JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WORK

& SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Volume 05, Number 01 & 02, 2014

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL WORK

V

ISVA-B

HARATIJSWSD is a bi-annual refereed journal to publish original ideas that will promote issues pertinent to social justice, well being of individuals or groups or communities, and social policy as well as practice from development perspectives. It will encourage young researchers to contribute and well established academics to foster a pluralistic approach in the continuous efforts of social development.

Editor:

Asok Kumar Sarkar Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan

Editorial Advisors:

Surinder Jaswal Professor, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai B. T. Lawani Director, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune Sukladeb Kanango Retired Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Sonaldi Desai Professor, University of Maryland, USA

Editorial Board:

P. R. Balgopal Professor Emeritus, University of Illinois, USA Monohar Pawar Professor, Charles Stuart University, AU Niaz Ahmed Khan Professor, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh D. Rajasekhar Professor, ISEC (Centre of Excellence), Bangalore Rama V. Baru Professor, JNU, New Delhi

Swapan Garain Professor, TISS, Mumbai

Kumkum Bhattacharya Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan P. K. Ghosh Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Debotosh Sinha Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Paramita Roy Associate Professor, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan

© Copyright 2014 by Department of Social Work, Visva-Bharati

The material printed in this journal should not be reproduced without the written permission of the Editor. The statements and opinions contained within this publication are solely those of the contributors and not of the Editor or Department of Social Work, Visva-Bharati.

For more information about subscription or publication, please contact: Prof Asok Kumar Sarkar,

Department of Social Work, Visva-Bharati,

I am happy to bring out this volume combining two issues, i.e. June and December 2014 together. It has presented a number of studies to address a few specific concerns of social development such as credit system among the tribals, agrarian change in north eastern India, student voluntarism, entrepreneurial skill development among the female students, vulnerability in slum areas, and infertility among educated working women. Apart from these, the volume also incorporates two descriptive articles and one book review. A glimpse about the contribution of the authors is as follows :

The first two articles focus on tribal issues. The study of Mohanty and Behera look at the credit system prevailing in rural and tribal areas and explores the impact of credit system on small and marginal farmers in general and tribal farmers in particular. There are 106 tribal families purposively selected from the six sample panchayats under Borigumma block. Authors suggest that there is a need of collective intervention by the CSOs, business entrepreneur, financial institutions and the government to address verious issues related to credit system in tribal areas. Chawngthu and Kanagaraj in the second article seek to answer how far the switchover from shifting to settled cultivation has improved the living conditions of Mizo tribe. It addresses several research questions with the help of a field survey using a pre-tested structured household interview schedule in two Mizo villages of Mizoram.

Next two articles, though research based work, have used secondary sources of data. Varghese’s article, in order to get a comprehensive understanding of student voluntarism and its place in society, intends to make a study on the views of three important leaders and thinkers such as Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore and Swami Vivekananda who have contributed to Indian approach on subject of education and student volunteerism. Lahiri, Ghosh and Bhattacharjee have examined secondary documents such as government reports, articles and research papers to review upon the introduction of entrepreneurial development courses at secondary and higher secondary level to female students. The study followed qualitative research approach to investigate the scope of entrepreneurship education in the schools of West Bengal.

exploitation in the slums of Dhaka city. His survey of 150 children shows the existing socio-economic and cultural livelihood pattern of the slum dwellers along with the children. He recommends some altruistic measures may be considered in safeguarding children from further social menace and grievances. Mukherjee’s article states the experiences of a few cases of educated working women who suffered with infertility problems. Her contribution is a part of a doctoral research that was carried out in three clinics of Kolkata such as Surgey centre, Genome and AMRI clinic.

Last two articles are descriptive in nature and inclue the components how NGOs can contribute in social development. Biswas’s article proposes to deal with different aspects related to creation of widen scope of marketing opportunities of craft articles in ameliorating socio-economic condition of artisans and ultimately to see the improvement in quality of life of artisans. Banerjee shows in her article how neonatal death is a barrier of development. She provides an impression on community based interventions and community participation in successful reduction of neonatal death which supplements strategic action on promoting neonatal health and sustainable community development.

The volume ends with a book review critically written by Debarati Sarkar. As we are late to release this volume, the book written in 2015 has been incorporated in this issue of 2014. Hope readers will find the entire volume meaningful and as a good piece of reading for further thought.

Asok Kumar Sarkar Editor

______________________________________________________________ Editor’s Note

Credit System in Tribal Agricultural Practices :

A Case Study from Odisha 1

Goutam Kumar Mohanty & Minaketan Behera

Shifting Cultivation to Settled Agriculture :

Agrarian Change and Tribal Development in Mizoram 14 Lalengzama Chawngthu & Easwaran Kanagaraj

Student Voluntarism and Social Service in Colonial India – A Study on Three Thinkers :

Gandhi, Tagore and Vivekananda 44

Joseph Varghese

School Education and Entrepreneurial Skill Development : Empowering Women from Grassroots Level 60

Sudeshna Lahiri, Rupa Ghosh & Indrani Bhattacharjee

Vulnerability of Slum Children in Dhaka City :

How Do They Survive? 77

Md. Habibur Rahman

Infertility among Educated Woking Women : An Experience of Cases Reported in

Selected Clinics of Kolkata 90

Paramita Mukherjee

Promotion of Traditional Art and Craft Products Establishing Market Linkages – An Experience of

NGOs in Human Development 109

Manoj Kumar Biswas

Neonatal Death - A Road Block against

Community Development 123

Piyali Ghosh Banerjee

Book Review 132

Credit System in Tribal Agricultural

Practices : A Case Study from Odisha

Goutam Kumar Mohanty

#Minaketan Behera

* AbstractAgriculture and forest are the two main sources of livelihoods for tribal people. Credit is an important ingredient to enhance the productivity of the agriculture sector for the farmers, who are risk-taking entrepreneurs. A safe, easy and adequate credit facility, from both formal and informal sources is an important requirement for sustainable economic development of the tribal population. In India, at present a multi-agency approach comprising of co-operative banks, scheduled commercial banks and RRBs has been followed for providing credit to agricultural sector. Over time, spectacular progress has been achieved in terms of the scale and outreach of institutional framework for agricultural credit. But it was limited within the elite class people. Being the tribal poor, belongs to the small and marginal farmers category and some extend landless agricultural labourers, could not access the formal banking institutions for availing credit facilities. They still fall back upon indigenous and traditional sources of credit which leads to exploitation in several ways. The paper aims to look at the credit system prevailing in rural and tribal areas and their impact on small and marginal farmers in general and tribal farmers in particular.

Keywords: Tribal entrepreneur, accessibility of credit facilities, financial

institutions

Introduction

Agriculture is the primary source of employment for rural people in India. Agriculture accounts for about 16 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employs more than 2/3rd of the labour force. The importance of farm credit as a critical input to agriculture is reinforced by the unique role of Indian agriculture

———————————

# Additional Programme Officer, ST & SC Development Department, Government of Odisha. TDCCOL Building, 2nd Floor, Rupali Square, Bhoi Nagar, Bhubaneswar- 751022.

in the macroeconomic framework and its role in poverty alleviation. Rural farmers are lacking in capital for investment which compels them to knock the door of any financial source, either formal or informal (Samal, 1992). The formal institutions are generally very formal in nature and strictly follow their lending principles. Without documentation process and without securities the formal institutions will not sanction a single pie to the customers. The quantum of loan depends upon the value of assets that a farmer wants to keep as mortgage with the bank. As majority of them are small and poor farmers, they are generally unable to keep any mortgage. Farmers take lots of pain for collecting required papers from different departments to fulfil the pre-requisite criteria of documentation procedures to obtain loan from the banking institutions. But as per the banking principles and guidelines without fulfilling required criteria, nobody can avail loan. However, in some cases where farmers meet the requirements of the institutions, still they fail to access it in time because of the lengthy loan sanctioning process. Even if they get the loan the amount might be utilized for the other purpose than agriculture. Three major challenges before farmers to avail credit from the formal banking institutions for agriculture purposes such as the documentation process, quantum of loan and timely disbursement (Readdy, 2010). Due care is yet to be taken up. When the farmers failed to avail loan in time from the institutional sources they are compelled to knock at the door of informal sources of credit like moneylenders, traders, and sahukars etc. Informal financial institutions generally do not adhere to much formal process like documentations, records and not adhere to norms, principles, guideline set by RBI. The farmers generally avail loans from the informal sources like moneylenders, merchants, traders, shopkeepers, relatives, and friends etc. Face value plays a very important role in sanctioning informal loan. Interest rate also depends upon the person who is taking loan and it varies from source to source. But definitely it is much higher than the formal financial institutions.

