grosvenor management consulting

a level 7 15 london circuit canberra act 2601 t (02) 6274 9200 abn 47 105 237 590 e grosvenor@grosvenor.com.au

w grosvenor.com.au

National Solar Schools Program

Evaluation Report

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 2

Table of contents

Table of figures

... 5

Table of tables

... 7

List of abbreviations ... 8

1

Executive Summary... 9

1.1

Introduction ... 9

1.2

Input and design ... 11

1.3

Process and implementation ... 12

1.4

Achievements against the NSSP objectives (impacts and outcomes)

13

1.5

Value for money ... 17

1.6

Sustainability ... 18

1.7

Implications for the future ... 19

1.8

Recommendations ... 20

2

Introduction ... 21

2.1

Background ... 21

2.2

Scope and objectives ... 22

2.3

The National Solar Schools Program ... 23

3

Approach and method ... 29

3.1

Evaluation resources ... 29

3.2

Evaluation limitations ... 30

4

Structure of the evaluation report ... 32

PART A – Input & Design

... 33

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 3

5.1

Conclusions - funding approach ... 38

PART B – Process & Implementation

... 39

6

NSSP implementation ... 39

6.1

Roles and responsibilities of the NPA ... 45

6.2

Conclusions – NSSP implementation ... 46

7

Performance against milestones ... 47

7.1

Performance milestones ... 47

7.2

Performance against each milestone ... 48

7.3

Delays and challenges in completing projects ... 50

7.4

Conclusions – performance against milestones ... 52

PART C – Impacts & Outcomes

... 53

8

Achievement of NSSP objectives ... 53

8.1

Energy efficiency & renewable energy ... 53

8.2

Rainwater ... 78

8.2.1

Conclusions - rainwater ... 84

8.3

Educational Benefits ... 85

8.3.1

Conclusions – educational benefits ... 96

8.4

Supporting industry growth ... 98

9

Value for money ... 105

9.1

Conclusions – value for money ... 109

10

Sustainability of NSSP ... 110

10.1

Achieving behavioural change ... 110

10.2

Maintenance of PV systems ... 115

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 4

11

Implications for the future ... 120

12

Recommendations ... 122

Attachment A: NSSP Review Terms of Reference ... 123

Attachment B: Activities undertaken by DRET following the interim evaluation

... 124

Attachment C: Further information ... 127

Attachment D: National Partnership Agreement ... 129

Attachment E: Evaluation design and methodology ... 139

Attachment F: Related programs implemented by the States and Territories . 141

13

References ... 144

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 5

Table of figures

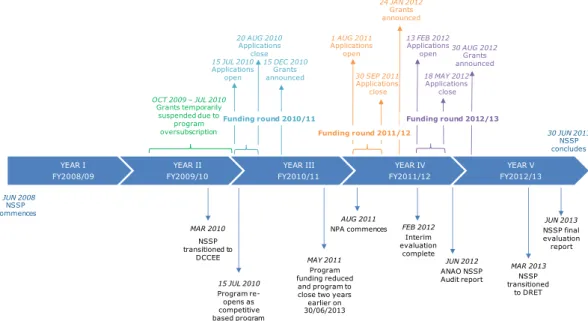

Figure 1: NSSP timeline ... 24Figure 2: Number of survey responses ... 30

Figure 3: Project completion time for non-government schools ... 44

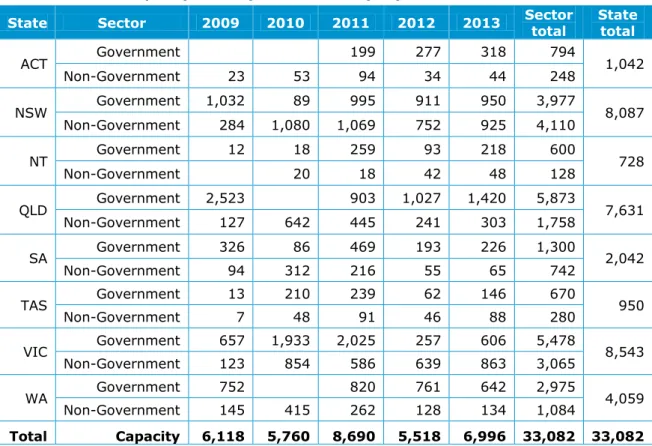

Figure 4: Systems installed by state and sector ... 54

Figure 5: Geographical distribution of installed PV systems ... 55

Figure 6: PV electricity generated by QLD schools in FY2010 ... 59

Figure 7: Performance of NSW PV systems versus CER Zone 3 estimates ... 60

Figure 8: Size of systems installed ... 65

Figure 9: Cost per Watt of NSSP systems installed by year ... 66

Figure 10: Average kW of PV installation by state/territory for government schools and non-government sector ... 67

Figure 11: Range in cost of systems... 68

Figure 12: Cost of abatement as compared to benchmarks ... 71

Figure 13: Total and imported energy consumption – median per NSSP QLD school ... 75

Figure 14: Students enrolled and floor area ... 75

Figure 15: Median energy intensity of QLD schools ... 76

Figure 16: Percentage of NSSP schools installing rain water tanks ... 79

Figure 17: Average rainfall, tank capacity, roof area and harvesting potential per school ... 81

Figure 18: Purposes for which rainwater tanks were connected ... 83

Figure 19: Collaborations and associated behavioural change ... 89

Figure 20: Schools incorporating DCSVS data into lessons plans (by funding year) ... 92

Figure 21: NSSP installed PV capacity as a proportion of total market installed capacity ... 98

Figure 22: Commonwealth, state/territory and non-government financial contributions ... 102

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 6

Figure 23: Pathway from NSSP inputs to outcomes ... 110

Figure 24: Behavioural change as a result of the NSSP ... 111

Figure 25: Implementation of maintenance plan (by sector) ... 117

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 7

Table of tables

Table 1: Implementation approach by states and territories ... 39Table 2: Energy generation systems installed ... 53

Table 3: Types of energy generation systems installed ... 55

Table 4: Capacity of PV systems installed (kW) ... 56

Table 5: Electricity displaced (MWh) by year ... 56

Table 6: Theoretical annual electricity generation from PV systems installed (MWh) ... 57

