Time of Adjustment: Estimating

Immigrant Integration and Integrative

Capacity of the Finnish Labor Market in

the Long-Term Perspective

OXANA KRUTOVA

1University of Tampere, Finland

TAPIO NUMMI

University of Tampere, FinlandAbstract

This paper examines the integrative capacity of the Finnish labor market as regards immigrant integration in the long-term perspective. In this paper, we study the duration patterns of unemployment and the delong-terminants of transitions out of unemployment spells into employment and other exit states. We also look at, how micro-level determinants of unemployment, when estimated by age, gender, education, and previous experience of unemployment, affect the outcome of transitions out of unemployment spells. The novelty of this research lies in the multidimensional analysis of labor market integration using data and statistical methods that enable to determine the dynamics of status transitions over time. Methodologically, this research has a dualistic ‘descriptive-dynamic’ understanding of labor market integration as a process that is conditioned by a time period of long-term involvement into the labor market. According to our results, transitions to employment have a periodic wavelike character and, in time, the probability for job placement to one of the forms of employment essentially decreases. We also find that the period-effect potentially predict the further labor market integration of immigrants.

Keywords: Labor Market Integration; Integrative Capacity of the Labor Market; Discrete-Time Hazard Models; Duration of Unemployment; Labor Market Transitions.

Introduction

Parallel to developments in transnationalism and the restructuring of the welfare state in Europe since the 1960s, Finland experienced the restructuring of the welfare state and a gradual transition from a regime of accumulation to a regime of decentralizing regional policies with an emphasis on economic growth and competition. The concept of centralized state planning had been developed in the 1950s; however, only since the 1960s has the nation-state undertaken to create a new regulation of economic activities in the peripheries and the creation of a balanced structure with full employment in the regions. Ultimately, the development of the Finnish model of the welfare state has become more spatial and connected to the notions of strategy, security, a coherent nation, and societal order.

As immigration flows intensified form year to year, unemployment became a major threat to societal order and economic growth, especially in areas that were more vulnerable to unstable economic development. The economic recession in the 1960s thus created an incentive to revise the employment policy in Finland. For example, the number of participants in employment

policy measures quadrupled during the two recessions in 1973–75 and 1977–80, when the focus of Finnish active labor market policy was shifted towards selective employment measures. Already in the 1980s, Finland had become one of a few European countries with rather low unemployment rates and active labor market policies. Like many European countries at the beginning of the 1990s, the national economy of Finland fell into a period of economic stagnation. In this period, labor market institutions, which had been effective in previous years, proved to be ineffective as unemployment rates significantly increased. The lowest point of the economic depression had passed by the end of 1992, however, and the government began to restore sustainable economic growth and improve the employment situation.

Until fairly recently, immigration and asylum policy was austerely the preserve of member states in the European Union, and cooperation in this field among the member states has obviously been intensified. Under these conditions, the internal loyalty of citizens was conditioned by the external closure of national borders. In turn, national welfare states undoubtedly conceded the existence of inequality as their inherent feature. On the other hand, international migration was seen as an effort to overcome the existence of inequality. These two dimensions – ‘loyalty’ and ‘provision of the welfare state’ – also represented relations between immigrants and the nation-state, where immigrants could be considered as a potential problem for the nation-state.

During its long period of economic restructuring, Finland has taken steps to create an integration policy that encourages immigrants to find an active role in Finnish society (Pehkonen, 2006). A significant turn in immigration policy took place when Finland became a member of the European Union in 1995. The labor market integration of immigrants and the efficiency of policies became a topical issue as Finland joined the European Union, and also when the European Union extended membership to some eastern European countries in 2004, gradually enabling the free movement of citizens from the new member states (Alho, 2013; Ristikari, 2012).

A country of net emigration up until the 1980s, Finland has had to reconfigure its approach to migration and inclusion in recent decades. The principles acting as the basis of its integration policy promote the integration of immigrants into the labor market and in this way ‘opened up’ the labor market to immigrants. Again, the idea of equal opportunities and access should underpin integration efforts in this sphere by tackling the disadvantages immigrant and minority groups face in entering the workforce (Niessen, Huddleston & Citron, 2007; Sengenberger, 2011).

The employment policy in Finland accentuates on support and assistance in job placement for the unemployed and pays more attention to prevention from earnings’ loss. Employment Services provide unemployed people with various forms of support as preparatory and vocational labor market training, traineeships, etc., however, what do we know about effectiveness of this or that measure on the way to final job placement? Do we know why long-term unemployed population cannot be employed during long time and have even more difficulties in this process, in comparison to ‘ordinary’ unemployed people? How are effectively those, who are being outside the labor market during long time, coming back to the working life? Finally, what factors affect job-placement of immigrants as a more vulnerable group at the labor market? All these questions force to think about existence of tendencies in labor market integration as conditioned by micro- as macro-factors of economic and social development of a host country.

Considering the labor market integration as a dynamic process, the present research focuses on how integrative capacity of the Finnish labor market affects immigrant integration in the long-term perspective. In this paper, we study the determinants of transitions out of unemployment spells into employment and the duration patterns of unemployment. This research aims to define:

• What are the time determinants of transitions out of unemployment spells into other exit states (employment through employment services, employment in the general labor market, employment on a reduced working week, self-employment, labor market training, outside the labor force, another reason or unemployment pension)?

• How does a period, when unemployment occurs affect general dynamics of transitions out of unemployment spells?

In our analysis, we refer to different periods of the historical development of Finland, when substantiating importance of immigration flows and macro factors, which potentially obtain supreme importance especially in periods of economic crises. In light of long history of economic development of Finland, we suppose that flexible policies aim at improving the capacity of the labor market to adapt to its macro-economic environment. Therefore, the scope and frequency of external shocks, which have influenced the world economy, very differently affect flexibility policies at the national or local level. Broadly speaking, a more rapid adjustment of the equilibrium of the labor market to the conditions of the economic environment, which greater flexibility would bring about, improves the economic performance of labor markets. However, any deviation from the principles of flexibility prolongs the period of instability and results in a failure to adapt currency markets to the actual economic conditions of various national entities. We therefore suppose that a period of economic development in many respects predetermines how the labor market allocates the labor force into employment and how effective the processes of labor market integration for immigrants are.

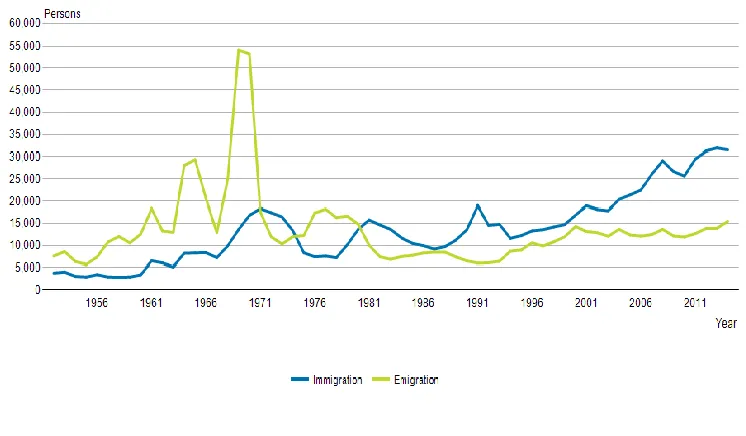

Thus, we analyze the period, when immigration was rare phenomenon in Finland and when emigration exceeded immigration (“1952–1971”), the period, when immigration and emigration are coherently changing (“1972–1991”), and the period, when immigration increased significantly and integration of immigrants becomes one of the most important tasks of the labor market policy (“1992–2014”) (Figure 1). The selected periods differ in terms of labor market trends and policy interventions, what leads us to expect about the prevalence of certain transition modes over others.

