Influence of Parental Gender and Self-Reported Health and Illness on

Parent-Reported Child Health

Elizabeth Waters, GDBIS, MPH, DPhil (Oxon)*; Jodie Doyle, BN, MPH*; Rory Wolfe, PhD§; Martin Wright, MD, MPH‡; Melissa Wake, MBChB, MD*; and Louisa Salmon, BA (Hons)*

ABSTRACT. Background. Although there is clear evi-dence of the influence of parental factors on child health outcomes, the influence of parental perceptions of their health and illness on the reporting of child health re-mains primarily unknown.

Objectives. To examine relationships between par-ents’ reporting of their own health and illness with the reporting of their children’s health and illness.

Method. We surveyed parents of a representative population-based sample of children aged 5 to 18 years. One parent of each child completed a written question-naire including the Child Health Questionquestion-naire, a sub-jective measure of functional health and well-being, and an assessment of self-reported parental health and ill-ness. Logistic regression models were used to examine relationships between parent and child health and ill-ness.

Main Results. 5340 parents responded (86% mothers, 14% fathers). After adjusting for confounding effects, parents self-reporting poor health had increased odds of reporting their children with poor health (odds ratio: 7.5), although the effect was modified by parent gender. There were increased odds of mothers with self-report-ing poor global health reportself-report-ing their children with poor global health and illness (odds ratio: 9.0 and 2.5, respec-tively) that were not observed for fathers.

Conclusions. A mother’s self-reported health is strongly associated with her reporting of her child’s health; this was not observed for fathers. These results suggest that parental gender should be considered as a mediating factor in the reporting of child health.

Pediatrics 2000;106:1422–1428; self-report, parent, child, health status, measurement.

ABBREVIATIONS. HOYVS, Health of Young Victorians Study; CHQ, Children’s Health Questionnaire; GGH, Global General Health.

P

arents are frequently asked to assess and report on the health of their children in clinical care, population health surveys and health outcome research, particularly for young children or children with communication disabilities. There are causal relationships which clearly demonstrate the influ-ence of parental factors on child health outcomes such as antenatal exposures,1,2environmental3,4and genetic determinants,5 sociodemographic factors,6 –9 and parental behaviors.10 –12Yet the effect of parental health and illness on parental reporting of child health remains unclear. Research in this field is fre-quently narrowed to studies with small numbers of children with specific illnesses, the study design of which is often inadequately powered or designed to examine the effects of potential bias and confound-ing. Research has begun to examine whether a par-ent’s perception of their own health or the existence of an illness affects their reporting of their child’s health, yet uncertainty remains regarding whether the associations observed remain the same for moth-ers and fathmoth-ers.13It seems likely that socioeconomic status, parental health, and gender may influence parent’s reports of their children’s health. Two studies (a clinical study of infants and a population survey of young children aged 2 to 4 years) have examined the influence of parental socioeconomic status and maternal depres-sion on their reports of child health.14,15Each study concluded that mothers with an illness were not more likely to view their child’s health negatively, albeit those who perceived their own health as poor were likely to report their infant’s health as poor,14 and parents (in this case, mothers) were able to ef-fectively discriminate between their own health and that of their child. In another large population study, primary school aged children were found to have poorer health in families where parents reported or suffered poor health using both subjective and stan-dard illness indicators.16In the parallel field of child development, researchers have concluded that par-ents across sociodemographic groups accurately and reliably report their child’s developmental age,17,18 developmental problems,19 and behavioral prob-lems,19,20 although these studies did not measure parental health or its influence.

Variations do exist between mothers and fathers in their assessment of child behavior,21–23parental cop-ing with children with chronic illness,24 –28 and the effect of child illness on parent and family

function-From the *Centre for Community Child Health, University of Melbourne, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia; the ‡Department of Pae-diatrics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; Health Services Research Unit, Department of Public Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; and the §Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics Unit, Royal Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. Received for publication Aug 27, 1999; accepted Mar 27, 2000.