Table 7: Performance of systems in SA and WA ... 61

Table 8: May 2012 Audit findings of DCSVS operation. ... 62

Table 9: Industry standard price (AU$/W) for solar panels ... 69

Table 10: Australian trends in typical system prices for grid applications up to 5 kWp compared to NSSP PV system prices paid (AU$ ex GST) ... 69

Table 11: NSSP schools installing energy efficiency items ... 72

Table 12: Number of schools installing energy efficiency items by type ... 73

Table 13: Energy efficient lighting expenditure and quantity installed ... 73

Table 14: Rainwater tank installations by state, sector and year ... 78

Table 15: Average rainfall, installed tank capacity, roof area and harvesting potential by state and sector ... 80

Table 16: Cost per litre of tanks installed ... 84

Table 17: Key findings of the interim evaluations of the NSSP ... 85

Table 18: NSSP installers as a proportion of industry providers ... 99

Table 19: Key findings of the interim evaluations of the NSSP ... 103

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 8

List of abbreviations

ABS – Australian Bureau of Statistics ACT – Australian Capital Territory

AuSSI – Australian Sustainable Schools Initiative Black data – Net energy consumed from the grid CEC – Clean Energy Council

CER – Clean Energy Regulator

COAG - Council of Australian Governments

DCCEE – Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency DCSVS – Data Collection Storage and Visualisation System

DEEWR – Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations DRET – Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism

Green data – Renewable energy generated

IPART – Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal of New South Wales kW / MW– Kilowatt / Megawatt, a unit of power

kWh / MWh – Kilowatt hour / Megawatt hour, a unit of energy

KWp / MWp- the peak (nameplate) output power in kilowatts / megawatts NAPLAN – National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy

NPA – National Partnership Agreement NSSP – National Solar Schools Program NSW – New South Wales

NT – Northern Territory

PM&C – Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet PV – Photovoltaic

QLD – Queensland SA – South Australia

SEWPaC – Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities

SHW – Solar Hot Water

STC – Small-scale Technology Certificate TAS – Tasmania

VIC – Victoria

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 9

1

Executive Summary

1.1

Introduction

This report documents the final evaluation of the National Solar Schools Program (NSSP).

The NSSP is part of the Australian Government’s 2007 ‘Solar Schools – Solar Homes’ election commitment. The NSSP commenced on 1 July 2008, and closed on 30 June 2013. The NSSP offered eligible primary and secondary schools the opportunity to compete for grants of up to $50,000, to install solar and other renewable systems, rainwater tanks and a range of energy efficiency measures.

The stated objectives of the NSSP were to:

Key statistics for the program include:

$217 million Commonwealth funding 2008/09 – 2012/13

8,300 schools registered (88% of all Australian schools)

5,300 schools awarded a grant (56% of all Australian schools)

4,897 photo voltaic (PV) systems funded (92% of NSSP projects)

279 other renewable energy systems funded

33,082 kW of PV system capacity funded equivalent to 2.4% of school consumption and meeting needs of 6,075 homes

$196.52 per tonne of Carbon emissions offset for PV systems

1,559 separately funded energy efficiency projects

61,063 litres rain water tank capacity funded

2,640 ML of theoretical rain water harvesting potential allow schools to:

- generate their own electricity from renewable

sources

- improve their energy efficiency and reduce their

energy consumption

- adapt to climate change by making use of rainwater

collected from school roofs

- provide educational benefits for school students and their communities

support the growth of the renewable energy industry.

N S

S

P

O

B

J E

C

T

I V

E

S

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 10 This report evaluated the NSSP against the program design, the

management of the program, and importantly, the outcomes achieved against the stated objectives as represented in the following diagram.

•To what extent have NSSP objectives been achieved, including allowing schools to:

- Improve energy efficiency and reduce energy consumption

- Generate own electricity from renewable sources - Adapt to climate change

by making use of rainwater collected from school roofs

- Provide education benefits for school students and their communities

- Support the growth of the renewable energy industry?

•Is there still a need or priority for Commonwealth and State Government activity and/or

collaboration in this policy area?

Impacts & Outcomes

•How appropriate was the NPA funding mechanisms (performance milestones and associated payments) for achieving the objectives?

•How appropriate was the maximum amount of funding for each school? •How appropriate was the

annual funding allocations for each state and territory, introduced in July 2010?

•How appropriate were the eligible items that schools could install?

Input & Design

•How effective was the program implementation in respect to its stated objectives? •What were the key

challenges and successes in the implementation of the NSSP?

•To what extent have DCCEE and the States fulfilled their roles and responsibilities under the NPA?

•Are approved project items in proportion to the funding obtained?

•Has value for money in delivering the objectives been achieved? •Have project milestones

been achieved and if not, why?

Process & Implementation

The evaluation considered information sourced from:

stakeholder interviews including state and territory government agencies responsible for the implementation of the Program within government schools

a survey of NSSP funded schools data collected by NSSP

selected case studies1

1 Conducted by staff within DRET.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 11

1.2

Input and design

The Program was initially established within the (former) Commonwealth Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, transferred to the (former) Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE), and then transferred to the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (DRET) since the winding up of DCCEE in 20132.

The program was initially a demand based program which faced over-subscription in 20093. While the move to a competitive, merit-based selection arrangement was a positive and effective development, the Program may have benefitted from such a model being in place from the outset in the event demand exceeded available funding.

The funding model for government schools with states and territories under the National Partnership Agreement (NPA) was consistent with the typical approach of other programs funded by the Commonwealth and implemented by the states and territories under the Federal Financial Relations Act. The funding model for non-government schools was a grant model and may have benefited from a payment model where part of the payment was

withheld until successful completion as is recommended in the ANAO’s Better Practice Guide to Administration of Grants.

The amount of the grant for each school4 was generally seen as adequate by most stakeholders. The amount enabled schools to install adequate sized systems, with system sizes increasing as costs of PV systems reduced across the period of the NSSP. With the exception of ACT and QLD government schools, very little additional funding was invested by the school or state/territory to top up project funds.

Concerns were raised by many states/territories about the lack of funding for administrative and ongoing maintenance costs; however, it is reasonable to expect that the states/territories make some contribution, particularly given most would have benefited from reduced energy and water costs.

2 The term DRET is used throughout this report to refer to the Department administering the NSSP.

3 NSSP applications exceeded available funding. The program had to be temporarily suspended to enable changes to be put in place, including the merit based competitive process and additional arrangements with the states and territories.