Figure 1:Immigration and emigration in Finland in 1952-2014 (numbers of persons by years)

Theoretical background

The integrative capacity of the Finnish labor market

The integrative capacity of the labor market as directed to providing the population more transitions into employment obtains specific characterization in Finland. Modification of the overall economic situation in Finland in a short-term predetermined an overall change of dynamics in the participation of unemployed in employment policy measures. In the context of dynamics of the overall economic situation in Finland in the beginning of the 1990s, a factor of financial support for unemployed people became significant for predetermining processes of job placement among the unemployed. Without bias, participation in employment policy measures decreased risks of recurrent unemployment from 7-11%; however, high unemployment benefits increased risks of recurrent unemployment and negatively influenced participation of the unemployed in employment policy measures (Holm & Tuomala, 1998; Hämäläinen, 1997). Poor indicators of disposal of the unemployed after subsidized employment measures are conditioned by complicated structural characterization of unemployment and, as a result, complicate the influence of employment policy measures to various ”problem” groups in the structure of unemployment (Terävä et al., 2011; Hämäläinen, Tuomala & Ylikännö, 2009; Jolkkonen & Kurvinen, 2012).

Therefore, besides specificity of an employment policy measure and financial support for the unemployed, the third factor as specificity of subjects offering job places in the course of the subsidized employment measures significantly changed overall situation of job placement. One of the significant factors explaining the overall dynamics of job placement among the unemployed is participation in employment policy measures depending on the form of property of enterprises. General tendencies show that job placement in the public sector, as a rule, did not imply long-term employment, whereas job placement in the private sector increased the probability of prolonged job placement and employment. In 11% of cases, the unemployed were not counted in the register of Employment Services because of job placement in the private sector, whereas in the overwhelming majority of cases the unemployed did not appear in the register because of the classification of a small, personally owned enterprise created at the expense of subsidizing public program (Työllistämistukien työllisyysvaikutukset, 2005; Alatalo & Torvi, 2009).

On the other hand, analyzing the tendencies after participation in a subsidized employment measure, one can conclude that in Finland for the period of the 2000s, as in many other countries, around 40% of the unemployed participating in measures have been in unemployment status during three months after a measure has been completed. One of the most important factors of this situation is a high labor demand that also significantly influenced duration of unemployment and probability of transition from an employment policy measure to employment. However, one should consider that official indicators do not allow for concluding the influence of labor market policy as such because some kind of influence can be estimated by means of an empirical research. For example, according to various estimations, a subsidized employment measure is intended mainly for long-term unemployment and what is more important that such a measure in the public sector does not influence final job placement. On the contrary, in the private sector influence from subsidized employment measures are more positive, however, they fluctuate depending on what stage of unemployment an unemployed person is directed to measures and what time-period is used for estimating an effect from a measure. The effect from a subsidized employment measure such as job placement of the unemployed is, without bias, highly dependent on the time of entrance into a measure that is within the first three months of unemployment; with time this effect becomes weaker (Alatalo & Torvi, 2009; Räisänen & Sardar, 2014).

indicator must replace existing indicators of estimation. Without bias, according to the results of various researches, it is obvious that participation in subsidized employment measures only a temporary resolve of a problem, which is not even directed to permanent resolving of job placement for unemployed people. However, if the aim is to support job placement of people in a weak labor market position, one has to accept even the negative sides of such employment. Only a small share of the unemployed who participate in such kind of measures remained in the previous status during the short period, whereas the probability of participation in these measures decreases with time, especially for “long-term” unemployed people (Työllistämistukien työllisyysvaikutukset, 2005).

Time becomes one of the most important factors, explaining the outcomes of integration of the unemployed. According to estimations by the Ministry of Employment and the Economy, as well as the Centre for Economic Development, Transport, and the Environment, the overwhelming majority of salary-based measures continue 6-12 months or more than 1.5 years, whereas on the other hand, measures, which do not base on labor relations continue for 0-6 months (Terävä et al., 2011, p. 45). According to estimations by the National Audit Office, recurrent participation in a measure is typical for unemployed people. A majority of employment policy measures concern unemployed people, who have already participated in them earlier or participate recurrently later. Even though recurrent participation in a measure is emblematic, official estimations of influence from a measure concern predominantly only the first participation. Consequently, it is impossible to estimate the full influence from participation in all measures, as well as the fact that each measure can have influence at the national level as well as at regional labor market level, and can be considered from a position of influence upon participating or not participating in a measure by unemployed people.

Even though a measure would improve opportunities for job placement among unemployed people, the overall influence on the employment sphere can be imperceptible. Often, transitional statements can be critical for future job placement because an unemployed person absent from any measure does not receive the full-value of efficient help needed for faster job placement. In the present system of employment support, an unemployed person spends too much time on waiting for further activities as a part of employment services. If a salary-based measure does not lead to job placement, a passive period of employment support ensues that, in one’s turn, decreases chances for faster job placement (Pitkäaikaistyöttömien työllistyminen, 2011).

When estimating general tendencies, more than 40% of all employment policy measures lasted less than three months. For example, 60% of such measures as traineeship and preparatory labor market training, after which further allocation of unemployed people is weaker than with regards to other measures, lasted less than three months. At the same time, subsidized employment measures, as a rule, are longer (6-12 months). Periods of participation in subsidized employment, which last at least 6 months, increase opportunities for job placement in 15%of cases, whereas shorter periods of subsidized employment lead to employment in only in 8% of cases. These statistical facts are rather important in comparison to this point, that almost half of unemployed people in Finland only end an unemployment period after two years (Työllistämistukien työllisyysvaikutukset, 2005; Peltola, 2005; Tuomala, 1998).

measures and labor market training programs are given more rarely. As practice shows, the longer unemployment lasts and more episodes of unemployment an unemployed person has, consequently, there is less probability to be employed. If a cumulative period of staying in employment policy measures comes to 3-6 months, a probability to be employed comes to 50%, and what is more important, if overall duration of participation in measures comes to 6-12 months, a probability of job placement decreases to almost 37%. With time, a probability of job placement decreases significantly (Terävä et al., 2011; Pitkäaikaistyöttömien työllistyminen, 2011; Aho, 2008).

Labor market training remains one of the most important indicators of the integrative capacity of the labor market. The overall tendencies show that after completion of labor market training, more than half of unemployed persons remain in the same status of unemployment, whereas only a fourth finds a job in the general labor market. The probability of staying in the previous status of unemployment in a case of interrupted training is even higher, while a probability to be employed in the labor market is comparatively lower. Analyzing further tendencies and transitions between statuses after completion of labor market training, it becomes apparent that further training more often turns out to be a logical continuation of the adaptation process in the labor market. According to estimations, 34% of the overall number of unemployed people participating in labor market training start a course of employment, whereas 17.5% of unemployed people move to subsidized employment measure and only 15% of unemployed persons find a job independently (Tuomala, 2002, p. 18). In the overall context of labor market training, the preparatory training forms only a small part of it. Its primary aim is not necessarily direct job placement but improvement of opportunities for job placement. Therefore, preparatory labor market training implies partly further participation in vocational retraining. Consequently, an influence of preparatory labor market training upon the open labor market is lower than analogous influence of vocational retraining (Asplund, 2009, p.17).

