Team Development and Team

Performance

Responsibilities, Responsiveness and Results;

A Longitudinal Study of Teamwork at Volvo Trucks Umeå

Published by: Labyrint Publications

PO Box 334

2984 AX Ridderkerk

The Netherlands

Tel: +31 (0)180-463962

Printed by: Offsetdrukkerij Ridderprint B.V., Ridderkerk

ISBN 90-5335-060-8

© 2005, B.S. Kuipers

Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen, of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de auteur.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system of any nature, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying or recording, without prior written permission of the author.

Team Development and Team Performance

Responsibilities, Responsiveness and Results: A Longitudinal Study

of Teamwork at Volvo Trucks Umeå

Proefschrift

ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Bedrijfskunde

aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de

Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op

donderdag 7 juli 2005 om 14.45 uur

door

Benjamin Stanley Kuipers geboren op 18 augustus 1975

Copromotor: Dr. M.C. de Witte

Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. dr. E. Molleman Prof. dr. S. Procter Prof. dr. A.M. Sorge

First of all, I would like to address the reader who is curious as to what this book about teamwork might bring. Let me tell you up front: dissertations are not known for being read thoroughly, so don’t be bothered too much about that. Actually, I would already be happy when each of you manages to find just one useful thing in this book to improve your way of working with others and enjoying it.

But before you start, you may wonder what inspired me to make a four-year study of teamwork, spending months and months in the North of Sweden and ages at my desk writing this dissertation. That’s easy to explain. It’s because the world is full of beautiful and inspiring things: the clean air and sultry midsummer nights 300 km below the polar circle*, the forgetting-everything-around-you music and lyrics from bands like Coldplay**, the fascinating words from books like Funky Business*** and the brightly colored impressionistic landscapes by Van Gogh**** (the painter). Most of all, it’s just the plain simple people like you and me trying to accomplish something together.

Let me set you at ease: the path to a dissertation is not just full of clichés like those mentioned above; there are actually a lot more. It also takes some pretty lonely days at the computer, some tough struggles to get valuable questionnaires back from a few respondents, some really frustrating moments with figures that don’t look like you want them to, and indeed those stubborn colleagues who believe their theory of reality (which they never even saw) is best. But what the heck, it could have been worse! Try to imagine life as a PhD candidate with 760500 responded items, but then without a computer (actually there were more, but calculating these precisely would involve me sitting at my desk even longer). These “unreliable” respondents did give me a good story and the bad figures did help me think over my theory more carefully. So what’s left now are these unworldly colleagues; but since I’m one of them, things actually seems to be pretty much back to normal. To be honest, my four years and several months of working on this research gave me a lot of fun, important new insights, great experiences, many new friends, and my girlfriend. All these things can’t be captured in a book like this, nor on a page with a few acknowledgements. In a sense, everyone in their own way contributed equally to this work, though some more equally than others. I’ll try to name a few of the most equal ones here.

First of all, I would like to thank the four people who formed both the basis for the research project leading to this dissertation as well as the platform for my professional career. My supervisors in Groningen, Ad van der Zwaan and Marco de Witte, who by their coaching showed what “steering of self-organization” means in practice and how to reach something in science. With Peter Hertinge and Mona Edström-Frohm from Volvo in Umeå I experienced the value of real teamwork by accomplishing something together in a large organization like Volvo. Also, I would like to thank all my other friends (some of whom are also colleagues) in and from Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia, Germany, The United Kingdom, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, Canada, The United States, Colombia,

relationships. I would also like to thank my family: my mother, father and sister, oma and opa (who unfortunately is not with us anymore to see me becoming a doctor), and my uncles, aunts and cousins, who are always there for me. A special thanks goes to Natasha, who always looks at science with common sense and after me with love. Furthermore, I would like to thank the members of the examination committee for their time and valuable feedback. Last but not least, I need to thank the more than 2200 employees and managers of Volvo Umeå who provided me with all the valuable data and patience during all those years of research. These people showed me what teamwork and organizations really are. And finally, according to good Swedish custom: “kram till er alla”!

Ben Kuipers

‘s Gravenhage, May 2005

benkuipers@yahoo.com

* If you are interested to find out, beware that the Umeå tourist office has very limited opening hours.

** “I was just guessing at numbers and figures Pulling the puzzles apart

Questions of science, science and progress Do not speak as loud as my heart

Tell me you love me, come back and haunt me Oh and I rush to the start

Running in circles, chasing our tails

Coming back as we are” From: The Scientist by Coldplay (2002) (source: www.coldpaying.com)

*** “Reasoning is what the typical manager is rewarded for. Eventually the analytical side of the brain grows so large and heavy that some executives find it difficult to avoid walking in circles.” [p.273] From: Funky Business by K.A. Nordström and J. Ridderstråle (2000) **** For those who hate museums, we have two cheap repro’s hanging in our living room.

Contents

PART I INTRODUCTION: Model and study

1

Chapter 1 Introduction 2

1.1 Trends in Teamwork: Theoretical traditions 2 1.2 Trends in Teamwork: Practice-based literature 5 1.3 Trends in Teamwork: Scientific literature 6