4 $50,000 although some states and territories elected to reduce the funding per school during the Program so that more schools could be funded.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 12

1.3

Process and implementation

The NSSP was implemented within the context of many existing and prior state and territory policies and programs. The states and territories also took very different approaches to implementing NSSP. The flexibility afforded under the NSSP was appropriate to accommodate the differences between states and territories, including ensuring alignment with their existing program and education models.

However, the differences created some challenges, notably in achieving consistency in data capture, timing to implement projects, and consistency in implementation within the curriculum of government schools.

The flexibility also afforded to schools to apply for a range of eligible items allowed for schools to address their varying needs. However, initial

consultation with the states and territories about the type of eligible energy efficiency items would have further assisted in meeting the local design requirements and climatic conditions.

The NSSP led to the development of a range of practical resources

(factsheets/case studies). Some schools and stakeholders raised issues with the program guidelines and supporting material. However, 80% of schools who responded to the survey indicated program guidelines and supporting material were useful and easy to understand. The website was particularly mentioned as a valuable source of information. Similar programs should seek to make these resources available as early as possible, ideally from the onset of the program.

All states and territories met milestones I – III under the NPA. There were a range of factors that led to delays in finalising projects, primarily relating to delays in agreeing the NPA, installation issues for PV systems including ensuring a fully operational DCSVS5 (refer further detail in 1.4 below). This also meant that many states and territories struggled to meet the planned due dates for milestone IV under the NPA6.

While some issues were raised with regard to the clarity in roles and

responsibilities between DRET and the states and territories under the NPA, generally it was found that the roles and responsibilities were appropriate and clear. Improvements were made to various guidance material during the NSSP to improve the understanding of the roles and expectations of

states/territories and schools.

5 The DCSVS is the technical term used by the NSSP to describe the data monitoring system, which displays green data (electricity generated from the solar PV system) and black data (electricity consumed by the school).

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 13

1.4

Achievements against the NSSP objectives (impacts and

outcomes)

There have been significant achievements against the NSSP objectives. The evaluation has also identified some lessons learned that might inform future policy considerations and actions by the Australian Government and states and territories. These are summarised below.

Achievements

Lessons learned

Generate electricity from renewable sources, improve energy efficiency and reduce energy consumption

4,897 PV systems funded (91% of NSSP schools and 94.5% of renewable energy systems funded)

279 other renewable energy systems funded

33,082 kW of PV capacity funded

44,354 MWh theoretical electricity generated per annum by PV systems

1,250 MWh electricity displaced by solar hot water and heat pumps

PV meeting 2.4% of school needs

PV electricity equivalent to meeting needs of 6,075 homes

PV electricity estimated at 1.62% of total Australian PV generation

Performance of PV systems largely in line with CER deemed estimates

Costs of PV systems in line with industry benchmarks, with small premium appearing to reflect purchase of higher quality components

Cost of abatement for PV systems well below equivalent solar

programs

1,559 energy efficient projects

Estimated 225,640 lights replaced

Not all PV systems operating at expected performance7

Many DCSVS systems are not reporting both green (PV electricity generated) and black (electricity consumed) data, which could impact educational and behavioural change outcomes. Action is progressively being taken to address DCSVS reporting issues8.Changes were made to guidance material to

incentivise completion including fully operational DCSVS

Many non-government schools and some states and territories

capitalised on significant reduction in PV system prices to install larger capacity systems than was approved in their NSSP application

7 25 systems were referred to state and territories for investigation.

8 The DCSVS sample data indicates that approximately 20% of schools do not have a fully operational DCSVS.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 14

Achievements

Lessons learned

with energy efficient lights, estimated at reducing electricity consumption by an estimated 10,541 MWh, accounting for 0.9% of school consumption for those schools

While floor space of schools increased across NSSP, energy efficiency improved measured in reductions in median energy intensity

Adapt to climate change by making use of rainwater collected from school roofs

5,310 rain water tanks funded

424,932 litres of capacity

2,640 ML of rain harvesting potential

Evidence suggests that more than half of installations are using rain water collected for purposes other than small scale irrigation

Some states and territories maximised water harvesting potential by maximising tank

capacity and area of roof connected to tanks

Greater use of water for purposes other than small-scale irrigation reduces water loss

Greater focus could have been placed on water efficiency by including water saving measures such as dual flush toilets as an eligible item and providing educational resources on water saving initiatives

Some states and territories took the opportunity to include water, in addition to energy, when

implementing the DCSVS product in their schools (ACT, NSW). Including the requirement for the DCSVS to monitor water consumption, in addition to energy, may have contributed to reductions in water consumption

Provide educational benefits for school students and their communities

Program integrated into other state/territory and federal (e.g.

Challenges in achieving consistent and widespread adoption of

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 15

Achievements

Lessons learned

AuSSI) environmental education initiatives, enhancing educational benefits

Many schools implementing

renewable energy/energy efficiency into lessons plans, leveraging DCSVS and practical hands on learning. Many believed this was the most important benefit of the NSSP

Many educational materials developed by states/territories, DRET and industry

Instances where educational materials leveraged the resources, knowledge and experience of PV suppliers

Significant amount of promotion occurred within communities around the ‘launch’ of NSSP school projects

Evidence that the NSSP led to change in behaviour amongst students and staff

sustainability in lesson plans of schools9

Need to ensure personnel responsible for NSSP at a

state/territory level collaborate with those responsible for curriculum development

Monitoring, collection and utilisation of DCSVS data was key in driving as well as measuring the effects of behavioural change and facilitating the educational activities

Uptake at a school level is heavily dependent on:

- maintaining momentum when delays in installation are being experienced

- quality of educational materials provided and staff resources to embed in lesson plans

- turnover in staff responsible for NSSP and knowledge transfer - competing priorities overtake NSSP - ensuring DCSVS is fully operational

and utilised

- technical understanding of teachers/staff responsible for NSSP, ensuring support and training is provided

Support the growth of the renewable energy industry`

>$255 million including NSSP funds and co-contributions

Represented between 0.56% and 7.44% of installed Australian capacity between 2009-2012

NSSP utilised between 3-14% of industry installers across 2009-2013

Panel arrangements provided administrative benefits and

consistency in installation standards to states and territories, however, they did contribute to the low proportion of industry installers participating in the Program

9 Sustainability is now incorporated as a cross-curriculum priority in the Australian Curriculum with, in particular, solar power forming part of the science and history education syllabus. The Sustainability Curriculum Framework was established in 2010 and is expected to improve consistency and adoption.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 16

Achievements

Lessons learned

Represented a much larger proportion of mid-range (>2kW) market

Provided valuable experience in roof installations for mid-range market, including insights to resolving a range of technical issues

First ever official on roof inspections led to development of inspection checklist which has now been adopted across the industry

Two new products/services developed, including further

development of data monitoring and visualisation products and services

Overall, the Program has made identifiable, and in some cases, significant contributions towards the achievement of the NSSP objectives.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 17

1.5

Value for money

The costs of PV systems funded were largely in line with industry

benchmarks, but slightly above industry prices in the most recent years10. Analysis suggests that NSSP projects used better quality systems than industry norms which should translate to better performance and reliability, and a longer life.