Labor market segmentation and immigration

The labor market segmentation theory explains the mechanism, which cases the initial, predetermined market division into segments, groups, and classes; specified labor market segmentation entails creating occupational labor markets for immigrants. Importance of social position in segmentation is obvious, because an immigrants’ status in society and place in the social stratification depend on whether an immigrant has a job or not, what their income or employment status is, and what employment rate they has. An individual position in the social stratification has crucial importance in the public domain and the economic system. Education has crucial importance as well because it predetermines the income rate, chances, and individual opportunities in the labor market. Therefore, educational level has an influence upon individual opportunities in other public activity spheres.

As confirmed, the human capital predictors (i.e., education, occupation, work experience, and official languages proficiency) become statistically significant and strong predictors of earnings for immigrants (Buzdugan & Halli, 2009; Constant & Massey, 2005). Education turns out to be one of the major grounds for segmentation of immigrants in the labor market (Güell & Petrongolo, 2007; Gesthuizen & Wolbers, 2010; Wolbers, 2000). The devaluation of foreign education and credentials and the demand of work experience are viewed by institutional administrators as major barriers to labor market integration among immigrants. Due to this circumstance, immigrants suffer from occupational downgrading, are forced to switch careers, and experience loss of social status. Such a situation is often conditioned by specificity of immigration policies and labor market regulations, which give rise to pre-entry discrimination as concerning educational qualifications and places of education of immigrants (see Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006; Mata & Pendakur, 1999, Krahn et al., 2000, Bauder, 2003, Anisef, Sweet & Frempong, 2003, Buzdugan & Halli, 2009; Kogan, 2007, Kogan, 2004a, Kogan, 2004b).

life in a receiving society. As it is argued, one of the negative effects of segregation is blockage of integration and social mobility in a new society.

As previous researches show, the process of integration of immigrants at the labor market of various countries has similar tendencies; however, it often becomes complicated by factors of individual character as gender, age, educational level, family status, and children, or specificity of a country of origin of immigrants. In particular, the age has a significant influence upon the process of integration at the labor market, because frequency of transitions between statuses decreases proportionally age of immigrants; the duration of unemployment benefits is exclusively age-determined (Blau & Riphahn, 1999; Addison & Portugal, 2008; Caliendo, Tatsiramos & Uhlendorff, 2012; Bover, Arellano & Bentolila, 2002). On the other hand, transitions out of spells of unemployment and the continuity of unemployment are strongly gender-determined (Alba-Ramírez, Arranz & Muñoz-Bullón, 2007; Böheim & Taylor, 2002; Güell & Petrongolo, 2007; Stier & Levanon, 2003). The effects of unemployment benefit sanctions on re-employment probabilities are gender-determined (Müller & Steiner, 2008; Tatsiramos, 2009).

According to Blume et al. (2009), in developed countries immigrants experience risks of marginalization and unemployment more often than the native population. Uhlendorff & Zimmermann (2014) conclude that immigrants remain unemployed for longer than natives do, but the probability of leaving unemployment differs strongly with ethnicity. In comparison to the native population, immigrants realize more transitions “unemployment-employment-unemployment.” Immigrants less probably remain in the status “employment” than the native population, and move to a status “social protection” or “unemployment.” In comparison to the native population, immigrants have more difficulties to move into the status “employment” and this process takes longer time (Hansen & Lofstrom, 2009; Bevelander, 2001). For many immigrants self-employment becomes a way to avoid marginalization in a society. However, after self-employment or hired employment, unemployment remains a relatively dominating status at the labor market (Pollock, Antcliff & Ralphs, 2002).

Multiple researches on labor market segmentation of immigrants verify that this phenomenon develops owing to different origins. The dynamics of the sub-stratification of lower classes in the labor force is at the same time the cause for the further inflow of foreign workers and the explanation of increasing “flexibility” in terms of working conditions for immigrants. For example, in Sweden, a country with a long tradition of homogeneity built on a common culture, the integration policy for a long time aimed to preserve ethnic identity and attain equality with the Swedish-born population in order to provide immigrants with equal participation in different kinds of labor relations (Murdie & Borgegard, 1998).

In many aspects, the specificity of labor market segmentation is conditioned by the history of immigration to a country. For example, in multinational countries with a long history of immigration, migrant labor is increasingly differentiated parallel to the existence of significant mechanisms of duality in the labor market. On the one hand, the labor market consists of highly skilled migrants, who represent a growing section of global mobility and the most mobile demographic (so called “intellectual migrants”). On the other hand, it includes migrants who are directed into the secondary labor market, the one increasingly associated with “irregular” and humanitarian immigrants, in spite of the fact that many in the latter two categories possess higher education. This practice operates in the recruitment of some immigrants to “good” jobs, as well as some to “bad” ones, or to “good” sectors, as well as to “bad” sectors (Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006; Hiebert, 1999; Krahn et al., 2000; Portes & Stepick, 1985, Pedace, 2006, Rodriguez, 2004; Hudson, 2007; Constant & Massey, 2005; Reyneri, 2004; Fan, 2002; Behtoui, 2004; Schrover, van der Leun & Quispel, 2007).

Data and methods

Data

the careers of immigrants over time. The URA database contains information about the employment-seeking population as codes of employment (employment, unemployment, economic inactivity, etc.) and the changes in these codes in terms of the beginning and ending of unemployment, as well as apprenticeship periods. The URA database is all-encompassing, containing information about all unemployed people who have been registered with employment services in Finland. Only immigrants who have been registered in the URA-database as part of the “unemployed population” and, consequently, obtained a right to participate in programmes of adaptation for unemployed persons initiated by the government of Finland have been chosen for the present study.

Given the nature of the underlying data, we use methods applicable to discrete duration data. We estimate the time dependence of each transition simultaneously, allowing each transition to have individual time patterns and to be differently affected by the covariates. Our sample consists of unemployment durations and unemployment spells that terminate due to employment or other reasons. Thus, individuals are only followed from January 1952 up to December 2014, and ongoing spells at that latter date are interval-censored. This means that we know when a first unemployment period has been recorded and when a last unemployment period has ended in the URA-database. This enables us to treat these data as (discrete-time) duration data. We also wish to highlight that the first period (1952-1971) accounts for only 2.54% of observations (380 unemployment spells), the second period (1972-1991) accounts for 16.91% (2,534 unemployment spells), and the majority of observations belongs to the third period (1992-2014, 80.55%, or 12,072 unemployment spells).