1.4 Trends in Teamwork: A research agenda 8

1.5 Trends at Volvo 9

1.5.1 The Volvo Umeå site: Processes and departments

descriptions 10

1.5.2 Work teams at Volvo Umeå 12

1.6 Overview of content 13

PART II

RESPONSIVENESS: Dimensions of team

responsiveness and their relations to team

responsibilities and team results

14

Chapter 2 Responsiveness: Processes of work teams 15

2.1 Introduction to the literature 15

2.2 Phase models and process models 17

2.2.1 Consultancy phase models 17

2.2.2 Sociotechnical phase models 19

2.2.3 Recurring phase models 22

2.2.4 Critics to phase models for work teams 23

2.2.5 Process models 24

2.3 Towards a new model for team responsiveness and team

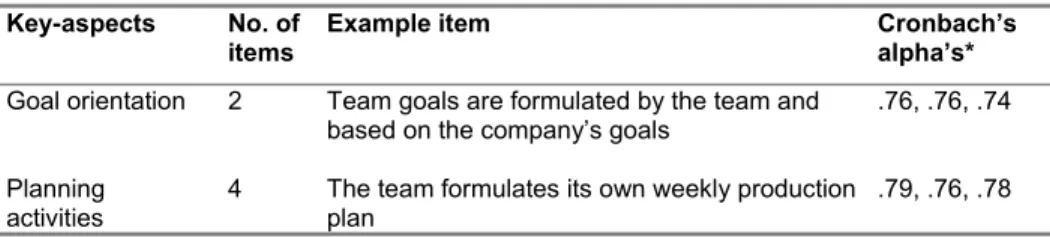

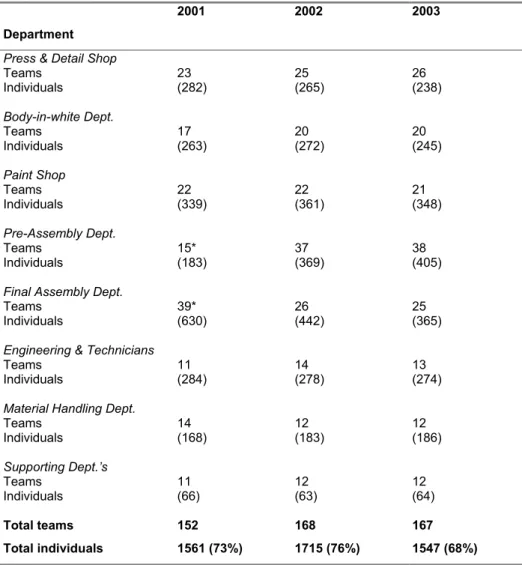

2.4.1 Data and sample 29

2.4.2 Results of factor analyses 31

2.5 Three dimensions of team responsiveness 33

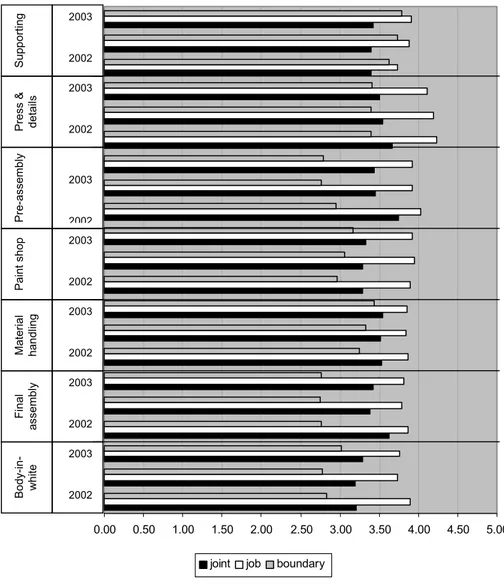

2.6 Team responsiveness at Volvo Umeå 35

2.7 Conclusions 37

Chapter 3 Concepts and methodology for responsiveness

and results 38

3.1 Introduction to the literature 38

3.2 Models for team results 40

3.3 Relating team responsiveness to team results 42 3.3.1 Hypothesizing cross-sectional effects of responsiveness

on results 43

3.3.2 Hypothesizing the longitudinal effects of responsiveness

on results 45

3.3.3 Summary 46

3.4 Methodology and measures 46

3.4.1 Methods for the statistical analysis 46

3.4.2 Measures of business performance 48

3.4.3 Measures of quality of working life 50 3.5 Further specification of hypotheses and methods 51

PART III

RESULTS: Effects of team

responsiveness on business performance and

quality of working life

53

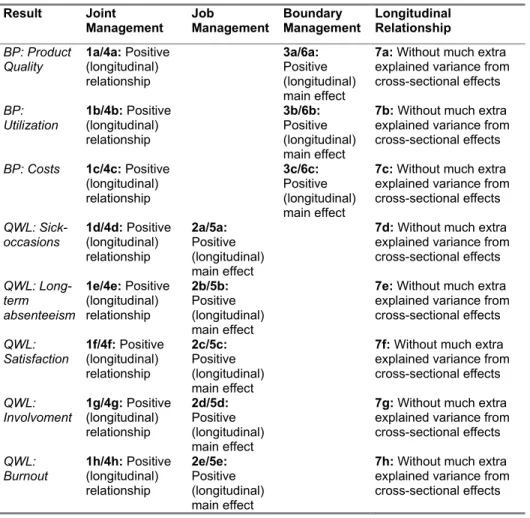

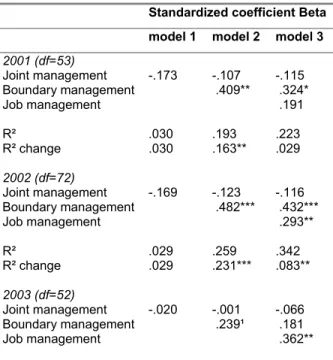

Chapter 4 Team responsiveness and business performance 54 4.1 Direct effects on business performance 54

4.1.1 Product quality 55

4.1.2 Utilization 57

4.1.3 Costs 57

Chapter 5 Team responsiveness and the quality of working life 63 5.1 Direct effects on quality of working life 63

5.2 Behavioral outcomes 64 5.2.1 Sick-occasions 64 5.2.2 Long-term absenteeism 65 5.3 Attitudinal outcomes 67 5.3.1 Satisfaction 67 5.3.2 Involvoment 68 5.3.3 Burnout 70

5.4 Longitudinal effects on quality of working life 71 5.4.1 Longitudinal effects on behavioral outcomes 71 5.4.2 Longitudinal effects on attitudinal outcomes 73 5.5 Summary and conclusions on quality of working life 77

PART IV

RESPONSIBILITIES: Complexity and

location of regulation tasks and their relationships

with team responsiveness

81

Chapter 6 Responsibilities: Management structure of the

team-based organization 82

6.1 Introduction to the literature 82

6.2 Operating and managing systems 84

6.3 Responsibilities and the management structure 86 6.4 Characteristics of the regulation tasks 87

6.4.1 Complexity of regulation tasks 88

6.4.2 The location of regulation tasks 88

6.5 Relating team responsibilities to team responsiveness 89 6.6 Methods and measures of the management structure 92

6.6.3 Measures for location 93

6.6.4 Methods and summary of hypotheses 94

Chapter 7 Team responsibilities and team responsiveness:

Exploring the relationships 97

7.1 Selection of crucial regulation tasks 97

7.2 Characteristics of the management structure 99

7.2.1 Regulation task complexity 100

7.2.2 Regulation task location 102

7.3 The relationship between complexity and location of regulation tasks 104 7.4 The effects of location on team responsiveness 106 7.4.1 The effects of the proximity of authority and expertise 106 7.4.2 The effects of the number of regulation tasks 110

7.5 Conclusion 114

PART V

GENERAL CONCLUSIONS: Findings,

model, further research and practical applications

116

Chapter 8 Conclusions and discussion 117 8.1 Team responsibilities, responsiveness and results 1178.1.1 Team responsiveness 117

8.1.2 Team results 118

8.1.3 Team responsibilities 119

8.2 Three R’s: a model for team development 120 8.3 Strengths, weakness and further research 122

8.3.1 Strengths 122

8.3.2 Weaknesses 122

8.3.3 Further research 123

8.4 Applications of the 3R-model 124

8.4.1 Limitations of phase theories for practical use 124 8.4.2 Starting team development from the results perspective 125 8.4.3 Practical steps for developing teams 125

References 131

Appendix A. Factor loadings 140

Appendix B. Factor congruence test 142

Samenvatting 145 Summary 153

Chapter 1

Introduction

This first chapter of my dissertation will provide the reader with some insights into the concepts, theories and trends regarding teamwork and work teams. My study takes place in the automotive industry, which often strikes the imagination, and which teamwork experiments received much attention in managerial and scientific literature. After illustrating its background I will develop an agenda and first model for my research. I shall finish this chapter with an introduction of the Volvo plant in which I studied more than 150 teams during a three year period. An important message, which I will underline throughout this dissertation, is that teamwork can never be a goal in itself.

1.1 Trends in Teamwork: Theoretical Traditions

Working in groups has been studied since the twenties of the last century (Beyerlein 2000; Buchanan 2000; Van Hootegem et al. 2005), with the Hawthorne studies as one of the first and most famous examples. Groups have been subject to studies in various forms and in the 1950s the literature on group processes started to be referred to by the term group dynamics. Lewin (1947) introduced this term, describing group dynamics as “the way groups and individuals act and react to changing circumstances” (Forsyth 1999). Social psychological perspectives in general and group dynamics in particular not only involve teamwork, but all possible types of groups. Forsyth (1999) sees the concept of “work teams” as a special application of groups in “business, industry, government, education, and healthcare settings … lying at the foundation of the modern organization.”