The cost of abatement for funding PV systems in $ per tonne of carbon emission offset ($ / t CO2-e) was at the lower end of schemes and programs subsidising small scale solar and renewable energy11.

Small scale component Renewable Energy Target (SRET) $152-$525 Combined SRET and Feed In Tariffs, $177-$497

NSSP funded PV system, $196

150 175 200 225 250 275 300 550

[A$/t CO2]

The competitive grant process and criteria ensured funding was directed towards the projects delivering best value within each state/territory. Most states and territories put in place state wide contracts and preferred supplier arrangements using competitive processes. These arrangements typically included installation, warranty and maintenance standards to obtain consistency in quality outcomes.

The lessons learned documented earlier and following had some impact on the achievement of value for money. These included the challenges in getting the DCSVS reporting black and green data and the opportunities to improve the embedding of sustainability/energy into lesson plans of schools.

10 It should be noted that the NSSP PV cost included the cost to install the DCSVS.

11 At the lower end or below the cost of small scale solar and renewable energy generation, for example, the Solar Homes and Communities Program and that delivered by the Small Scale component of the Renewable Energy Target (SRET) and state based feed in tariffs. Sources: Productivity Commission, Carbon Emission Policies in Key Economies: Research Report, May 2011; Carbon Emission Policies in Key Economies: Responses to Feedback on Certain Estimates for Australia: Supplementary Research Report, December 2011.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 18

1.6

Sustainability

NSSP has funded a range of systems and items that will continue to deliver benefits well into the future. For example, PV systems can have a useful life of up to 30 years. These systems and items, and the supporting program material, will continue to deliver:

reduced energy being imported from the grid reduced energy consumption

reduced reliance on mains water

infrastructure and materials for teaching students about climate change

flow on impacts in behavioural change

experience for the industry in mid-range PV system installations, and data monitoring and visualisation systems

To ensure these ongoing benefits are maximised, a range of areas may require further action:

continued effort to engender commitment from more schools to embed sustainability into lesson plans

encouraging greater adoption and integration with AuSSI across NSSP schools

continuation of efforts by DRET, states and territories to resolve outstanding issues on DCSVS not fully operational, including reporting black and green energy data

maintenance strategies and plans will need to be finalised by some states to ensure the systems installed achieve expected useful life and performance

To ensure the above is achieved, and with the closure of the Program, consideration will need to be given to the ongoing role of the Australian Government (if any). However, much of the residual responsibility for the above now rests with the states and territories.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 19

1.7

Implications for the future

The achievements and lessons learned are summarised in Section 11. This includes any potential improvement opportunities to the service delivery model for future program development.

Some pertinent points in addition to those covered in 1.4 above include: The installation of a visible asset, such as solar panels and water

tanks, provided the impetus for awareness raising activities that extended beyond the students to staff and the wider community. This highlights that funding of physical infrastructure can have benefits beyond programs involving a focus purely on education and awareness raising.

Monitoring, collection and utilisation of DCSVS data was key in driving as well as measuring the effects of behavioural change and facilitating the educational activities

Quality and consistency of data collected is important to inform

whether the Program’s objectives have been achieved. This could have been improved, particularly collection of electricity consumption data pre and post implementation.

Development and implementation of a Monitoring and Evaluation Framework at the start of the program would have further assisted with the establishment of a credible baseline data and in measuring the impacts attributable to the NSSP. Evaluation activities by individual state government agencies would have further supported the evaluation efforts on a national level.

While NSSP expenditure and PV systems installed only represented a small proportion of the market, the typical size of NSSP PV installations (ie. larger than residential) provided new learnings and experience, as well as new products, which will help to further develop the mid-range PV sector. This indicates the value of government programs such as this targeting a less mature industry segment to stimulate growth. The NSSP provided an opportunity for federal and state/territory

government collaboration and as such a forum for exchanging experiences and lessons learned in the area of climate change adaptation and renewable energy policy, including as it relates to school education.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 20

1.8

Recommendations

The following recommendations have been made to ensure the sustainability of NSSP outcomes.

1. States and territories actively pursue and implement a maintenance plan/strategy to ensure the longevity of the installed systems/items and to maximise the return on the investment made

2. States and territories encourage and support regional and national networking of NSSP government schools, in collaboration with other sustainability partners, to enhance communication and assistance between schools to maximise program outcomes.

3. States and territories continue to lead efforts to embed energy and water efficiency into school curriculum

4. DRET continue to host the educational resources for schools on their website or alternatively make them available through alternative channels. For example, in Scootle.

5. DRET together with the states and territories continue to work to resolve the issues with the operation of DCSVS, ensuring green and black energy data is reported

6. Given smart meter products, such as the DCSVS, are now available and being utilised as a result of the NSSP, the option of including a module on data monitoring systems in the training of accredited installers by the Clean Energy Council should be explored by DRET. 7. DRET together with the states and territories consider the

development and implementation of an ongoing monitoring, reporting and evaluation approach to ensure the outcomes achieved through the NSSP project are kept alive and continue to be progressed. Promoting the regular collection of data and information on the schools impacts and outcomes, including cross school, jurisdiction and sector

benchmarking, should form part of these activities. The data collected should be consistent across Australia and provided to each school as feedback on performance.

8. To ensure the technical aspects of the NSSP project are understood, states and territories and non-government schools should consider professional development for teachers/school staff. Consideration needs to be given to the resources and approach required to appropriately manage the items installed.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 21

2

Introduction

2.1

Background

The Commonwealth, represented by the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE) at that time, engaged Grosvenor Management Consulting (Grosvenor) to undertake a review of the National Solar Schools Program (NSSP).