Productive investment of loan in agriculture refers to land development works, purchasing modern machineries and equipments, seeds, fertilizers etc. These agricultural packages will help in higher return from the land. Formal financial institutions are interested in financing for this purpose because it is expected that they would get better repayment performance from the farmers

Unproductive purposes of using credit means it does not provide any return out of the investment e.g. expenditure on marriage, social gathering, festivals, constructing houses, purchasing gold etc. are treated as a utilization of credit for unproductive purposes. From economic point of view such expenses may be unproductive but from the individual and social point of view it may be essential to the person concerned. Being a social animal you need to go along with the society at any point of time. You cannot detach yourself from the society. But formal financial institutions usually do not extend their support for encouraging investment on unproductive purposes, because they look it from business point of view, and not from the point of view of social phenomena. But in case of money lenders, they lend money for any purpose, either productive or unproductive. Hence they are generally popular among the people mostly living in rural areas.

though banks have financed to agriculture sector but few influential families have dragged this programme in their favours i.e. major portion of loan consumed by the least percentage of people.

There were lots of factors responsible for inaccessible of the formal banking institutions by the farmers in general and tribal in particular. These were; clumsy & lengthy process, hectic documenting procedure, timely non-availability of loan, asked to come to the bank frequently, not sure of getting loan in a particular date, farmers were unable to give tangible assets as mortgage and finally policy decision which influence the system. Gradually, banks are now becoming tribal friendly. Therefore, tribal farmers are now approaching the institutional sources for credit.

The present study is being carried out as a case study in Borigumma block of Koraput district to know the state of tribal agriculture and also to know the types of agrarian inputs which are used by them along with the kind of facility they avail form the mainstream institutions, particularly, from the financial institutions. The study also aims at to know more about the practical difficulties faced by the tribal farmers while approaching the formal financial institution.

Objectives of the Study

The present study is carried out with the following objectives.

i) To understand the functioning of existing credit system in rural and tribal areas.

ii) To explore the access and utilizations of various credit facilities available in these areas by the rural tribal farmers. iii) To know about the difficulties faced by tribal farmers in availing institutional credits visa-vis the influence of non-formal credit sources in recent years.

iv) To study the extent of timely repayment of credit to the credit institutions by the tribal farmers.

Material and Methods

The present study has been carried out in Borigumma block of Koraput district for an in depth understanding of the prevailing credit system in tribal areas. Koraput district consists of 14 blocks. Borigumma is one among them. It consists of 50 percentage of ST and 15 percentage of SC population. Again 88 percentages of people come under BPL category (Government of Odisha, 2001a). Majority of the people depend upon agriculture. Agriculture is the main source of livelihood of the tribal living in the block. Simple random sampling method has been used for conducting the study. The block consists of 30 Gram Panchayats. Twenty percent of the panchayats in the block i.e. six panchayats fall under this study periphery. One village, from the each sample panchayats have been selected randomly by looking at the concentration of ST households. A sample size of 20 percent of tribal farmers has been taken purposively from each village for an in-depth study on the subject concerned. There are 106 tribal families selected from the six sample panchayats for the present study to know about the tribal agriculture and their credit pattern.

Demographic Details of Studied Villages

The Block under study is tribal dominated Block. About 50% of the Households come under ST category followed by 15.68% of SC households in the Block (Government of Odisha, 2001b). Around 60% of the household in 6 surveyed villages are tribal. Only ST households are taken into considerations for data collection. There are 796 households in the six sample villages out of which 479 households (60%) are tribal. Out of 479 tribal households 106 households (22.13%) are taken for an in depth study. From the demographic analysis of the six sample villages it is revealed that 60% of the households are tribal households and 25% are SC households. Hence, 85% of the households in these villages belong to STs and SCs combined. In the total population of the sample villages (418) males (231) outnumbered the females (187).

tribal. The basic infrastructure i.e. road and communication, electrification etc is lacking in the interior tribal villages.

The study revealed that out of the sample households surveyed, 3 families (3%) are landless, 36 families are marginal farmers (34%), 51 families are small farmers (48%), and only 16 farmers are large farmers (15%). It is also revealed that the 15% of big farmers' posses 49% of land, 48% of small farmers possess 44% of land and 34% of farmers have only 7% of land. This indicates that the land distribution pattern is very unequal among the tribal farmers in the study area. The study shows 97% of families have access to some amount of land and the average land holding is 2.84 acres which include dongara, shifting and paddy land. But the major portion of land (49%) is dragged by only 15% of farmers. The data analysis also reflects that 37% of families do not have paddy land or land which is meant for only paddy cultivation. It is found that 79% of families of the sample depend on agriculture and agriculture labour work.

Livelihood Pattern

The livelihood pattern indicates 79% (52% & 27%) of families depend on agriculture and agriculture labour work respectively, 11% of families have reported that collection of minor forest products and 8% families reported that livestock rearing were their main source of livelihood. This shows that agriculture is the main sources of livelihood for these tribal. On the one hand 82% of families come under small and marginal farmers' category and they possess only 51% of land and on the other side only 15% of large farmers possess 49% of land. The average land holding ranges from 0.04 acres to 5 acres. Thirdly, 37 percentages of families do not have paddy land.

In addition to cultivation of land the tribal farmers in the sample villages go for collection of fire woods, and other forest produces from the nearby forests. Out of the forest collection, they consume a part of it and the rest they sell in the market in order to earn some money.

major proportion of the livestock is utilised in ritual festivals and other socio-religious activities. The time has come to motivate the tribal families to adopt livestock rearing on a commercial basis. The crops grown in these areas are ragi, maize, paddy, vegetables, sugarcane and pulses etc. These crops are treated as staple food for the tribals except sugarcane and maize. In order to meet food security either equal distribution of land is necessary or landless families be provided with some land by the government to meet with their land hunger or the marginal landholders to make their holdings economically viable.

Financial Support to Farmers

Credit is the key input in increasing production in agriculture sector. These are supplied by formal banking institutions, SHG, MFI or informal money lender, sahukar and relatives. This block has good number of formal banking institutions i.e. 10 comprised of 1 SBI, 1 KCC, 2 LAMPS and 6 UGBs branches. The average coverage per bank branch is 3610 households. It may be mentioned here that 3 UGBs, 1 KCC, 1 LAMPS and 1 SBI are coming under our study areas. The average distance covered by a farmer is 8 kms. The 65 percent of credit comes from formal banking institutions; SHG/ MFI contributes 29 percent and 6 percent of credit from money lenders. This indicates that role of moneylenders in tribal areas has come down, and institutionalized financial institutions are taking their hold in these areas.

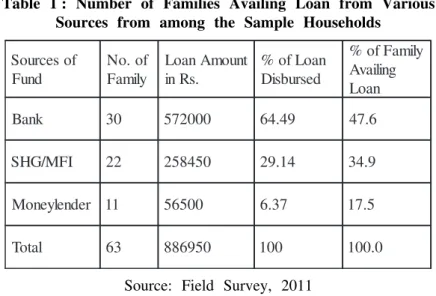

Out of 106 households' in the sample villages, only 63 families' availed loan from various sources. Among 63 families only 30 famers families (47.6%) are linked with formal banking institutions, 22 farmers (35%) have obtained loan from SHGs and 11 farmers families (17.4%) from money lenders. The paper also indicated that 65% of loan, are disbursed by formal banking institutions followed by 29% by SHG and 6% by moneylenders.

(81%) availed only 48 percentages of loan. The above 12 farmers were comparatively big farmers. This indicates that the big farmers have dragged more amount of the loan from the banks, because they have more lands with them which can be mortgaged to the banks to obtain loans. The table also indicates that 65 percentages of credit disbursed by the bank followed by 29 percent by SHG/ MFI which represent a good total of loan portfolio. Importantly these 65 percentages of loan financed by bank was only to 30 farmers which stand only 47.6 percentages of total farmers who availed loan from different banking sources. The 29 percent of loans are taken by only 22 farmers which stands 34.9%. This shows that people have better access to SHG/MFI and formal banking institution rather approaching traditional moneylenders. Combinedly it constitutes 82.5%. These 6 percent of loans are disbursed by money lenders stands at 17.5 percent only. In the past moneylenders, traders, sahukars were providing major amount of credit to the tribals. With the opening and functioning of banking institutions and cooperative societies in rural areas and with functioning of SHGs, the importance of indigenous moneylenders is gradually coming down. The details are given in the table below.

