Author:

Pradeep Kumar Choudhury

Institution: National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA)

Address: 17-B, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi -110016, India. E-mail:

pradeep.hcu@gmail.com Telephone:

+91-9716866068

Title

Patterns and Determinants of Household Expenditure on

Engineering Education in Delhi

Abstract

The present paper examines the patterns and determinants of household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi using the data collected from a student survey from the final year students pursuing B.Tech (both traditional and IT related courses) in various engineering colleges (both government and private un-aided) in Delhi in the academic year 2008-09. The survey has collected data from 1178 students on various aspects as per the requirement of the study and the present chapter uses only the household expenditure data on engineering education and the different factors which determines these expenditures. Hence the data used here is a part of the whole survey. The household expenditure here refers to the expenditure made by the households on tuition fees, other fees, expenditure on housing, food, textbooks, transport etc. Besides these the data is also collected on additional expenditure made by a student on learning English and computer, purchasing cost of computer and cell phones, telephone or cell phone fees, internet fees, entertainment expenses and other necessary life expenses.

The analysis of the data is done in two stages. First, the patterns of household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi is explained with the help of analytical tables on different dimensions like gender of the student (male-female), religion of the student, income of the household, expenditure on different items (fee and non-fee), location of the student (rural-urban) etc. and also the possible cross classification among these factors. Secondly, the determinant of household expenditure on engineering education is estimated with the help of multiple regression analysis which includes both continuous and categorical variables. The effects of various factors will be analyzed separately both for gross and net household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi with the help of different set of independent variables. The net household expenditure is calculated by subtracting the financial supports availed by the students from their gross household expenditure on engineering education.

For the present paper, the various factors determining household expenditure on education is categorized as personal (age, sex); household (annual income of the household, occupation of the parent’s, parent’s education, number of children in the family, religion, caste, etc.); school related (location of the secondary school i.e. either rural or urban, management of the secondary school i.e. either government or

household, medium of instruction in secondary level, board of examination at secondary level, percentage of marks obtained at the secondary level etc. ); institutional (years of coaching, management of the institute/college, discipline of the study in engineering, subsidies/scholarships obtained by the student, educational loans obtained by the student, highest level of education the student plan to attain, quality of the institution etc.).

Key Words: Household Expenditure on Education; Engineering Education; Traditional and IT Related Course; Institutional Factors

Introduction

Funding pattern to education in general and higher education in particular in India has undergone a visible change over the years. Public funding to higher education was the major part of the resource for this sector in early 1960s and very less resource was coming from private sources in terms of fees and other payments from students. But after the implementation of new economic policy in 1990, the trend shifted towards more private funding to higher education. The major private source for fund generation are like running of a number of self financing courses in public universities and establishing self financing colleges and universities itself. While there is the availability of a good and reasonably reliable database on public expenditure on education in India, information on household expenditure is extremely limited. There is hardly any attempt (except few NSSO rounds) to collect the household expenditure data on education on regular basis in India. Hence there is not much research on the extent and determinants of household expenditure on education. But it is increasingly realised that, ignoring household investment proves too costly for educational planning in the long run (Tilak 2002). This problem becomes cumulated when there is a jump from lower level to higher level of education. Because, the lower level of education (elementary) is provided free of cost to all the 6-14 age children of India as a constitutional provision and hence the portion of private expenditure on this level of education is comparatively less. Whereas the higher education sector (including professional education) in India is considered as a quasi-merit good and hence there is a less public investment on this sector (Tilak 1980, 1983, 2008) and the policy is that, the students who want to attain it should pay a substantial part of

the expenditure from the private source. The basic argument behind this idea is that, higher education provides more private benefits (in terms of earnings, prestige etc.) in comparison to social benefits to the nation. The rate of return analysis of different levels of education shows that, the social rate of return from lower level of education is comparatively higher than the higher level of education in India (Kothari 1967, Nalla Gounden 1967, Blaug 1969, Pandit 1973, Tilak 1987)1. This encourages for greater public investment in lower level of education in comparison to higher level. Hence the studies relating to the household investment in the higher level of education assumes a greater significance.

Due to the data constraint there is not enough research/studies on the pattern and determinants of household expenditure on education in India. However, from a quick look through of the meagre studies available on the household expenditure on education (for example, Panchamukhi 1965, Kothari 1966, Shah 1969) clearly shows that a substantial part of the expenditure on education comes from the household sector. Panchamukhi (1965) and Kothari (1966) estimated the total costs of education that included not only public or government costs but also household costs, including opportunity costs of education. Based on a small sample of students in Baroda, Shah (1969) estimated tuition and non-tuition costs incurred by the families on elementary education, by income groups. Similarly in another small sample survey in Andhra Pradesh, Tilak (1987) estimated that household expenditures alone constituted 3.5 per cent of GNP in India in 1979-80. Hence, there is the lack of empirical studies on household expenditure on education, more specifically on determinants of household expenditure on education in India and it is being increasingly felt in a period when public budgets for education in general and higher education in particular are declining and household and private finances are being looked as the substitute of this. The analysis of the patterns and determinants of household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi is a systematic attempt to fill this gap to some extent.

1 None of the studies referred here covers the whole India. Each study has focused to a particular region to

Under this backdrop, the present paper is primarily concerned with the question: What are the various patterns and determinants of household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi? The structure of the paper is as follows: The paper begins with sttaing the problem by providing an overview of the existing literature both from a national and international perspective. Data base and methodology/analytical framework is explained in section II. Section III of the paper explains the patterns of household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi. The effects of various factors i.e. determinants of household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi is examined in section IV of the paper. The paper ends with a brief summary and conclusion of the study.

I. An Overview of the Existing Literature

As mentioned earlier, due to the data constraint there is not enough research/studies on the determinants of household expenditure on education in India. However, from a quick look through of the meagre studies available on the household expenditure on education (for example, Panchamukhi 1965, Kothari 1966, Shah 1969) clearly shows that a substantial part of the expenditure on education comes from the household sector. Panchamukhi (1965) and Kothari (1966) estimated the total costs of education that included not only public or government costs but also household costs, including opportunity costs of education. Based on a small sample of students in Baroda, Shah (1969) estimated tuition and non-tuition costs incurred by the families on elementary education, by income groups. Similarly in another small sample survey in Andhra Pradesh, Tilak (1987) estimated that household expenditures alone constituted 3.5 per cent of GNP in India in 1979-80.

On the whole, research examining the patterns and determinants of household expenditure on education are extremely scanty in India. In fact no single study could be found specifically on higher and engineering education in India, though some studies have focused on the public financing of it2. The non-availability of time series data on household expenditure on education may be an important reason for this. Though the occasional surveys conducted by NSSO and NCAER do provide some important

information on the household expenditure on education, they do not facilitate any systematic comparisons overtime, as they are not collected at a regular time interval. Similarly, the surveys conducted by individual researchers do not allow time series comparisons as they are confined to a particular time, besides being confined to small regions.

