entropy, or the tendency of a system to disintegrate over time. Management controls are seen as part of a feedback loop that generates negative entropy – that is, that identifies ‘noise’ in the operational system or information system, and deals with that noise by neutralising its effects, a reaction which allows systems to remain functioning as designed. (So-called ‘second-order’ cyber-netic systems, by contrast, identify noise in the system but do not eradicate it. Instead, second-order systems incorporate unintended noise in the system.)

Paul Collier (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting Information for Decision-Making, Chapter 2 ‘Accounting and its Relationship to Shareholder Value and Corporate Governance’: section cited.

a) a control environment which exists at the whole-of-firm level

b) internal controls that are introduced and maintained over a company’s operational and informational processes.

A control environment describes senior management’s and the board of direc-tors’ attitude towards controls. Establishing a foundation for monitoring controls means to institute a proper ‘tone at the top’. A strong control envi-ronment will institute an organisational structure that assigns monitoring roles to people with appropriate capabilities, objectivity and authority. On the other hand, if the control environment in an organisation is weak, then

internal controls in that organisation are also likely to be ineffective.

No matter how well the internal controls are designed, they can only provide a reasonable assurance that objectives will be achieved. Some limitations are inherent in all internal control systems. These limitations include:

• Judgment – the effectiveness of controls will be limited by decisions made with human judgment under pressures to conduct business based on the information available at hand.

• Breakdowns – even well designed internal controls can break down. Employees sometimes misunderstand instructions or simply make mistakes. Errors may also result from new technology and the complexity of computerised information systems.

• Management Override – high-level personnel may be able to override prescribed policies or procedures for personal gains or advantages. This should not be confused with management intervention, which represents management actions to depart from prescribed policies and procedures for legitimate purposes.

• Collusion – control system can be circumvented by employee collusion. Individuals acting collectively can alter financial data or other

management information in a manner that cannot be identified by control systems.

In the presence on a weak control environment, any or all of the limitations can be expected to exist in an organization.

Internal controls are specific to business processes and operate on various levels. Effective internal controls enable the proper functioning of business processes – e.g. sales-ordering, warehouse management, shipping goods to customers, ordering goods from suppliers and so on.

The objectives of internal controls over a specific business process are: 1 Authorisation

2 Completeness 3 Accuracy 4 Validity

5 Physical safeguards and security 6 Error handling

According to the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations, internal controls can be categorised according to whether internal controls are detective, corrective or preventive 1.

1 Detective controls are designed to detect errors or irregularities that may have occurred in operational processes and/or in information flows. 2 Corrective controls are designed to correct identified errors or irregularities

in operational processes and/or information flows.

3 Preventive controls are designed to keep errors or irregularities in operational processes and/or information flows from occurring in the first place.

There are many controls available, some of which are indispensable and necessary, and others that are less necessary. A key control is one that in its absence would lead to the system breaking down. A key control can be detective, corrective or preventive.

The systems-based approach to controlling business cycles relies on the ability of a business to control its strategy-setting, operational and reporting systems. Managing a firm means to

a) the control environment that exists at the whole-of-firm level and b) the internal controls maintained over a company’s operational and

informational processes.

ExampleRisk: Sales staff are responsible for creating sales orders from business customers, for approving sales orders, and for receiving cheque payments from customers. The lack of segregation of the execution function (sales), the authority function (approval) and the custody function (handling cheques) may mean that it is now possible for sales staff to create a fictitious vendor or change existing vendor master data and approve purchases to that fictitious or altered vendor name.

Appropriate control to mitigate this risk: Segregate the execution, authority and custody functions in the sales ordering process. This means a different person should perform each function. If the company is so small that three people are not available for these functions, then the company can institute a mitigating control such as financial controller review or internal auditor review of sales orders (on a frequent basis but without prior notification to the sales staff).