Following the Machinery of Government change in March 2013,

responsibilities for Energy Efficiency matters (including the NSSP) moved to Minister Gray, and staff associated with these functions merged with the current Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (DRET). The use of DRET throughout this report includes reference to the former DCCEE. In December 2011, an independent interim evaluation of the NSSP was conducted with a focus on the evaluation of the Program against its stated objectives.

The objectives of the NSSP are to: allow schools to:

- generate their own electricity from renewable sources

- improve their energy efficiency and reduce their energy consumption

- adapt to climate change by making use of rainwater collected from school roofs

- provide educational benefits for school students and their communities

support the growth of the renewable energy industry.

With the Program coming to a close in June 2013, the purpose of this final evaluation is to assess the effectiveness, efficiency and appropriateness of the NSSP in achieving its stated objectives and to analyse any lessons learned in order to inform future policy and program development. This includes evaluating the National Partnership Agreement on National Solar Schools Program (NPA) (delivery mechanism for government school

projects), as well as analysing the non-government school component of the NSSP, managed directly by the Commonwealth.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 22

2.2

Scope and objectives

The overall objective of the final evaluation is to assess the effectiveness, efficiency and appropriateness of the NSSP.

The evaluation’s objective will be met through an analysis of the Program’s funding approach and implementation activities of the Commonwealth and the States & Territories. Particular emphasis will be given to examining the extent to which NSSP achieved its policy objectives, taking into account the results of the interim evaluation.

Relevant parts of the NSSP review’s Terms of Reference can be found at Attachment A of this report.

This report brings together the quantitative and qualitative analyses that commenced in March 2013 and concluded with the delivery of this report in June 2013. The evaluation included an analysis of the outcomes of all NSSP funding rounds. For the final 2012/13 funding round, it was assumed that all items approved will be installed.

Evaluation approaches and outcomes of the NSSP interim evaluation were utilised for the final evaluation of the Program, where appropriate. In addition, at the time of the interim evaluation, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) undertook an independent performance audit of the Program and its operations. This included an assessment of the effectiveness of the design and the administrative arrangements.

As a result, findings, conclusions and recommendations of the final

evaluation make reference to the NSSP interim evaluation report as well as the ANAO’s Audit Report No.39 2011-12 Management of the National Solar Schools Program.

The outcomes of the evaluation activities will be key determinants for the need or priority of continued Commonwealth and State Government activities and collaboration in this policy area.

Interim report

The NSSP interim evaluation, conducted between October 2011 and February 2012, provided a number of conclusions and recommendations about the Program and its ongoing effectiveness. DRET undertook various activities to address the recommendations within the report in order to maximise the benefits achieved through the Program. Details of the

activities undertaken by DRET following the interim evaluation are outlined in Attachment B.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 23

ANAO performance audit

The ANAO performance audit assessed the Program’s establishment, implementation and administration against relevant policy and legislative requirements, and the progress towards achieving the NSSP objectives. Despite having identified a number of shortcomings in the design of the Program and the available data, the ANAO audit confirmed the Program’s achievements in meeting its objectives.

In addition, the audit concluded that the 2010/11 and 2011/12 funding rounds were well designed and effectively implemented.

The ANAO made two recommendations:

Recommendation 1 sought refinements to the content of future NSSP guidelines

Recommendation 2 focused on clearly identifying, in program documentation and advice to decision-makers, the relationship between the application scores and the assessment of proposals with respect to efficient, effective and economical use of public money. DRET agreed with both recommendations and took according actions.

2.3

The National Solar Schools Program

Overview of the program

The NSSP is part of the Government’s 2007 ‘Solar Schools – Solar Homes’ election commitment. It replaced the Green Vouchers for Schools Program and the schools’ component of the Photovoltaic Rebate Program. The NSSP commenced on 1 July 2008, and closed on 30 June 2013, two years earlier than initially planned. Savings generated were reinvested in new proposals to move Australia to a clean energy future, a Commonwealth initiative seeking to cut pollution and drive investment in clean energy sources (including solar and wind)12.

The 2012–13 funding round was the last opportunity for schools to apply for funding.

12 Refer to http://www.cleanenergyfuture.gov.au/clean-energy-future/our-plan/ for further information.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 24 The NSSP offered eligible primary and secondary schools the opportunity to compete for grants of up to $50,000, to install solar and other renewable power systems, solar hot water systems, rainwater tanks and a range of energy efficiency measures.

NSSP uptake

According to the latest data provided by DRET over 8,300 schools (88% of all schools) registered to participate in the Program. Over the life of the Program more than 5,300 schools have been awarded a grant (56% of all schools)13, totalling more than $217 million in funding.

Table 20 in Attachment C provides a summary of approved projects by state and sector.

In 2012, according to the ABS, there were 9,427 schools in Australia. This included approximately 6,693 government (71%), 1,716 catholic (18.2%) and 1,018 independent schools (10.8%).14

Timings of NSSP activities

Since its inception, the NSSP has been subject to a number of evaluation and audit activities and government reviews. The timeline below shows the key events and decisions throughout the life of the NSSP.

YEAR I FY2008/09 YEAR II FY2009/10 YEAR III FY2010/11 YEAR IV FY2011/12 YEAR V FY2012/13 Funding round 2011/12 Funding round 2012/13 20 AUG 2010 Applications close 1 AUG 2011 Applications open 13 FEB 2012 Applications open 1 JUN 2008 NSSP commences 30 JUN 2013 NSSP concludes OCT 2009 – JUL 2010 Grants temporarily suspended due to program oversubscription 15 JUL 2010 Program re-opens as competitive based program 30 SEP 2011 Applications close 18 MAY 2012 Applications close Funding round 2010/11 MAY 2011 Program funding reduced and program to close two years earlier on 30/06/2013

AUG 2011

NPA commences FEB 2012

Interim evaluation complete JUN 2012 ANAO NSSP Audit report MAR 2013 NSSP transitioned to DRET JUN 2013 NSSP final evaluation report MAR 2010 NSSP transitioned to DCCEE 15 JUL 2010 Applications open 15 DEC 2010 Grants announced 24 JAN 2012 Grants announced 30 AUG 2012 Grants announced Figure 1: NSSP timeline 13http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4221.0Main%20Features202012

14 The ABS values involve all schools including those that are not eligible for NSSP funding (e.g. other special school).