The studies related to household expenditure on education both in national and international context revolves around the following:

• There is strong and positive relationship exists between the government and household expenditure on education (Tilak 1991, Acevedo and Salinas 2000) whereas the study of (Strawczynsk and Zeira 2003) in the context of Israel shows an inverse relationship between these two.

• The studies relating to the major determinants of the household expenditure on education shows that income of the household has positive effect on their expenditure on education (Tilak 2000, 2002, Fernandez and Rogerson 2003, Acevedo and Salimas 2000, Hashimoto and Heath 1995, Psacharopoulos 1997, Urwick 2002). However some of the studies have drawn the relationship of family income with the private tuition expenditure rather than taking the aggregate household expenditure on education (Tansel and Bircan 2006, Dang 2007). • Besides household income the other determinants responsible for the household

expenditure on education are religion (Tilak 2002), caste (Tilak 2002), gender (Tilak 2002, 2009, Lakshmanasamy 2006, Panchamukhi 1990), location of the family (Tilak 2009, Panchamukhi 1990), level of education (Tilak 2009), education level of the parents (Tilak 2002, Lakshmanasamy 2006), number of siblings in the family (Tansel and Bircan 2006, Psacharopoulos 1997, Psacharopoulos and Robert 2000, Acevedo and Salimas 2000). However few studies have estimated the influence of all these factors on the quantum of household expenditure on education whereas rests of them have only shown the direction without going for the exact estimation which would have more adherent to the problem.

• The Indian studies which have analyzed the patterns and determinants of household expenditure on education with considering a wide range of variables and also with the use of sophisticated statistical and econometrics tools are mainly based on the data obtained from National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) rounds, National Accounts Statistics (NAS), Central Statistical organization (CSO) (Tilak 1991, 1996, 2000, 2009, Kambhampati 2008) whereas the studies based on primary survey (Lakshmanasamy 2006, Panchamukhi 1990, Salim 1994) have examined the problem in a surface level.

• No studies (except Salim 1994) have analyzed the household expenditure on education by management of the institution and disciplines of the study. All studies cited above have focused on the impact of various socio-economic variables on the household expenditure on education. Though the study of (Salim 1994) has made a comparison of the household expenditure on higher education between engineering and other (arts and science) it has taken a sample of only four colleges from the whole Kerala.

Hence, from the above summary of the review of literature it is clear that, there is the lack of empirical studies on household expenditure on education, more specifically on determinants of household expenditure on education in India and it is being increasingly felt in a period when public budgets for education in general and higher education in particular are declining and household and private finances are being looked as the substitute of this. Hence the analysis of the patterns and determinants of household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi is a systematic attempt to fill this gap to some extent.

II. Data and Methodology/Analytical Framework

The present paper uses the primary data collected from a student survey from the final year (VII Semester) students pursuing B.Tech in various engineering colleges (both government and private) in Delhi. The suvey has collected data on a number aspects as per the requirement of the study and the present paper uses only the the private expenditure data on engineering education and the different factors which determines these expenditure in the academic year 2008-09. Hence the data used here is a part of the whole survey. The household expenditure here refers to the expenditure made by the students on tuition fees, other fees (which include the library fees, examination fees, fees on games and sports) expenditure on housing, food, textbooks, transport etc. Besides these the household expenditure here also includes additional expenditure made by a student on learning english and computer, purchasing cost of computer and cellphones, telephone or cellphone bills, internet bills, entertainment expences and other necessay life expences.

The analysis of all the data mentioned above is done here in two stages. First, the patterns of these expenditures are explained with the help of cross tables by individual characteristics (gender, caste, religion), household characteristics (parent’s occupation, family income, region from which the student belongs) and institutional characteristics (management of the institution) and also the possible cross classification among these factors. Secondly, two household expenditure functions are estimated which includes the regression equation that relate the total household expenditure on engineering education, non-fee expenditure on engineering education to its determinants. The notational expression of the model is as follows:

ln THEE = α + βiXi + µ

Where

ln THEE = logarithm of annual total household expenditure on engineering education, α = intercept term which is interpreted as the average value of the dependent variable when all the explanatory variables are set equal to zero.

βi (i ranges from 1….n) are the regression coefficients to be estimated that measures the

Xi (i ranges from 1….n) is the vector of explanatory variables and µ = error term

Besides this a separate household expenditure function is estimated by taking non-fee expenditure (expenditures on dormitory, food, textbooks and transport) as dependent variable and some important socio-economic factors as independent variables.

The variables (both independent and dependent) used for the analysis are quantitative in nature and some are qualitative and used as dummy or categorical variables. The descriptions of the explanatory and dependent variables used in the analysis are as follows:

Table 1: Definition of Variables Used in the Models

Variable Definition

Explanatory Variables

Individual Characteristics

Gender Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student is male and 0 otherwise.

Caste

SC Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student belongs to Schedule Caste (SC) and 0 otherwise.

ST Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student belongs to Schedule Tribe (ST) and 0 otherwise.

OBC Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student belongs to Other Backward Caste (OBC) and 0 otherwise.

Others (forward caste) Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student belongs to other or forward caste and 0 otherwise (taken as reference category).

Religion

Hindu Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student is Hindu and 0 otherwise.

Muslim Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student is Muslim and 0 otherwise.

Sikh Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student is Sikh and 0 otherwise.

Others Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student is from other religion (Jain, Buddhist, Christian) and 0 otherwise (taken as reference category).

Family_income Continuous variable showing the annual income of the family.

Father occupation

Fatocp_proff Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the father occupation is professional worker and 0 otherwise.

Fatocp_busn Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the father occupation is business and 0 otherwise.

Fatocp_others Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the father occupation is others (occupation other than professional workers and businessman) and 0 otherwise (taken as reference category).

Mother occupation

Motocp_proff Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the mother occupation is professional worker and 0 otherwise.

Motocp_busn Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the mother occupation is business and 0 otherwise.

Motocp_others Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the mother occupation is others. (Occupations other than professional workers and businessman) and 0 otherwise (taken as reference category).

Father_schooling Continuous variable showing the years of schooling of father. Mother_schoolng Continuous variable showing the years of schooling of mother. Sibling Continuous variable showing the number of siblings in the family. Region Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the students belongs to

Delhi or neighbouring states and 0 otherwise.

Famown_house Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student’s family owns a house and 0 otherwise.

School Characteristics

Sec_location Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has studied from an urban secondary school and 0 otherwise.

Sec_mangmt Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has studied from a privately managed secondary school and 0 otherwise.

Sec_medium Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the students has passed the secondary schooling with English medium and 0 otherwise.

Sec_board Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has passed their secondary examination from CBSE & ICSE board and 0 otherwise. Sec_marks Continuous variable showing the percentage of marks obtained by the

students in their secondary examination.

Part-time Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has done part-time job during course and 0 otherwise.

Mngt_pvt Dummy variable which takes the value 1 if the students are from privately managed engineering institutions and 0 otherwise (if students are from government management institutions i.e. either from central government or state government management institution).

Dept_IT Dummy variable which takes the value 1 if the students are from IT related departments and 0 otherwise (if students are from traditional departments).