Table 1 : Number of Families Availing Loan from Various Sources from among the Sample Households

f o s e c r u o S d n u F f o . o N y l i m a F t n u o m A n a o L . s R n i n a o L f o % d e s r u b s i D y l i m a F f o % g n i l i a v A n a o L k n a

B 30 572000 64.49 47.6

I F M / G H

S 22 258450 29.14 34.9

r e d n e l y e n o

M 11 56500 6.37 17.5

l a t o

T 63 886950 100 100.0

Constraints in Getting Loans

There are difficulties and issues which arise in availing loans from banking institutions. These are; (a) the procedure takes long times, which compel farmers to leave hope in getting credit. (b) The lengthy process also insists farmers to approach informal sources for availing fund. The poor tribals leave their work; spend money from pocket to reach at the bank covering a long distance. But the farmers have very little hope for getting loan on the same day. (c) The documents and procedures that a banking institutions demand are difficult to meet on the part of a poor tribal farmer for which they need to contact middlemen who will assist them for collecting all required documents. It is found that about 60% of the loan holders experienced difficulties in getting loan from banks which includes collateral security deposit is a pre-condition for accessing loan, un-availability of loan in time, approaching banks several times, distance of banks from the place of living of respondents, working time of the Banks, non-provision of second time loan if first time loan is due, too many forms to be filled up etc. but they feel comfortable with regard to rate of interest charged by banks.

Credit Utilization Pattern

The table 2 give a glimpse of loan disbursed for various purposes. The loonies have availed loans and utilized for six purposes. The credit

Table 2 : Credit Utilization Pattern n a o L f o e s o p r u

P AmountinRs %ofLoanUsed

n o i t c u r t s n o C e s u o

H 29000 3.27

d e i l l A & e r u t l u c i r g

A 748450 84.38

s s e n i s u

B 6000 0.67

A G

I 78000 8.80

e g a i r r a

M 23500 2.65

l a v i t s e

F 2000 0.23

l a t o

T 886950 100.00

utilization pattern revealed that 84.38% of loans are used for agriculture and allied activities, followed by other Income Generating Activities (9.05%), house construction (3.27%) and social gathering (2.88%).

Bank wise Loan Portfolio

The major credit provider is the SBI followed by LAMPS and UGB. Major portion of loans were utilized for agricultural purposes. Out of 65 percent of loan disbursed by formal banking institutions to 30 (out of 63 farmers) farmers (47.6%). SBI gave loans to 13 farmers which amounts to 48% of total institutional credit, 17% by UGB to 9 farmers (30%), 4% by KCC to 2 farmers (4%) and 31% by LAMPS to 6 farmers (31%). After establishment of RRBs in rural areas people are availing financial benefit in terms of loan at their door steps. The data revealed that banking institutions are gradually providing better financial support to the tribal farmers. But these banking institutions with little more initiative can provide more proactively better financial assistance to all the farmers. Large farmers with more land have better financial access than small and marginal farmers having less land.

Repayment of Loans

As per the credit disbursement analysis, it is found that farmers are depending more on the formal sources. People have now realized that they have been exploited by the Moneylenders since years together who charged them very high interest which ranged from 60-120 percent per annum. Loan is repaid generally after the harvest is over. It is reported that all the 30 farmers who took loan from bank are regularly repaying the loan as per the repayment schedule of the bank. They believe that, if they are unable to repay the loan their property which is kept with bank as mortgage will be ceased by the bank. The tribal are honest borrowers. They have perception that even if they are not able to repay the loan, their successor will have to pay. Another notion is they (defaulter) are going to be deprived from second loan or subsequent loan by the bank. All these factors are responsible for good repayment of loan to the banks. It is found that repayment rate stands at above 80 percent.

SHGs mostly provide loans for cultivation at a small scale and also for petty business. It provides loan with less interest. It does not require collateral security from members for providing loan. Members' attendance, adhering group principles, regular savings and loan repayment performance along with interest to groups are considered as indicative parameters for sanctioning loan to members. SHGs conduct credit requirement process/ appraisal for its members to know the capacity of the borrower & its past records and purpose of loan being asked. The peer pressure acts as a mechanism for better repayment which stands above 90%. It is needless to mention that SHGs provide loan to its members for all necessary requirements whereas banking institutions give loan for specific productive purposes. Repayment performance of SHG to bank is comparatively better. It happens because loan repayment performance of members to SHG is also very goods. It works due to peer pressure from the members in a SHG and SHG federation. The loan repayment to moneylenders is also good because of fear of losing their mortgage items kept with the money lender. The repayment performance of the farmers to the banks also has improved which is above 80 percent. Out of 11 farmers who availed loan from moneylenders, 6 farmers said that they have repaid the loan by working with the sahukars in lieu of loan repayment. This amounts to the system of attached labour. Previously it was termed as goti. The repayment rate of bank loans shows a positive sign, whereas we found some problems in government sponsored schemes.

The present study also revealed that 94 percent of loan has been disbursed by formal banking institutions to 83.5% families out of the total number of families who have taken loan. This shows that the traditional money lending practices has come down and people are now aware of formal banking institutions. But still, efforts are needed to bring rest of the rural tribal farmers under the fold of institutionalized credit system.

Loans from Moneylenders

interest rate ranges from 60-120% per annum. They collect loan weekly, monthly or yearly basis depending upon the volume of loan taken. From the study it is found that people are paying instalments in monthly and half-yearly basis. But in most of the cases farmers repay the amount after harvesting the crops. They generally do not become defaulters to moneylenders, as they know that moneylenders can take very hard methods of collecting the loan. But in spite of that people are facing problem in clearing the loan amount because the high interest accumulated with the principal which is a real challenge for a poor tribal farmer.

Conclusion and Suggestions

Notes

1. The recommendations of the Committee included rebuilding of

cooperatives at all levels, cooperative marketing, multipurpose societies at larger level, commodity specific marketing societies, multipurpose PACSs at village level to undertake farm inputs and product marketing.

References

Government of Odisha, (2001a), District Statistical Handbook Koraput, Bhubaneswar : Directorate of Economics and Statistics.

Government of Odisha (2001b), Census of India, Bhubaneswar :

Directorate of Census Operation.

Samal, J. (1992), Some Aspects of Tribal Economy – A Case Study of Koraput District, Ph.D. Thesis.

Shifting Cultivation to Settled Agriculture :

Agrarian Change and Tribal Development in

Mizoram

Lalengzama Chawngthu*

Easwaran Kanagaraj#

AbstractShifting Cultivation has been one of the main livelihood options for many a tribe in India from time immemorial. It is widely practiced in the hill region of the North Eastern states. Although practiced widely it has been construed as one of the major challenges to tribal development in India over many decades. Hence, respective state governments have implemented a number of programmes to wean people away from the ecologically destructive practice of shifting cultivation. Yet one major question that remains unanswered is how far has the switchover from shifting to settled cultivation improved their living conditions? Another closely related question is regarding the nature of change in the tribal agrarian structure in the wake of the switch to settled cultivation. The present paper addresses these research questions with the help of field a survey using a pre-tested structured household interview schedule in two Mizo villages in Mizoram.

Keywords: Shifting Cultivation, Settled Agriculture, Jhum, Tribal Development,

Agrarian Transformation, Agrarian Change

Introduction

The present paper attempts to assess the impact of agrarian change from shifting cultivation to settled agriculture on the tribal living conditions in Mizoram. Shifting cultivation has been viewed as one of the challenges to tribal development in India over many decades (Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj, 2008). Shifting cultivation is an agricultural system characterised by rotation of field rather than of crops by short period of cropping alternating with long fallow periods and by means of slash and burn (Sachidananda, 1989). Its

———————————

* Dr. C. Lalengzama is Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Higher and Technical Institute, Mizoram (HATIM), Lunglei - 796 701. E-mail: teachongthu@gmail.com

other features are clearing by means of fire, absence of drought animals and manuring, use of human labour only, employment of dibbling stick or hoe, short periods of soil occupancy alternating with fallow periods.