Reprint requests to (E.W.) Child Public Health, Research and Policy Unit, Centre for Community Child Health, University of Melbourne, Royal Chil-dren’s Hospital, Victoria 3052 Australia. E-mail: waters3@cryptic.rch. unimelb.edu.au

ing,29,30 whereas other studies have not shown an influence of gender.31,32A more recent study of chil-dren with musculoskeletal problems aimed to eval-uate the influence of parental health on reporting of child outcomes, and concluded that the health and well-being of the parent is a critical factor in the parent’s perception of how well the child is doing.33 In sum, the results of research to date remain inad-equate in their ability to provide answers which are generalizable to primary pediatric care or population epidemiology. Questions remain about whether mothers and fathers with similar sociodemographic circumstances and health status differ in their report-ing of their child’s health and illness, and whether child factors such as age or gender influence these results. Newly available multidimensional measures of child health also provide an important opportu-nity to assess whether relationships observed hold across multiple domains of emotional, social and physical health.

In this study we aimed to examine whether parent gender, illness or perception of their health, influ-ences reporting of their child’s health, illness and well-being. Data were drawn from a population-based community study of the health of children aged 5 to 18 years. The parental responses provided sufficiently large samples of both mothers and fa-thers to enable analyses to be stratified by gender. We used standardized and pre-validated subjective measures of child and adult health, and child func-tional health and well-being.

METHODS

The data were collected as part of the Health of Young Victo-rians Study (HOYVS), an epidemiological study of the health and well-being of children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 years in Victoria, Australia (described in detail elsewhere).34 Ethics

ap-proval for the study was obtained from the Royal Children’s Hospital Ethics in Human Research Committee, Victorian Gov-ernment Department of Education, Catholic Directorate of Educa-tion and in principle by the Independent Schools AssociaEduca-tion. The study was conducted between July and December 1997.

Sample

To obtain a representative sample of school children in Victoria, Australia, all relevant schools were stratified by school sector (government, Catholic, and independent). Within each of the 48 schools selected, one intact class of children was randomly se-lected at each year level. Analyses were weighted to account for this two-stage cluster sampling, allowing the results to be gener-alized to all school children in Victoria.

Data Collection

One parent of each participating child completed a written questionnaire that consisted of parent sociodemographic vari-ables, a parent global health item,35child and parent illnesses (Fig

1), and the parent-report Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ PF50)36(which includes a single global child health item). Parent

proxies were asked to complete the questionnaire in case a parent was unavailable.

The study also collected adolescent reports of their own health using a self-reported CHQ. The aim of this present study, how-ever, was to examine the association of parental health on parental reports for the age group of 5 to 18 years. Analysis of the relation-ships between adolescent self-report and parent-report is limited to ages 12 to 18 years, and is beyond the scope of this paper (it is currently being analyzed in a subsequent doctoral thesis).

Measures

The CHQ PF50 is a standardized measure of subjective func-tional health and well-being for children aged 5 to 18 years.36It

has been used in the assessment of child health and well-being in representative populations of children in the United States,36

Aus-tralia,37Ireland, the Netherlands, and in children with chronic

illness.38Previously reported analyses of data from the HOYVS

have indicated that the CHQ PF50 is a reliable and valid instru-ment for use in Australia,34,37 and has an approximate reading

comprehension level of Grade 6.37It contains 50 items measuring

domains of physical and emotional health, grouped into 2 single and 11 multi-item scales that use a Likert-type scaling mechanism to measure poor to good health (see Table 1). Two additional single items are contained within the multi-item scales and can be used to represent an independent concept of Global General Be-havior and Global General Health (GGH). Each multi-item scale score is calculated by totaling contributions from each item and then scaling the total score to provide values from 0 (representing worst health) to 100 (representing best health). The single GGH item was used in addition to the complete CHQ to measure parental perception of their child’s global health. Used in its entirety, the CHQ provides scales that encompass functioning, social roles, emotional health, physical health, and family func-tioning (activities and cohesion).

