Do I know you?

Modelling the release from proximity in order to study key

human sociality in the evolution of the European Palaeolithic

Do I know you?

Modelling the release from proximity in order to study key

human sociality in the evolution of the European Palaeolithic

lithic assemblage

Author : Martijn Wezenbeek Student number: s1503405

Course/course code: Thesis BA3/1043SCR1Y-17-18ARCH

Main supervisor: prof.dr. R.H.A. Corbey Co-supervisor: S.T. Hussain MA

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements...4

1. Introduction...6

1.1 The social brain hypothesis and its reliance on archaeology...6

1.2 Problems in Palaeolithic social archaeology and Gamble’s solution...6

1.3 Research objective...7

1.4 Thesis outline, methods and limitations...8

2. A critical treatment of the theoretical framework for the release from proximity...10

2.1 The release from proximity and complicated interaction...10

2.2 A network model (updated)...12

2.3 A theoretical Palaeolithic framework...16

α: Locale...17

β: Region...19

γ: Rhythms...21

2.4. Spatial and Technological correlates...22

2.5 A critical footnote: the cognitive implications of RfP...30

3. The release from proximity as a hypothetical model...34

3.1 Ordering and simplifying technological correlates of RfP...34

3.2 An extended and simplified model of RfP in the lithic assemblage...35

4. Conclusion...42

Abstract...44

List of References...45

List of Figures...47

Acknowledgements

“Only three things matter in a Bachelor thesis. First, focus. Second, focus. Can you guess the third?”

“Focus...?” “Correct.”

True words were spoken thus by Professor Corbey, attempting to reassure that I would not stray from my path and delve too deep into ambitions far beyond my grasp. Admittedly, I have often remembered myself repeating these words, not only during the writing of this archaeological thesis, but also for the one I had to write for philosophy. It has taken some time, and indeed, a few presentations before I was even able to delineate a subject that would not exceed the limits set forth by a common Bachelor thesis. On multiple occasions, prof. Corbey reminded me that my suggestions were a bit too broad in scope, perhaps more appropriate for one or two PhD-theses. He sparked and deepened my interest in the relation between archaeology and philosophy, a relation that is unfortunately not often made by both philosophical and archaeological academics, and one that I was beforehand seeking rather helplessly. This is a developed personal and professional interest that I am sure will have some lasting effect when I continue studying. The most appreciated walks (and occasional interruptions of spotting birds) were always valuable and bore ample opportunity to discuss details of the thesis and, if necessary, give honest criticism and feedback. Personally, I have experienced it as an honour to write a Bachelor thesis under the supervision of prof. Corbey. Even if I end up having delivered a thesis that could not live up to the standards imposed by the professor, I have nonetheless learned to value high academic standards and I can only promise to carry these further in the future.

1. Introduction

1.1 The social brain hypothesis and its reliance on archaeology

The social brain hypothesis proposes a specific hypothesis for explaining the unusually large brains for body size in primates compared to other vertebrates (Dunbar 2009, 562). It is thought that what is extraordinary for primates is a quantitative relationship between brain size and social group size (Dunbar 2009, 562). Importantly, it is assumed that cognitive demands will be much higher (and therefore more costly) when group sizes grow. In turn, the traits that favour higher cognitive costs are selected for, thus increasing brain size steadily over time (Dunbar 2009, 569). The specific evolutionary selection pressure for increasing brain growth, therefore, involves ‘the need to create large coherent social groups that involve a proportionately large number of relationships’ (Gamble et al. 2014, 55). If we apply this evolutionary model of brain growth to Homo sapiens, the prime question is not merely: how did the human brain become so big?; rather, it becomes: how did the social environment affect the growth of the human brain size through human evolution? In light of this hypothesis, however, it becomes clear that if it is to be scientifically valid, some kind of evidence must underpin it. We need to extract social information from prehistoric archaeology in order to establish whether or not an evolutionary push towards becoming more social, i.e. being able to have more, complex relations over time happened (Gamble et al. 2014, 85). In effect, a social archaeology of the Palaeolithic becomes essential in answering these questions.