Tribal communities and hill people have practiced shifting cultivation in India from time immemorial. It is widely practiced in the hilly regions of the North Eastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. About 10 million hectares of tribal land stretched across 16 states is estimated to be under shifting cultivation (Eswaraiah, 2003). According to a recent estimate of Forest Survey of India based on satellite images, 1.73 million hectares of land is affected by shifting cultivation in the Northeast India, while an estimated 12 per cent of tribal population in India still practices shifting cultivation, the number of families involved in shifting cultivation is estimated to be 4.5 lakhs (Darlong, 2004)

Shifting cultivation is accepted as an early stage of agricultural evolution which is still practiced in different parts of the world across different cultures (Rolwey-Conway, 1984). Shifting Cultivation is not only practiced in India but it is widely prevalent among the indigenous communities, particularly in Africa, Latin America and also parts of Asia.

conducted a number of studies on these aspects of social structure (Athreya et al, 1990; Harris, 1982; Mukerjee, 1949; Shah, 2013; Gadgil et al, 1983; Thorner, 1968) in various agro climatic zones of India. There are studies on the changes in the agrarian structure and its impact on rural development (Harris, 1982; GOI, 2007). There are studies which focus on the agrarian reforms (Joshi, 1969) and agricultural technology (Brass, 1990; Basant, 1987; Byres, 1981) and their impact on the agrarian structure as well as rural living conditions.

As agriculture is the main source of livelihood for most of the tribes, there are a number of studies on tribal agriculture in India. In this area, studies have concentrated on the agrarian structure and change, as well as crucial agrarian issues of shifting cultivation and land alienation (Saravanan, 2001; Karuppaiyan, 1990a). On shifting cultivation too there is copious literature in India as many tribes depend upon that for their sustenance. The studies generally focus on social and economic aspects shifting cultivation in different contexts such as jhum cycle, ecological consequences, cropping pattern, input use (Sachidananda, 1989), willingness to switchover to settled agriculture (Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj, 2008) etc.

There are also studies on the tribal development, especially the living conditions and the livelihood of the tribal households in different areas (Ramachandran, 2012; Rajarathnam and Guruswami, 1987; Karupaiyan, 1990b; Manivannan, 1989). Some have attempted to study inter-tribal variations in tribal development (Kanagaraj, 2014).

From the overview of literature it could be observed that there are a number of studies which have been conducted in varied agrarian and tribal contexts. Social scientists, especially the economists, sociologists, anthropologists, historians, etc., have explored the agrarian question from different disciplinary angles, varied theoretical perspectives and methodological orientations. Among the theoretical approaches, political economy is predominant while the quantitative approach is the methodological orientation that is prominent. In spite of these, a few research gaps could be observed.

confined itself to one village in the vicinity of Aizawl town. The findings of this study may not be reflecting the real situation in Mizoram.

Secondly, a few studies focus on impact of the switchover from shifting cultivation to settled agriculture on the agrarian structure (Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj, 2008; Ninan, 1992). Even these studies could not demonstrate clearly the effect of agrarian change on the tribal development as they did not operationalise the concept of tribal development.

Thirdly, social workers have not adequately researched on tribal development, i.e., tribal livelihood (Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj, 2008) or living conditions (Kanagaraj, 2005). The present study tries to fill these gap by comparison of living conditions of the shifting cultivators and settled agriculturalists.

This study is policy oriented and its findings would be useful for policy makers, planners, civil society organizations as well as social workers at multilevel who are concerned with tribal welfare in the North-East. The results will show the directions for designing appropriate policies for promoting sustainable agriculture in the North-East. It will also benefit civil society organisations to develop advocacy strategies. Social workers at the micro, mezzo and macro levels will be able design appropriate intervention strategies for promoting tribal development and empowerment.

The present paper is presented in five sections. The first section presents an over view of shifting cultivation in Mizoram. In the second section the research problem and methodology are presented. In the third section a brief description of the study village is presented. The results and discussion are presented in the fourth section. In the last section concluding observations and suggestions for policy makers is presented.

Shifting Cultivation in Mizoram: An Overview

Mizos have been agriculturists from the beginning of the 18th

The culture of the Mizos is intrinsically woven with their practice of shifting cultivation. The important festivals of Mizos, viz., Chapchar Kut, Pawl Kut and Mim Kut, are in fact associated with the various stages of shifting cultivation (Sen, 1992).

In Mizoram, the livelihood base of a majority of the population is cultivation, especially shifting cultivation. In the state, 61 per cent of the working population depends on agriculture and of which nearly 55 per cent were cultivators and 6 per cent were agricultural labourers according to the 2001 census. According to the statistical abstract of Department of Agriculture and Minor Irrigation, Government of Mizoram (2004), out of 738 villages and 1,54,643 households, 89,454 (57.85%) are cultivator households in Mizoram. Among the cultivators 78,195 (87%) households are practicing jhum and wet rice cultivation is practiced by 11,301 households (13%) (Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj, 2008).

A predominant majority of the households are depending on shifting cultivation for their livelihood over all the districts of Mizoram except Aizawl. Of the 1, 54,643 households in the state, more than one half depend on shifting cultivation (60%). More than three-fourth of the households of the districts of Champhai (77%), Kolasib (77%) and Saiha (75%) are shifting cultivators. Likewise, more than two-thirds of the households of Mamit (68%) and Serchip (68%) are practicing shifting cultivation and one half of them in the districts of Lawngtlai (62%) and Lunglei (58%) are jhumias. On the other hand, over one-third of the households of the Aizawl (34%) district depend on shifting cultivation (GOM, 2004).

As regards the agrarian structure of Mizoram, a predominant majority of the cultivators are marginal farmers cultivating less than one hectare of land. Seventy per cent of the cultivators are marginal farmers (less than 1 Hectare), 20 per cent of them are small farmers, while medium and large farmers constitute 6 and 4 per cent. The mean size of land holding was worked out to 1.6 hectares (Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj, 2008).

and large farmers control over 60 per cent of land (Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj, 2008).

Research Problem

The present study focuses on the impact of agrarian change, i.e., the switchover from shifting cultivation to settled agriculture on tribal development in Mizoram from a social policy and social work perspective. Agrarian structure is probed in terms of the nature of land ownership and distribution of land across size of land holding classes. Further, the changing patterns of cropping, tools, and implement and input use were also probed into. Tribal development is probed in terms of indicators of living conditions of the tribal households such as annual household income, annual household expenditure and household saving, and investments and their patterns.

Methodology

This study is cross sectional in nature and descriptive in design. It is mainly based on the primary data collected through a pretested structured household interview schedule in two sample villages. In addition, participatory methods, viz., timeline, social map, and seasonal diagram were used to understand the social and ecological context of sample villages and cultivation practices.

The study adopted a multistage sampling procedure to select districts, blocks, villages and households. The study was conducted in Aizawl and Kolasib districts. They were purposively selected in view of the fact that they constitute a majority of the rural households in Mizoram. In Aizawl district, one representative village predominantly occupied by settled agriculturists were chosen. And in Kolasib district, one representative village predominantly relying on shifting cultivation was also chosen purposively. In each of the villages, the lists of very poor, poor and non-poor households were collected from the village council presidents. In each of the categories, using systematic random sampling, households were proportionately selected.

proportions were used. Apart from them 't' test and Karl Pearson's Product moment correlation were used to draw inferences.

The Setting : Profile of Study Villages

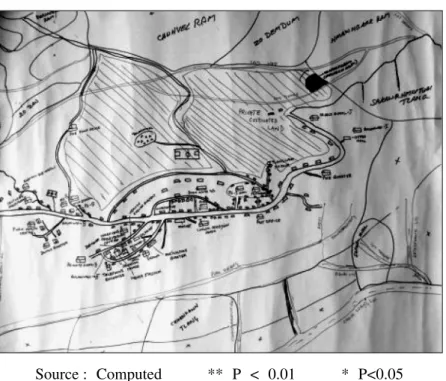

For profiling the village communities, key informant interviews and participatory research methods as well as available secondary data with the village council were mainly used. Key informants interviews at tea stalls and Bazars were conducted to have a better understanding of the two communities and agricultural practices. Participatory research methods of social map and seasonal calendar were used to understand the spatial and temporal features of the two villages. Social Mapping exercise was conducted in the two villages at Lungdai and Sesawng. The village elders and leaders of the community based organisations were the participants. The map was prepared by the local people on 7th

June 2010 at Lungdai, which is a settled agricultural village, and on 14th

June 2010 at Sesawng, which is shifting cultivators' village. The members were 13 members at Sesawng and 12 members at Lungdai. Different age groups from adults to elderly, both men and women, provided rich information. Seasonal diagrams of two villages were also prepared by the key informants. They were prepared by the local people on 7th

June 2010 at Lungdai and on 14th June 2010 at Sesawng. The original table was written in the Mizo language which was translated into English.

Lungdai: A Settled Agriculturists Village

Lungdai Village is part of Kolasib District. It was established in 1908. It is located 30 km north of Aizawl. The proportion of female population was almost the same as male. In this village a few denominations were professed, of which the Presbyterian Church is the main denomination.