1.2.2

Business

cycles

An effective understanding of internal controls and an appreciation of their relationship to management accounting information depend on an under-standing of the inter-relationships of business cycles. The two basic business cycles are revenue (or ‘sales’) and expenditure.

1

The four basic business operations within the revenue cycle are Sales, Accounts receivable, Cash receipts, and General ledger processing. Each of these operations is made up of a number of processes.

The expenditure cycle consists of the following basic business operations: Purchases, Accounts Payable, Cash Disbursements, and General Ledger Processing. Similarly, each of those four operations comprises several processes.

Each operation is managed by implementing system controls.

For example, in the Sales operation in the revenue cycle, you may notice that a key control is separating the sales force from the accounts receivable function. A business does not want its sales people to be responsible for chasing its customers to pay their accounts. Why not? If a sales person were to be made responsible for collecting debts owed by customers, it would be possible for the sales person to cancel the record of sales, so the company’s financial controller is never made aware that the sales took place. If the sales person were then to keep the cash receipts collected from customers, using it for her/his own purposes, no one would be able to detect the theft. Putting different people in the accounts receivable and sales functions ensures that this cannot occur – at least, not easily. We can call a functional separation of duties a “segregation of duties”.

While segregation of duties is a preventive control, it is also important to design appropriate detective controls. For example, in the revenue cycle, monthly sales records should be reconciled to debtors’ records. The monthly sales ledger/debtors’ ledger reconciliation is an example of a detective control because it will detect any anomalies between credit sales and cash receipts from credit sales.

Managing these sorts of risks is crucial to any organisation, which is why it becomes important to understand the basic business cycles and the key control that a business will rely on to manage its operations.

Readings on Business CyclesFirst, study the sections in Collier’s Chapter 9 ‘Business processes’ and ‘Internal controls for information systems’. These two sections explain internal controls in terms of two basic business processes: the revenue business cycle (or cash in), and the expenditure business cycle (or cash out).

When you have read that section, please turn to this textbook’s Chapter 4 and read the sections ‘Management control systems’ and ‘Planning and control in organizations’.

As you read these sections, make notes on the importance of internal controls for management decisions concerning manufacturing decisions and marketing decisions. Exercises on business cyclesYou have already learned from above that a key control is one that in its absence would lead to the business process breaking down.

Exercise 1 Nominate at least one key control in the following sub-cycles: Sales, Accounts Receivable, Cash Receipts, and General Ledger Processing.

Paul Collier (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting Information for Decision-Making, Chapter 9 ‘Accounting and Information Systems’, and Chapter 4 ‘Management Control, Accounting and its Rational-Economic

Assumptions’: sections cited.

Exercise 2 Re-read Collier’s Chapter 9 ‘Business processes’ and ‘Internal controls for information systems’, noting the key internal controls over the expenditure busi-ness cycle. Nominate at least one key control in the sub-cycles of Purchases, Accounts Payable, Cash Disbursements, and General Ledger Processing.

Figure 1.1 Identifying Key Controls –Some useful symbols to start with. Customer purchase order or sales order Packing slip / pick ticket Sales invoice Monthly statement Bill of lading Back order information Turnaround document (or remittance advice)

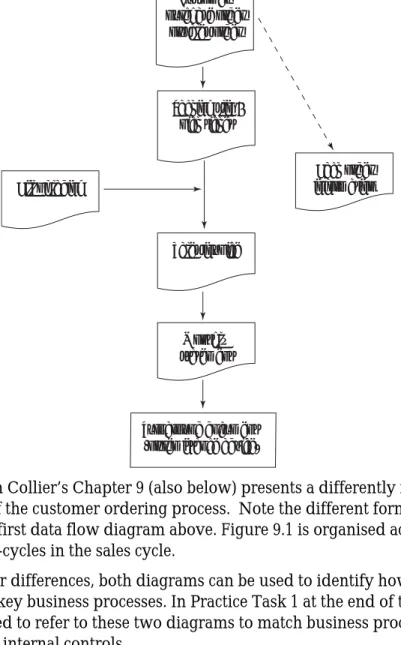

Figure 9.1 in Collier’s Chapter 9 (also below) presents a differently formatted flowchart of the customer ordering process. Note the different format to that used in the first data flow diagram above. Figure 9.1 is organised according to the five sub-cycles in the sales cycle.