Parent perception of their own global health was measured using an identical question, the GGH item from the shortened 6-item adult self-reported subjective measure of functional heath status, the SF6, derived from the Short Form 36.35Both the child

and adult GGH items use a 5-item, 5-response scale that measures from excellent to poor (Fig 1). For the analyses in this paper, responses for children and their parents were dichotomized into poor health (fair/poor categories) and good health (good/very good/excellent categories), as with previous studies.15,39 – 41Child

and parent illness were indicated by a yes response to any of a list of various medical conditions or health concerns which required regular visits to a health professional (Fig 1).

It must be noted that we refer to mother’s and father’s self-reported GGH and illness as parental global health and parental illness (or maternal and paternal) for ease of reading. Similarly, we refer to parent-reported child global health and illness as child global health and child illness.

Data Analysis

Pearson’s2tests were used to describe child-parent

health-related associations in the 2⫻2 tables formed by tabulating child global health and child illness versus parental global health and parental illness. To further explore the odds ratios implicit in these associations, logistic regression was used to obtain odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals that were adjusted for child age, sex, reporting parent’s level of education and reporting parent’s coun-try of birth. Child global health and child illness were dependent variables in these models. Weights based on selection probabilities in the 2-stage sampling procedure were used in the logistic re-gression models to give conclusions that apply to the population of school children in Victoria.

We examined the effect of parent characteristics on their reports of child health using the multidimensional domains within the CHQ to determine whether parental global health and illness were more strongly associated with particular domains of child func-tional health and well-being, ie, social roles, physical health, or emotional health related domains. The 20th percentile of observed responses for the multi-item CHQ scales was used to differentiate children whose health was significantly worse (those with re-sponses below the 20th percentile value) from children whose health was better. These thresholds were determined separately for mother and father reporters as the analysis was stratified by the reporting parent’s gender. This choice of the 20th percentile corresponds closely to the parametric concept of one standard deviation below the mean, shown previously to indicate socially and clinically meaningful differences in the health status of chil-dren at a population level36 and within clinical studies.38

Al-though mean scale scores are often used in analyses of the CHQ,36,42we used this approach because 1) the scale scores are

pro-nounced ceiling effects on the upper ends of the Role/Social and Physical Functioning scales). The statistical packages SPSS43and

STATA44were used for the analyses.

For each CHQ scale, the proportion of children rated above the 20th percentile by parents with reported illness was compared using an odds ratio and confidence interval (from logistic regres-sion models that weighted for sampling and adjusted for possible confounders) with the proportion of children rated above the 20th percentile by parents who did not report any illness (separately for mothers and fathers). These analyses were repeated for parental global health.

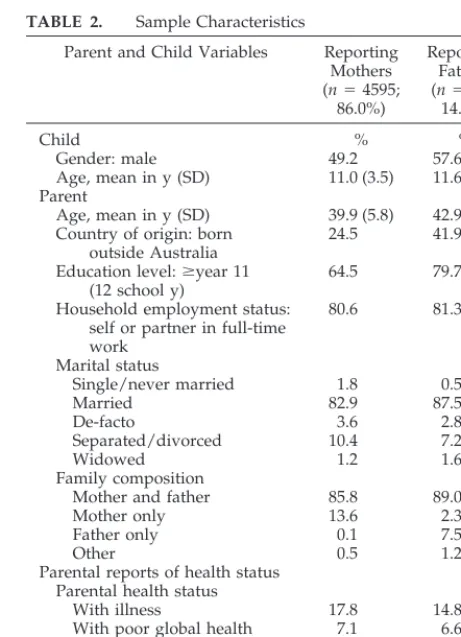

RESULTS Sample

Five thousand four hundred fourteen question-naires were returned (72% response rate). Of these, 5340 (99%) were completed by a parent (biological, step, adoptive, or foster) whose gender was recorded (mothers 86%, fathers 14%, Table 2). All items were answered by at least 94% of the parent respondents, except “child illness” (response rate 86% for mothers, 90% for fathers). Lower responses on this item may

be because of response burden as the layout of the question required respondents to check “no” to all illnesses to be categorized as having no illness.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics by Parent Gender

Similar health characteristics were found for mother and father reporters and for their children. Of 4595 mothers, 7.1% reported poor parental global health and 17.8% reported one or more health con-cerns or illnesses. Of 745 fathers, 6.6% reported poor parental global health and 14.8% reported parental illness (Table 2). Overall, only 1.7% of children were reported to have poor global health, but⬃50% were reported to have an illness.