By now “almost all of us work in teams” (Sheard & Kakabadse 2003), and the term in itself seems to be inflated. Teamwork did become very fashionable, especially during the 1990s (Van Hootegem, Benders, Delarue, & Procter 2005) and so far I have not met anyone denying to work in a team, in one way or another. This raises the question of what teamwork is and I maybe disappoint the reader by telling that there is no one single answer to this question. Throughout this dissertation you will find that different authors use different perspectives, dependent on different

backgrounds and different interests; group work does not automatically imply work groups and vice versa1.

Group dynamics as a concept covers group work in general, varying from studies of therapy groups to laboratory studies. The concept of working groups covers to a large extent the literature concerning groups in organizations. The general applied term team is mostly used for this latter type of groups and defined as:

“A collection of individuals who are interdependent in their tasks, who share responsibility for

outcomes, who see themselves and who are seen by others as an intact social entity embedded in one or more larger social systems (for example, business unit or the corporation), and who manage their relationships across organizational boundaries” (Cohen & Baily 1997).

Within this definition a distinction can be made between management teams, project teams and work teams (Cohen & Baily 1997; Sundstrom et al. 2000). Generally management teams consist of several managers, who steer entire organizations or parts of organizations. Project teams are “time-limited” (Cohen & Baily 1997; Sundstrom, McIntyre, Halfhill, & Richards 2000) and carry out specified projects, often consisting of a variety of different experts. Work teams are divided by Sundstrom et al. (2000) into ‘Production groups’, consisting of “front-line employees who repeatedly produce tangible output”, and ‘Service groups’, consisting of “employees who cooperate to conduct repeated transactions with customers”. Both groups are referred to by various terms such as semi-autonomous, self-regulating, self-managing, self-directed or empowered teams. These teams need to be distinguished from parallel teams, such as quality circles. Semi-autonomous work teams are everyday working teams, with their members working full-time together on the joint production or service tasks, while “parallel teams pull together people from different work units or jobs to perform functions that the regular organization is not equipped to perform well” (Cohen & Baily 1997). This study focuses on the concept of work teams, which is embedded in two general traditions, which I name briefly here to grasp the field of study. These two traditions are the sociotechnical systems theory (STS) and the Japanese Lean Production (LP) (Kuipers, De Witte, & Van der Zwaan 2004; Procter & Mueller 2000), also called the “team” and “lean” approaches (Applebaum & Batt 1994) or “anti-Taylorism” and “neo-Taylorism” (Pruijt 2003). Several articles and books are available that compare and distinguish between the two (Adler & Cole 1993; Benders & Van Hootegem 1999; Benders & Van Hootegem 2000; Berggren 1994; Jürgens 1992; Procter & Mueller 2000; Van Amelsvoort & Benders 1996). An

1

People can do group work without being a (formal) work group, they also can be member of a work group but not working as a group.

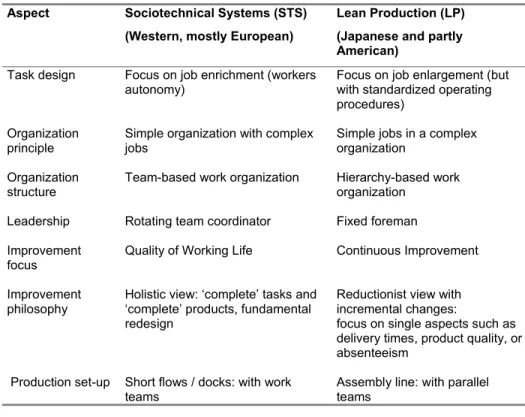

overview of the differences between them based on this literature is given in the following table:

Table 1 Differences in Team Concepts: The Sociotechnical Systems Theory Versus the Lean Production Approach

Aspect Sociotechnical Systems (STS) (Western, mostly European)

Lean Production (LP) (Japanese and partly American)

Task design Focus on job enrichment (workers autonomy)

Focus on job enlargement (but with standardized operating procedures)

Organization principle

Simple organization with complex jobs

Simple jobs in a complex organization

Organization structure

Team-based work organization Hierarchy-based work organization

Leadership Rotating team coordinator Fixed foreman Improvement

focus

Quality of Working Life Continuous Improvement Improvement

philosophy

Holistic view: ‘complete’ tasks and ‘complete’ products, fundamental redesign

Reductionist view with incremental changes:

focus on single aspects such as delivery times, product quality, or absenteeism

Production set-up Short flows / docks: with work

teams Assembly line: with parallel teams

LP is often seen as an effective work organization concept in mass production, while STS is considered to be more effective in production environments with lower volumes and more customer specifications (Van der Zwaan & De Vries 2000). Despite many combinations in business practice, which bring the traditions closer together (Adler & Docherty 1998; De Leede & Looise 1999), LP and STS nonetheless are still seen as theoretically different concepts and recognized as different solutions for different situations (Adler & Cole 1993; Niepce & Molleman 1998). The teams I studied at Volvo, and the concepts applied there, do not mind the debate and show characteristics of both, dependent on what comes at hand.

1.2 Trends in Teamwork: Practice-based Literature

From the 1950s with the ‘discovery’ of sociotechnical teamwork in the British coal-mines (Trist & Bamforth 1951) to the early 1980s, the sociotechnical approach grew steadily in popularity among a select group of practitioners and researchers within (predominantly) the manufacturing industry. Indian textile mills (Rice 1953), Norwegian power-plants (Emery & Thorsrud 1964), car factories like Volvo Kalmar (Blackler & Brown, 1978) and Volvo Uddevalla (Berggren 1994; 1993) are just a few of the famous examples on a long list of experiments with sociotechnical principles for improved working conditions and increased productivity and quality in industry (Van Eijnatten 1993). However, the ‘big-bang’ for teamwork maybe only arrived at the end of the 1980s and in the early 1990s. “Where the ‘semi-autonomous work groups’ of the 1970s have remained a marginal phenomenon, the ‘self-managing teams’ of the 1990s have become a contemporary organizational ideal” (Van Hootegem, Benders, Delarue, & Procter 2005). This is the period of well-known and often cited books, usually written by business-consultants, like The Wisdom of Teams (Katzenbach & Smith 1993), Empowered Teams (Wellins, Byham, & Wilson 1991), The Machine that Changed the World (Womack, Jones, & Roos 1990) and The Volvo Experience (Berggren 1993). Self-managing teams became high fashion and were said to boost business performance and quality of working life.