1.2 Problems in Palaeolithic social archaeology and Gamble’s solution

structures as societies. This meant implementing a so-called top-down approach to early prehistoric social relations. However, as Gamble indicates, this was a notoriously unreliable method, as finding indicators for such social structures could never be directly pointed out due to the sparse differences in material that it could be identified with. After all, one cannot distil social hierarchy and the sort when confronted with a restricted dataset.

The release from proximity (abbreviated: RfP) is one of the main ways of studying social life in the Palaeolithic, particularly as a bottom-up approach that emphasizes the hominin capability to make life complicated, rather than complex (Gamble 1998, 443). In short, the release from proximity encapsulates the social capacity to “carry on a social life as if others are present when they are not” (Gamble et al. 2014, 78). This ‘going beyond’ is considered to be a human hallmark (Gamble 1998, 431). It attempts to signify social interaction as constituted by engaging, creative individuals, who have an agency in shaping their societies, rather than being dictated by certain pre-existing overarching structures. Interestingly, the release from proximity is a social phenomenon that, as we will see, is not reliant on anatomical data like the social brain hypothesis, but can be inferred from the lithic record of the Palaeolithic. If we assess whether or not this theoretical model is viable for studying hominin social behaviour throughout prehistory, we can value its interpretative usefulness in examining human sociality in prehistory, as well as assessing how it might complement the study of the social brain hypothesis.

1.3 Research objective

- How can we make a model with which the release from proximity can be shown to be reflected in the evolution of lithic technology in the European Palaeolithic?

In order to answer this question, the following specific questions have to be raised and answered.

- In regards to the release from proximity in general:

o What is the concept of ‘release from proximity’?

Is it a social phenomenon or a cognitive capacity? o What are its archaeological correlates?

In regards to the release from proximity as reflected in lithic technology

o How can the release from proximity be made fruitful to study the

organization of lithic technology?

o What are its technological correlates (i.e. which phenomena in specific are necessary for studying the release from proximity in lithic technology)?

In regards to assessing its practical viability

o Can we find the technological correlates in actual existing datasets?

To answer these questions structurally, we will turn to the thesis outline.

In the second chapter the theoretical groundwork will be done and I will focus specifically on a) giving a proper definition of the release from proximity, b) discussing how network theory relates to studying RfP, c) integrating this concept in Gamble’s theoretical framework for studying Palaeolithic society and d) specifying the correlates of the release from proximity with lithic technology. Additionally, I will e) discuss some issues in relation to the cognitive aspects that I believe arise from the release from proximity as a social concept. The third chapter will focus on establishing a model that can put forward and test hypotheses with regard to complicated social life and the release from proximity.

For most of the theoretical work, I will make an exegesis of Gamble’s key article and book in relation to the release from proximity, respectively “The Palaeolithic society and RfP: A network approach to intimate relations” (1998) and “Palaeolithic Societies of Europe” (1999). The particular focus will be on reconstructing the theoretical framework, as well as identifying the spatial and technological correlates for RfP. With regard to network theory and the cognitive implications of RfP, I will contrast this older approach to Gamble’s more recent approach of studying the social brain. Finally, in modelling RfP as a test-based model, I will mostly do so by inferring the most important bits and putting them in a hierarchical model.

2. A critical treatment of the theoretical framework for

the release from proximity

2.1 The release from proximity and complicated interaction

As already stated in the introductory chapter 1.2, Gamble sought to establish a bottom-up approach with which to study Palaeolithic societies. Following primatologists who studied ape societies bottom-up, meaning that society was taken to be created by the individual’s actions and performances (Gamble 1998, 429). His reorientation of the focus from society as a pre-structural being to it being the result of individual creativity raised two questions:

1) How can individuals socially act beyond direct face-to-face interaction?

2) How do societies function as performed societies?

a human hallmark.1 (Rodseth et al. 1991, 239; Gamble 1998, 431; Quiatt and

Reynolds 1993, 141) Simply put, if it is true that the release from proximity is a particularly human trait, primates do not have that trait. Thus, if the trait is one of social cognition (having emerged by means of evolutionary pressure), it must necessarily have emerged after the occurrence of the last common ancestor of human and apes, and must be located in hominin evolution. On the question of how the release from proximity is mediated and how it is expressed in the archaeological record, we will focus more deeply on in subchapters 2.2 and 2.4 respectively.