There were no differences between mother and father reporters on marital status, combined parental (household) employment status, and child living ar-rangements (Table 1). However, higher proportions of fathers had been educated for longer than 11 years of school and were born outside Australia. Child age,

gender, parental education, and country of birth were subsequently adjusted for as possible con-founders in the multivariate analyses.

Association of Child Health With Parent Health According to Parent Gender

Tables 3A and 3B show child global health and illness, stratified by parent reports of their own global health and illness. A higher proportion of mothers who reported poor parental global health reported poor child global health than mothers who reported good parental global health. All fathers with poor parental global health reported good child global health. Only a small proportion of fathers with good parental global health reported poor child global health (1.3%, Table 3A). Similarly for child illness, mothers with poor global health reported higher proportions of child illness than mothers with good global health. However, there were no child illness differences between fathers with good or poor parental global health. Similar patterns were found for mothers and fathers with or without illness (Ta-bles 3A and 3B).

Multivariable Logistic Regression

The conclusions from the exploratory analysis above were confirmed when adjustment was made for the possible confounders of child age, child gen-der, parental education and parental country of birth (Table 4). As none of the 47 fathers with poor paren-tal global health reported poor child global health, an

TABLE 1. CHQ Scales and Their Interpretation

Scale Abbreviation Interpretation

Physical functioning PF Limitation to physical activity

because of health problems. Role/social

limitations-emotional/behavioral

REB Limited in ability to perform school

work or activities with friends as a result of emotional or behavioral problems.

Role/social limitations-physical

RP Limitation in ability to perform

school work or activities with friends as a result of physical health problems.

Bodily pain BP Presence and extent of pain or

limitations because of pain.

Behavior BE Frequency of behavioral problems

and ability to get along with others.

Mental health MH Frequency of negative and positive

states of well-being.

Self-esteem SE Degree of satisfaction with abilities,

looks, family/peer relationships, and life in general.

General health GH Belief about child’s past, current,

and future health. Parental

impact-emotional

PE Degree of parental concern/worry

because of child’s health.

Parental impact-time PT Limitations in personal time because

of child’s health.

Family activities FA Limitations in or interruptions to

family activities because of child’s health.

Family cohesion FC How well the family gets along with

one another.

Change in health CH Change in health over the previous

year.

TABLE 2. Sample Characteristics

Parent and Child Variables Reporting Mothers (n⫽4595;

86.0%)

Reporting Fathers (n⫽745;

14.0%)

Child % %

Gender: male 49.2 57.6

Age, mean in y (SD) 11.0 (3.5) 11.6 (3.4)

Parent

Age, mean in y (SD) 39.9 (5.8) 42.9 (6.3)

Country of origin: born outside Australia

24.5 41.9

Education level:ⱖyear 11 (12 school y)

64.5 79.7

Household employment status: self or partner in full-time work

80.6 81.3

Marital status

Single/never married 1.8 0.5

Married 82.9 87.5

De-facto 3.6 2.8

Separated/divorced 10.4 7.2

Widowed 1.2 1.6

Family composition

Mother and father 85.8 89.0

Mother only 13.6 2.3

Father only 0.1 7.5

Other 0.5 1.2

Parental reports of health status Parental health status

With illness 17.8 14.8

With poor global health 7.1 6.6

Child health status

With illness 53.5 51.6

With poor global health 1.8 1.2

estimate of association for paternal global health and child global health could not be obtained. However, as the odds ratio for data from all parent reports was less than that for mothers alone, it was concluded that father reported cases could not have had a strong association between reporter health and child health reports.

Multiple Dimensions of Child Health and Well-Being—Analysis of CHQ Scales

The associations between poor parental global health or illness and poorer child health and well-being (ie, below the 20th percentile on each scale of the CHQ) are shown in Table 5. There was an in-creased likelihood of a child being rated “unwell” on all scales of the CHQ if their mother reported poor parental global health or illness. For Mental Health there were strong associations observed for mothers that contrasted with weak associations observed for fathers (for parental global health and parental ill-ness).