Despite their differences, both diagrams can be used to identify how a firm controls its key business processes. In Practice Task 1 at the end of this unit, you will need to refer to these two diagrams to match business processes with appropriate internal controls.

Figure 9.1 (Collier’s Chapter 9, p.175) Customer Order Processing Customer order received Packing slip Signed delivery note Data entry of order Check stock levels Goods taken from shelf Goods assembled for order Picking slip updated Inventory record updated Transport schedule Goods delivered to customer Sales analysis updated accounts recievable

updated Invoicing Invoice to customer Signed delivery note A CCOUNTING TRANSPOR T WAREHOUSE SALES ORDER PROCESSING Source: Collier (2012)

1.2.3

Alternative perspectives: stakeholder analysis

One criticism of the dominant concern with shareholder value is that it directs attention away from the accountability obligations that profit-oriented firms may owe to the wider society. We can say that those parties and groups that are affected by or who have influence in organisations are ‘stakeholders’. Stakeholder groups have stakes, even if they are non-financial stakes, in organisations.

For example, if a recreation area for a neighbourhood’s common use is pur-chased by a business which plans to develop it commercially, the

neighbourhood becomes a stakeholder of that business, even though none of the residents may be shareholders. The neighbourhood might want the business to report how it will manage the desires of the neighbourhood for a common-use recreation area.

ReadingsFirst, please turn to Collier’s Chapter 2 and read the section ‘A critical perspective’.

As you study this section, make notes on how corporate governance requirements refer to the shareholder value concept.Now turn to Collier’s Chapter 5 and read the introduction and the sections ‘Research and theory in management control and accounting’ and ‘Culture, control and accounting’.

As you work through these readings, make notes on: a) the normative view of accounting research b) the interpretive view of accounting research c) the critical view of accounting research.Paul Collier (2012)

Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting Information for Decision-Making, Chapter 2 ‘Accounting and its Relationship to Shareholder Value and Corporate Governance’: section ‘A critical perspective’ and Chapter 5 ‘Interpretive and Critical Perspectives on Accounting and Decision Making’.

You will find the notes you make here a useful reference for the rest of the unit (especially the case studies at the ends of the units). Paul Collier’s textbook examines management accounting using these three perspectives, and the remaining units in this course also ask you to evaluate management accounting techniques and management accounting informa-tion according to each of these perspectives.

ReadingsYour course reader contains a short article ‘Financial Accounting: In Communicating Reality, We Construct Reality’, by Ruth Hines. Read this article, adding to the notes you have already started in this unit on shareholder value. Although this article is about financial accounting, its insights are also relevant for management accounting information. The article argues that the provision of accounting information itself can influence the behaviours of individuals and companies. This insight allows us to consider and asses the types of behaviour promoted by shareholder value, and compare that to the type of behaviour promoted by stakeholder theory.

1.3 Non-financial

Accounting

Information

Financial measures of performance are often the easiest to measure; at their simplest, profit (or economic surplus) equals income minus expenses. Finan-cial measures tend to be the ones that are focused on most by managers. However, purely financial measures do not always reflect other factors that are critical to the success of a business.

One of the methods used by organisations to combine financial and non-financial measures is the balanced scorecard, developed by Robert Kaplan, one of the authors of your textbook, Management Accounting.

The four areas that balanced scorecards often measure are represented in a 2 x 2 grid, as shown below. The idea of the grid arrangement is that the four corners are ‘balanced’ in terms of importance:

Financial measures Customer/client measures

Internal business process measures Learning and growth measures

Also refer to Collier’s Figure 4.5, and Exhibit 2-4 in Atkinson et al. Note the variations in the titles used in the boxes above.