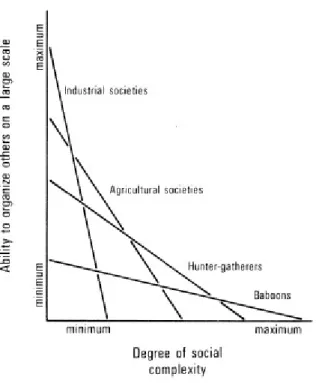

Question 2) emerges as the intensity of social interaction is addressed. Non-human primate society, for example, is recognized as socially complex, whereas human society is described as being socially complicated. Specifically, the difference in intensity of social interaction between humans and other primates comes about by differences in “[…] the practical means that actors have to enforce their version of society or to organize others on a larger scale, thereby putting into practice their own individual society is.”2 (Strum and Latour 1987,

790, author’s italics). Non-human primates are in this regard much more limited to the use of their body as a resource to ‘enforce their version of society’. Complex sociality is the result of negotiating more than one social factor at the same time (age, gender, kinship etc.). Conversely, complicated sociality is based on the definition of complicated as “something (…) when it is made of a succession of simple operations” (Strum and Latour 1987, 790). Here, additional extra-somatic material and symbolic resources make up the means by which social relations can be negotiated, not only between individuals but also between higher units of a collective of individuals (e.g. states, organizations, companies) (Strum and Latour 1987, 793). As a result of complication, social tasks become

1 See Corbey (2000, specifically 164-166) for a discussion of the release from proximity as a trait

fundamentally double focussed on being and becoming human, as something closely related to Scheler’s notion of Weltoffenheit (the ability to “distance from and control over one’s own impulses, thus getting access to one’s environment more fully”) as contrasted to the ape’s

Umweltbahn (being in an environment laden with biologically relevant meanings to which the individual quasi-automatically reacts).

2 I feel the need to express one particular concern here with regard to the implied cognitive

less complex as their dimensions become reduced to particular domains, instead of being focused on a set of social factors in one task: “By holding a variety of factors constant and sequentially negotiating one variable at a time, a stable complicated structure is created.” (Strum and Latour 1987, 792-3)”.

Figure 2.1: complexity versus complication: the trade-off (Strum and Latour, 792).

Gamble enhances this conception of the increasing complication of social life by introducing the process of amplifying aspects of social life. Amplification is the process of boosting existing signals of emotions or the mood, either by physical action or through ‘feelings for objects’. Materials can in this regard be interpreted as reducing the time necessary for performing socially by amplifying the core resources (those that relate to the senses and basic needs, such as music-making or distinguished cuisine) (Gamble 2014, 70). Increased social complexity through amplification is possible because although there is less time spent on social performance, amplification nonetheless enhances the intensity of related emotions that are paired with social actions, either occurring through the bodily action or through material interaction.

Network analysis is a crucial part of analysing the possibility for a release from proximity. It provides a framework in which social concepts based on interaction and negotiation by individuals is formalized (see table 2.1 for an updated model) (Gamble 1999, 42). In his “Palaeolithic societies of Europe”, as well as in his paper “the release from proximity”, Gamble introduces a network model that we will shortly touch upon. Gamble’s own assessment of group size reconstruction and its relation to RfP will be discussed in an eclectic, but chronological manner. We will look at how the model was revised in several aspects and finally was associated with a model for reconstructing group sizes in past species.

Taking on social network theory, Gamble establishes a categorization of an individual-centred network, marking each level by a different gradation of intimacy (Gamble 1998, 432). What is of key interest here is that different kinds of resources play a key role in establishing and/or maintaining interactions in each layer of the network. For example, interacting with someone in the intimate network requires emotional resources in order to ‘create the high density affective ties among close kin and friends’ (Gamble 1998, 432). Gamble argues that material and symbolic resources primarily reduce the time spent to interact with individuals. Affection and emotional resources reduce in the higher more ‘abstract’ gradation of networks. All the networks mentioned use all types of resources to some extend in contemporary human societies (Gamble 1998, 433).