DISCUSSION

There was a strong association between mothers’ reports of their own global health and their reports of their children’s health that was not seen for fathers, even after adjustment for confounding of child and parent characteristics. The reporting of perceived poor global health by mothers as opposed to illness was more strongly associated with reporting poor child health scores on all domains of functioning, social role, physical and emotional health as mea-sured by the CHQ. The strongest association was found between poor maternal global health and chil-dren’s Mental Health, an item that had one of the weakest associations with paternal global health.

The strengths of our study were that it was large and allowed us to draw conclusions for a general population of children aged 5 to 18 years. The use of a comprehensive measure of child health and

well-being enabled the analysis of child health from a more contemporary perspective45 than merely the absence of illness or disease. Information collected on the health of the reporting parent allowed us to examine the influence of the reporting parents’ per-ception of their own health which is rarely consid-ered when reports of child health are obtained.

As the study was cross-sectional, we were unable to assess whether there was a causal relationship between parental and child health and illness. Two specific factors may make selection bias a real possi-bility in explaining some of these results: only small numbers of fathers responded and each family was free to select which parent responded, and in a ques-tionnaire-based survey such as this, it is not possible to know whether mothers and fathers were more or less likely to respond based on their own experience with illness. Also, we obtained only 1 response from each family, preventing comparisons of reports from both parents on the one child. Despite this, the gen-der differences are striking and deserve further re-search.

Finally, bias in the child illness results was also possible because of a response rate that was lower than for other measures, and parents who did not answer this question were more likely to have poor global heath and illness than those who did. Our suspicion is that children for whom this was missing were more likely to be well with reported fatigue accounting for the noncompletion of what may have been a series of no responses. If we were correct in this assumption, this would have reduced the total proportion of ill parents with well children in the sample, which would have heightened the strength of associations observed.

This study lends further support to the hypothesis that there are factors other than illness alone which influence the parent’s perception of their own health, and consequently, the way in which they report their child’s health. These findings are consistent with the one previous study to have addressed the health of parents on the impact of their perception of child health, which concluded that the health and well-being of the parent is a critical factor in the parent’s perception of how well the child is doing.33 Simi-larly, the nature of parental involvement or commu-nication with the child is likely to affect differences in parental perspectives. A wealth of research has ad-vanced concepts of maternal depression on bonding and attachment, although much less is known about fathers.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Child Health Surveillance

Our findings have several implications for those involved in the health care of children and adoles-cents. First, it strengthens the acknowledged rela-tionship between maternal and child health that drives most generic health services for children. Sec-ond, much of the information about child health and well-being that clinicians, educators, and researchers rely on comes from parents, especially mothers. It is vital that the relationship between what is reported by parents and potential confounders or biases be

TABLE 3A. Child Global Health and Illness by Parent Global Health

Parent Global Health

Child Global Health % (n)

Child Illness % (n)

Good Poor No Illness Illness

Mother reporter

Good 98.8 (4176) 1.2 (51) 48.0 (1778) 52.0 (1927) Poor 90.8 (296) 9.2 (30) 25.4 (64) 74.6 (188) Father reporter

Good 98.7 (673) 1.3 (9) 48.2 (300) 51.8 (323)

Poor 100.0 (47) 0 (0) 53.5 (23) 46.5 (20)

TABLE 3B. Child Global Health and Illness by Parent Illness

Parent Global Health

Child Global Health % (n)

Child Illness % (n)