Scholarship Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has received scholarship from the institution and 0 otherwise.

Edu_loans Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has received educational loan from commercial bank and 0 otherwise.

Further education of the stude nts

Further_edu0 Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has planned to do bachelor degree and 0 otherwise (taken as reference category). Further_edu1 Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has planned to

do master degree and 0 otherwise.

Further_edu2 Dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the student has planned to do doctorate degree and 0 otherwise.

Inst_quality Categorical variable that takes the value of 1 if the institution is poor, 2 if the institution is average, 3 if the institution is good and 4 if it is excellent.

Dependent Variables

Edu_cost Continuous variable showing the total household expenditure on engineering education

.

Nonfee_exp Continuous variable showing the total household expenditure on engineering education excluding tuition and other fees.

III. Patterns of Household Expenditure on Engineering Education in

Delhi

The total household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi consists of tuition and other fees including examination fees; non-fee expenditures (dormitory, food, textbooks and transport) and additional expenditures (English and computer coaching, electronics, internet, cell phone, entertainment and other necessary life expanses). The non-fee expenditures are normally spent by the students to pursue the course whereas the additional expenditures are not necessarily spent by the students. Hence it is an optional expenditure made by the students belongs to middle and higher income group of families. Table 2 below reveals the item wise annual average per student household expenditure, share of each item’s expenditure to total household expenditure and the share to annual family income on engineering education in Delhi. A household spends around Rs. 71 thousand annually for the B.Tech course of theirs wards in Delhi which is 18 per cent of the annual average income of the family. This is comparatively higher than the per student institutional expenditure made by all the engineering institutions except college number 7. However the general impression is that households spend very little on education, including on higher education in India, and that higher education is provided by the government almost free to everybody (Tilak 1993).

The total fees paid by the students on engineering education (B.Tech course) constitute 60 per cent of the total household expenditure, the share being 55 per cent towards tuition fees and around 10 per cent for other fees which constitute of library fees, examination fees, fees on games and sports. Households pay something like 11 per cent of their total income towards fees (10 per cent for tuition fees and 1.7 per cent towards other fees) of their wards pursuing B.Tech in Delhi. The share of other fees paid by the students is only around 16 percent of the total fees paid by the students and the rest 84 percent is paid as tuition fees. Contradictory finding is obtained in a study done among the under graduate students from government, aided and self financing colleges in Tamil Nadu for the year 1994-96. Around 17 per cent of the total household expenditure is spent on tuition fees and 42.47 per cent is spent on other related fees though the sample here includes the

students from different disciplines like arts and science including commerce, engineering, medicine including dental, agriculture, veterinary and law (Lakshmanasamy 2006). The annual average non-fee expenditure (housing, food, textbook and other class material, transport and other) occurred by the engineering students in Delhi is about Rs. 23 thousand which is 32.1 per cent of the total household expenditure and 5.8 per cent of the annual family income. A study conducted on school education with the help of 1994 NCAER household survey data reveals that students studying in government schools spend 70 per cent of their total household expenditure on books and uniforms (Tilak 2002). The major portion of the non-fee expenditure constitute of dormitory and food (roughly 12 thousand for each) and least being on text books and other class materials. Similarly the share of total household expenditure on transport is comparatively less (8.3 per cent), may be due to the hostel facility available in most of the engineering institutions in Delhi.

Annual average amount of additional expenditures made by the students is more or less similar with the annual average expenditure of the students on non-fee expenditures. The highest share of the additional expenditure is occurred in English and computer classes followed by purchasing of electronics items. The share of annual average additional expenditure is 32.6 per cent of total household expenditure and 5.9 per cent of the total annual family income.

Hence the share of household expenditure on different items reveals the expected result; as a major portion of the same is spend on fees followed by additional expenditure and least on non-fee expenditure and it is pertinent to note that expenditures on different items are interrelated, as the coefficient of correlation given in Table A.1 in appendix. The engineering education in Delhi is costlier as a household need to spend 18 per cent of its annual income on its wards to provide a B.Tech degree and in addition 10 per cent on coaching expenditure to perform well in the entrance examination. The financial burden is relaxed only to a smaller extent through financial assistance received by the students. However most of the students (mainly from lower and middle income group) pursuing B.Tech degree go for educational loan either from institutional source (commercial

banks) or from non-institutional source (family and friends) to finance their education and this aspect is analyzed in detail in section 4 of the paper.

Table 2: Item wise Per Student Household Expenditure on Engineering Education in Delhi (Rs.Rs.Rs.Rs. in ’000)