Generally, the following can be stated of all individual networks. The intimate network depicts high-intensity mostly permanent and stable multiplex

assist an ego emotionally and materially during daily routines (Gamble 1998, 434). The extended network consists of acquaintances and friend-of-friends; transitive ties are established in this network, meaning that relationships are created between non-interacting individuals through an ‘intermediator’: a person B, who links person A to person C (Gamble 1998, 435). The intimate, effective and extended networks together make the personal network. Finally, the global network represents the category of ‘otherness’ and the ‘opportunities for new ties to be brought into the personal network’ (Gamble 1998, 436). The last category is potentially unbounded. Each network is ascribed a number of people that represents the average size of that network. In “Origins and Revolutions”, Gamble makes the table slightly more sophisticated, by adding sample descriptions of modal sizes and making more clear the range of individuals constituting the group size of each.

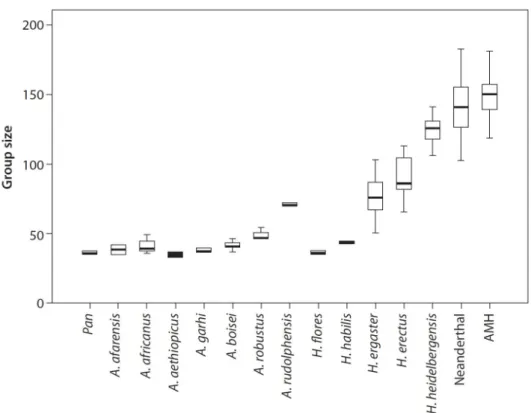

However, recently Gamble has revised this model in a few ways. A study by Roberts revises some of the main concepts of the rather rudimentary network overview provided by Gamble. Firstly, the newly proposed personal network model is an ‘inclusive hierarchical structure’, meaning that each ‘higher’, or more intimate network is and its attributes, including the number of individuals it consists of is included in every lower level network (see figure 2.2). The networks are also rebranded. From most to least intimate it consists of the support clique, the sympathy group, the band and the active network and even more layers beyond that. Gamble himself seems to rebrand it as ‘close kin’, ‘intimates’, ‘support groups’, and ‘diverse networks which an individual can call on either to find food or for protection’ (Gamble 2014, 69). Moreover, the average number of maximum connections with alters in each new network-layer is multiplied by three, reducing some of the numbers proposed in the earlier division of networks (Zhou et al. 2005); this is called the ‘rule of 3’ (Gamble et al. 2014, 42).

postulated for extinct species. If the capacity of the cranium can be measured fairly accurately, and on the basis of that a brain size can be reconstructed, a maximum number of individuals can be estimated as the group size limit. I have to note here that this does not imply that figure 2.3 is able to indicate actual group sizes in past non-human populations; it merely points out what was hypothetically the limit for individuals belonging to certain species to interact socially without overreaching the cognitive load involved. Moreover, figure 2.3 has in itself little value insofar as it can be used to point out when RfP came into existence since brain size is not further defined in particular cognitive capacities.

In this thesis, I will argue that this predictor is not accurate with regard to assessing the lithic assemblage, mainly because the model I will propose will not be readily concerned with cognitive capacities, but rather with social behaviour. Although community size might be predicted by brain capacity, RfP cannot be

readily assumed to have existed unless it is materially established. What I will argue for however is that brain size can indicate when there was definitely no RfP, namely if the associated community sizes strongly suggest it was impossible to reach far beyond social life. For the purposes of this thesis, I will stick more closely to the network model proposed by Gamble in table 2.1, rather than to his later revisions.