Now, ten years later, the word “team” is still left and the words “empowered”, “self-directed” or “self-managing” seem to have lost their glitter and glamour. With the current economic low-tide after the year 2000 and the continuous pressure on (Stock-Exchange listed) companies to further reduce costs, it looks like sociotechnical practices at the industrial workplace are exchanged for the well-known recipes of line-production, centralization, standardization and old-fashioned cost-cutting, now often (unjustly) referred to as “reducing non-value added operations”.2 The focus is, more than ever, on the “hard outputs” of the

organization, its units and its individuals. Lean Production is often said to suit these demands very well. In a recent special issue of IJOPM on the changes taking place within the former sociotechnically inspired Volvo production system, the editor compares LP with a steamroller. “Nothing much has been able to stand in the way of the juggernaut of “lean production” as it stretches its hegemony into more and more areas of organizational life” (Wallace 2004). Many organizations seem to follow each other on the path “back to the driven line” (Andersson 2002). However,

2 This clearly should not be confused with “Toyota’s strategy of conserving resources”

(Johnson & Bröms 2000), which many organizations deem to follow. Johnson and Bröms specifically state that “cutting costs by eliminating nonvalue activity…is central to recently popular process improvement initiatives…none of which really captures the essential point of conserving resources by avoiding – not eliminating – waste” (2000: 32).

in the world of Karaoke Capitalism the following is said about such tendencies in today’s business:

“Our world is full of karaoke companies. In business there are even names for this imitation frenzy: benchmarking and best practice – as if these fancy labels would make a difference. Let’s face it. No matter what the pundits say,

benchmarking will never get you to the top – merely to the middle.” (Ridderstråle & Nordström 2004)

The suitability of the LP versus STS concepts in the automotive industry has been elaborated in works such as those written by Womack, Jones, & Roos (1990) and Adler & Borys (1996), as well as in the NUMMI versus Uddevalla discussion between Adler and Cole (1993) and Berggren (1994). These authors discuss which of the two approaches is the best design for an automotive plant. Kuipers, de Witte & van der Zwaan (2004), however, note that they cannot adequately compare the outcomes of the design, since they do not compare the improvement in performance, let alone a comparison, over time.3 This brings me to my main criticism: so far the debate has mainly dealt with designs for teamwork (Adler & Borys 1996) while overlooking developmental processes as well as their outcomes. In other words, it has concentrated on the design of the production structure of either LP or STS and did not take into consideration the processes and products after the implementation. In short, my study does not focus on the question of which approach is the most suitable, but on the issue of development and the outputs of this development after their implementation.

1.3 Trends in Teamwork: Scientific Literature

Contemporary management literature has made many promises to organizations concerning the successes that the implementation of work teams would bring. As the hype seems to have passed, the question rises whether teamwork has not been that successful as expected, or did not meet the promises made. To evaluate this we need to turn to the scientific literature that has brought forward a great deal of theoretical and empirical work on work teams from the early start to right after the hype today.

With the increasing interest of managers for adopting quality circles and group work, Bettenhausen (1991) identified and reviewed 250 studies on “behavior in organizational work groups”, published between 1986 and 1989. He summarizes a large number of topics discussed in these studies, ranging from social-loafing to

3

Only Parker (2003) presented a study that tested for the LP-design effects in a longitudinal study, in which negative effects were observed for employees in lean production groups.

group effectiveness, to “provide insight for the management of work groups” (Bettenhausen 1991). In 1997 Cohen and Bailey follow up on the work of Bettenhausen with an original selection of 200 articles in the period from 1990 to 1996. Their agenda and demands on the studies to be included in their review are already much more strict than those used by Bettenhausen (1991), and therefore they only “focused on 54 studies of teams in organizations that included measures of effectiveness” (Cohen & Baily 1997). Work teams, “the type of teams most people think about when discussing teams” (Cohen & Baily 1997), are represented in only 17 of the reviewed studies that meet their conditions for measuring effectiveness; the rest concerned parallel teams, project teams and management teams. An alternative review is provided by Sundstrom et al. (2000), who selected 90 field experiments and field studies between 1980 and 1999 that took place in “actual work settings” and that “measured some facet of work group effectiveness”. Of these studies 15 concentrated on production teams and 30 on service teams, while those remaining concerned other types of groups such as management teams and projects teams (Sundstrom, McIntyre, Halfhill, & Richards 2000). I will come back to these studies in later chapters.

The overviews provided by these authors indicate the relatively small amount of “in-context” studies4 (McGrath 1986) during the past two decades conducted on

work teams in relation to performance. On the other hand, they do show the wide variety in research topics within this field, ranging from groupthink to production structure design. A few aspects in the reviewed works need to be highlighted. The terms performance or effectiveness, for instance, are used very generally and often in relation to very different measures, ranging from satisfaction to perceived effectiveness. Dunphy & Bryant (1996) indicate that team performance is not a unitary construct. Nevertheless, many studies apply different performance measures to come to general conclusions like “teamwork is effective or not”, thereby disregarding that they might have fetched only a tiny bit of the overall perspective on performance. On the other hand, much more attention is paid towards the inputs to and the characteristics of teamwork. Again though, most of such variables concern conditions or structural aspects and only few studies include process variables over time.

Coming back to the demands put on managers and organizations (not only nowadays), I believe there is a clear need to further develop understanding of the inputs, processes and outputs of work teams. Bettenhausen’s question (1991) to gain further insight in the management of teams still remains largely unanswered. Many of the contemporary literature, but also many scientific authors have been overemphasizing the design of work teams and teamwork. As Van Hootegem et al.

4

McGrath (McGrath 1986) defines “the study of groups in context” as one of the specific needs for studying groups at work. “…It is a far more complex question than the simple argument about whether to study groups in the lab or the field”. To study groups in-context e.g. means studying teams within time and embedded within organizations.

(2005) put it: “there is more to implementing teams than setting up the proper organizational structure”. Personally, I would like to add that the effectiveness of teams should receive full attention, and that the slowly growing idea in practice that teamwork is some kind of goal in itself should be tackled. Even more focus needs be put on the exact outcomes of work teams, so we can improve our knowledge and tools, and get from teamwork what we wanted to get in the first place: organizational success (Cohen & Bailey, 1997).

1.4 Trends in Teamwork: A Research Agenda

Since the original input-process-output model of teamwork (McGrath 1964) several other models have been elaborating on McGrath’s baseline (Yeatts & Hyten 1998). McGrath (1964) originally approached the process aspect as a black-box yet many years later noticed that researchers still hardly paid attention to patterns in group behavior to gain better insight into this process (1986). Campion et al. (1993) say about process that it “describes the things that go on in the group that influence effectiveness”. Therefore I consider the team process as indispensable on my agenda, which aims to develop better knowledge about the outputs of work teams and the activities that can be employed to improve these outputs in organizations. As I see it, this agenda for teamwork consists of three basic issues around the inputs, processes and outputs of work teams:

• The management of work teams: deeper understanding is required of the management structures as input to the team processes.

• The processes of work teams: further insight is required in the patterns of the team processes over time.

• The results of work teams: more thorough knowledge of the team’s actual performances are required.

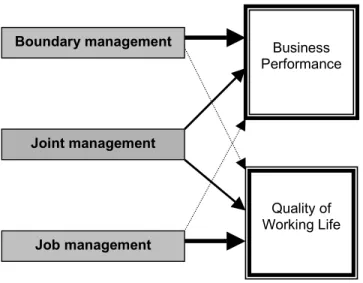

In other words, there is a need for an input-process-output model on teamwork that demonstrates the management needed to develop the team processes that provide clearly defined results. This overall model concerns team development in which both the process as well as the conditions and results of work teams play a central role. For this basic model I have used a different terminology. The inputs to teamwork consist of a set of conditions and structures, varying from task design to group composition and HR-tools. I am specifically interested in the management structure. Among other things, the managing structure shapes the maneuvering space of the team, i.e. the responsibilities of teams. The processes of teamwork, in terms of actions and behavior, reflect the ways in which teams respond to these given responsibilities. These processes will therefore be named responsiveness. The outputs of teams are the business performance (BP) and the quality of working life (QWL); they are the result of the team’s responsiveness. The overall basic model is but a simple input-process-output model, see Figure 1:

Figure 1 Conceptual model of team development

These three ‘umbrella’ terms will be used and further elaborated theoretically and empirically.