Statistical model

In the case of the present research, transitions out of spells of unemployment are verified by means of discrete-time survival models, which are specified in terms of the discrete-time hazard and defined as the conditional probability that the event occurs in time t, given that it has not occurred before. In general, each person should be represented by a row of data for each month the person was at risk. We therefore expand the data and create a new variable, ‘month’, which denotes the months per person. We use notation T for the time in months taken to exit from a spell of unemployment, which can take integer values t = 1, 2,…, k. If the variable ‘event’ equals 1, we know that T equals ‘months’, and if ‘event’ equals 0, we know that T is greater than ‘months’. Discrete-time survival models are specified in terms of the discrete-time hazard, defined as the conditional probability that the event occurs at time t, given that it has not yet occurred (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2012, p. 750):

𝒉𝒕≡ 𝐏𝐫(𝑻 = 𝒕|𝑻 > 𝒕 − 𝟏) = 𝐏𝐫(𝑻 = 𝒕|𝑻 ≥ 𝒕) (1)

The discrete-time survival function is the probability of not experiencing the event by time t:

𝑺𝒕≡ 𝐏𝐫(𝑻 > 𝒕) (2)

We can derive the relation:

𝑺𝒕= ∏(𝟏 − 𝒉𝒔

𝒕

𝒔=𝟏

) (3)

We obtain estimated hazards as predicted probabilities by using a logistic regression model, where the covariates are dummy variables for each month:

𝒍𝒐𝒈𝒊𝒕{𝐏𝐫(𝒚𝒔𝒊= 𝟏|d𝒔𝒊)} = 𝒂𝟏+ 𝒂𝟐𝒅𝟐𝒔𝒊+ ⋯ + 𝒂𝒌𝒅𝒌𝒔𝒊, (4)

where ysi is an indicator for the event occurring at time s for person i and dsi = (d2si,…, dksi)’

is a vector of the corresponding dummy varia bles for months 2, …, k.

The likelihood calculated by binary regression models based on expanded data is simply the required likelihood for discrete-time survival data, and the resulting predicted hazards are their maximum likelihood estimates. To see this, we consider the required likelihood contribution for a person who was censored at time t, which is simply the corresponding probability𝑆𝑡𝑖 ≡ Pr(𝑇𝑖> 𝑡)(Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2012, p. 751). This probability is given by

𝑺𝒕𝒊= ∏𝒕𝒔=𝟏(𝟏 − ℎ𝒔𝒊), (5)

where hsi is the discrete-time hazard at time s for person i. In the expanded database, someone

corresponding likelihood contributions from binary regressions are the model-implied probabilities of the observed responses, Pr(ysi = 0) = (1 – hs), and these are simply multiplied

together because the observations are taken as independent, giving the required likelihood contribution for discrete-time survival. For an unemployed person who completed a period of unemployment at time t, the likelihood contribution should be:

𝐏𝐫(𝑻𝒊= 𝒕|𝑻𝒊> 𝒕 − 𝟏) 𝐏𝐫(𝑻𝒊> 𝒕 − 𝟏) = 𝒉𝒕𝒊∏(𝟏 − 𝒉𝒔𝒊

𝒕−𝟏

𝒔=𝟏

) (6)

Such a person is represented by a row of data s = 1, 2, …, t with y=0 for s ≤ t – 1 and y= 1 for s = t. The likelihood for binary regression is therefore Pr(y1i = 0) * … * Pr(yt-1,i = 0) * Pr(yti = 1),

as required.

We can then interpret the logistic regression model as a linear model for the logit of the discrete-time hazard:

𝒍𝒐𝒈𝒊𝒕{𝐏𝐫(𝑦𝒔𝒊= 1|𝐝𝒔𝒊)} = 𝑎𝟏+ 𝑎𝟐𝑑𝟐𝒔𝒊+ ⋯ + 𝑎𝒌𝑑𝒌𝒔𝒊

= 𝒍𝒐𝒈𝒊𝒕{𝐏𝐫(𝑻𝒊= 𝒔|𝑻𝒊≥ 𝒔, 𝒅𝒔𝒊)} (7)

Although we investigate how the marginal hazard evolves over time, the main purpose of survival analysis is usually to estimate the effects of covariates on the hazard. To allow for the important regressors, we expand the model

𝒍𝒐𝒈𝒊𝒕{𝐏𝐫(𝒚𝒔𝒊= 𝟏|d𝒔𝒊, 𝒙𝒊)}

= 𝒂𝟏+ 𝒂𝟐𝒅𝟐𝒔𝒊+ ⋯ + 𝒂𝒌𝒅𝒌𝒔𝒊+ 𝜷𝟏𝒙𝟏𝒊+ 𝜷𝟐𝒙𝟐𝒊+ 𝜷𝟑𝒙𝟑𝒊+ 𝜷𝟒𝒙𝟒𝒊 (8)

where xi = (x1i, x2i, x3i, x4i)’ is the vector of gender, education, birth cohort, and entrance

cohort. The first part of the linear predictor, a1, determines the so-called baseline hazard – the

hazard when xi and dis are zero vectors. The model could be described as semiparametric because

no assumptions are made regarding the functional form for the baseline hazard, whereas the effects of covariates are assumed to be linear and additive on the logit scale. The response variable y should be 1 if failure occurred (the period of unemployment ended) for the person that month, and 0 if the event is still censored (i.e., the period of unemployment has not been ended). A constant difference in the log odds corresponds to a constant ratio of the odds. For this reason, the model is often called a proportional odds model, not ordinal logistic regression. The model is also referred to as a continuation-ratio logit model or sequential logit model (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2012, p. 760).

In this model, the difference in log odds between individuals with different covariates is constant over time. We obtain the estimated odds ratios associated with the four covariates by exponentiation of the coefficients. We obtain the estimated hazards ĥsi from the log odds. To

obtain the cumulative products 𝑆𝑡= ∏𝑡𝑠=1(1 − ℎ𝑠) for each person, we use the relationship:

Ŝ𝒕𝒊= ∏(𝟏 − ĥ𝒔𝒊

𝒕

𝒔=𝟏

) = 𝒆𝒙𝒑 {∑ 𝐥𝐧(𝟏 − ĥ𝒔𝒊)

𝒕

𝒔=𝟏

} (9)

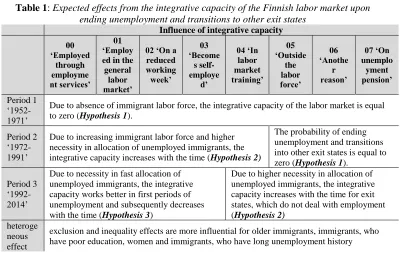

Based on above-described model, we expect to verify following predictions:

1) Our first prediction implies that the hazard does not change with time. Therefore, the probability of ending unemployment and transitions into other exit states is equal to zero (Hypothesis 1).

2) Our second prediction implies that the hazard increases with time. Therefore, the probability of ending unemployment and transitions into other exit states exceeds 1 (p>1) (Hypothesis 2).

3) Our third prediction implies that the hazard decreases with time. Therefore, the probability of ending unemployment and transitions into other exit states underestimates 1 (p<1) (Hypothesis 3).

Table 1: Expected effects from the integrative capacity of the Finnish labor market upon ending unemployment and transitions to other exit states

Influence of integrative capacity

00 ‘Employed through employme nt services’ 01 ‘Employ ed in the

general labor market’

02 ‘On a reduced working week’ 03 ‘Become s self-employe d’ 04 ‘In labor market training’ 05 ‘Outside the labor force’ 06 ‘Anothe r reason’ 07 ‘On unemplo yment pension’ Period 1 ‘1952-1971’

Due to absence of immigrant labor force, the integrative capacity of the labor market is equal to zero (Hypothesis 1).

Period 2 ‘1972-1991’

Due to increasing immigrant labor force and higher necessity in allocation of unemployed immigrants, the integrative capacity increases with the time (Hypothesis 2)

The probability of ending unemployment and transitions into other exit states is equal to zero (Hypothesis 1).