We could observe the households' access to government services in the community indicating that people in community have higher access to the government services and banking system. But there was no educational institution above the matriculation level which contributes to the lower educational status of its people.

cultivation. Most of the lands were under Land Settlement Certificate and Periodic land pass from the village council. Squash was the main crop cultivated in the village for which the community was well known in Aizawl. Most of the cultivation and crops were commercialised (See figure1).

Sesawng: The Shifting Cultivators' Village

Sesawng is an old village where Mizos have lived for many generations. It is a place where Lalburha, one of the famous Mizo chiefs along with other seven village chiefs, mobilised people to oppose the invasion of the British. As it is 48 km away north of the heart of Aizawl, the capital of Mizoram, less access to government services was observed (See figure2).

It is a traditional village where most of the villagers depend on shifting cultivation for their subsistence. Although some few semi-settled cultivators were observed, most of them failed because of the lack of irrigation. Shifting cultivation is still widely practiced, while a few people practice settled agriculture and grow crops like banana. Most of the lands near the settlement were owned by the rich people from Aizawl.

Results and Discussion

In the previous section, the profiles of the villages were presented. In this light, this section presents the discussion of the results of analysis of quantitative data collected through the field survey. This section is presented in terms of three broad sections, viz., patterns of agrarian structure, tribal development and pattern of relationship between agrarian structure and tribal development.

i. Patterns of Agrarian Structure

To understand the changes in the agrarian structure, three sets of indicators, viz., pattern of land possessed, cropping pattern, and livestock ownership, were analysed and the results are discussed in this section.

Patterns of Land Possessed

various types of land passion and among the size of land holding classes. Four types of land possession could be observed in context of Mizoram which form a continuum of community ownership to complete private ownership. They are Common Land, Temporary Pass (VC Pass), Periodic Land Pass (PLP), and Land Settlement Certificate (LSC is equivalent to Patta land) (Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj 2008).

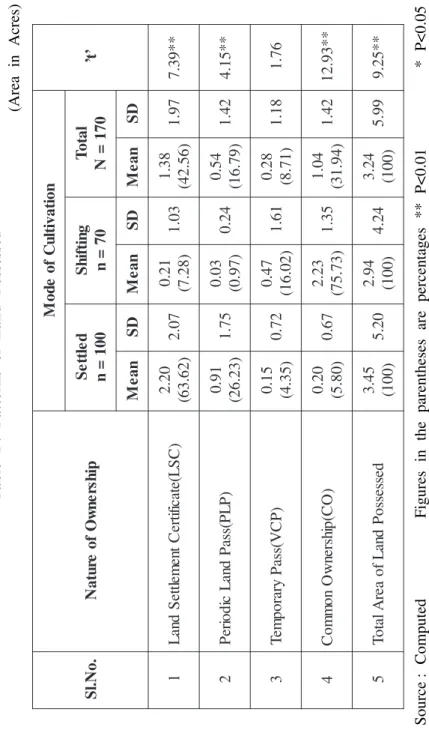

The results indicate that the cultivators in the settled villagers have predominantly switched over to settled cultivation from shifting cultivation, while those in the other village were practicing shifting cultivation (See table 1). Most of the lands possessed by settled cultivators are under LSC (64%) and some are still under PLP (26%). On the other hand, most of the lands possessed by shifting cultivators are under common land (76%).

As a result of the switchover from shifting cultivation to settled agriculture, the area of land possessed on an average by a household has slightly increased, but significantly. The mean size of total land holding among shifting cultivators worked out to be 3.5 acres while it was 2.9 acres in the case of shifting cultivators. This difference was statistically significant. Similarly, the area of land under LSC, and PLP were slightly greater in case of settled cultivators as compared to shifting cultivators. On the other hand, the area under common ownership was greater in the case of shifting cultivators as compared to settled cultivators. While in the area under VC pass, no significant difference could be observed.

Size of Land Holding

Distribution of households across the size of land holding classes is another indicator taken for understanding the changes in the land possession. The size of land holding is categorised into three classes such as marginal (Below 2 acres), Small (2-5 Acres), and Medium (5-10 Acres).

The proportion of small farmers and medium farmers is greater among the settled cultivators as compared to shifting cultivators. On the other hand, the proportion of marginal farmers is greater among the shifting cultivators as compared to settled cultivators. The size of land possessed by the settled agriculturalists (3.4 Acres) is significantly greater than that of the shifting cultivators (2.94 Acres). The mean land holding size is significantly greater among the settled agriculturalists (See table 2).

Interestingly, the switchover from shifting cultivation resulted in embourgeoisement but has not resulted in emergence of large or very large farmers. There was not a single large farmer found in both the villages. But our discussion with the key informants indicated that some rich people from Aizawl city own large areas of land in this village which shows emergence of absentee land ownership.

Cropping Pattern

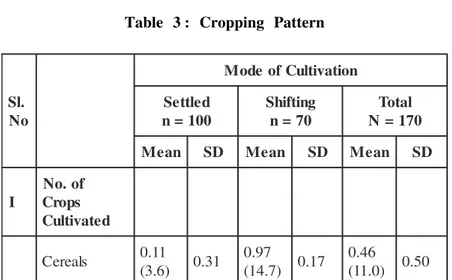

Cropping pattern is the second set of indicators chosen for assessing the nature of agrarian change. Crops cultivated were classified into seven types, viz., Cereals, Pulses, Oilseeds, Vegetables, Fruit, Trees, and Other Commercial crops as in an earlier study in Mizoram by Zaitinvawra and Kanagaraj (2008).

The number of crops and area under different crops were the two indicators analysed to understand the changes in the cropping pattern. The results indicate that the switchover from shifting cultivation to settled agriculture resulted in mono-cropping and commercialisation of cropping pattern.

The indicator area under cultivation also reveals a similar picture of cropping pattern. Most of the area under settled agriculture is used for cultivating vegetables while that of shifting cultivators was under cereals. The main crop is Squash. As the settled agriculturalist move from diversification of crops to mono cropping, they started to look after only one or two crops concentrating their effort and skills to increase production. The settled agriculturalist grow more commercial crops such as coffee, Zawngtah, Hmunphiah, etc., than cereals and the area used for this was also larger than for other crops. The shifting cultivators do not grow any commercial crops in particular, but they consume most of their products and also sell the surplus.

In the cropping pattern, two main shifts were observed. While moving from shifting cultivation to settled agriculture the patterns of cropping moved from crop diversity to mono cropping and also from subsistence to commercialisation of crops (See table 3).

Patterns of Livestock Ownership

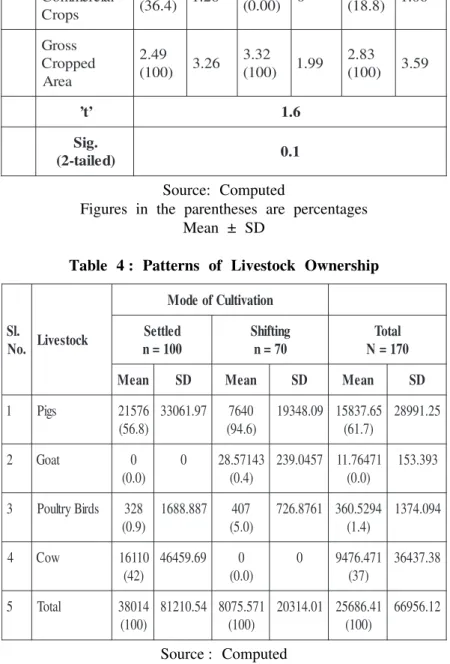

Livestock rearing is one of the sources of livelihood in tribal communities from time immemorial. In the context of Mizoram, it was customary for the Mizos to rear only pigs and cow rearing was unknown. In this subsection, the differential patterns of livestock ownership between the shifting cultivators and settled agriculturists is analysed and discussed. The livestock owned among the shifting and settled agriculturalist were of four types, viz., Pig, Goat, Poultry Bird and Cow (See table 4).

Pigs constitute the predominant form of livestock owned by both settled cultivators and shifting cultivators. However, the value of pigs owned is greater among the settled agriculturalists (Rs 21,576) than that of shifting cultivators (Rs 7,640). Yet the share of the value of pigs in the total value of livestock is greater among the shifting cultivators (95%) as compared to the settled cultivators (57%).

Cow rearing which was unknown in traditional Mizo society has emerged among the settled cultivators, while none among the shifting cultivators rear cows. The mean value of the cows owned by the settled agriculturists was worked out to Rs 16,110 which constitutes 42 per cent of the share of total value of livestock owned by them.