The heart of this model is responsiveness. Earlier on I described the concept of group dynamics, which is closely related to responsiveness. One could say that responsiveness is a special application of group dynamics to work teams. It is important to properly define responsiveness before elaborating the inputs and outputs. In short, this dissertation aims to answer the following three research questions:

1 Team responsiveness: how can the team developmental processes be described?

2 Team results: what are the effects of the team responsiveness on business performance as well as on quality of working life?

3 Team responsibilities: what are the management structure’s inputs that generate team responsiveness?

These three questions will be answered with this study at a Volvo Trucks plant in the North of Sweden: Volvo Umeå. The next section will introduce the reader to this organization and its developments, an elaboration that is needed to understand the process and outcomes of this study.

1.5 Trends at Volvo

In 1.2 I mentioned Volvo’s place in the history of the sociotechnical approach thanks to its famous work organization experiments. Volvo is well known for its experiments with teamwork in their former car division (Adler & Borys 1996; Womack, Jones, & Roos 1990). However, researchers are less familiar with Volvo’s similar work in their truck and bus divisions (Blackler & Brown 1978; Berggren 1993; Sandberg 1995; Thompson & Wallace 1996). With the publication of “The Machine that Changed the World” (Womack, Jones, & Roos 1990), a debate started between advocates of Lean Production (LP) and of Sociotechnical Systems (STS) ( for a brief description of this debate see: Kuipers, De Witte, & Van der Zwaan 2004). The debate mainly addressed the suitability of these approaches

Team

Responsibilities ResponsivenessTeam Results Team

in the automotive industry and died down after the dismantling of the Volvo Uddevalla plant, which was considered to be the prime example of sociotechnically based production. Thereafter, lean production practitioners and many manufacturers in the automotive industry took LP to be the more effective concept (cf. Womack, Jones, & Roos 1990; Sandberg 1995). This debate in the automotive industry apparently then came to a standstill; however, STS continued to be used in truck and bus production, a practice that received little attention in contemporary management literature. One of the truck plants that continued experimenting with semi-autonomous work teams and a sociotechnical-based production organization is the European cab-plant of Volvo in Umeå, Sweden.

1.5.1 The Volvo Umeå Site: Processes and Departments Descriptions

Volvo Umeå is Volvo’s European manufacturer for all FL, FM and FH models of truck cabins (Kuipers & De Witte 2005a). This plant builds 55,000 cabs annually, mostly for the European market, from steel plate to completely fitted cabs, which are delivered to the Volvo Truck plants in Gothenburg and Gent. The plant contains five production departments, each responsible for a part of the cab-manufacturing process. The production process is supported by a number of other departments, of which logistics and engineering are the largest. A brief description of each of these departments, that together employ around 2200 people in the plant, follows below.

The press and detail shop includes a press line, two door lines, a detail shop, a special cab dock and a spare parts division. In the highly automated press line all the cut steel is pressed into floors, fronts, sides, rooftops and doors. The door lines weld all sorts of doors for Volvo’s FL, FM and FH cabs. In the less automated detail shop and other shops, operators work at a variety of machines pressing parts or components, they produce special cabs (e.g. crew cabs), or pack spare parts and completely knocked-down cabs. These CKD cabs are sent to smaller assembly facilities of Volvo and Volvo partners all around the world. About one fifth of the total production of Volvo Umeå consists of such CKD-packages.

The body-in-white department is the welding line of the Umeå plant and basically it consists of three main (product) flows. In the FM and FH lines the majority of the work is done by robots, while the FL line (with the lowest volume) is less robotized. The moderately repetitive work is divided into preparation, parts welding and complete cab welding. In order to escape the repetitiveness of the work, operators rotate on a weekly basis.

The paint-shop receives the fully welded cabs from the body-in-white department. During a highly advanced production process the cabs are first cleaned, after which they receive a primer bath and, several sequential steps further, the final paint-layers (“in any desired color”). The painting-process shows typical characteristics of process industry: the sub-processes are highly interrelated, requiring perfect conditions of the product (body-in-white), the paint mixtures and the environment (totally dust-free and specific climate conditions).

In the assembly area the complete cab is trimmed and made ready to be as-sembled at Volvo Gothenburg or Gent (Kuipers & De Witte 2005a; Thompson & Wallace 1996). Ninety percent of the work during this process is performed manually, and as a result over one third of the plant’s operators work in this area. Until the end of 2001, the shop floor for cab trimming consisted of about 20 short-flows and 10 dashboard-shops. The organization of the assembly area back then consisted of two identical departments, each responsible for about half of the production. The short-flow layout is a unique concept of entirely parallel short production lines in which a team is responsible for the trimming of an entire cab. In a well-trained team the workers are able ‘to follow’ the cab around the short-flow. With the introduction of new FM and FH models at the end of 2001, a redesign of the final assembly was carried out to improve the logistical system and to change the short-flow structure. The first two stations of the short-flow were transferred to newly built pre-flow lines. The work cycles per station in both pre-flow and short-flow were shortened, although even then taking up to 45 minutes per station, and the operators still ‘follow’ the cab through the entire flow. With the redesign the structure of the two departments has also been reorganized. One department is now called pre-assembly department and supplies dashboards, paddle-plates and pre-assembled cabs to the short-flows of the final assembly department.

The logistics department is responsible for all in-going, internal and outgoing logistics of the plant. Most of the employees in this department are responsible for material handling by supplying all processes. Other parts include the shipping department, responsible for the transportation of cabs to Gent and Gothenburg, and the logistics development department, responsible for the design and development of the logistical system of the plant.

The engineering department is a large supporting department, responsible for a variety of tasks. First of all there are a number of sub-departments responsible for the technical support and for the further development of each of the production departments. Most of the employees in the engineering department, however, work with maintenance, which requires for some sections in the process to be operating 24-hours per day. The remaining sub-departments of engineering involve quality, construction and facility services, as well as a special-projects department.

The remaining supporting departments are predominantly administrative. The financial department takes care of controlling, accounting, inventory and invoices. The personnel department consists of the plant’s health-care team, PR and salary administration, besides the usual HR-officers. The latter team is responsible for the full range of Human Resource activities and thus supports and develops management and personnel in all the other departments. Finally, the planning department is a small department responsible for all the plant’s production planning and for fine-tuning production plans with the Volvo sales offices and Umeå’s direct customers: the Volvo production plants in Gent and Gothenburg.

1.5.2 Work Teams at Volvo Umeå

Teamwork has been used for a long time at Volvo Umeå, although none of the experiments in Volvo’s former car-division served as a model until the beginning of the 1990s. During those years all Volvo’s cab-assembly activities were concentrated in the Umeå plant. On the worker-union’s initiative, work teams were formally introduced with an accompanying work organization, rotating team coordinators and a development and incentive program to give every individual operator the opportunity to become fully multi-functional in his or her department. The sociotechnical principle was applied furthest in the newly built assembly area with short-flows, where employees have a high degree of freedom to determine their own pace and working structure.

The introduction of work teams took the usual route (cf. Van Hootegem, Benders, Delarue, & Procter 2005): the “proper organizational structure” was set up and teams were thought to be self-managing. In 1997, however, the plant management was changed and an organization development program (OD-program) was introduced to give teamwork a new impulse by providing a more systematic focus on performance issues. During yearly OD-sessions all teams in the plant had to formulate goals, which were followed-up weekly during team meetings with support of internal OD-consultants. Since then more activities were developed to further structure and institutionalize teamwork, with for example a leadership program and an employee program. Also, step by step, the number of managers was increased from one manager per 4-8 teams to one manager per 2-4 teams.