Period 3 ‘1992-2014’

Due to necessity in fast allocation of unemployed immigrants, the integrative capacity works better in first periods of unemployment and subsequently decreases with the time (Hypothesis 3)

Due to higher necessity in allocation of unemployed immigrants, the integrative capacity increases with the time for exit states, which do not deal with employment

(Hypothesis 2)

heteroge neous effect

exclusion and inequality effects are more influential for older immigrants, immigrants, who have poor education, women and immigrants, who have long unemployment history

Results

General description

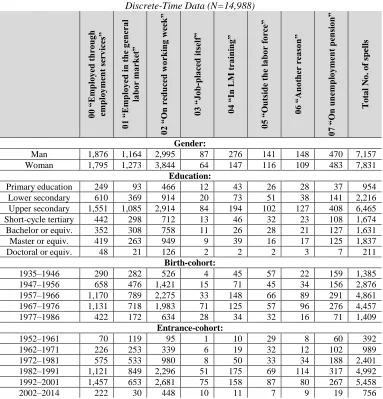

We move to specify time determinants and individual (socio-demographic) determinants of transitions out of unemployment. Hence, we analyse the time spent in unemployment and distinguish between eight subsequent destination states, characterized as employment, labor market training and non-participation. According to estimations in Table 2, a considerable share – approximately 45% – of the unemployment spells ended in job-placement on a reduced working week. Two other exit states are also found to be considerable: approximately 24% of unemployment spells ended in job-placement through employment services, while 16% of unemployment spells ended in job-placement in the general labor market.

Table 2:The distribution of state of exit of unemployment spells and their durations (N=14,988) Dura tio n (m o n th s) 00 “ Em p lo ye d th ro u g h e m p lo y m en t se rv ice s” 01 “ Em p lo ye d in th e ge n er al la b or m ar k et” 02 “ O n r ed u ce d wo rk in g we ek ” 03 “ Jo b -p la ce d itse lf” 04 “ In LM tr ain in g” 05 “ O u tsid e th e la bo r fo rc e” 06 “ Ano th er r ea so n ” 07 “ O n u n em p lo y m en t p en sio n” To ta l N o . o f spells

<1 372 64 997 28 5 21 5 42 1,534

1-3 1,469 321 2,867 99 57 57 30 156 5,056

4-6 722 282 1,569 10 59 20 38 112 2,812

7-12 475 373 950 4 68 32 30 142 2,074

13–24 224 422 272 1 87 41 48 137 1,232

> 25 409 975 184 9 147 86 106 364 2,280

Total No.

of spells 3,671 2,437 6,839 151 423 257 257 953 14,988

See explanation of exit states of unemployment spells at:

In general, more than 87% of unemployment spells are completed by reason of job-placement in one of these three forms (exit states 00-03). Table 3 also provides information on random samples of 7,157 spells for males and 7,831 spells for females. A majority of immigrants have upper secondary education (39.9%). The same tendency is clear when analysing completing unemployment spells that end in one of the studied exit states: a majority of job-placed immigrants have upper secondary education.

Table 3: Descriptive statistics on ‘exit states’ and main explanatory variables as applied to

Discrete-Time Data (N=14,988)

00 “ Em p lo ye d th ro u gh em p lo ym en t se rv ice s” 01 “ Em p lo ye d in th e ge n er al la b or m ar k et ” 02 “ O n r ed u ce d wo rk in g we ek ” 03 “ Jo b -p la ce d itse lf” 04 “ In LM tr ain in g” 05 “ O u tsid e th e la bo r fo rc e” 06 “ Ano th er r ea so n ” 07 “ O n u n em p lo ym en t p en si on ” To ta l N o . o f spells Gender:

Man 1,876 1,164 2,995 87 276 141 148 470 7,157

Woman 1,795 1,273 3,844 64 147 116 109 483 7,831

Education:

Primary education 249 93 466 12 43 26 28 37 954

Lower secondary 610 369 914 20 73 51 38 141 2,216

Upper secondary 1,551 1,085 2,914 84 194 102 127 408 6,465 Short-cycle tertiary 442 298 712 13 46 32 23 108 1,674

Bachelor or equiv. 352 308 758 11 26 28 21 127 1,631

Master or equiv. 419 263 949 9 39 16 17 125 1,837

Doctoral or equiv. 48 21 126 2 2 2 3 7 211

Birth-cohort:

1935–1946 290 282 526 4 45 57 22 159 1,385

1947–1956 658 476 1,421 15 71 45 34 156 2,876

1957–1966 1,170 789 2,275 33 148 66 89 291 4,861

1967–1976 1,131 718 1,983 71 125 57 96 276 4,457

1977–1986 422 172 634 28 34 32 16 71 1,409

Entrance-cohort:

1952–1961 70 119 95 1 10 29 8 60 392

1962–1971 226 253 339 6 19 32 12 102 989

1972–1981 575 533 980 8 50 33 34 188 2,401

1982–1991 1,121 849 2,296 51 175 69 114 317 4,992

1992–2001 1,457 653 2,681 75 158 87 80 267 5,458

2002–2014 222 30 448 10 11 7 9 19 756

Time is a significant factor in the cyclical nature of transitions to employment

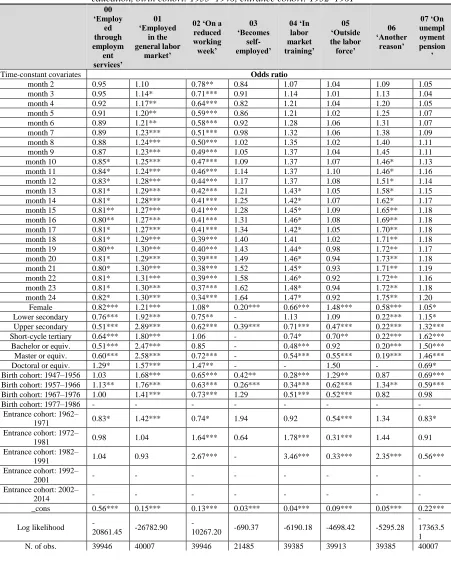

We specify a logistic regression for the expanded data with four covariates added to the dummy variables for months 2–24. We analyse here regularities of transitions out of unemployment spells of immigrants who remained unemployed during the 24 months and we look at probabilities of an end to unemployment during this period.

By expanding the data appropriately and defining a binary variable (failure or censoring for one of the eight exit states), we can obtain the estimated hazards as the proportions of failures observed each month. The data expansion allows for the conducting of the most common type of discrete-time survival analysis. The results of our estimates are reported in Tables 1, 2, and 3 in the Appendix for each of the three periods. These estimates refer to the sample periods ‘1952– 1971’, ‘1972–1991’, and ‘1992–2014’, yet only the first 24 months of the observation period are taken into account as the basic period during which the intensity of transitions is highest. In this case, we estimated the maximum likelihood of failure or censoring for one of the eight exit states and propose three models as separate regression models.

We now turn to time-constant covariates for each of the three models. We considered each of the 24 months as separate dummy variables and included them in the model, omitting the dummy variable for month 1. Regarding the coefficients of the dummy variables, their exponentials represent the odds ratio of completing spells of unemployment in a given month (given that an unemployment spell has not yet ended) compared to month 1, when xsi = 0. This model assumes

that the difference in log odds between individuals with different covariates is constant over time. As can be seen from Tables 1, 2 and 3 in the Appendix, the odds ratios of each of the 24 studied months are rather different in each of three models. So, for the 2nd period ‘1972-1991’

(Table 2 in the Appendix), the odds of ending an unemployment spell and transitions to employment through employment services are 0.85 times as great in month 10 (0.82 times in month 24) as they are in month 1 when all covariates take the value zero. Comparatively, for the 3rd period ‘1992-2014’ (Table 3 in the Appendix), the odds of becoming employed through

employment services are 0.84 times as great in month 4 (0.49 times in month 24) as they are in month 1. We therefore conclude that with every later month, the probability of transitions to employment through employment services decreases essentially for unemployed immigrants from the period ‘1992–2014’.