Good Poor No Illness Illness

Mother reporter

No illness 98.7 (3683) 1.3 (47) 49.9 (1650) 50.1 (1655) Illness 95.8 (771) 4.2 (34) 29.0 (186) 71.0 (456) Father reporter

explored and not taken for granted. Our report is of importance because it relates not only to the veracity of information obtained in clinical care, but also to that obtained and potentially used in quality assur-ance and public health activities. The way forward in certain areas of clinical care is to consider the use of standardized measures of health and well-being, such as the CHQ, and to do so we need confidence that we have identified what the reports actually mean. Third, the results support previous findings from other studies that demonstrate relationships between parental health and child health.1–32 Specif-ically, the significant association between mothers reporting their own illness or poor global health and their reports of poorer child health and illness sup-ports recent research,15stressing the importance that clinicians address the health problems of the mother when they are attending to concerns related to the child. Also, health professionals in contact with mothers with health concerns should be aware of the

increased likelihood that their children may require additional health care attention if reported health is indicative of actual health. The reciprocal benefit of addressing the needs of mothers at the same time that their children are being attended to, in new models of pediatric care,46 would seem to be high-lighted by the findings of our study. In future studies of child health and quality of life using proxy re-ports, these findings need to be examined in more detail and results replicated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Public Health and Development Branch (Department of Human Services, Victo-ria) and the Victorian Public Health Training Scheme.

We also thank Professor Frank Oberklaid, Kylie Hesketh, and Diana Trinchera.

REFERENCES

1. MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Prevention of neural tube defects. Results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study.Lancet. 1991; 338(8760):131–137

2. Dennison E, Fall C, Cooper C, Barker D. Prenatal factors influencing long-term outcome.Horm Res.1997;48(suppl 1):25–29

3. Eskenazi B, Prehn AW, Christianson RE. Passive and active maternal smoking as measured by serum cotinine: the effect on birth weight.Am J Public Health.1995;85:395–398

4. Martin SL, Gordon TE, Kupersmidt J B. Survey of exposure to violence among the children of migrant and seasonal farm workers.Public Health Rep.1995;110:268 –276

5. Dezateux C, Stocks J, Dundas I, Fletcher M E Impaired airway function and wheezing in infancy: the influence of maternal smoking and a genetic predisposition to asthma.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.1999;159: 403– 410

6. Grunseit F. Aboriginal children.Med J Aust.1984;140:697– 698 7. Jolly, Nolan T, Moller J, Vimpani G. The impact of poverty and

disad-vantage on child health.J Paediatr Child Health.1991;27:203–217 8. Starfield. Child health care and social factors: poverty, class, race.Bull N

Y Acad Med.1989;65:299 –306

9. Wilkinson R, Marmot M.Social Determinants of Health. The Solid Facts.

Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization; 1998

10. Oates RK, Tebbutt J, Swanston H, Lynch DL, O’Toole B. Prior childhood sexual abuse in mothers of sexually abused children.Child Abuse Negl.

1998;22:1113–1118

11. Sallis JF, Patterson TL, McKenzie TL, Nader PR. Family variables and physical activity in preschool children.J Dev Behav Pediatr.1988;9:57– 61 12. Klesges RC, Coates TJ, Brown G, et al. Parental influences on children’s eating behavior and relative weight.J Appl Behav Anal.1983;16:371–378 13. Hall D.Health for All Children. 3rd ed. British Paediatric Association,

Oxford University Press; 1996

14. McCormick M, Brooks Gunn J, Shorter T, Holmes JH, Heagarty MC. Factors associated with maternal rating of infant health in Central Harlem.Dev Behav Pediatr.1989;10:139 –143

15. Kahn RS, Wise PH, Finkelstein JA, Bernstein HH, Lowe JA, Homer CJ. The scope of unmet maternal health needs in pediatric settings. Pediat-rics.1999;103:576 –581

16. Silburn SR, Zubrick SR, Garton A, et al.Western Australia Child Health Survey. Perth, Western Australia: Family and Community Health,

Aus-TABLE 4. Adjusted ORs for Parent-Child Health-Related Associations

Outcome Parent Health Adjusted OR‡ (95% CIs)

All Parents Mothers Fathers

Child global health Parent global health 7.5* (4.7–12.0) 9.0* (5.5–14.6) § Child illness Parent global health 2.0* (1.6–2.7) 2.5* (1.9–3.4) 0.8 (0.4–1.5) Child global health Parent illness 3.4* (2.2–5.3) 3.8* (2.4–6.0) 0.7 (0.1–6.0)

Child illness Parent illness 2.1* (1.8–2.5) 2.4* (2.0–2.9) 1.0 (0.7–1.6)

*Pvalue⬍.05.