Generally all teams at Volvo Umeå can be considered as work teams (Cohen & Bailey, 1997), while a further distinction can be made between production teams, present in all production departments, and service teams, present in all supporting departments (Sundstrom, McIntyre, Halfhill, & Richards 2000). Formally, one concept of teamwork exists throughout the plant. In Berggren’s terminology (1993) this is the strong group organization, with a high degree of decentralization, delegation of managerial and support tasks to the team, goal orientation, performance responsibility, and the team’s self-selected group coordinator. Concerning the latter I need to remark that coordinators selected by the team do not exist in the supporting departments, where only formal managers are present. In the production areas this team coordinator is indeed selected by the team in mutual agreement with the team manager. However, in practice the coordinator is not rotating, as intended at the introduction of the work organization in the beginning of the 1990s.

The European and global truck markets appear to be sensitive to economic trends. Together with several important internal reorganizations, such as in the final-assembly by the end of 2001, Volvo Umeå faced radical capacity and personnel changes. In the period between 2000 and 2004 the plant experienced both periods of economic prosperity and declines. As a result hundreds of people have been hired and laid off during a rather limited period. All of these changes are reflected

in the composition of teams, which indeed has not been stable for any team. This truly is a major challenge for team development.

1.6 Overview of Content

This thesis is divided into 5 parts which do not follow the more traditional composition of a dissertation with first theory, then methodology and after that results. Instead, the parts are built around the three research questions that were presented earlier in section 1.4 1.4 of Part I.

Part II relates to the first research question, in which a model for team responsiveness is developed. Chapter 2 outlines the theoretical framework of team responsiveness, after which the data, methods and results are described. Chapter 3 introduces the second research question: the relationship between team responsiveness and results. It provides the theoretical framework and describes the data and methods.

Part III is more of a testing nature. It tests empirically the relationship of team responsiveness with business performance (Chapter 4) and, respectively, with the quality of working life (Chapter 5).

Part IV is a more exploratory one. It elaborates the theoretical framework of team responsibilities (Chapter 6), and it attempts to trace its relationship to team responsiveness guided by a couple of hypotheses (Chapter 7).

Part V contains the final chapter of this thesis. Chapter 8 summarizes the findings of this study, presents the overall model, describes the strengths and weaknesses of the research, and concludes with practical applications for team development.

PART II RESPONSIVENESS: Dimensions of Team

Responsiveness and Their Relations to Team

Responsibilities and Team Results

Chapter 2

Responsiveness: Processes of

Work Teams

In this chapter I will focus on the developmental processes of work teams. As Campion et al. (1993) put it “Process describes the things that go on in the group that influence effectiveness”. I will discuss some of the current approaches for such processes and further elaborate on their most important aspects in working towards a renewed approach.

2.1 Introduction to the Literature

Group dynamics literature includes a number of approaches on group or team development, most of which are phase theories. As can be read in the voluminous work Group Dynamics by Forsyth (1999), most development theories concern the steps that groups go through from the early beginning: individuals come together, form a group, change to an effective group and (possibly) separate again after a certain period of time. A famous example of this is the Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Theory by Schutz (1958; 1992). Most commonly used and cited in group-dynamics literature (Miller 2003) is the group development theory by Tuckman (1965), later extended by Tuckman and Jensen (1977), describing the five stages a group goes through:

Forming. The initial group phase of orientation between group members and testing of interpersonal and task behavior.

Storming. The second stage of the group process in which interpersonal conflicts and positioning are the basis of ‘group influence and task requirements’.

Norming. Overcoming the resistances of the second phase are the inputs for group cohesiveness and developing norms and roles in the third phase.

Performing. This is the fourth stage of group development and focuses on task performance. The roles and group structure developed in norming are the basis for accomplishing the task.

Adjourning. In this final phase the group separates and, in a new form, starts again with forming.

Tuckman (1965) built his theory about the conception of “interpersonal stages of group development” and “task behaviors” on the “contention … that any group, regardless of setting, must address itself to the successful completion of a task. At the same time, and often through the same behaviors, group members will be relating to one another interpersonally”. He based his stages of group development on extensive literature concerning findings in therapy groups, training groups, and natural and laboratory groups.

Despite the popularity of Tuckman’s model, there is also some fundamental criticism on phase theories like Tuckman’s. This criticism is fourfold. The first is that team development often deviates from the sequential steps in phase development (Forsyth 1999). Groups omit certain phases as defined by Tuckman, move through the phases in different orders or develop in ways that cannot be described by Tuckman’s phases (Seeger 1983). The second is that there is no exact demarcation between the phases, because certain group dynamical aspects do not occur timely nor in sequential order (Arrow 1997). Thus, teams in practice do not always develop according to clear distinguishable phases. Third, the theory is based on the temporal patterns of time-limited therapy and laboratory groups, and it is questionable whether these patterns well-describe the processes of work teams. As Cohen and Bailey emphasize: “The findings from studies of undergraduate psychology or business students are much less likely to apply to practicing managers, employees or executives” (Cohen & Baily 1997). Further, many of the studies performed in laboratories do not examine the organizational features external to teams (Cohen & Baily 1997). Fourth, Tuckman’s model tells us little about the relations to the inputs and outputs of the phases. The final phase makes a link to task completion, but this is a rather general description of performance. The model’s main concern remains to be the sequence by which group behavior occurs.

I regard team developmentas the whole of inputs, processes and outputs of work teams. A first model has been depicted in the previous chapter, and in the following sections I will further elaborate the process element of this model, called responsiveness.

I will use the definition of team responsiveness in terms of action and behavior instead of design and conditions. Another important aspect of my definition is that team responsiveness is a process of self-management, which changes over time depending on the (changes of) inputs to teams. It are the development and levels of these self-management processes that eventually lead to better team results. Team responsiveness is the group process of self-management in terms of actions and behavior in relation to given responsibilities (tasks, goals and challenges, desired outcomes).

Following Marks, Mathieu and Zaccaro (2001), I specifically do not refer to team developmental processes as “emergent states: constructs that characterize properties of the team that are typically dynamic in nature and vary as a function of team context, inputs, processes, and outcomes.” Such emergent states “tap qualities of a team that represent member attitudes, values, cognitions, and motivations” (Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro 2001), whereas I am interested in the team’s processes of actions and behavior.

I distinguish several streams in the literature that deals with the subject of developmental processes of teams. These I broadly define as:

1 Consultancy phase models 2 Sociotechnical phase models 3 Recurring phase models 4 Process models

In the following sections I will discuss the important literature for each of these streams. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses. However, all of them provide valuable aspects. I have summarized and used these in my study of Volvo to answer the first research question: How can the team developmental processes be described? Therefore, in the sections after the theoretical discussion I will present the methods and the study’s results that will answer this question.

2.2 Phase Models and Process Models

In this section I will discuss the key literature in each of the distinguished streams of theory. I will start off with the phase models developed within the American consultancy, since these are the contemporary models in practice and some of them belong to the “most commonly cited” and are used by both “full-time practitioners” and “academic practitioners” (Offerman & Spiros 2001). Together with the sociotechnical models, which will be discussed after that, these form the prescriptive streams. Next, I will introduce the basics of the recurring phase models which can be considered as descriptive. Having introduced these three types of phase theories, I shall subsequently discuss their received criticism, to then conclude by presenting the process models as an alternative to phase theories.