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 25

Changes to the NSSP

The NSSP commenced as a demand driven program where schools were able to submit a claim and were awarded funding if they met the eligibility

requirements of the Program.

The NSSP was over-subscribed in 2009/10 which led to the temporary suspension of the Program in October 2009. The Program re-opened as a competitive merit-based program on 15 July 2010 and the funding was capped for each financial year at a level aligned with the jurisdiction’s share of funding to manage demand.

Under the revised process, schools were required to apply in annual funding rounds and compete for funding based on three criteria including value for money, environmental benefits and educational benefits.

To address potential duplication, schools that were approved to receive funding for solar power systems under any other Australian Government program since the NSSP commenced on 1 July 2008 were only able to apply for a grant of up to $15,000 for the installation of eligible items.15

In addition, the Cabinet agreed to the establishment of a NPA with the states and territories to improve the delivery of the NSSP to eligible government schools.16

As part of the 2011-12 Budget (10 May 2011), the Government announced that the NSSP would close on 30 June 2013, and has two remaining funding rounds. Savings generated ($156.4 million) were reinvested in new

proposals to move Australia to a clean energy future. Approximately $50 million in funding remained available under the program.

The following changes came into effect from 1 July 2011:

applications from schools located in remote or low socio-economic areas received additional assessment weighting to allow funding to be directed to the most disadvantaged schools

multi-campus schools previously eligible for $100,000 had their eligibility amount reduced to up to $50,000, consistent with single campus schools. This allowed a greater number of schools to be funded under the NSSP in the final two years

for government schools - state and territory government education authorities could request that the maximum grant amount available

15 For example, schools that were approved to receive solar panels through the Building the Education Revolution (BER) program were eligible for up to $15,000 of grant funding. 16 The NPA is required under the Federal Financial Framework agreed by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) in 2009.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 26 to government schools in their jurisdiction be reduced to allow more schools to receive funding.

Schools that were approved for NSSP grant funding prior to the 2011/12 funding round were not affected by these changes to the program.

The National Partnership Agreement

As part of the Program’s re-design in July 2010, the Commonwealth required that the NSSP funding to government schools be delivered under the Council of Australian Government’s NPA arrangements.17 Prior to 2010, some state departments had a cooperative funding agreement in place with the

administering Commonwealth Department, including VIC, NSW, SA, WA and QLD. Government schools could also apply directly to the NSSP through lodgement of a claim form, in the same way as non-government schools. The NPA was formalised between the Commonwealth of Australia and the states and territories, and commenced with the first jurisdiction to sign the agreement on 5 August 201118. The NPA applied from the 2010-11 funding round.

The agreement outlines information relating to the implementation of NSSP, including:

the roles and responsibilities of the Commonwealth, and the states and territories

performance milestones and associated payments

reporting, financial and governance arrangements. The NPA is included at Attachment D.

The Commonwealth continued to directly manage non-government school projects. Successful non-government schools received their funding once an agreement had been put in place between DRET and the individual schools.

17 The NPA is available at:

http://www.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/content/npa/education.aspx.

18 ACT was the first jurisdiction to sign the NPA in 5 August 2011 with the last, VIC, agreeing to the NPA four months later on 28 November 2011.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 27

Application and assessment

The NSSP Guidelines (July 2011)19 together with the National Solar Schools Administrative Arrangements20 and Application Form Instructions provided information on the assessment process to assist schools in preparing a NSSP application.

Applications were scored against the assessment criteria and ranked from highest to lowest. Funding was then approved based on the established rankings until the funding allocation for each state and sector was fully committed.

In instances where the number of applications exceeded the funding available, those schools were ranked (highest to lowest) and included in a reserve list.

For further information refer to

http://ee.ret.gov.au/energy-efficiency/grants/national-solar-schools-program.

Governance of the NSSP

Until March 2010, the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts21 was responsible for the management and governance of the NSSP. Subsequently in 2010, DCCEE together with respective education

departments of the states and territories, managed the administration of the Program22.

DRET has the following role:

assessment of non-government school applications

management of all grants for non-government schools

communication of opening and closing dates for each annual round and announcement of successful school applications

provision of funding to the states and territories upon achievement of performance milestones

19 The National Solar Schools Program Guidelines July 2011 set out the policy parameters for the merit assessment process.

20

http://ee.ret.gov.au/sites/climatechange/files/documents/03_2013/NSSP-AdministrativeArrangements-20120502-PDF.pdf

21 Now being referred to as the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC).

22 Following the Machinery of Government change in March 2013, responsibilities for Energy Efficiency matters (including the NSSP) moved to Minister Gray, and staff associated with these functions merged with the current Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (DRET).

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 28

all aspects of program management (including developing and maintaining guidelines, development and maintenance of the NSSP grants management system, approving project variations and managing risk through implementation of a compliance plan). State/territory governments are responsible for the management and delivery of NSSP government school projects. This involved the assessment of government school applications for their jurisdiction and managing delivery of projects in accordance with the NPA.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 29

3

Approach and method

To support the evaluation activities of the NSSP, Grosvenor developed an Evaluation Strategy to provide guidance and a summary for the proposed evaluation approach.

As part of the development of the Evaluation Strategy, interview guidelines and a survey was designed and any relevant documentation, such as NSSP guidelines and reports were reviewed and assessed.

The Evaluation Strategy included:

scope and objective of the evaluation

key evaluation questions

success criteria and key indicators

key information and data sources required to assess success

outline of the evaluation methods proposed to answer the identified evaluation questions.

A graphical representation of the evaluation design, including evaluation questions, is provided at Attachment E of this report.

The evaluation was undertaken between February and May 2013.

3.1

Evaluation resources

Findings, conclusions and recommendations for the evaluation report are based on the information collected and analysed from a number of sources and stakeholders (see Attachment C for details). In addition, case studies produced by DRET with government and non-government schools across Australia, both in text and video format, were also considered and incorporated, where appropriate, in this report.23

Stakeholder consultations

Information from a variety of key stakeholders was gathered through semi-structured interviews to maximise the gathering of the information. A comprehensive set of interview questions was carefully developed that addressed the evaluation questions and also probed for the information each interviewee can uniquely provide.