‡ ORs and 95% CIs adjusted for child age, child gender, parental education and parental country of birth.

§ Insufficient numbers with which to estimate association.

TABLE 5. Association of Parent Global Health and Child Health Below CHQ 20th Percentile

Adjusted OR (95% CIs)‡ of Child CHG score⬍20th Percentile

Parent Illness Versus No Illness

Poor Versus Good Parent Global Health

Mothers Fathers Mothers Fathers

PF 1.9* 1.8* 2.7* 1.7

(1.5–2.3) (1.1–3.0) (2.0–3.5) (0.9–3.3)

REB 1.7* 1.7 2.6* 1.8

(1.4–2.1) (1.0–2.8) (2.0–3.4) (0.9–3.7)

BE 1.7* 0.9 2.6* 2.2*

(1.4–2.1) (0.6–1.4) (2.0–3.4) (1.2–4.0)

MH 2.6* 1.0 3.6* 1.3

(2.1–3.2) (0.6–1.9) (2.8–4.7) (0.6–2.9)

SE 1.7* 0.8 3.2* 1.4

(1.4–2.1) (0.5–1.4) (2.4–4.2) (0.7–2.7)

PE 2.0* 2.0* 3.5* 1.9*

(1.7–2.5) (1.2–3.2) (2.7–4.6) (1.0–3.7)

RP 1.4* 1.6 2.1* 1.6

(1.1–1.8) (0.9–2.6) (1.6–2.9) (0.8–3.3)

BP 1.8* 1.8* 2.4* 2.3*

(1.5–2.2) (1.1–3.0) (1.9–3.2) (1.1–4.5)

GH 2.1* 1.7* 3.2* 1.6

(1.8–2.6) (1.1–2.8) (2.5–4.1) (0.8–3.1)

PT 1.9* 1.6 3.0* 1.2

(1.6–2.3) (1.0–2.6) (2.3–4.0) (0.6–2.3)

FA 1.8* 1.9* 3.1* 1.7

(1.5–2.1) (1.2–3.1) (2.4–4.0) (0.9–3.2)

*Pvalue⬍.05.

tralian Bureau of Statistics and the TVW Telethon Institute for Child Health Research; 1996 (ISBN No. 0 642 20759 3)

17. Pulsifer MB, Hoon AH, Gopalan R, Capute AJ. Maternal estimates of developmental age in preschool children.J Pediatr. 1994;125(suppl): S18 –S24

18. Glascoe FP, Sandler H. Value of parents’ estimates of children’s devel-opmental ages.J Pediatr.1995;127:831– 835

19. Glascoe FP, Dworkin PH. The role of parents in the detection of devel-opmental and behavioral problems.Pediatrics.1995;95:829 – 836 20. Glascoe FP, MacLean WE, Stone WL. The importance of parents’

con-cerns about their child’s behavior.Clin Pediatr.1991;30:8 –11 21. Koniak Griffin D, Verzemnieks I. The relationship between parental

ratings of child behaviors, interaction, and the home environment.

Maternal-Child Nurs J.1995;23:44 –56

22. Mack P, Trew K. Are fathers’ views important?Health Visitor.1991;64: 257–258

23. Baker BL, Heller TL. Preschool children with externalizing behaviors: experience of fathers and mothers. J Abnorm Child Psychol.1996;24: 513–532

24. Eiser C, Havermans T, Pancer M, Eiser JR. Adjustment to chronic disease in relation to age and gender: mothers’ and fathers’ reports of their children’s behavior.J Pediatr Psychol.1992;17:261–275

25. Hoekstra Weebers JE, Jaspers JP, Kamps WA, Klip EC. Gender differ-ences in psychological adaptation and coping in parents of pediatric cancer patients.Psychol Oncol.1998;7:26 –36