Item of Expenditure Amount % to total Household Expenditure

% to Annual Family Income

Fees

Tuition fees 39.04 55.25 9.99

Other fees (including examination fees) 6.85 9.69 1.75

A. Total fees 42.35 59.93 10.84

-on-fee Expenditures

Drom/Housing 11.98 16.95 3.07

Food 11.84 16.76 3.03

Textbooks and other class materials 3.88 5.49 0.99

Transport 5.88 8.32 1.51

Others 6.31 8.93 1.62

B. Total non-fee expenditures 22.72 32.15 5.82

Additional expenditures

English and computer classes 12.38 17.52 3.17

Electronics (cell phone, computer) 8.96 12.68 2.29

Internet fees 4.35 6.16 1.11

Telephone or cell phone fees 3.51 4.97 0.90

Necessary life expenses 7.96 11.27 2.04

Entrainment expenses 4.28 6.06 1.10

Others 4.85 6.86 1.24

C. Total Additional Expenditure 23.08 32.66 5.91

D. Total Household Expenditures (A+B+C) 70.66 - 18.09 (Rs.Rs.Rs.Rs. 390.60)

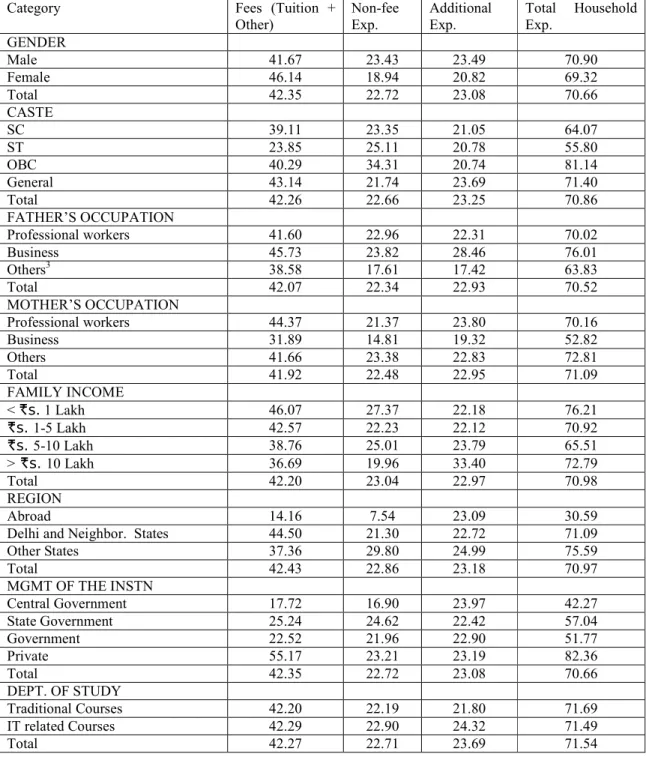

Table 3 below shows the expenditure made by the households on different heads (fees, non-fee items, additional and total household expenditure) on engineering education in Delhi by gender, caste, parents occupation, family income, region from where the student belongs and management of the institutions. Besides these an attempt was also made to present the expenditure details by age of the students and secondary schooling details (location of the secondary school, management and medium of instruction in secondary schools, board of secondary examination, percentage of marks scored in the examination). However the results were not influential (not much difference within the categories) and hence are not reported in table 2 but these are included as explanatory variable in the OLS regression to find out the factors determining household expenditure and the coefficients are presented in the tables 4. It is expected that there exists a difference in the expenditure made by the households on different items due the difference in their socio-economic profiles and the type of institutions they are attending, though the difference may not be expected large in the payment of fees (mainly tuition

fees) as it is decided by the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) for both private government management institutions.

Table 3: Item wise Per Student Household Expenditure on Engineering Education in Delhi by Socio-Economic Profiles of the Students

Category Fees (Tuition +

Other) Non-fee Exp. Additional Exp. Total Household Exp. GENDER Male 41.67 23.43 23.49 70.90 Female 46.14 18.94 20.82 69.32 Total 42.35 22.72 23.08 70.66 CASTE SC 39.11 23.35 21.05 64.07 ST 23.85 25.11 20.78 55.80 OBC 40.29 34.31 20.74 81.14 General 43.14 21.74 23.69 71.40 Total 42.26 22.66 23.25 70.86 FATHER’S OCCUPATION Professional workers 41.60 22.96 22.31 70.02 Business 45.73 23.82 28.46 76.01 Others3 38.58 17.61 17.42 63.83 Total 42.07 22.34 22.93 70.52 MOTHER’S OCCUPATION Professional workers 44.37 21.37 23.80 70.16 Business 31.89 14.81 19.32 52.82 Others 41.66 23.38 22.83 72.81 Total 41.92 22.48 22.95 71.09 FAMILY INCOME < Rs. 1 Lakh 46.07 27.37 22.18 76.21 Rs. 1-5 Lakh 42.57 22.23 22.12 70.92 Rs. 5-10 Lakh 38.76 25.01 23.79 65.51 > Rs. 10 Lakh 36.69 19.96 33.40 72.79 Total 42.20 23.04 22.97 70.98 REGION Abroad 14.16 7.54 23.09 30.59

Delhi and Neighbor. States 44.50 21.30 22.72 71.09

Other States 37.36 29.80 24.99 75.59 Total 42.43 22.86 23.18 70.97 MGMT OF THE INSTN Central Government 17.72 16.90 23.97 42.27 State Government 25.24 24.62 22.42 57.04 Government 22.52 21.96 22.90 51.77 Private 55.17 23.21 23.19 82.36 Total 42.35 22.72 23.08 70.66 DEPT. OF STUDY Traditional Courses 42.20 22.19 21.80 71.69 IT related Courses 42.29 22.90 24.32 71.49 Total 42.27 22.71 23.69 71.54 3

Due to less number of observations in number of occupations (clerical and related workers, service workers, farmers, fishermen and related workers, skilled worker, retired and workers not classified by occupation) they are combined with ‘other category’ for both father and mother.

The annual average household expenditure made by the male students is slightly more than the female students studying in engineering education in Delhi, the amount being Rs. 70.9 thousand and Rs. 69.3 thousand respectively. Similarly in the expenditure of other items like non-fee and additional expenditures there exists a marginal difference between the male and female candidates, the difference being Rs. 4.4 thousand in non-fee items and Rs. 2.67 thousand in additional expenditures. However annual average amount of fees paid by the female students is more than the male students in engineering education in Delhi. Hence the gender difference exists in the household expenditure is against females. The preference for households to invest in the education of male children than that of female children is widely established and the same pattern holds good whether the children are enrolled in government and private engineering institutions. The finding is similar with the study conducted in school education by using NCAER household survey data (Tilak 2002), a study conducted by using 42nd round of NSSO data (Tilak 1996) and also in a study conducted with the help of 52nd round NSSO data (Kambhampati 2008) but contradicts the findings of the study (where female students spend more than the male students) conducted in three states of India namely Maharashtra, Karnataka and Rajasthan (Panchamukhi 1990). The differences in expenditure per student on education by households are largely attributable to parental discrimination against spending on females’ education. However the studies related to returns to education reveals that investment in girls’ education yields higher returns and hence the pattern of household expenditure needs to be changed.

The annual average household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi varies widely across the different social category. The total household expenditure paid by the OBC students is highest (Rs.81 thousands) followed by general category students (Rs. 71 thousand). As expected the lowest amount of household expenditure is done by ST students which is Rs. 55.8 thousand. Similar trend is also followed in the payment of fees by the students from different castes i.e. students from OBC category pay the highest and ST students pay the lowest. However in case of additional expenditure, students from general category spend the highest amount (Rs. 23.6 thousand) in comparison to other

social category students, the difference within the categories being less. There exists a huge gender difference in the household expenditure made by the OBCs than other social category. The male students spent around Rs. 82 thousand whereas the difference between male and female expenditure is only around Rs. 2 thousand for both general and SC category. Similar difference also exists between several religious groups. While Muslim households spend the least on engineering education per student, students from other religion (Christian, Buddhist and Jain) category spend maximum. Expenditure of Hindu and Sikh religions lies in between.

Around Rs. 76 thousand is spent by the students whose father’s are from business category whereas it is Rs. 70 thousand for the professional workers and Rs. 63.8 thousand for other occupation group. However in case of mother’s occupation, highest amount is spent by the students whose mothers are from other occupation category followed by professional workers (Rs. 70 thousand). Among the students from other occupation, least is spent by the retired parents (Rs. 37.3 thousand for father and Rs. 58 thousand for mother). In the other items like fees, non-fee expenditure and additional expenditure, students whose father’s occupation is business spend highest whereas it is lowest whose mother’s are from business occupation. This reveals that students get more money to spend in all the items (whether optional or compulsory) if their fathers are engaged in business than theirs mothers in the same occupation.