For some of the settled agriculturalists, livestock rearing has become the main occupation and cultivation has become secondary. This clearly shows that moving from shifting cultivation to settled agriculture results in the diversification of occupation.

ii. Tribal Development: Living Conditions

To assess the tribal development, the pattern and level of Annual Household Income, Annual Household Expenditure, Households' Savings and Debt as well as Housing were analysed.

Household Income

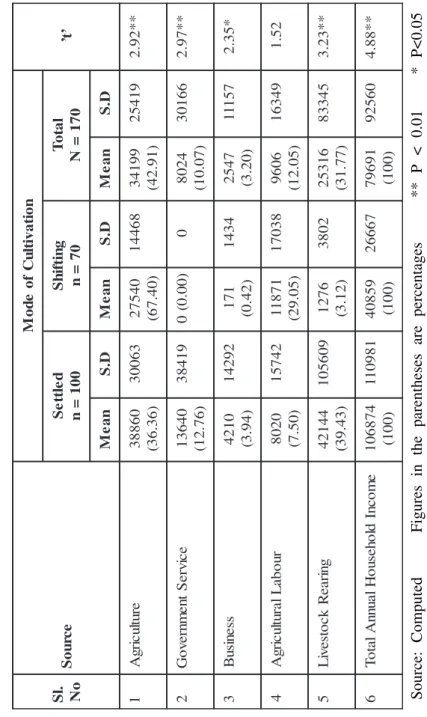

Household Income is the first indicator of standard of living. It is analysed in terms of source pattern and level. Agriculture, Government Service, Business, Agriculture labour and Livestock Rearing constitute the sources of income in the study area (See table 5). The results of analysis of pattern of annual income clearly demonstrate that switchover from shifting cultivation to settled-agriculture has resulted in diversification of income for Mizo households. The main source of household income among the shifting cultivators was Agriculture (67%), while among the settled agriculturalists the main sources of income were Livestock Rearing (39%) and Agriculture (36%).

from all the sources except agricultural labour. Total average annual household income of the settled cultivators (Rs 106,874) was significantly higher than that of the settled cultivators (Rs 40,859). Likewise, the mean annual household income from agriculture was significantly greater among the settled cultivators (Rs 38,860) as compared to those of shifting cultivators (Rs 27,540). Similarly, income from government service, business and livestock rearing were significantly greater for the settled cultivators as compared to the shifting cultivator households.

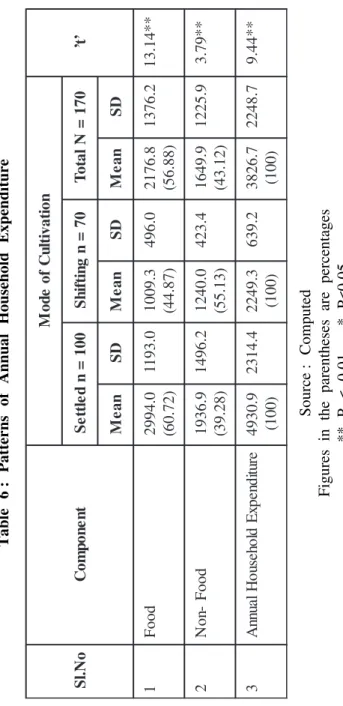

Household Expenditure

The second indicator of standard of living is annual household expenditure. The differences in the pattern and level of household expenditure between shifting cultivators and settled agriculturists are discussed here. Annual household expenditure is classified as food and non-food components (See table 6). The major share of annual household expenditure was incurred on food in the case of settled cultivators (61%) while most part of the expenditure of the shifting cultivators was spent on non-food items (55%). This is contrary to the prediction of Engel's law according to which as income of household increases, the proportion of income spent on food declines, even though the actual expenditure on food increases. This could be attributed to the fact that the shifting cultivators undervalue their produce used for their own consumption.

In spite of that, the annual household expenditure of the settled cultivators (Rs 4,930) was significantly greater as compared to shifting cultivators (Rs 2,249). On both the components of household expenditure, viz., food and non-food, the settled agriculturists on an average incur greater expenditure as compared to the shifting cultivator households.

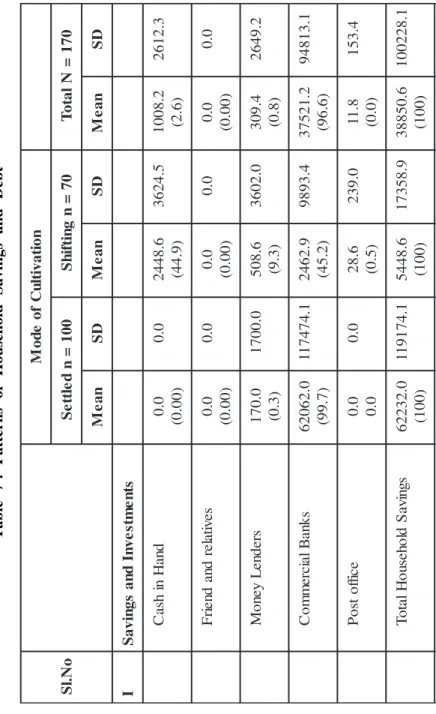

Household Savings and Debt

cultivators, most of the household savings were in the form of deposits in the Commercial banks (99%) while savings of the shifting cultivators were equally dived between cash in hand (45%) and savings in commercial banks(45%). Similarly, most of the debt of the settled agriculturist households was owed to the commercial banks (100%) while most of the loans of the shifting cultivators were borrowed from friends and relatives (67%).

Similar to the levels of income and expenditure, in the levels of household savings and debt also the settled agriculturalists were better of as compared to the shifting cultivators. The total household savings of the settled cultivators (Rs 62,232) was far greater as compared to that of shifting cultivators (Rs 5,448). Similarly, though meagre in quantity, the household debt of the settled cultivators (Rs 4,600) was higher as compared to that of the shifting cultivators (Rs 121).

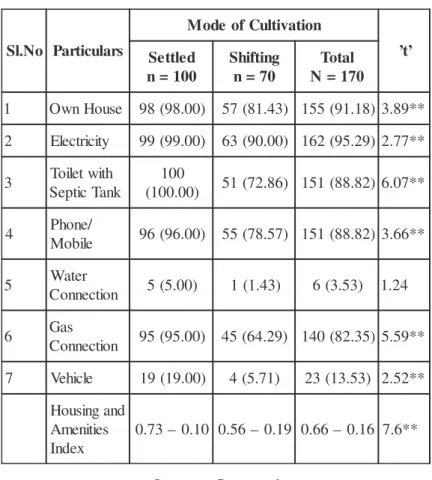

Housing and Amenities

Housing and amenities constitute the last set of indicators analysed to gauge the differences in the living conditions of the settled and shifting cultivators. They are ownership of house, electricity, toilet with septic tank, phone/mobile, water connection, gas connection, and vehicle (two or four wheeler). In almost all of these indicators the greater proportion of settled cultivators had possession of them (See table 8). Though a majority of the households of shifting cultivators own houses, have electricity, toilet with septic tank, phone and gas connection, the proportion of the settled cultivators possessing them is greater. The housing and amenities index which is a composite of proportion of all these indicators is also significantly greater for settled cultivators (0.73) as compared to shifting cultivators (0.56). Interestingly, about 73 per cent of the settled cultivators have access to all these facilities or amenities while only 56 per cent of the shifting cultivators have all of these.

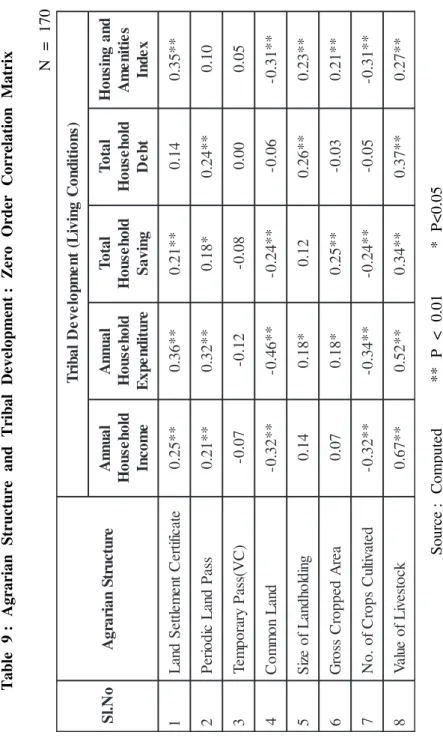

development, i.e. improvement in the living conditions the Karl Pearson's Coefficients of correlation were used. Apart from elements of agrarian structure such as area under Land Settlement Certificate area under Periodic Land Pass, area under Temporary Pass (VC), area under Common Land and Size of Landholding, also Gross Cropped Area, Number of Crops Cultivated and Value of Livestock were assessed for correlation with the indicators of living conditions such as Annual Household Income, Annual Household Expenditure, Total Household Saving, Total Household Debt, Housing and Amenities Index (See table 9).