In estimating the general tendencies of the job placement of immigrants and comparing employment in the general labor market during the 2nd period ‘1972-1991’, the odds of transitions

to employment are already 1.14 times as great in month 2 (1.30 times in month 24) as they are in month 1 when all covariates take the value zero. Comparatively, for the third period ‘1992-2014’, the odds of transitions to employment are already 1.24 times as great in month 2 (5.08 times in month 24) as they are in month 1. Therefore, with every later month, the probability of transitions to employment in the general labor market essentially increases for unemployed immigrants from the period ‘1992–2014’.

Allocation on part-time employment, or employment on a reduced working week, also has its own specific features for immigrants from different periods. For example, for the 2nd period

‘1972-1991’, the odds of transitions to employment on a reduced working week are already 0.78 times as great in month 2 (0.34 times in month 24) as they are in month 1 when all covariates take the value zero. Comparatively, for the third period ‘1992-2014’, the odds of transitions to employment on a reduced working week are already 0.86 times as great in month 2 (0.14 times in month 24) as they are in month 1. Therefore, for immigrants from the periods ‘1992–2014’, the probability of employment on a reduced working week essentially decreases starting from the second month of unemployment.

The effect of gender, education, age and period effect in the cyclical nature of transitions to employment

Firstly, we find that for the first period ‘1952-1971’, the odds of transitions to employment through employment services for women is 0.70 times as great as they are for men. Therefore, women have less chance to be employed though employment services than men have. On the other hand, we find that for the second period ‘1972-1991’, the odds of transitions to employment through employment services for women are 0.82 times as great as they are for men. However, women realise more transitions to employment in the general labor market than men do (the odds are 1.21) and to employment on reduced working week (the odds are 1.08). Finally, for the third period ‘1992-2014’, the odds of transitions to employment though employment services and to employment in the general labor market are lower for women than they are for men. On the contrary, the odds of transitions to reduced working week and self-employment are higher for women than they are for men.

Secondly, education turns out to be a factor of the specific labor market integration of unemployed immigrants, because in many cases immigrants without any professional education still have a greater probability of gaining employment through employment services during the periods ‘1952–1971’ and ‘1972–1991’. We find that for the first period ‘1952-1971’ and the second period ‘1972-1991’, the odds of transitions to employment through employment services are higher for immigrants with primary education. On the contrary, the odds of transitions to employment in the general labor market are higher for immigrants with lower and upper secondary education for both the first and the second periods. For the third period ‘1992-2014’, we find important influence of educational background upon transitions into reduced working week for immigrants with bachelor degree, master degree or doctoral degree. The factor of professional education, however, significantly increases in importance for immigrants from the periods ‘1972–1991’ and ‘1992–2014’.

Thirdly, when estimating the influence of birth cohort upon transitions to employment, we find that for the second period ‘1972-1991’, the odds of transitions to employment in the general labor market are increasing for younger immigrants (from more recent birth cohorts). On the other hand, allocation on part-time employment is more probable for older immigrants. For the third period ‘1992-2014’, we find another tendency, when the odds of transitions to employment through employment services, employment in the general labor market are higher for younger immigrants than they are for older immigrants. Finally, the odds of transitions to reduced working week are lower for younger immigrants than they are for older immigrants.

To conclude, the period effect considered by means of the ‘entrance cohort’, affects the odds of transitions to reduced working week for immigrants from the second period ‘1972-1991’. Therefore, immigrants, who became unemployed later, have more chances to be employed on reduced working week than immigrants with longer unemployment history have. On the other hand, for the third period ‘1992-2014’, the odds of transitions to employment through employment services and to employment on reduced working week are higher for immigrants with shorter unemployment history, while employment in the general labor market is more probable for immigrants with longer unemployment history. Therefore, as might be expected, belonging to a later entrance cohort are associated with a greater probability of ending spells of unemployment (given that an unemployment spell has not yet ended) into employment through employment services and reduced working week.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of our analysis was to estimate influence of the integrative capacity of the Finnish labor market upon immigrant integration in the long-term perspective. In this paper, we studied what the time determinants of transitions out of unemployment spells into other exit states are, how micro-level determinants of unemployment affect the outcome of transitions out of unemployment spells and how a period, when unemployment occurs, affects general dynamics of transitions out of unemployment spells.

marginalization, pre-entry discrimination, and stigmatization. This research aimed to define how the patterns of labor market segmentation affect and predict continuity of unemployment and ‘outcomes’ of immigrants’ labor market integration. The overall results of the research argue that around 87% of immigrants realize transitions from unemployment to one of the forms of employment (e.g. employment through employment services, employment in the general labor market or job-placement with a reduced working week).

During the course of the research, we came to conclusion, which can be explained in relation to existing similar research on discrete-time hazard models. Like Alba-Ramírez, Arranz & Muñoz-Bullón (2007), we found that the unemployment duration dependence differs according to the route of exiting unemployment. According to our study, the largest share of unemployed people finds a job in the general labor market or on a reduced working week. We confirmed Hypothesis 1 as regard transitions out of unemployment spells during period ‘1952-1971’. We also confirmed Hypothesis 2 as regard transitions out of unemployment spells for immigrants during period ‘1972-1991’. We found that the tendency of employment in the general labor market and labor market training has increasing character. On the other hand, we found that employment through employment services and employment on reduced working week has decreasing tendency. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 as regard these two exit states has not been confirmed. Finally, we found that transitions to economic inactivity (‘outside the labor force’ and ‘unemployment pension’) remain unchangeable during first 24 months in unemployment. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 has been confirmed. In addition, we did not confirm Hypothesis 1 as regard transitions out of unemployment spells according to another (unknown) reason. We find that this tendency has increasing character.

We have shown that the probability of job placement through employment services is the highest for immigrants from the period ‘1992–2014’ and especially for these immigrants, this kind of job placement occurs with the highest probability already during first 24 months in unemployment, but has a decreasing tendency (Hypothesis 3 is confirmed). Comparatively, employment on a reduced working week essentially differs depending on the period when it occurs. The overwhelming majority of immigrants from the period ‘1992–2014’ are employed on a reduced working week, which occurs already during first several months of unemployment, but also has decreasing character (Hypothesis 3 is confirmed). We also confirmed Hypothesis 2 as regard immigrants from this period and find that transitions out of unemployment spells to labor market training, economic inactivity, and unemployment pension has increasing tendency. On the other hand, contrary to our assumptions, employment in the general labor market has increasing tendency with the time (Hypothesis 3 has not been confirmed).