2.2.1 Consultancy Phase Models

In the previous section I described some ideas on the development of groups in general. In the 1990’s, however, a huge interest emerged for teamwork in organizations, and with this “fashion” a number of theories on more applied phase models appeared. Two well-known approaches by American gurus are described in this section. Typical of these approaches are their message of best practice. Although clear similarities can be seen with Tuckman’s theory, the here described

approaches by Katzenbach & Smith (1993) and Wellins, Byham and Wilson (1991) pay more attention to team commitment, team goals, team responsibilities and team management as a practical way to reach so-called high-performance in organizations.

Katzenbach & Smith (1993) basically describe a so-called team performance curve (see Figure 2) based on their impressions from management teams, project teams and teams of professionals (like marketing teams, R&D teams, and so forth). In their diagram they relate the horizontal axis, which describes team effectiveness in terms of how well the group or team works together, to the vertical axis, which shows the performance that the team reaches. They start explaining the difference between a working group and a team by saying that the working group is more a combination of individuals relying on the sum of “individual bests”, while there is no clear common purpose or performance goal that demands a joint accountability (Katzenbach & Smith 1993). Teams distinguish themselves from working groups by common tasks, goals and collective accountability, as well as by the necessity to work as a team to perform and reach these goals. Nevertheless, Katzenbach and Smith (1993) differentiate between team types starting with pseudo-teams, which are weaker than working groups because they have no performance focus or performance achievement, and ending with high-performing teams, which are characterized by a deep commitment to mutual growth and success and thus outperform all other teams.

Figure 2 Team performance curve (source: Katzenbach & Smith, 1993) Team performance curve

w orking group pseudo team potential team real team high perform ing team Team Effectiveness Performance Impact

Wellins, Byham & Wilson (1991) focus more on work teams at lower levels in the organization and describe team development as the amount of group empowerment due to increasing levels of job responsibility and authority. They refer to this as the team empowerment continuum and explain how a team in the final level takes care of about 80% of the total possible job responsibilities. They use this maximum of approximately 80%, because they believe that even in the most autonomous organization there will always be leaders who are responsible for a certain share of managing tasks. Later on, Wellins et al. (1991) describe four stages, followed by recommendations on how teams need to be supported and developed in these steps to eventually reach the final level of maximum empowerment. The basics of these development stages show similarities with Tuckman’s stages (1965). In stage 1, getting started, teams are seen as a “diverse collection of individuals”. Team commitment or a feeling of interdependency between the team members is not present yet. Going in circles is what Wellins et al. (1991) call stage 2. The team members start to get a certain team-feeling, and by being more focused on the tasks to be performed, a process of role ambiguity begins. The authors compare the group at this stage with a maturing teenager. The stage also shows similarities with Katzenbach & Smith’s earlier mentioned “pseudo team”, in the sense of a “great letdown” (Wellins, Byham, & Wilson 1991) or “weak performance impact” (Katzenbach & Smith 1993). Stage 3, getting on course, is the phase of concentrating on the goals and dealing with new and crisis situations. Differences in team members, in terms of leadership capacity and expertise, become very clear but are also recognized as helpful for creative processes. In the final stage, full speed ahead, the team focuses on continuous improvement and becoming proactive. In this stage the group can be considered as self-directing and has reached the highest degree of empowerment.

2.2.2 Sociotechnical Phase Models

STS, like the LP approach, does not include specific theories on group behavior or group process (cf. Kuipers, De Witte, & Van der Zwaan 2004). STS is rather to be considered as a design theory, except perhaps for some sociotechnical alternatives like the Democratic Dialogue (Van Eijnatten 1993; Toulmin & Gustavsen 1996). Criticism on the lack of attention for processes in STS comes for instance from Labor Process Theories (Huijgen & Pot 1995). Nevertheless, there are phase models that apply the sociotechnical principles. As an introduction to these phase models I will briefly discuss these principles as identified by Morgan (1993). He calls them “the principles of self-organization and the holographic organization”.

At first Morgan (1993) defines the principle of redundancy of functions, by saying that any system requires some extra space to move. By providing a system with more capacities to act than strictly required for pre-determined actions, it gains in possibilities for self-organization. In a practical sense this means that extra functions are added to a system, like a team; and its members are becoming multi-functional and as a result can replace each other when necessary. The holographic

picture of redundant functions in this case means that any team member reflects the capabilities of the team as a whole.

The second principle of self-organization is that of requisite variety, meaning that any system should be as diverse as the environment in which it acts. This principle is also known as Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety (1958). A control system requires all possible capabilities to act, in order to cope with all possible changes in the environment and survive. The capabilities of a system in a simple and predictable environment, therefore, can be much simpler and less varied than the capabilities of a system in a complex and turbulent environment, where constant new actions are required. The principle of requisite variety also suggests that the redundancy of functions should be positioned there where the action takes place. Minimum critical specification (Morgan 1993), meaning that not everything should be defined into detail, is the third principle. Following this principle creates a large internal flexibility in a system, since many different forms of organizing are possible if only the absolutely necessary aspects of a job are defined. The idea is completely opposite to a bureaucratic design, which tries to control by detailed defined action, thereby removing the opportunities to act flexibly on undefined variances, and, as a result, reducing the possibilities for self-organization.

Morgan (1993) warns how the principle of minimum critical specification can potentially create chaos by its extended possibilities for flexibility and therefore the principle of learning to learn is indispensable. Learning, both single-loop and double-loop, “allow a system to guide itself with reference to a set of coherent values and norms, while questioning whether these norms provide an appropriate basis for guiding behavior” (Morgan 1993). These coherent values and norms are required for giving guidance to the system’s members in situations where little structure is present.

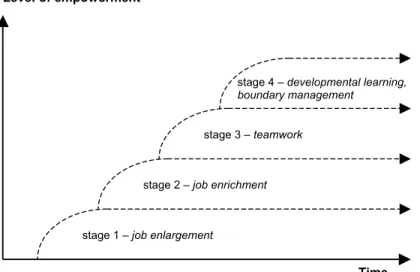

Based on these sociotechnical principles Van Amelsvoort and Scholtes (1994) developed a phase model for work teams (see Figure 3), which is also inspired by Katzenbach and Smith (1993) and Tuckman and Jensen (1977). In every phase, aspects of the sociotechnical concept are involved (Hut & Molleman 1998; Kuipers & De Witte 2005a; Van Amelsvoort & Benders 1996; Van Amelsvoort & Van Amelsvoort 2000):

1 Job enlargement implies the broadening of the types of tasks performed. It increases the job content by focusing on the redundancy of functions and multi-functionality. All members of the team must be able to perform the primary tasks of the team, also identified as ‘technical proficiency’.

2 Job enrichment implies empowering team members by adding more decision-making authority to their tasks, and thereby increasing the team’s

responsibility. The principal characteristic of this phase is “minimal critical specification”. Managers, from production as well as from supporting

departments, delegate some of their responsibilities to the team such as quality and planning activities.

3 Cooperation is described as the ‘self-reliance of the team’. In other words, the teams become ‘socially mature’. The team has to work as a team, and this involves teambuilding, working on communication, and joint decision-making. The team grows in autonomy independent of its supervisor.