23 These case studies are available on the Department’s website at www.ret.gov.au/nationalsolarschools/resources.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 30

School survey

A total of 745 schools participated in the NSSP final evaluation survey. Only complete responses (591) were considered as part of this evaluation of which 66.8% were government, 21% catholic and 12.2% independent schools. Figure 2 provides a breakdown of the number of schools in each sector and state/territory that completed the survey.

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160

ACT NSW NT QLD SA TAS VIC WA

Government Catholic Independent

Figure 2: Number of survey responses

The survey was conducted online and encompassed a mix of 33 close-ended questions with listed choice, dichotomous and open-ended questions. The latter was mainly utilised to gather information about the sustainability of the Program and to provide respondents with the opportunity to further elaborate on the ratings which they provided.

3.2

Evaluation limitations

Despite the overall confidence in the methodology and tools utilised, the evaluation must be viewed in the light of the following constraints.

Availability and quality of data

Reporting on consumption data to measure reductions in energy

consumption as a result of energy efficiency measures was one area where there was considerable inconsistencies in the quality and completeness of information provided to the Grosvenor evaluation team. This information was not collected in sufficient detail as part of the application or acquittal process and thus the NSSP relied on obtaining this information from states and territories for government schools (representing approximately 70% of all NSSP schools). The quality of data provided by states and territories varied and as a result limited the conclusions that could be drawn.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 31 WA and NT consumption data was not obtained in time to be included in the energy consumption analysis.

Grosvenor cannot verify the accuracy of the data provided; however,

quantitative and qualitative information has been triangulated to ensure the establishment of robust and tenable conclusions and recommendations.

Attributing outcomes to the NSSP

States and territories have implemented various other programs related to the subject of energy efficiency/renewable energy, as well as initiatives such as the Australian Sustainable Schools Initiative (AuSSI), a school-based environmental education program. As a result, the range of outcomes observed in NSSP schools and across jurisdictions will be, in some areas, indicative of achievements of the NSSP more generally, rather than

achievements that can be directly attributed to the work of the NSSP. This means that the evaluation explored the contribution of the NSSP, where possible, as other programs also were working towards similar goals.

Evaluating long-term impacts

Evaluating long-term impacts and outcomes achieved as a result of the NSSP is beyond the ability and scope of this evaluation because of methodological limitations and the timings of the evaluation activities. For example, the realising of sustainable behavioural changes by individual schools and their assessment as part of this evaluation has proven to be challenging. Conclusions were drawn based on the activities and the effects NSSP has made throughout the lifetime of the Program.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 32

4

Structure of the evaluation report

The final evaluation report consists of three main parts, aligned with the evaluation design. Each part contains a number of sections in accordance with the evaluation questions. Sections will draw upon the findings,

conclusions and recommendations of the evaluation, incorporating the data analysis, information from stakeholder interviews, case studies and the results of the survey.

The parts and relevant sections of the report are as follows:

Part/section Description

Part A – Input & design

Section 5– Funding approach Appropriateness of the funding mechanism

Part B – Process & implementation

Section 6 – NSSP implementation

Effectiveness of the NSSP implementation including realisation of roles and responsibilities under the NPA

Section 7 – Performance against milestones

Achievement of performance milestones I-IV under the NPA

Part C – Impacts & outcomes

Section 8 – Achievement of NSSP objectives

Achievement of each NSSP objective: Energy efficiency & renewable energy

- Objective 1 – allow schools to generate their own electricity from renewable sources - Objective 2 – allow schools to improve their

energy efficiency and reduce their energy consumption

Rainwater

- Objective 3 - allow schools to adapt to climate change by making use of rainwater collected from school roofs

Educational benefits

- Objective 4 – allow schools to provide educational benefits for school students and their communities

Supporting industry growth

- Objective 5 – to support the growth of the renewable energy industry.

Section 9 - Value for money Achievement of value for money

Section 10 – Sustainability Longevity of NSSP objectives and potential outcomes post-NSSP

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 33

PART A

–

Input & Design

This part of the report focuses on the findings in relation to the appropriateness of the funding mechanism for achieving the NSSP objectives.

In particular, the evaluation examined the appropriateness of:

annual funding rounds for each state and territory, introduced in July 2010

the maximum amount of funding for each school

payments aligned with performance milestones in the NPA.

Processes related to the assessment of applications were not assessed in detail in this report; however were reviewed as part of the ANAO audit.

5

Funding Approach

Annual funding rounds

Annual funding rounds were suitable and consistent with the approach of other grant programs

From the 2010-11 funding round, at the commencement of each annual funding round, each year’s total funding budget was allocated between the government and non-government sectors based on the proportion of eligible schools in each sector. Funding for government schools and non-government schools in each state and territory was then allocated on a similar proportion basis, taking into account any NSSP grants already awarded to schools in each state and territory. This allowed each state/territory (government and non-government sector) to receive its proportional share of funding over the life of the NSSP.

An annual competitive funding round model was established for government and non-government schools in each state and territory.

Schools competed for grants only within their state and sector. For example, New South Wales government schools only competed against other New South Wales government schools.

This approach allowed funding to be proportionally distributed to schools across the country, ensuring that all states and territories (and sectors) benefited from the Program.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 34 Budget cuts to the Program reduced the funds available for the 2011/12 and 2012/13 funding rounds by $49.8 million.24 This resulted in significantly fewer projects being able to be approved in the subsequent funding rounds. For example in the 2011/12 funding round, nearly 2,000 schools submitted applications totalling $64 million for the $25 million in funding that was available. Of those schools that applied for the NSSP grant, 787 were successful. This represented a 36% drop in the 2011/12 funding round compared to the previous year.

Feedback from stakeholders suggested that annual funding rounds were suitable and consistent with the approach of other grant programs. However, some interviews believed that the decision-timeframes for approving

applications caused various challenges. For example, by the time applications were approved and the project was able to commence,

quotations in many cases were expired and/or the product (e.g. panels) was no longer available. States and schools had the flexibility to seek new quotes to account for this delay. The variation process required that any new quote that was submitted, delivered at least the outcome that was approved and therefore, the competitiveness of the application was not reduced.

The most significant delay occurred in the 2010/11 funding round due to delays in agreeing the NPA, further detailed in Section 7.2 of this report. DRET believed thatthe period in which applications were assessed, approximately six weeks, was appropriate, as it provided assurance that applications were correctly assessed andthe most meritorious applications in each state and sector were awarded funding.