The household expenditure made by the students on engineering education is expected be income elastic i.e. the household expenditure increases with the increase in the annual family income. However the result reveals something different i.e. the annual average household spending is highest (Rs. 76.2 thousands) for the students from lowest income group (annual family income of less than Rs. 1 lakh) and lowest (Rs. 65.5 thousand) among upper middle income families (annual family income of Rs. 1-5 lakh). For the first two income groups the annual average expenditure by the household is higher among male candidates in comparison to female students whereas for last two income groups’ females students spend more than the male students. Female students from the top annual family income category (above Rs. 10 lakh) spent the highest among all. The fees paid by the students also vary inversely with the annual family income i.e. higher the

annual income of the family lower is the amount of fees paid by the students for their education. Students from lowest income category spend Rs. 46.1 thousands whereas the figure is Rs. 36.7 thousands for the highest income group. For the income group 1-5 lakh the amount is Rs. 42.6 thousands and Rs. 38.8 thousands for the income category of 5-10 lakh. For all the income categories the amount spend for non-fee items are less than the amount spend for fees. The average annual additional expenditure is directly related with the household income and it ranges from Rs. 22 thousands for the income group of less than Rs. 1 lakh to Rs. 33.4 thousands for the category of above Rs. 10 lakh. For the household in the income range of Rs. 1-5 lakh and Rs. 5-10 lakh female students spend less than the male students on additional items whereas for the highest income group (above Rs. 10 lakh) female students spend twice of male students.

Do education level of the parent’s of the household have any effect on household expenditure on education? Generally it is expected that educated parents value the higher education more and hence spend more on higher education of their children. However the result here reveals the opposite as the primary graduate parent’s spend more than the higher educated parents though the difference the difference in expenditure within levels of education is less.

The state from where the state belongs plays an important role in the amount of expenditure made by the students on engineering education in Delhi. It is expected that students from distance states spends more than the students belonging from Delhi and its neighbouring states like Punjab, Haryana, UP and Himachal Pradesh. Taking this fact into consideration the whole sample is divided into three categories namely ‘Abroad’, ‘Delhi and its neighbouring states’ and ‘other states’ and the new variable is named as ‘region’ and the results are reported accordingly though the information is available by state. This reclassification is done mainly due to the less number of students representation from each state. A household from ‘other states’ spends the highest (Rs. 75.5 thousands) on engineering education in Delhi and the amount is Rs. 71 thousands for the students coming from ‘Delhi and neighbouring states’ and Rs. 30.5 thousands for the abroad category. Among the ‘other states’ category, students from Andaman and Nicobar spends the highest (Rs. 157.8 thousand) and students from Orissa spends least (Rs. 46.4 thousand). Similarly, among the students studying engineering education form

‘Delhi and its neighbouring states’ students from Punjab spends the least (Rs. 68 thousands) and students from Himachal Pradesh sends the maximum (Rs. 94.4 thousands). The study conducted by using the 52nd round of NSSO data reveals that students from Delhi spend maximum (Rs. 2122.5) per annum on education and minimum (Rs. 282.7) by the students from Lakshadweep (Kambhampati 2008: 7). Male students from the category of Delhi and neighbouring states and other states spend more than the female students whereas for the abroad category female students spend more than the male students. The highest is spent by the male students from other state category whereas lowest is spend by the male students from abroad category. The amount of additional expenditure made by the students from other states is Rs. 25 thousands, Rs. 23 thousands for abroad category and Rs. 22.72 thousands for the category of Delhi and neighbouring states. For all the three cases male students spend more than female students.

It is highly expected that the total as well as item wise expenditure on engineering education in Delhi varies widely across the management of the institutions as the fees and other policies differ extensively among them. Student admitted in privately managed engineering institutions in Delhi expected to spend more than the students studying in central government and state government management institutions and the same holds good in the present case. The annual average household expenditure is Rs. 51.7 thousands for government management institutions and Rs. 82.3 thousands for privately managed institutions. Within government institutions, state government managed institutions spends (Rs. 57 thousands) more than the centrally managed institutions (Rs. 51.7 thousands). The highest amount is spent by a male student who is pursuing an engineering degree in a privately managed institutions (Rs. 83.7 thousands) and lowest is spent by a female student in a centrally managed institutions (Rs. 29.5 thousands). There is a wide gap exists in the household spending among the OBC students studying in government and privately managed colleges. OBC students from privately managed colleges spend an amount of Rs. 96.8 thousands where as it is Rs. 57.1 thousands for government management institutions. Similarly the household spending of the students from general category in government and privately managed colleges are Rs. 50 and Rs.

83 thousands respectively. In both the management, SC and ST students spend the lowest in comparison to other category of students.

A substantial difference exists in the total fees paid by the students studying in government management engineering institutions and privately managed institution. The average annual fees paid by a student pursuing B.Tech. in government colleges is Rs. 22.5 thousand whereas it is Rs. 55.2 thousand for privately managed colleges. The gap is mainly due to the existing differences in the tuition fees as the other fees paid by the students is a small portion of the total fees and they are more or less similar in both the cases. Within the government institutions, the amount of fees paid by the students differs between central and state government institutions. However this gap is less than the gap exists between government and privately managed institutions. Though in all the cases total fees paid by the female students is less than the male students, the difference is marginal and the maximum difference exists in case of centrally managed institutions where the annual average fees paid by a male student is Rs. 18.4 thousands and for a female student it is Rs. 10.7 thousands. In case of privately managed institutions the amount of fees paid by the students are Rs. 54.4 thousands, Rs. 82 thousands, Rs. 57 thousands and Rs. 55 thousands for the students of SC, ST, OBC and general category respectively whereas students entering into government management colleges spends Rs. 22.3 thousands, Rs. 20 thousands, Rs. 16 and Rs. 22.9 thousands in the category of SC, ST, OBC and general respectively. The total fee paid by a general candidate in a privately managed engineering institution is more than twice than a general candidate studying in a government institutions and this gap is highest in case of OBCs.

There is no significant difference on the annual average expenditure made by the students on the items like dormitory, food, text books, transport in government and privately managed institutions. The amounts paid by the students are like Rs. 22 thousands and Rs. 23.4 thousands for government and privately managed institutions respectively and the annual average amount spend by a student from a centrally managed institution is Rs. 16.9 thousand and state government managed institution is Rs.24.62 thousand. Spending by male students is Rs. 23.4 thousands and Rs. 18.9 thousands for female students. Lowest spending is done by the female students from centrally managed institution (Rs. 13.6 thousand) and highest by male students from state government managed institution

(Rs. 25 thousand). In case of government management institutions for both SC & ST and OBC students the amount spend on non-fee items are greater than the amount spend on fees.

Average annual additional expenditure made by the students on the items like computer, electronics, internet, cell phone and entertainment is Rs.22.9 thousands for government institutions and Rs. 23.2 thousands for privately managed institutions. Within government institutions there is no much difference between the central government institutions and state government institutions. Highest amount is spent by the male candidates studying in central managed institutions (Rs. 24.7 thousand) and lowest (Rs. 14.3 thousand) by female candidates from the same management.