4 Continuous improvement. The principles of this phase are ‘double-loop learning’, the capacity to solve most non-routine problems. Put differently, it concerns improving one’s own initiative, and ‘management of team

boundaries’. This latter aspect is based on Katz & Kahn (1978) and has to do with the development of a ‘performance focus’, building relationships with other teams, customers and suppliers.

Figure 3 Sociotechnical phase model (source: Van Amelsvoort & Benders, 1996)

Empirical support for the model by Van Amelsvoort & Benders (1996) is very scarce. The authors mention to have investigated 267 teams by a “quick-scan”, but the items of this scan and the methods of measurement remain unclear. However, they report that 26% of the teams were just established (1996), 63% were in phase two, 8 % entered phase three and none of them reached the fourth phase.

Hut and Molleman (1998) further developed the previous model by integrating it with the theories of Wellins, Byham, & Wilson (1991) and Campion, Medsker & Higgs (1993). Their article presents the outcomes of a small survey measuring these four successive phases. Though the sample was rather small (four teams only), the results are nevertheless interesting. They show that the measured teams cannot be positioned in one single phase at a time. Instead, teams develop in all

Bundling of individuals Group Team Open team Productivity and QWL Time Focus Multi-skilling Team meetings Feedback performance Managerial tasks Analysis of performance Team-building Productivity appraisal Individual appraisal Goal-setting External relations Appraisal of team-leader and support staff

four phases at the same time. Nevertheless, for three of the sampled four teams the first phase had been developed the most, followed by the second, the third and finally the fourth phase; this overlapping pattern of the phases suggests that teams move from “simple to complex” tasks (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 An alternative sociotechnical phase model by Hut & Molleman (1998)

2.2.3 Recurring Phase Models

Criticism regarding Tuckman-like successive phase-theories lead to another perspective on phases of teamwork. Many scholars in this field argue that the developmental process is much more complex than a number of sequential phases. Seeger (1983) notes, for instance, that groups move through phases in different orders or develop in ways that cannot be easily described by Tuckman’s model. Gersick (1988; 1989) studied the development of groups and introduced two main phases, instead of four or five (Tuckman 1965; Tuckman & Jensen 1977). Her punctuated equilibrium model describes an initial phase, which in the mid-point of the group’s time-span undergoes a transition, after which the team comes into a certain action phase to reach its deadlines. Gersick’s model is an accepted alternative to Tuckman’s phase-theory (Miller 2003) and as such has delivered input to other models, such as the recurring phase theory by Marks, Mathieu and Zaccaro (2001). Marks et al. (2001) define team processes as “members’ interdependent acts that convert inputs to outcomes through cognitive, verbal, and behavioral activities directed toward organizing task work to achieve collective goals”. Their much more descriptive approach is based on the “idea that

stage 1 – job enlargement

stage 2 – job enrichment

stage 3 – teamwork

stage 4 – developmental learning, boundary management

Level of empowerment

teams perform in temporal cycles of goal-directed activity, called ‘episodes’” (Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro 2001). They describe ten sub-processes that are part of a transition and action phase, called episodes, and interpersonal processes occurring “throughout both transition and action phases, and typically lay the foundation for the effectiveness of other processes”. These ten sub-processes are divided over the two episodes and the interpersonal process. Transition phase: mission analysis, goal specification, and strategy formulation and planning. Action phase: monitoring progress toward goals, systems monitoring, team monitoring and backup, and coordination. Interpersonal processes: conflict management, motivation and confidence building, and affect management. Both the theories of Gersick (1988; 1989) and Marks et al. (2001) can be labeled as recurring phase theories, with transaction and action taking turns through time for different tasks or sub-tasks.

2.2.4 Critics to Phase Models for Work Teams

In this section I will summarize the criticisms towards the three types of phase models.

Katzenbach & Smith (1993) and Wellins et al. (1991) use the, by origin descriptive, stage approach of Tuckman (1965) as a normative one. Its tools and methods can be very helpful to improve teamwork, but its definition of the phases is rather vague and so is its connection to performance. The approaches give little help to measure the stages of team development and the empirical basis is rather poor.

Stronger defined but also with little empirical basis are the sociotechnical models, such as the one by Van Amelsvoort and Benders (1996). The few empirical studies performed with these models do not support the idea of phases. Hut and Molleman (1998) present the outcomes of a small survey, which shows that teams develop in all four phases at the same time and therefore they suggest a pattern “of complexity in main themes”. A longitudinal study among a larger number of teams showed that even such a pattern could not be discovered (Kuipers & De Witte 2005a). A study of SMWT’s in eleven companies by De Leede and Stoker (1996) also could not find any linear developments as were described by Van Amelsvoort and Scholtes (1994). They conclude that the normative character of phase theories might partly explain this.

De Leede (1997) claims also that Van Amelsvoort and Scholtes (1994) connect structural change, changing and extending the tasks of teams with each phase, with a group dynamical change, going from a group of individuals to a clear distinguishable self-steering team. He wonders if the transitions of the structural change can take place at the exact same time as the transitions of the group dynamical change.

Despite all criticism to these theories, their role in team development practice should not be underestimated. Offerman and Spiros (2001), for example, report that Katzenbach and Smith’s “The Wisdom of Teams” (1993) is the “most

commonly cited” book used by both “full-time practitioners” and “academic practitioners” in the United States.5

More nuanced, more carefully theoretically constructed and to some extent empirically founded, are the recurring phase models. Though interesting and rather promising, there is a problem with these theories for the study of work teams. Both Marks et al. (2001) and Gersick (1989) describe their process models as general for groups or work teams. However, the characteristics they describe seem to be more suitable for groups with a limited, often pre-defined, lifetime, such as project teams, groups of students et cetera.

A superior problem is that the empirical basis of their theories comes mainly from studies carried out among groups of students in laboratories. The nature of such groups is difficult if not impossible to compare to that of work teams (cf. Cohen & Bailey, 1997). Work teams, in production or service, most often do not have a pre-defined lifetime or a clear deadline for a larger task. Instead, they often exist for many years, undergo many changes internally and externally during their life span, have relatively short working cycles and repetitive smaller tasks, and need to deliver a constant stream of products or services.

A clear beginning and end with two phases, as Gersick (1988; 1989) defines, cannot straightforwardly be translated to work teams. Marks, Mathieu and Zaccaro (2001), in that respect, provide a less specific model by introducing the concept of episodes, which constantly recur for each task. This too has a downside for work teams: it is not an easy job to measure every episode for every task or sub-task of an average work team on the shop-floor of a manufacturing site, especially not when these episodes can in turn be broken down into ten processes. This implies that recurring phase theories are theoretically interesting, but less appropriate for real work teams.

Overall, the phase theories lack a clear empirical basis stemming from real work teams and are often poorly defined for scientific use.

2.2.5 Process Models

Although not explicitly labeled as a separate stream of literature, a fourth approach can be distinguished, so-called process models (Stoker & Kuipers 2005). I will discuss two examples of such models that clearly distinguish themselves from the previously introduced phase theories and recurring phase theories. Both are embedded in theory and empirical work in the field of work teams. The major distinction between these process theories and the phase theories is the order of appearance of team process characteristics. Process models claim that the different processes they present are not specifically ordered in phases. Instead,

5

A similar status might have been reached in the Netherlands for the approach developed by Van Amelsvoort.