However, it is acknowledged that the announcement of successful schools was noticeably deferred, following the completion of the assessment process. For example, successful schools for the 2011/12 funding round were announced by the responsible Minister on 24 January 2012, almost four months after the application closing date. Similarly, the outcomes of the 2012/13 funding round were announced three months after the application closing date, on 30 August 2012.

Four jurisdictions were affected by spring holidays in the 2011/12 funding round.25 While this abbreviated the period in which schools could apply, it allowed approximately six weeks for the submission of applications.

24 $25mil for the 2011/12 funding round and $24.8mil for the 2012/13 funding round 25 Holidays TAS: 3 Sep – 18 Sep 2011; QLD: 19 Sep – 30 Sep 2011; NSW: 24 Sep – 9 Oct 2011.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 35 State and territory education departments were responsible for all aspects of the project implementation for government schools with Commonwealth funding only provided for the on-grounds works. For that reason, most state/territory interviewees suggested that a NSSP administrative budget would have been of benefit to assist with the management and

implementation of the Program. Education authorities struggled to provide sufficient support, as they were impacted by competing priorities from other programs and most notably cuts to their own agency’s budget.

Dedicated personnel were identified as a key success factor in enabling the achievement of the Program’s outcomes, in particular in achieving the educational benefits.

The majority of states/territories were able to provide as a minimum a part-time employee (three days a week) dedicated to the management and implementation of the NSSP with some additional assistance from other staff members of the department.

However, stakeholders stated that greater financial assistance would have helped with the administration, promotion and reporting for the Program, as well as supplying educational support to ensure NSSP objectives are being achieved.

Funding amount

The maximum grant amount was considered appropriate

The NSSP offered grants up to $50,000 for single campus schools and, prior to the 2011/12 funding round, up to $100,000 for eligible multi-campus schools to install solar power systems, rainwater tanks and range of renewable energy efficiency measures.

Schools that planned to install less than 2kW or no solar power system were eligible to apply for up to $30,000 for the installation of eligible items. In addition, those schools that received Green Vouchers for Schools funding had this amount deducted from their NSSP grant.

From the 2010-11 funding round onwards, schools that were approved to receive funding for solar power systems under the BER were eligible for up to $15,000 in NSSP funding.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 36 ACT, QLD, NSW and SA requested that the maximum grant amount for their government schools be reduced, following the reduction in budget

announced in May 2011. ACT and QLD government schools were eligible to apply for maximum funding of $25,000. Similarly, NSW government schools are eligible to apply for up to $33,000; and SA government schools,

$30,000.

All stakeholders interviewed believed that the maximum grant funding amount was appropriate for schools to secure solar power systems (and/or other items) of sufficient size to have a positive impact on the school’s environmental footprint and to educate students and the wider community about renewable energy and energy efficiency.

As detailed in Section 8.1, the cost per kW for a solar power system decreased significantly over the duration of the Program. Those schools participating in later funding rounds were therefore able to purchase larger solar PV systems.

The maximum amount of grant funding was not influenced by school size, therefore smaller schools experienced greater visible benefits in reducing their energy bills, in comparison to larger schools, who whilst achieving an offset in their electricity usage, generally did not notice a significant difference in their electricity bills.

A third of all NSSP schools (government and non-government) received additional government and/or private funding over and above the maximum NSSP grant amount. The decision by some states to combine state funding with the NSSP funding increased benefits obtained by the school. Over the life of the NSSP, QLD, WA, ACT and VIC had programs in place that

supplemented NSSP funds. Details of these programs can be found in Table 1 in Section 6 of this report.

Payments aligned with performance milestones

Under the NPA, states and territories obtained 50% of the annual funding amount up front upon the provision of a list of approved government school projects for the funding round, and the remaining 50% of funding, once all approved projects in the state and territory were completed.

Once the milestone was achieved, payments were scheduled with the

Treasury, who made payments to the states and territories on the 7th day of each month.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 37 The 50/50 payment model attached to the performance milestones

represented the most contentious element of the funding approach. State and territory education representatives reported that the approach was not practical, causing additional financial and administrative burden to the state and territory government agencies.

While many stakeholders felt that the approach should have been identical to the non-government payment model, detailed below, the milestone payments were consistent with the agreed NPA framework. During NPA negotiations, administrative reporting for states and territories was reduced and the value for the first payment increased. In addition, it is the

Commonwealth’s view that states/territories were in an appropriate position to effectively manage the cash flow and meet the costs associated with the implementation of NSSP projects.

In contrast, non-government school grants were directly administered by the Commonwealth. One-off grant payments were made by DRET to respective non-government schools, once a funding agreement was signed. The funding agreement required non-government schools to complete the project within a specified time period and included reporting requirements during and upon completion of NSSP projects. A range of controls allowed the Commonwealth to recover any funds if necessary in the event the funding agreement with the school was breached.

However, it should be noted that his approach was not aligned with the principles of the ANAO’s Better Practice Guide Administration of Grant (May 2002).26 The guide outlines that it is good practice to retain a portion of the grant funds until the recipient has completed and fully acquitted the project as this provides an incentive for funding recipients to comply will all

obligations set down in the funding agreement. It can be argued that a model for non-government schools closer aligned to the ANAO’s Better Practice Guide would have been more appropriate for the management of the NSSP.

Department of Resources Energy and Tourism grosvenor management consulting 38

5.1

Conclusions - funding approach

As expected the budget reduction in May 2011 resulted in not all schools being able to benefit from the NSSP. However, the move from a demand-driven grant program to a competitive, merit-based selection arrangement was a positive and effective development. The design of the program could have considered a merit based model from the outset to account for the possibility that demand exceeded funds available in a given financial year. The annual allocation of funds allowed each state and territory (and sector) to receive a proportional share of funding over the life of the Program. While prolonged timeframes for announcing successful applications caused a

variety of challenges, the guidelines provided the flexibility for new quotes to be sourced.

The maximum NSSP grant amount per school was sufficient in that schools were able to install PV systems and other energy efficiency items that resulted in a reduction of the schools’ environmental footprint. Where NSSP funding was supplemented by state/territory or school contributions, greater benefits were achieved.

Smaller schools noticed a more visible impact on their electricity bills, whilst larger schools with significant energy consumption did not notice a material change.

While the states and territories raised concerns about the lack of funding of administration, it is not unreasonable to expect that some contribution should be made by the states and territories, particularly given the potential for a reduction in energy and water costs and the benefits obtained for government schools.