The results of correlation analysis clearly reveal that the switchover from shifting cultivation to settled cultivation results in improvement in the tribal living conditions and contributes to tribal development. Among the indicators of change in agrarian structure, viz., Area under Land Settlement Certificate, Periodic Land Pass, and size of land holding have significant positive relationship with most of the indicators of tribal development viz., Annual Household Income, Household Expenditure, total Household Saving, total Household Debt, and Housing & Amenities Index. On the other hand, the area under common land has significant positive relationship with most of the indicators of tribal development(see table 9).

A probe further into the relationship between the indicators of change in cropping reveals that as the gross cropping area increased, the living conditions have improved. Further, the switch over from multi cropping to mono cropping has also resulted in improvement in the living conditions of tribal households. There were significant positive relationship between gross cropped area and annual household expenditure, total household saving, and housing and amenities index. On the other hand, there is a significant negative relationship between number of crops cultivated by the farmer households and their living conditions in terms of increase in annual household expenditure, household savings, and housing and amenities (see table 9).

expenditure, household saving, household debt and household amenities index are positive and significant(see table 9).

Conclusion

The study clearly shows that the switchover from shifting cultivation to settled cultivation results in improvement in the living conditions in Mizoram. The switchover to settled cultivation has also resulted in commercialisation and emergence of mono cropping with a single vegetable crop. Further, the improvement in living conditions was not only due to commercialisation in cropping pattern but also because of farm diversification, especially the emergence of livestock rearing which was not popular among the Mizos in the past and even today in other parts of the state. One disturbing finding is that though the income from agriculture has increased, it is not too great. Another problem is that the mono cropping pattern that emerged in the wake of settlement. In case of failure of perishable crops such as squash whether the income of cultivators will be sustainable? Further, if all over Mizoram such switchover to settled cultivation and mono cropping happens, whether there will be adequate markets for all the produce. The implication of the study is that while promoting settled cultivation, the government needs take adequate measures to promote crop diversification, farm diversification as well as better transportation and markets for the agricultural produce. It also needs to restrict allotment of land to those who live in the particular village rather than to the rich people from other areas.

References

Athreya, V. Djurfeld, G. Lindberg, (1990), Barriers Broken : Production Relation and Agrarian Change, Social Scientist, 14(5), 3-14. Basant, R. (1987), Agriculture Technology and Employment in India :

A Survey of Recent Research, Economic and Political Weekly, 22(32), 1348-1364.

Byres, T. (1981), The New Technology, Class Formation, Class Action in the Indian Countryside, Journal of Peasant Studies, 8(4), 405-454.

Darlong, V. T. (2004), To Jhum or not to Jhum : Policy Perspective on Shifting Cultivation, Guwahati : The Missing Link.

Eswaraiah, G. (2003), Challenges of Rural Eco System in India, Employment News, 27(50), 1-3.

Gadgil, M. N. Prasad, N. and Ali, R. (1983), Forest Management in India : A Critical Review, Social Action, 33(2), 127-155.

Government of India, (2007), Tenth Five Year Plan, New Delhi : Planning Commission.

Government of Mizoram, (2004), Statistical Hand Book, Aizawl : Department of Economic and Statistics.

Harris, J. (1982), Capitalism and Peasant Farming : Agrarian Structure and Ideology in Northern Tamil Nadu, Bombay : Oxford University Press.

Joshi, P. C. (1969), Agrarian Social Structure and Social Change, Sankhya-: The Indian Journal of Statistics, Series B, 31(3/4), 479-490.

Kanagaraj, E. (2005), Human Development and Social Exclusion of Scheduled Tribes in Tamil Nadu, Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Annamalai Nagar : Annamalai University.

Kanagaraj, E. (2014), Human Development and Social Exclusion among Primitive Tribes in India, Deutschland / Germany : Lambert Academic Publishing.

Karuppaiyan, E. (1990), Alienation of Tribal Lands in Tamil Nadu. Economic & Political Weekly, 25 (22), 1185-1186.

Manivannan, S. (1989), A Study of Tribal Poverty and Indebtedness with Special Reference to Malayali Tribe of South Arcot Kalrayan Hills, Tamil Nadu. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Annamalai Nagar : Anamalai University.

Mukherjee, R. (1949), The Economic Structure and Social Life in Six Villages of Bengal, American Sociological Review, 14(3), 415-425. Ninan, K.N. (1992), Economics of Shifting Cultivation in India, Economic

and Political Weekly, 27 (13), 67-91.

Rajarathnam, T. N. and Guruswami, P. A. (1987), Taking Technology to Tribal People and Communities : Report of the Phase I (Survey) of the Project, Coimbatore: Sri Ramakrishna Mission Vidyalaya Arts College.

Ramachandran, S. (2012), Tribal Development Programmes in India, New Delhi: Abhijeet Publications.

Neolithic. In R. Mercer (Ed), Farming Practice in the British Prehistory, Edinburgh : Edinburgh University Press.

Sachidananda, (1989), Shifting Cultivation in India, New Delhi : Concept Publishing Company.

Saravanan, V. (2001), Tribal Land Alienation in Madras Presidency during the Colonial Period, 1792-1947, Review of Development and Change, 6(1), 73-104.

Sen, S. (1992), Tribes of Mizoram : Description Ethnology and Bibliography, New Delhi : Gian Publishing House.

Shah, A. (2013), The Agrarian Question in a Maoist Guerrilla Zone : Land, Labour and Capital in the Forests and Hills of Jharkhand, India, Journal of Agrarian Change, 13(3), 424-450.

Thangchungnunga, (1997), Shifting Cultivation and Emerging Pattern of Change in Land Relation, In L.K. Jha (Ed), Natural Resource Management Mizoram, New Delhi: APH Publishing Corporation. Thorner, D. (1968), Predatory Capitalism in Indian Agriculture, Economic

and Political Weekly, 3 (43), A3-A4.

Table 1

: Patterns of Land Possessed

(Area in Acres)

. o N.l S pi hs r e n w O f o er ut a N n oit a vit l u C f o e d o M ’t’ d elt t e S 0 0 1 = n g nit fi h S 0 7 = n l at o T 0 7 1 = N n a e M D S n a e M D S n a e M D S 1 ) C S L( et aci fit re C tn e mel tt e S dn a L 0 2. 2 ) 2 6. 3 6( 7 0. 2 1 2. 0 ) 8 2. 7( 3 0. 1 8 3. 1 ) 6 5. 2 4( 7 9. 1 * * 9 3. 7 2 ) P L P( ss a P dn a L ci d oir e P 1 9. 0 ) 3 2. 6 2( 5 7. 1 3 0. 0 ) 7 9. 0( 4 2. 0 4 5. 0 ) 9 7. 6 1( 2 4. 1 * * 5 1. 4 3 ) P C V( ss a P yr ar o p me T 5 1. 0 ) 5 3. 4( 2 7. 0 7 4. 0 ) 2 0. 6 1( 1 6. 1 8 2. 0 ) 1 7. 8( 8 1. 1 6 7. 1 4 ) O C( pi hs re n w O n o m m o C 0 2. 0 ) 0 8. 5( 7 6. 0 3 2. 2 ) 3 7. 5 7( 5 3. 1 4 0. 1 ) 4 9. 1 3( 2 4. 1 * * 3 9. 2 1 5 de ss es s o P dn a L f o ae r A la t o T 5 4. 3 ) 0 0 1( 0 2. 5 4 9. 2 ) 0 0 1( 4 2. 4 4 2. 3 ) 0 0 1( 9 9. 5 * * 5 2. 9 Source

Table 2 : Size of Land Holding . l S . o N f o e z i S g n i d l o h d n a L n o i t a v i t l u C f o e d o M l a t o T 0 7 1 = N d e l t t e S 0 0 1 = n g n i t f i h S 0 7 = n

1 Marginal(Below2

) s e r c A 1 3 ) 0 0 . 1 3 ( 7 3 ) 6 8 . 2 5 ( 8 6 ) 0 0 . 0 4 (

2 Small(2-5Acres) 54

) 0 0 . 4 5 ( 8 2 ) 0 0 . 0 4 ( 2 8 ) 4 2 . 8 4 (

3 Medium(5-10

) s e r c A 5 1 ) 0 0 . 5 1 ( 5 ) 4 1 . 7 ( 0 2 ) 6 7 . 1 1 ( l a t o

T 100

) 0 0 1 ( 0 7 ) 0 0 1 ( 0 7 1 ) 0 0 1 ( f o e z i S n a e M g n i d l o h d n a

L 3.45–2.14 2.94–1.84 3.24–2.03

Source : Computed

Figures in the parentheses are percentages

Mean ± SD

Table 3 : Cropping Pattern

. l S o N n o i t a v i t l u C f o e d o M d e l t t e S 0 0 1 = n g n i t f i h S 0 7 = n l a t o T 0 7 1 = N n a e