We found that when adjusted, gender, education, age and previous unemployment experience have an even smaller effect on the predicted probabilities of transitions to part-time employment. In accordance with Böheim & Taylor (2002), who reveal that part-time employment is a more common destination state from unemployment for women than for men, we also find that transitions to part-time employment are more peculiar to women than to men (periods ‘1972-1991’ and ‘1992-2014’). Based on the discrete-time event history models, Gesthuizen & Wolbers (2010) explain the observed trends in education-specific transition rates to re-entry into employment from unemployment or inactivity. Their results prove the tendency for the more highly educated – who no longer have access to the best positions – to try to find a job further down the job hierarchy, thereby replacing the lesser educated and pushing them towards ever lower-skilled jobs and, ultimately, non-employment (unemployment and inactivity). With regard to transitions from unemployment to economic inactivity, the probability of realizing such transitions is hypothetically higher for immigrants with a higher professional education.

individuals with an education that is more oriented towards the labor market (occupationally specific or vocational) have a lower probability of becoming unemployed than those with a more general education.

In general, our research contributes to the dynamic analysis of the labor market integration of a specific group of the work-capable population specifically labelled ‘immigrants’. By means of the large representative dataset, we attempted to estimate the integration of immigrants as a discrete one process. On the other hand, the timescales of activity of unemployed immigrants – based on a dynamic approach through the analysis of transitions from unemployment – allow for the estimation of the long-term careers of the unemployed from a lifelong perspective. The approach undertaken in this research has a dualistic ‘descriptive-dynamic’ character because integration is understood as a never-ending process that is conditioned by a time period of long-term involvement and a context of solitary action. As every scientific work encounters challenges, this research has not avoided the pre-existing challenges of such investigations. This precondition also determines the nature of the methodological background of the research in the usage of such methods as discrete time survival models.

Development of the Finnish labor market has been affected by external and internal factors. The appearance of immigrants in Finland in the middle of the 1940s stipulated the development of a new approach to regulation of immigration and integration policy, occurring during a time of global economic restructures and new policy formations of the “welfare state.” So far, the role of immigrants in the labor market in Finland remains one of the most disputable issues. Integration into the labor market is more often presented from the positions of the macro approach, formulated by national authorities in the form of immigration and integration policy and legislation. The influence from integration policy in Finland is often considered in the context of macro policy (OECD, Eurostat, Migrant Integration Policy Index).

The fact that Finland has a position that is more beneficial among the OECD countries on indicators of labor market development is accompanied by a more effective policy of immigrant integration in comparison to the average level in other OECD countries. Finland has achieved an especially high integration index as concerning policy directions “access to the labor market” and “targeted support.” However, concerning limitations of access to the labor market, they still exist as conditioned by the time of entrance to the labor market. Immediate access to employment and access to the public sector by virtue of the immigration legislation and the entry permit regime for immigrants is restricted. Secondly, there are limitations to access to the general support for immigrants as conditioned by different conditions to education and training and recognition of academic and professional qualifications acquired outside the EU. Thirdly, concerning “targeted support,” restrictions to providing additional measures to further the integration of third-country nationals into the labor market exist, whereas support to access to public employment services is even absent. Finally, there are also limitations of workers’ rights as concerning equal access to social security and active policy of providing information on rights to migrant workers.

The integrative capacity of the labor market obtains a special role as contributing to specificity of labor integration of immigrants. The mechanism of fragmentation of the immigrant labor force is accompanied by the situation of when the boundaries of each segment of the labor market are seen to be explicable in terms of the workings of economic forces. The costs of entry to each segment of the labor market may be rather different. The nature of these costs indicates that a significant amount of time is taken in overcoming or reducing the barriers against entrance to the market.

differentiation of immigrants in specific trajectories of labor market integration. Taken together, these factors turn out to be crucial for the life trajectories of immigrants.

References

1. Addison, J., & Portugal, P. (2008). How do different entitlements to unemployment benefits affect the transitions from unemployment into employment? Economics Letters,101(3), pp. 206-209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2008.08.020

2. Aho, S. (2008). Työttömyyden pitkän aikavälin dynamiikka ja työvoimapoliittisten toimenpiteiden kohdistaminen. Työpoliittinen Aikakauskirja, [Dynamics of long-term unemployment and labour market policy measures. Finnish Labour Review], 4, pp. 21–34.

3. Alatalo, J., & Torvi, K. (2009). Joustoturva Suomen työmarkkinoilla: indikaattorit ja niiden tulkinta. TEM-analyyseja, [Flexicurity at the Finnish labour market: indicators and their interpretation. Employment Bulletin], 14, pp. 1–103.

4. Alba-Ramírez, A, Arranz, J.M., & Muñoz-Bullón, F. (2007). Exits from unemployment: Recall or new job. Labor Economics, 14(5), pp. 788–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2006.09.004

5. Alho, R. (2013). Trade union responses to transnational labor mobility in the Finnish-Estonian context. Nordic journal of working life studies, 3(3), pp. 133–153. https://doi.org/10.19154/njwls.v3i3.3015

6. Anisef, P., Sweet, R., & Frempong, G. (2003). Labor market outcomes of immigrant and racial minority university graduates in Canada, Journal of International Migration and Integration, 4(4), pp. 499–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-003-1012-4

7. Asplund, R. (2009). Työvoimapolitiikan vaikuttavuus Suomen näkökulmasta katsottuna. Työpoliittinen aikakauskirja, [Efficiency of labour market policy measures from the Finnish point of view. Finnish Labour Review], 52(3), pp. 6–20.

8. Bauder, H. (2003) “Brain abuse,” or the devaluation of immigrant labor in Canada.

Antipode,35(4), pp. 699–717. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-8330.2003.00346.x

9. Behtoui, A. (2004). Unequal opportunities for young people with immigrant backgrounds in the Swedish labor market. Labor, 18(4), pp. 633–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1121-7081.2004.00281.x

10. Bevelander, P. (2001). Getting a foothold: male immigrant employment integration and structural change in Sweden: 1970–1995. Journal of International Migration and Integration,2(4), pp. 531–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-001-1011-2

11. Blau, D., & Riphahn, R. (1999). Labor force transitions of older married couples in Germany. Labour Economics, 6(2), pp. 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(99)00017-2

12. Blume, K., Ejrnæs, M., Skyt Nielsen, H., & Würtz, A. (2009). Labor market transitions of immigrants with emphasis on marginalization and self-employment. Journal of Population Economics,22(4), pp. 881–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-008-0191-x

13. Böheim, R., & Taylor, M. (2002). The search for success: do the unemployed find stable employment? Labour Economics, 9(6), pp. 717-735. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(02)00074-X

15. Buzdugan, R., & Halli, S. (2009). Labor market experiences of Canadian immigrants with focus on foreign education and experience. International Migration Review, 43(2), pp. 366–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00768.x.

16. Caliendo, M., Tatsiramos, K., & Uhlendorff, A. (2012). Benefit duration, unemployment duration and job match quality: a regression-discontinuity approach.

Journal of Applied Econometrics, 28(4), pp. 604–627.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.2293

17. Colic-Peisker, V., & Tilbury, F. (2006). Employment niches for recent refugees: segmented labor market in twenty-first century Australia. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(2), pp. 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fej016

18. Constant, A., & Massey, D. (2005). Labor market segmentation and the earnings of German guest workers. Population Research and Policy Review, 24(5), pp. 489–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-005-4675-z

19. Fan, C. (2002). The elite, the natives, and the outsiders: migration and labor market segmentation in Urban China. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 92(1), pp. 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.00282

20. Gesthuizen, M., & Wolbers, M. (2010). Employment transitions in the Netherlands, 1980–2004: Are low educated men subject to structural or cyclical crowding out?

Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 28(4), pp. 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2010.06.001

21. Güell, M., & Petrongolo, B. (2007). How binding are legal limits? Transitions from temporary to permanent work in Spain. Labor Economics, 14, pp. 153–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2005.09.001

22. Hämäläinen, K. (1997). Active labor market programmes and unemployment, Taloustieteen osasto, Jyväskylän yliopisto, Mimeo.

23. Hämäläinen, K., Tuomala, J., & Ylikännö, M. (2009). Työmarkkinatuen aktivoinnin vaikutukset. Työ ja yrittäjyys, [Efficiency of labour market assistance activation. Work and Entrepreneurship], 7, pp. 1–68.

24. Hansen, J., & Lofstrom, M. (2009). The dynamics of immigrant welfare and labor market behavior. Journal of Population Economics, 22(4), pp. 941–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-008-0195-6

25. Hiebert, D. (1999). Local geographies of labor market segmentation: Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver 1991. Economic Geography, 75(4), pp. 339–369.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.1999.tb00125.x

26. Holm, P., & Tuomala, J. (1998). Työllistyneiden työsuhteiden kesto ja työvoimapolitiikka. Valtion taloudellinen tutkimuskeskus. VATT-keskustelualoitteita, [Continuity of subsidized employment and labour market policy measures.

Government Institute for Economic Research], 163, pp. 1–43.

27. Hudson, K. (2007). The new labor market segmentation: Labor market dualism in the

new economy. Social Science Research, 36(1), pp. 286–312.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.11.005

28. Jolkkonen, A., & Kurvinen, A. (2012). Työvoiman kysynnän ja tarjonnan kohtaanto aluetasolla ja ESR-hanketoiminnan merkitys – esimerkkinä Pohjois-Karjala.

Työpoliittinen Aikakauskirja, [The supply and demand for labour in the Northern Karelia. Finnish Labour Review], 55(2), pp. 46–63.

29. Kogan, I. (2004a). Labor market careers of immigrants in Germany and the United Kingdom. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 5(4), pp. 417–447.

30. Kogan, I. (2004b). Last hired, first fired? The unemployment dynamics of male immigrants in Germany. European Sociological Review, 20(5), pp. 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jch037

33. Laukkanen, E. (2012). Mitä työttömyyden päättymisen syyt kertovat julkisen työvoimapalvelun pitkästä linjasta? Työpoliittinen Aikakauskirja, [What do unemployment spells’ ending talk about long-term perspective of public employment services improvement? Finnish Labour Review], 55(3), pp. 6–19.

34. Mata, F., & Pendakur, R. (1999). Immigration, labor force integration and the pursuit of self-employment. International Migration Review, 33(2), pp. 378–402. https://doi.org/10.2307/2547701

36. Murdie, R., & Borgegard, L. (1998). Immigration, spatial segregation and housing segmentation of immigrants in metropolitan Stockholm, 1960-95. Urban Studies, 35(10), pp. 1869–1888. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098984196

37. Niessen, J., Huddleston, T., & Citron, L. (2007). Migrant Integration Policy Index, Brussels: the British Council and Migration Policy Group.

38. Pedace, R. (2006). Immigration, labor market mobility, and the earnings of native-born workers: An occupational segmentation approach. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 65(2), pp. 313–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1536-7150.2006.00453.x

39. Pehkonen, A. (2006). Immigrants’ paths to employment in Finland. Finnish Yearbook of Population Research, 42, pp. 113–128.

40. Peltola, M. (2005). Työmarkkinasiirtymät Suomessa. Työllisyyden päättymisen jälkeinen työmarkkinasiirtymien dynamiikka vuosina 1995–1999. Valtion taloudellinen tutkimuskeskus, VATT-keskustelualoitteita, [Labour market transitions in Finland. Further dynamics of transitions out of unemployment into employment during 1995-1999. Government Institute for Economic Research], 360.

41. Pitkäaikaistyöttömien työllistyminen ja syrjäytymisen ehkäisy (2011). Valtiontalouden tarkastusviraston tarkastuskertomukset. Tuloksellisuustarkastuskertomus, [Job-placement of long-term unemployed and elimination of discrimination at the labour market. TheNational Audit Office's publications], 331/54/09, #229/2011.

42. Pollock, G., Antcliff, V., & Ralphs, R. (2002). Work orders: analysing employment histories using sequence data. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 5(2), pp. 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570110062432

43. Portes, A., & Stepick, A. (1985). Unwelcome immigrants: The labor market experiences of 1980 (Mariel) Cuban and Haitian. American Sociological Review, 50(4), pp. 493–514. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095435

44. Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2012). Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. Volume II: Categorical Responses, Counts, and Survival. Stata Press. 31. Kogan, I. (2007). A study of immigrants’ employment careers in West Germany using

the sequence analysis technique. Social Science Research, 36(2), pp. 491–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.03.004

32. Krahn, H., Derwing, T., Mulder, M., & Wilkinson, L. (2000). Educated and underemployed: Refugee integration into the Canadian labor market. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 1(1), pp. 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-000-1008-2

46. Reyneri, E. (2004). Immigrants in a segmented and often undeclared labor market. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 9(1), pp. 71–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571042000179191

47. Ristikari, T. (2012). Finnish trade unions and immigrant labor, PhD Thesis. Institute of Migration, Finland.

48. Rodriguez, N. (2004). Workers wanted: Employer recruitment of immigrant labor. Work and occupations, 31(4), pp. 453–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888404268870

49. Schrover, M., van der Leun, J., & Quispel, C. (2007). Niches, labor Market Segregation, ethnicity and gender. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,33(4), pp. 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830701265404

50. Sengenberger, W. (2011). Beyond the measurement of unemployment and underemployment. The case for extending and amending labor market statistics, International Labor Organization.

52. Tatsiramos, K. (2009). Unemployment insurance in Europe: unemployment duration and subsequent employment stability. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(6), pp. 1225–1260. https://doi.org/10.1162/jeea.2009.7.6.1225

53. Terävä, E., Virtanen, P., Uusikylä, P. & Köppä, L. (2011). Vaikeasti työllistyvien tilannetta ja palveluita selittävä tutkimus. Työ ja yrittäjyys, [Job-placement of “hard-to-employ” –unemployed and research of Employment Services’ efficiency. Work and Entrepreneurship], 23.

54. Tuomala, J. (1998). Pitkäaikaistyöttömyys ja työttömien riski syrjäytyä avoimilta työmarkkinoilta. Valtion taloudellinen tutkimuskeskus. VATT-tutkimuksia, [Long-term unemployment and risks to move out from the open labour market. Government Institute for Economic Research], 46.

55. Tuomala, J. (2002). Työvoimakoulutuksen vaikutus työttömien työllistymiseen. Valtion taloudellinen tutkimuskeskus. VATT-tutkimuksia, [Influence of labour market policy measures upon job-placement of unemployed. Government Institute for Economic Research], 85.

56. Työllistämistukien työllisyysvaikutukset (2005). Valtiontalouden Tarkastusviraston Tarkastuskertomus, [Efficiency of labour market policy support upon job-placement.

The National Audit Office's publications], 136/54/05(112).

57. Uhlendorff, A., & Zimmermann, K. (2014). Unemployment dynamics among migrants and natives. Economica, 81(322), pp. 348–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12077

58. Wolbers, M. (2000). The effects of level of education on mobility between employment and unemployment in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 16(2), pp. 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/16.2.185

51. Stier, H., & Levanon, V. (2003). Finding an adequate job: employment and income of recent immigrants to Israel. International Migration, 41(2), pp. 81–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00236