The household expenditure made by the students studying in different department of study expected to be differentiating (mainly on non-fee and additional expenditure) as the requirement of different instruments differs, though there does not exit much difference in the payment of tuition fees and other fees. However this does not holds good in the present study to a greater extent. The annual average household expenditure for student studying in traditional and IT related departments is more or less equal i.e. around Rs. 71 thousands. Students from Electrical Engineering department and Computer Science Engineering department spend least among the traditional and IT related disciplines respectively. In traditional department male students spend more than the female students where it is opposite in case of It related departments. The amount of expenditure by male students in traditional and IT related departments are Rs. 71.7 thousands and Rs. 71.2 thousands and the expenditure by female students are Rs. 70.7 thousands and Rs. 72.4 thousands respectively. There is no difference in the payment of total fees paid by the students in traditional and IT related departments. Students from both the departments pay Rs. 42.2 thousands as fees. However in case of both the departments’ male students’ pay less fees than the female students. The household expenditure towards non-fee items is more for male students in case of both traditional and IT related departments. Annual average spending of students on additional item is Rs. 21.8 thousands for the traditional departments and Rs. 24.3 thousands for IT related departments. Male students from traditional departments spend less than female students on additional expenditure

whereas the reverse is true in case of IT related departments. The expenditure by male students in traditional and IT related departments are Rs. 21.7 thousands and Rs. 24.7 thousands respectively whereas the spending by female students are Rs. 22.2 thousands and Rs. 22.3 thousands.

The extensive tabulation of the data by gender, caste, parent’s occupation, annual income of the household, region, management, department of study attempted in this section reveals a number of important aspects and provides a key to examine the interplay of these factors in the following section with the help of regression analysis.

IV. Determinants of Household Expenditure on Engineering Education

in Delhi

Table 4 below presents the result of the two OLS regressions by taking the annual total household expenditure and annual non-fee expenditure (housing, food, textbooks, transport etc.) made by the household as dependent variables and individual (gender, caste and religion); household (family income, parent’s occupation, parent’s education, number of siblings in the family, region from which the student belongs, whether the family own house or not); secondary schooling details (secondary school location, management, medium of instruction in secondary school, board of secondary examination and percentage of marks received in secondary examination) and institutional (whether the student do part-time job or not, management of the college, department of study, whether the student receive scholarship or not, whether the student avail educational loan or not, further education the student wants to attain and the quality of the institution) as explanatory variables. Besides presenting the coefficient and standard error of the variables, the model shows the R square and adjusted R square (adjusted with degrees of freedom associated with sum of square) for showing the explanatory power of the model and F value to judge the overall fit of the model.

The household expenditure on engineering education is higher by Rs. 0.05 thousands for Male students than female whereas it is Rs. 0.04 thousands in case of non-fee items in Delhi (similar with the findings of Lakshmanasamy 2006 but contradict with the findings

of Kambhampati 2008). However in both the cases the coefficients are statistically insignificant. Students belonging to SC category spend around Rs. 1600 less on engineering education than the students from general category (supported by Tilak 2002, Kambhampati 2008) whereas the difference in expenditure of the ST and OBCs are statistically not significant. Similarly none of the social category is statistically significant for the household expenditure made by the students on non-fees items. Students from Muslim religion spends less on both total household expenditure and non-fee items by Rs. 0.34 thousands and Rs. 0.66 thousands respectively than the students from other religions (Christians, Buddhist and Jain). Though students from Sikh community spend less on the total household expenditure, they spend more on non-fee items than other religion categories.

Unexpectedly the expenditure on non-fee items is inversely related with the annual income of the family (one unit increase in income reduces the non-fee expenditure by 0.15 percentage points) and the result is statistically significant at 5 per cent level of significance. However the total household expenditure is directly related with the annual income of the family though the degree of influence is less. This clearly indicates that the engineering education is a normal good in Delhi. Parent’s education is also inversely related with the total household expenditure made on engineering education in Delhi. Hence keeping other things constant families in which parent’s are more educated spend less on engineering education in Delhi. Students whose parent’s are professional workers and businessman spend less on total household expenditure than the students whose parent’s are involved in other occupations (contradicts the findings of Lakshmanasamy 2006). However the students whose father’s are engaged in professional and business activities spend more on non-fee heads than the father’s belonging in other occupation categories. It is expected that the total number of dependants in the family reduces the household expenditure made by the students on engineering education in Delhi. But the present analysis does not holds good the same, as the number of siblings in the family is directly related with the non-fee expenditure of the household and it does not influence the total household expenditure at all (similar with the findings of Kambhampati 2008). ‘Region’ plays an important role on the amount of household expenditure made by the students on engineering education in Delhi as the students attending engineering

education from ‘Delhi and neighbouring states’ spend less in both total and non-fee items than the students coming from ‘other states’. This may be because of the less expenditure on housing and transport etc.

The student whose secondary school is from urban region spends more on engineering education in Delhi than the students who have completed their secondary schooling from rural region whereas the other secondary school characteristics are statistically insignificant for both total and non-fee heads of household expenditure. The difference in household expenditure between rural and urban students may be due to the difference in the expenditure on additional items, as the students from rural secondary schooling follow less expenditure habit than the students from urban secondary schooling.

Students from privately managed engineering institutions spend more by 54 per cent on their education than students reading in government management engineering colleges and the result is statically significant at 1 per cent level of significance. This is also confirmed in school sector where household expenditure on primary education are 2-3 times higher in private schools than in government schools (Tilak 1996). Similar finding was obtained in a study using 42nd round of Similarly, students studying in IT related departments spend more on non-fee heads by 19 per cent than the students studying in traditional disciplines of engineering education in Delhi. The total household expenditure on engineering education is more for the students who are receiving scholarship whereas students availing educational loan from commercial banks are positively related with the total household expenditure made on non-fee heads. One unit increase in educational loan increases the household expenditure on non-fee heads by 37 per cent. Students’ going for further education after B.Tech (master degree and Ph.D.) spends more on both total and non-fee heads and the results are statistically significant. It may be due to the additional expenditure made by the students to preparing them accordingly for future degrees. With the increase in the quality of the institutions, the total household expenditure on engineering education increases whereas the expenditure on non-fee heads is inversely related with the quality of the institution. The R square of 0.18 for total household expenditure and 0.11 for the estimation of non-fee expenditure shows that, 18 per cent

and 11 per cent of the total variation in the dependent variable is due to the explanatory variables and other 82 per cent and 89 per cent is due to the error term respectively.

Table 4: Determinants of total household expenditure and non-fee expenditure on engineering education in Delhi

Variable Total household Exp. Non-fee Expenditure

Coeff. S.E. Coeff. S.E.