In many organisations that use balanced scorecards, the performance rubrics chosen reflect the organisation’s profile, mission and specific objectives. For example, Arup, a leading international engineering group and very dependent on their professional staff and the organisation’s design skills, has modified ‘Internal business process measures’ in the box above as ‘Design process measures’, and ‘Learning and growth measures’ has been modified to

Ruth Hines (1988) ‘Financial Accounting: In Communicating Reality, We Construct Reality’, reprinted in the Course Reader from

Accounting, Organizations and Society.

Please read the following three sections from your textbooks: Collier’s Chapter 4 ‘Non-financial performance measurement’; Atkinson et al. Chapter 2, ‘The Balanced Scorecard’ pp. 43–47; and

Atkinson et al. Chapter 2 ‘Strategy Map and balance Scorecard at Pioneer Petroleum’ pp. 60–66.

ExerciseDescribe the strengths and weaknesses of using non-financial performance measurement systems at Pioneer Petroleum.

Consider the firm’s stakeholders, e.g. different employee groups; different locations of customer groups; multi-party suppliers; international logistics operations; and operating in multiple legal jurisdictions – e.g. Asia and Europe.

Note the areas of operations that Pioneer Petroleum declares are important. Clue: identify the areas that the company declares are risky.

Are there any operational areas that Pioneer Petroleum has not mentioned? Where that is the case, why do you think this has occurred?

Note the performance measures that Pioneer Petroleum uses for each operational area.

1.4 Summary

and

Practice

Tasks

This unit has been about setting the scene before you go on to study the specifics of management accounting in more detail in the rest of this course. In Section 1.1, you studied how accountability has produced demands for both financial and management accounting information. The accountability de-mands for management accounting information come from various levels of managers in a firm.

The table below may help you understand the difference between the two main strands of accounting:

Management accounting Financial accounting

Also known as Management information Statutory accounts, financial statements, annual accounts, annual returns

Main users Internal users such as managers

External users such as investors, lenders, suppliers, tax

authorities

Information provided and format of this information

Decided by management to best suit the business’s requirements

Set down by legislation and regulations

Detail provided Considerable detail Broad overview

Reporting frequency As frequently as required: daily, weekly, monthly

Annual, and quarterly or half-yearly for large businesses

Time horizon Past and future periods (forecasts)

Past periods (backwards-looking) Paul Collier (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting Information for Decision-Making, Chapter 4 ‘Management Control, Accounting and its Rational-Economic Assumptions’; and Anthony Atkinson, Robert Kaplan, Ella Matsumara and Mark Young (2012)

Management Accounting Chapter 2 ‘The Balanced Scorecard and Strategy Map’: sections cited.

Audit and tax Not used for external audit or taxation authorities. May be used for internal audit purposes

Often audited and used for tax calculations

In Section 1.2, you learned how accountability demands for management accounting information also come from governance requirements imposed by regulators and stock exchanges. You also studied how shareholders’ interests dominate reporting requirements imposed on businesses. You have seen arguments for and against managing a business according to the shareholder-value concept.

Stakeholder theory is an attempt to consider management accounting infor-mation in terms of its social implications. Stakeholder reporting attempts to redress the information needs of parties outside the narrow remit of creditors and shareholders.

Organisational control is achieved primarily through the design of internal control systems. Accounting information is important because it helps a business control its strategies and operational risks, as well as meeting the demands of shareholders. In Section 1.3, you studied non-financial perform-ance measurement. The Balperform-anced Scorecard provides a way that a business can ensure it balances its financial performance measures with other types of performance measures. Putting the distinction between financial and non-financial accountability to one side, the perspective found most often in management control, and reflected in professional bodies such as The Com-mittee of Sponsoring Organizations, is a rational, goal orientation. Reflecting that, the effectiveness of management control systems is often gauged using a systems-based approach which detects weakness in system controls.