26. Dyson LL. Fathers and mothers of school-age children with develop-mental disabilities: parental stress, family functioning, and social sup-port.Am J Ment Retard.1997;102:267–279

27. Heaman DJ. Perceived stressors and coping strategies of parents who have children with developmental disabilities: a comparison of mothers with fathers.J Pediatr Nurs.1995;10:311–320

28. Holmbeck GN, Gorey Ferguson L, et al. Maternal, paternal and marital functioning in families of preadolescents with spina bifida.J Pediatr Psychol.1997;22:167–181

29. Thelin T, McNeil TF, Aspegren Jansson E, Sveger T. Identifying children at high somatic risk: possible long-term effects on the parents’ views of their own health and current life situation.Acta Psychiatr Scand.1985; 71:644 – 653

30. Wishart MC, Bidder RT, Gray OP. Parents’ report of family life with a developmentally delayed child.Child Care Health Dev.1981;7:267–279 31. Davis DJ, Schultz CL. Grief, parenting and schizophrenia.Soc Sci Med.

1998;46:369 –379

32. Saddler AL, Hillman SB, Benjamins D. The influence of disabling con-dition visibility on family functioning.J Pediatr Psychol.1993;18:425– 439 33. Daltroy LH, Liang MH, Fossell AH, Goldberg MJ, and the Pediatric Outcomes Instrument Development Group. The POSNA Pediatric Mus-culoskeletal Functional Health Questionnaire. Report on reliability, va-lidity, and sensitivity to change.J Pediatr Orthop.1998;18,5:561–571 34. Waters E, Salmon L, Wake M. The parent-form Child Health

Question-naire in Australia: comparison of reliability, validity, structure and norms.J Pediatr Psychol.1999. In press

35. Ware JE Jr, Nelson EC, Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. Preliminary tests of a 6-item general health survey: A patient application. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE, eds.Measuring Functioning and Well-Being: The Medical Out-comes Study Approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992: 291–308

36. Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE.Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ): A Users Manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1996

37. Waters E, Wright M, Wake M, Landgraf J, Salmon L. Measuring the health and well-being of children and adolescents: a preliminary com-parative evaluation of the child health questionnaire in Australia. Am-bulatory Child Health.1999;5:131–141

38. Kurtin PS, Landgraf JM, Abetz L. Patient based health status measure-ments in pediatric dialysis: expanding the assessment of outcome.Am J Kidney Dis.1994;24:376 –382

39. Stein RE, Jessop DJ. Functional Status II: a measure of child health status.Med Care.1990;28:1041–1055

40. Newacheck PW, Halfon N. Prevalence and impact of disabling chronic conditions in childhood.Am J Public Health.1998;88:610 – 617 41. McCormick MC, Brooks Gunn J, Workman Daniels K, Peckham G.

Maternal rating of child health at school age: does the vulnerable child syndrome persist?Pediatrics.1993;92:380 –388

42. Landgraf JM, Maunsell E, Speechley KN, et al. Canadian-French, Ger-man and UK versions of the Child Health Questionnaire: methodology and preliminary item scaling results.Qual Life Res.1998;7:433– 445 43.SPSS for Windows: Release 6.1.3.Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 1995

44. StataCorp.Stata Statistical Software: Release 5.0.College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 1997

45. World Health Organization. The Constitution of the World Health Organization: WHO Chronicles,1, 29.Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1947 46. Zuckerman B, Parker S. Preventive pediatrics—new models of

DOI: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1422

2000;106;1422

Pediatrics

Salmon

Elizabeth Waters, Jodie Doyle, Rory Wolfe, Martin Wright, Melissa Wake and Louisa

Parent-Reported Child Health

Influence of Parental Gender and Self-Reported Health and Illness on

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/6/1422

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/6/1422#BIBL

This article cites 36 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/community_pediatrics

Community Pediatrics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1422

2000;106;1422

Pediatrics

Salmon

Elizabeth Waters, Jodie Doyle, Rory Wolfe, Martin Wright, Melissa Wake and Louisa

Parent-Reported Child Health

Influence of Parental Gender and Self-Reported Health and Illness on

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/6/1422

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.