M SD Mean SD Mean SD

I f o . o N s p o r C d e t a v i t l u C s l a e r e

C 0.11

) 6 . 3

( 0.31

7 9 . 0 ) 7 . 4 1

( 0.17

6 4 . 0 ) 0 . 1 1

s e s l u

P 0.00

) 0 0 . 0

( 0.00

0 0 . 0 ) 0 0 . 0

( 0.00

0 0 . 0 ) 0 0 . 0

( 0.00

s d e e s l i

O 0.32

) 4 . 0 1

( 0.58

6 3 . 0 ) 4 . 5

( 0.48

4 3 . 0 ) 9 . 7

( 0.54

s e l b a t e g e

V 1.52

) 2 . 9 4

( 0.90

6 1 . 5 ) 8 . 7 7

( 1.07

2 0 . 3 ) 3 . 1 7

( 2.04

s t i u r

F 0.37

) 0 . 2 1

( 0.77

4 1 . 0 ) 2 . 2

( 0.60

8 2 . 0 ) 5 . 6

( 0.71

s p o r C e e r

T 0.24

) 8 . 7

( 0.67

0 0 . 0 ) 0 0 . 0

( 0.00

4 1 . 0 ) 3 . 3

( 0.53

r e h t O l a i c r e m m o C s p o r C 3 5 . 0 ) 2 . 7 1

( 0.56

0 ) 0 0 . 0 ( 0 1 3 . 0 ) 4 . 7

( 0.50

l a t o

T 3.09

) 0 0 1

( 3.25

3 6 . 6 ) 0 0 1

( 2.32

4 2 . 4 ) 0 0 1

( 4.32

I

I AreaUnder n o i t a v i t l u C s l a e r e

C 0.24

) 7 . 9

( 0.77

0 4 . 2 ) 3 . 2 7

( 1.13

3 1 . 1 ) 9 . 9 3

( 1.42

s e s l u P 0 ) 0 0 . 0 ( 0 0 ) 0 0 . 0 ( 0 0 ) 0 0 . 0 ( 0 s d e e S l i

O 0.27

) 7 . 0 1

( 0.50

6 2 . 0 ) 0 . 8

( 0.39

6 2 . 0 ) 4 . 9

( 0.46

s e l b a t e g e

V 1.58

) 4 . 3 6

( 0.98

1 6 . 0 ) 3 . 8 1

( 0.25

8 1 . 1 ) 6 . 1 4

( 0.90

s t i u r

F 0.28

) 1 . 1 1

( 0.62

5 0 . 0 ) 5 . 1

( 0.21

8 1 . 0 ) 4 . 6

( 0.51

s e e r

T 0.13

) 2 . 5

( 0.39

0 0 . 0 ) 0 0 . 0

( 0.00

8 0 . 0 ) 7 . 2

r e h t O l a i c r e m m o C s p o r C 1 9 . 0 ) 4 . 6 3

( 1.26

0 ) 0 0 . 0 ( 0 3 5 . 0 ) 8 . 8 1

( 1.06

s s o r G d e p p o r C a e r A 9 4 . 2 ) 0 0 1

( 3.26

2 3 . 3 ) 0 0 1

( 1.99

3 8 . 2 ) 0 0 1

( 3.59

’ t

’ 1.6

. g i S ) d e l i a t -2

( 0.1

Source: Computed

Figures in the parentheses are percentages Mean ± SD

Table 4 : Patterns of Livestock Ownership

.l S

. o

N Livestock

n o i t a v i t l u C f o e d o M d e l t t e S 0 0 1 = n g n i t f i h S 0 7 = n l a t o T 0 7 1 = N n a e

M SD Mean SD Mean SD

1 Pigs 21576

) 8 . 6 5 ( 7 9 . 1 6 0 3

3 7640

) 6 . 4 9 ( 9 0 . 8 4 3 9

1 15837.65

) 7 . 1 6 ( 5 2 . 1 9 9 8 2

2 Goat 0

) 0 . 0 (

0 28.57143

) 4 . 0 ( 7 5 4 0 . 9 3

2 11.76471

) 0 . 0 ( 3 9 3 . 3 5 1

3 PoutlryBrids 328

) 9 . 0 ( 7 8 8 . 8 8 6

1 407

) 0 . 5 ( 1 6 7 8 . 6 2

7 360.5294

) 4 . 1 ( 4 9 0 . 4 7 3 1

4 Cow 16110

) 2 4 ( 9 6 . 9 5 4 6 4 0 ) 0 . 0 (

0 9476.471

) 7 3 ( 8 3 . 7 3 4 6 3

5 Total 38014

) 0 0 1 ( 4 5 . 0 1 2 1

8 8075.571

) 0 0 1 ( 1 0 . 4 1 3 0

2 25686.41

) 0 0 1 ( 2 1 . 6 5 9 6 6

Source : Computed

Table 5

: Patterns of Annual Households Income

.l

S oN

e cr u o S n oi t a vi tl u C f o e d o M ’t’ d el tt e S 0 0 1 = n g ni tfi h S 0 7 = n l at o T 0 7 1 = N n a e M D. S n a e M D. S n a e M D. S 1 er utl u cir g A 0 6 8 8 3 ) 6 3. 6 3( 3 6 0 0 3 0 4 5 7 2 ) 0 4. 7 6( 8 6 4 4 1 9 9 1 4 3 ) 1 9. 2 4( 9 1 4 5 2 * * 2 9. 2 2 e ci vr e S t n e m nr e v o G 0 4 6 3 1 ) 6 7. 2 1( 9 1 4 8 3 ) 0 0. 0( 0 0 4 2 0 8 ) 7 0. 0 1( 6 6 1 0 3 * * 7 9. 2 3 ss e ni s u B 0 1 2 4 ) 4 9. 3( 2 9 2 4 1 1 7 1 ) 2 4. 0( 4 3 4 1 7 4 5 2 ) 0 2. 3( 7 5 1 1 1 * 5 3. 2 4 r u o b a L l ar utl u cir g A 0 2 0 8 ) 0 5. 7( 2 4 7 5 1 1 7 8 1 1 ) 5 0. 9 2( 8 3 0 7 1 6 0 6 9 ) 5 0. 2 1( 9 4 3 6 1 2 5. 1 5 g nir a e R k c ot s e vi L 4 4 1 2 4 ) 3 4. 9 3( 9 0 6 5 0 1 6 7 2 1 ) 2 1. 3( 2 0 8 3 6 1 3 5 2 ) 7 7. 1 3( 5 4 3 3 8 * * 3 2. 3 6 e m o c nI dl o h es u o H l a u n n A l at o T 4 7 8 6 0 1 ) 0 0 1( 1 8 9 0 1 1 9 5 8 0 4 ) 0 0 1( 7 6 6 6 2 1 9 6 9 7 ) 0 0 1( 0 6 5 2 9 * * 8 8. 4

Table 6

: Patterns of Annual Household Expenditure

o N.l S t n e n o p m o C n oit a vit l u C f o e d o M ’t’ 0 0 1 = n d elt t e S 0 7 = n g nit fi h S 0 7 1 = N l at o T n a e M D S n a e M D S n a e M D S 1 d o o F 0. 4 9 9 2 ) 2 7. 0 6( 0. 3 9 11 3. 9 0 0 1 ) 7 8. 4 4( 0. 6 9 4 8. 6 7 1 2 ) 8 8. 6 5( 2. 6 7 3 1 * * 4 1. 3 1 2 d o o F -n o N 9. 6 3 9 1 ) 8 2. 9 3( 2. 6 9 4 1 0. 0 4 2 1 ) 3 1. 5 5( 4. 3 2 4 9. 9 4 6 1 ) 2 1. 3 4( 9. 5 2 2 1 * * 9 7. 3 3 er uti dn e px E dl oh es u o H la un n A 9. 0 3 9 4 ) 0 0 1( 4. 4 1 3 2 3. 9 4 2 2 ) 0 0 1( 2. 9 3 6 7. 6 2 8 3 ) 0 0 1( 7. 8 4 2 2 * * 4 4. 9 Source : Computed

Figures in the parentheses are percentages