Individual Characteristics

Gender 0.05 0.08 0.04 0.17

SC -0.16*** 0.10 0.00 0.22

ST 0.08 0.14 0.01 0.31

OBC 0.11 0.12 0.24 0.24

Others (forward caste) Reference

Hindu -0.01 0.11 0.07 0.24 Muslim -0.34*** 0.18 -0.66*** 0.39 Sikh -0.18 0.16 0.59*** 0.37 Others Reference Household Characteristics Lnfamily_income 0.01 0.04 -0.15** 0.08 Fatocp_proff -0.05 0.09 0.25 0.18 Fatocp_busn -0.09 0.10 0.33*** 0.20 Fatocp_other Reference Motocp_proff -0.17** 0.07 -0.07 0.16 Motocp_busn -0.19 0.14 -0.37 0.32 Motocp_other Reference Fath_schooling -0.01 0.02 0.02 0.04 Moth_schooling -0.01 0.01 0.00 0.02 Sibling 0.00 0.03 0.18* 0.07 Region -0.02 0.07 -0.18 0.15 Famown_house 0.12 0.10 0.29 0.21 School Characteristics Sec_location 0.09*** 0.09 -0.18 0.19 Sec_mangmt 0.07 0.07 0.11 0.15 Sec_medium 0.10 0.10 0.24 0.22 Sec_board 0.12 0.12 -0.35 0.23 Sec_marks 0.00 0.00 -0.01 0.01 Institutional Characteristics Parttime -0.01 0.07 -0.14 0.15 Mgmt_private 0.54* 0.07 -0.43 0.15 Dept_study 0.01 0.06 0.19* 0.13 Scholarship -0.12*** 0.08 0.00 0.17 Edu_loan 0.07 0.06 0.37* 0.13 Furtheredu1 0.31* 0.07 0.30** 0.16 Furtheredu2 0.22** 0.10 0.40** 0.21 Furtheredu0 Reference Inst_quality 0.05*** 0.03 -0.04 0.07 Constant 3.45* 0.56 4.20* 1.20 RSquare 0.18 0.11 Adjusted R Square 0.14 0.05 F -Value 5.28* 2.01* Observations 751 477

*significant at 1 per cent level of significance, **significant at 5 per cent level of significance, *** significant at 10 per cent level of significance.

V. Summary and Conclusions

The paper highlights some important dimensions on the size and nature of the household expenditure and their determinants on engineering education in Delhi. Some of the findings of the study fulfil the basic arguments of the established theories and some are contrasting the ideas and few of them provide some new dimensions in relation to household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi.

Based on extensive tabulation of the descriptive statistics few important facts are highlighted on the nature, pattern and amount of household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi and this is supplemented by estimating a household expenditure function to examine its determinants. A household need to spend 18 per cent of its annual income on their wards to provide a B.Tech degree out of which a major portion goes towards fees (60 per cent of the total household expenditure) followed by additional expenditure and least on non-fee expenditure. There is not much difference exists in the total household expenditure made by male and female students. However, the students from government management institutions spend quite less than privately management institutions. There is no significant difference on the annual average expenditure made by the students on the items like dormitory, food, text books, transport in government and privately managed institutions. For the first two income groups the annual average expenditure by the household is higher among male candidates in comparison to female students whereas for last two income groups’ females students spend more than the male students. Annual average amount of additional expenditures made by the students is more or less similar with the annual average expenditure of the students on non-fee expenditures.

The determinants of annual average amount of household expenditure and non-fee expenditure estimated with the help OLS reveals that the expenditure on non-fee items is inversely related with the annual income of the family. However the total household expenditure is directly related with the annual income of the family though the degree of influence is less. The number of siblings in the family is directly related with the non-fee expenditure of the household and it does not influence the total household expenditure at

all. The students attending engineering education from ‘Delhi and neighbouring states’ spent less in both total and non-fee items than the students coming from ‘other states’. This may be because of the less expenditure on housing and transport etc. Students from privately managed engineering institutions spend more on their education than students reading in government management engineering colleges. Similarly, students studying in IT related departments are more likely to spend on non-fee items than the students studying in traditional disciplines of engineering education in Delhi. Hence the paper gives a clear cut picture on the household expenditure on engineering education in Delhi by relating it with many socio-economic and institutional aspects and the findings of the study can be used in the financing aspects of enginering education in Delhi and India to some extent.

Appendix

Table A.1: Descriptive statistics of the variables used in different models (Rs. in ’000 mentioned otherwise)

Variable N Mean Std. Dev. Minimum Maximum

Education_cost 915 70.66 43.68 31 300

Lnedncost 915 4.03 0.79 3.43 5.70

Tot_nonfeee_exp. 489 48.18 40.08 1.5 241

Lntot_nonfee 488 3.50 0.96 0.40 5.48

Lnfaminc 1043 12.58 0.82 10.82 14.22 Fath_schooling 1104 14.645 1.892 0 16 Moth_schooling 1070 13.426 3.091 0 16 Sibling 1178 1.486 0.926 0 5 Sec_marks 1178 77.577 9.225 45 99 SC 1178 0.100 - 0 1 ST 1178 0.053 - 0 1 OBC 1178 0.070 - 0 1 General 1178 0.778 - 0 1 Hindu 1178 0.815 - 0 1 Muslim 1178 0.053 - 0 1 Sikh 1178 0.067 - 0 1 Others 1178 0.065 - 0 1 Fathoccu_proff 1178 0.626 - 0 1 Fathoccu_busin 1178 0.224 - 0 1 Fathoccu_other 1178 0.150 - 0 1 Mothoccu_proff 1178 0.234 - 0 1 Mothoccu_busin 1178 0.039 - 0 1 Mothoccu_other 1178 0.727 - 0 1 Region 1178 0.770 - 0 1 Own_house 1060 0.923 - 0 1 Own_land 826 0.654 - 0 1 Sec_location 1178 0.865 - 0 1 Sec_mngmt 1178 0.643 - 0 1 Sec_med 1178 0.853 - 0 1 Sec_board 1178 0.903 - 0 1 Private 1178 0.593 - 0 1 Dept_study 1178 0.761 - 0 1 Parttime 1178 0.223 - 0 1 Furtheredu0 1178 0.260 - 0 1 Furtheredu1 1178 0.610 - 0 1 Furtheredu2 1178 0.130 - 0 1 Inst_quality 1178 2.636 - 1 4 Joboffer 1178 0.360 - 0 1

Note: For the binary variables, mean implies proportion and we do not report the standard deviation.

Table: A.2: Correlation Table: Total fees, total other cost, total additional expenditure, total household expenditure, against the possible factors that may influence these.