Practice TasksAttempt any two (2) of the following four practice tasks as a way to refresh your understanding of this unit before you move on to the case study below.

Practice Task 1

i) Using the two data-flow diagrams above in Section 1.2, identify which of the vari-ous processes in the sales process are most important to a company.

ii) How will managers control the principal processes in sales?

iii) What’s the next business process after the remittance advice is sent to the cus-tomer?

iv) Match each business process (there are eleven listed, i-xi) to the appropriate con-trol (there are eight listed, A-H). Please note that a single concon-trol may be applied to more than one business process.

Business processes

i. Customer Sale. ii. Send goods to shop. iii. Inquire inventory. iv. Need more goods.

vi. Raise a purchase order. vii. Pay suppliers in cheque run. viii. Goods arrive to warehouse. ix. Supplier sends invoice.

x. Send ordered goods to shop or to customer directly. xi. Receive cash from retail customer else send account.

Controls

A. Check customer exists and credit limit. B. Check goods in stock.

C. Obtain approval.

D. Produce despatch note, copy of invoice, and receiving report. E. Put ordered goods aside.

F. Match invoice to receiving report.

G. Review, chase and receive cash from debtors. H. Obtain approval and post to general ledger.

Practice Task 2. Atkinson et al. Chapter 2, Exercise 2-34 p. 75: ‘Balanced scorecard measures, environmental and safety dimensions’.

Practice Task 3. Atkinson et al. Chapter 2, Problem 2-44 p. 76: ‘University balanced scorecard’.

Practice Task 4. Find out if your own organisation or an organisation you are interested in uses the balanced scorecard. Makes notes on the following:

a. the areas of operations that are being assessed

b. the measures the organisation uses to asses operational areas c. the target groups of readers for this information

d. match readers’ presumed informational needs with the actual information that is disclosed. How well do you think that readers’ informational needs are being met?

1.5 Case

Study

The case study for this unit is Collier’s Chapter 5 Case study 5.1: easyJet, pages 71 to 73. Once you have read this case, write a management memorandum of approximately 500 words that, first, describes easyJet’s financial and operational strategies; then evalu-ates easyJet’s management control system.- Use Figure 9.1 in Collier’s Chapter 9 as a guide to draw and explain a data flow diagram (also called a flowchart) of easyJet’s customer order processes, cash re-ceipting and related accounting processes.

- Your evaluation should identify the key controls in easyJet’s revenue cycle. (Key controls are those that if they were absent, the operation would break down.) In-clude at least one key preventive control and one key detective control in customer ordering, cash receipting, and related accounting processes. When writing up this case, you may wish to refer to the website

http://corporate.easyjet.com/investors.aspx. Paul Collier (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting Information for Decision-Making, Chapter 5 ‘Interpretive and Critical Perspectives on Accounting and Decision Making’, Case study 5.1.

References and Websites

Atkinson Anthony, Robert Kaplan, Ella Matsumara and Mark Young (2012) Management Accounting, Harlow Essex UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Collier Paul (2012) Accounting For Managers: Interpreting Accounting

Information for Decision-Making, Fourth Edition, Chichester UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Hines Ruth (1988) ‘Financial Accounting: In Communicating Reality, We Construct Reality’, Accounting, Organizations and Society 13(3): 251–61.

Business Cycles

easyJet, http://corporate.easyjet.com/investors.aspx.

OBA, IOCM and their impact on supplier relationship satisfaction,

http://www.fm-magazine.com/feature/depth/oba-iocm-and-their-impact-supplier-relationship-satisfaction.

Internal Controls

Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, www.cimaglobal.com.

The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO)

http://www.coso.org/documents/COSO_Guidance_On_Monitoring_Intr o_online1_002.pdf.

The Institute of Risk Management,

http://www.theirm.org/aboutheirm/ABaboutus.htm.

Risky Business, http://www.fm-magazine.com/feature/depth/risky-business.