* Significant at 5 per cent level of significance

References

Lntotfees Lntotother Lntotaddnal Lnedncost

Lntotfees 1 Lntotother 0.067 1 Lntotaddnal 0.060 0.251* 1 Lnedncost 0.670* 0.501* 0.515* 1 Lnnetedncost 0.621* 0.461* 0.508* 0.950* Scholarship -0.187* 0.024 0.017 -0.109* Ednloan -0.023 0.131* 0.120* 0.033 Gender -0.055 0.075 0.034 -0.004 Hindu 0.184* -0.019 -0.021 0.106* Muslim -0.364* -0.038 0.015 -0.187* Sikh 0.076* 0.065 -0.012 -0.013 Others -0.032 0.008 0.033 0.017 SC -0.062 0.025 0.005 -0.056 ST -0.112* 0.029 -0.037 -0.047 OBC 0.033 0.076 0.015 0.051 General 0.082* -0.083* 0.004 0.033 Lnfaminc -0.105* -0.064 0.084* -0.031 Fathoccu_Proff -0.018 0.048 0.000 -0.020 Fathoccu_Busin 0.131* 0.014 0.072 0.072* Fathoccu_Other -0.131* -0.079 -0.084* -0.060 Mothoccu_Proff 0.032 -0.037 0.032 -0.041 Mothoccu_Busin -0.140* -0.063 -0.047 -0.077* Mothoccu_Other 0.032 0.064 -0.010 0.073* Fath_Schooling 0.011 0.001 0.044 -0.007 Moth_Schooling 0.029 -0.046 0.042 -0.009 Sibling -0.052 0.117* -0.044 -0.041 Region 0.246* -0.086* 0.009 0.068* Famown_House 0.010 0.056 0.034 0.040 Sec_Location 0.071* -0.044 -0.040 0.007 Sec_Mngmt 0.063 0.008 0.037 0.068* Sec_Med 0.163* 0.003 0.005 0.060 Sec_Board 0.257* -0.091* -0.062 0.071* Sec_Marks -0.107* -0.018 0.065 -0.025 Parttime -0.021 -0.035 0.075 -0.026 Furtheredu0 -0.105* -0.063 -0.093* -0.156* Furtheredu1 0.167* 0.027 0.097* 0.171* Furtheredu2 -0.109* 0.036 -0.025 -0.051 Private 0.752* -0.104* 0.030 0.347* Dept_Study -0.028 0.027 0.030 -0.055 Inst_Quality -0.117* -0.004 -0.013 -0.026

Acevedo, G.L. and Salinas Angel 2000. “Marginal Willingness to Pay for Education and the Determinants of Enrolment in Mexico,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2405: 1-22.

Becker, G.S. 1974. Human Capital, New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Blaug, M. 1966. “An Economic Interpretation of the Private Demand for Education.” Economica, 33(130): 166-183.

Blaug and et al. 1969. “The Causes of Graduate Unemployment in India,” Allen Lane, the Penguin Press, London.

Blaug, M. 1970. An Introduction to Economics of Education, Chapter-6 (Cost-Benefit Analysis: The Private calculus), Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, London.

Chakrabarti, A. and Joglekar R. 2006. “Determinants of expenditure on Education: An Empirical Analysis Using State Level Data,” Economic and Political Weekly, 41(15): 1465-1472.

Chowdhury, S. Bose, P. 2004. “Expenditure on Education in India: A Short Note,” Social Scientist, 32 (7/8): 85-89.

Dang, Hai-Anh. 2007. “The Determinants and impact of private tutoring classes in Vietnam,” Economics of Education Review, 26 (6): 683-698.

Fernandez and Rogerson, R. 2003. “The Determinants of Public Education Expenditures: Longer-Run Evidence from the States,” Journal of Education Finance, 27 (summer): 567-584.

Hashimoto, K. & Heath, J.A. 1995. “Income Elasticites of Educational Expenditure by Income Class: The case of Japanese Households,” Economics of Education Review, 14 (1): 63-71.

Husain, I.Z. 1967. “Returns to Education in India: An Estimate,” in ‘Education as Investment,’ edited by Baljit Singh, Meenakhi Prakashan, Meerut.

Johnstone, D.B. 2003. “Cost Sharing in Higher Education: Tuition, Financial Assistance, and Accessibility in a Comparative Perspective,” Sociological Review, 39 (3): 351-374.

Kambhampati Uma S. 2008. “Does household expenditure on education in India depend upon the returns to education?” Working Paper No. 60, Henley Business School, The University of Reading, U.K. Kanellopoulos C. and Psacharopoulos G. 1997. “Private education expenditure in a ‘free education’

country: The case of Greece,” International Journal of Educational Development, 17 (1): 73-81. Kothari, V.S. 1966. Investment in Human Resources, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, for the Indian

Economic Association.

Kothari, V.S. 1967. “Returns to education in India” in ‘Education as Investment,’ edited by Baljit Singh, Meenakhi Prakashan, Meerut.

Lakshmanasamy, T. 2006. “Demand for Higher Education and Willingness to Pay: An Econometric Analysis using Contingent Valuation Method,” Manpower Journal, XLI (4): 97-120.

Lleras, M.P. 2004. Investing in Human Capital: A Capital Markets Approach to Student Funding, Cambridge University press, U.K.

Mehrotra, S. and Delaminica, E. 1998. “Household Costs and Public Expenditure on Primary Education in Five Low Income Countries: A Comparative Analysis,” International Journal of Educational Development, 18 (1): 41- 61.

Nalla Gounden, A.M. 1967. “Investment in Education in India,” The Journal of Human Resources, 2(3). Panchamukhi, P.R. 1965. “Educational capital in India,” Indian Economic Journal, (12) (3): 307-314. Panchamukhi, P.R. 1990. “Private Expenditure on Education in India: An Empirical Study,” (Unpublished

report), Indian Institute of Education, Pune.

Pandit H.N. 1972. “Effectiveness and Financing of Investment in Education in India 1950-51 to 1965-66,” Delhi: Delhi University (Ph.D. Thesis).

Pandit, H.N. 1973. “Cost Benefit Analysis of Indian Education,” a paper presented at the Seminar on Higher Education and Development organized by the Association of Indian Universities, 23-25 March. Prakash, S. & Chowdhury S. 1990. “Determinants of Education Expenditure in India,” Journal of

Educational Planning and Administration, 4 (4): 1-30.

Psacharopoulos and et al. 1997. “Private Education in a Poor Country: The case of Urban Bolivia,”

Economics of Education Review, 16 (4): 395-406.

Psacharopoulos, G. and Mattson Robert. 2000. “Family Size, Education Expenditure and Attainment in a Poor Country.” Journal of Educational Planning and Administration, 14 (2): 169-186.

Psacharopoulos, G. & Papakonstantinou. 2005. “The real university cost in a “free” higher education country,” Economics of Education Review, 24 (1): 103-108.

Roy, A. and et al. 2000. “Educational Expenditure of Large States: A Normative View,” Economic and Political Weekly, 35(17): 1465-1469.

Salim, A.A. 1994. “Cost of Higher Education in Kerala: A Case Study,” Journal of Educational Planning and Administration, 8 (4): 417-430.

Schultz, T.W. 1961. “Investment in Human Capital,” The American Economic Review, (51) (1): 1-17. Strawczynsk M. and Zeira J. 2003. “What Determines Education Expenditure in Israel?”Israel Economic

Review, 1 (1): 1-24.

Tan Jee-Pang. 1985. “Private direct cost of secondary schooling in Tanzania,” International Journal of Educational Development, 5 (1): 1-10.

Tansel, A. & Bircan F. 2006. “Demand for education in Turkey: A Tobit analysis of private tutoring expenditures.” Economics of Education Review, 25 (3): 303-313.

Tilak, J.B.G. 1980. “Allocation of Resources to Education in India,” Eastern Economist, 75 (9): 530-542. Tilak, J.B.G. 1983. “On Allocating plan Resources to Education in India,” Margin, 14 (4): 93-102. Tilak, J.B.G. 1987a. The Economics of Inequality in Education. Sage Publications, New Delhi.

Tilak, J.B.G. 1988. “Cost of Education in India,” International Journal of Educational Development, 8 (1): 25-42.