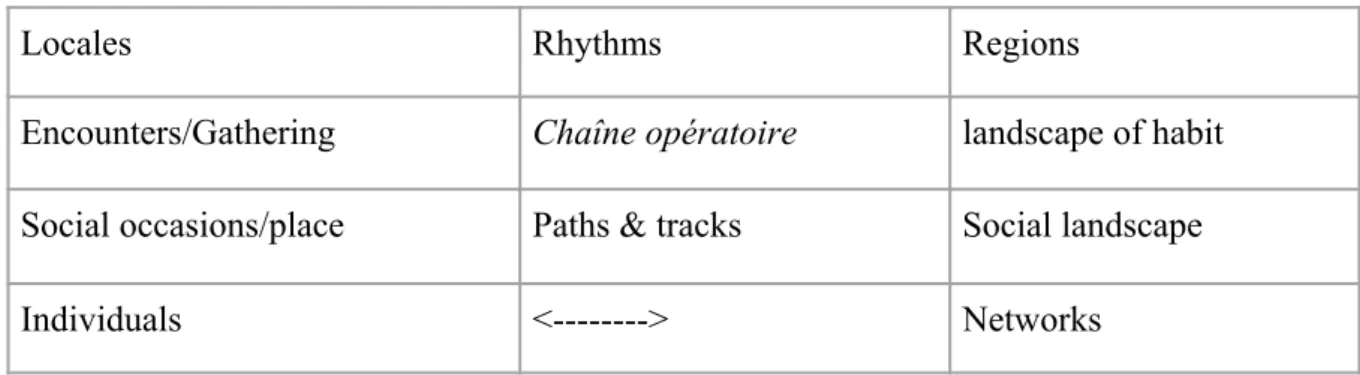

2.3 A theoretical Palaeolithic framework

The proposed theoretical framework for studying Palaeolithic societies is shown in Table 2.2. According to Gamble, there are two levels of analysis: locales and regions. Both are linked by the rhythms of social technology. The strong spatial emphasis reflects the contexts of interaction and the construction of social networks by individuals (Gamble 1999, 65). These are spanned by a series of closely linked concepts, which are jointly referred to as rhythms They provide us

with the conceptual link between the dynamics of past action and the inert residues of those actions. It can only be inferred from artefacts. It links the actions to the region, the individual to a wider social structure. A brief introduction to each concept will be provided, with a subsequent discussion on the possible artefactual candidates that can be studied through this framework.

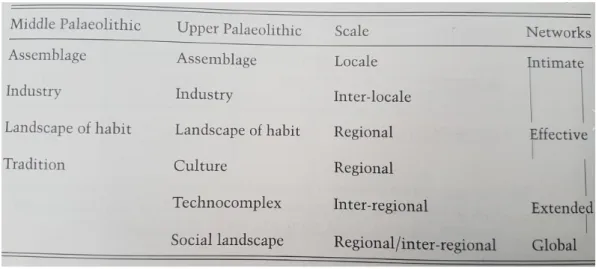

Table 2.2: A framework for studying Palaeolithic society (after Gamble 1999, 65)

Locales Rhythms Regions

Encounters/Gathering Chaîne opératoire landscape of habit

Social occasions/place Paths & tracks Social landscape

Individuals <---> Networks

There are two levels of analysis, locales and regions, which are linked by the rhythms of social technology. The strong spatial emphasis reflects the contexts of interaction and the construction of social networks by individuals. (Gamble 1999, 65) These spatial dimensions are spanned by a series of closely linked concepts, which are jointly referred to as rhythms. Rhythms provide the conceptual link between the dynamics of past action and the inert residues of those actions. It links the actions to the region, the individual to a wider social structure.

α: Locale

resources (including food and bodies) of which social performance consists. It is therefore key to regard materials associated with gatherings as “an extension of the social actor, a gesture […, that] is synonymous with material action”. (Gamble 1998, 438) Material resources can be utilized within the disembodied information transfer (Gamble 1999, 71) The locales where relationship negotiation occurs through appropriate means (bodily resources or additional externalized resources, whatever the appropriate network-level involved is) are indicative of performance either by competent members or skilled practitioners. (Gamble 1998, 438; Gamble 1999, 75)

Social occasions involve a context by which performance is established by disembodied objects.3 Instead of bringing the objects as resources for interaction,

the objects are already part of being-in-the-world and thus more unconsciously influence performance. Lastly, a place is a kind of locale for social occasions that is ‘invested with meanings and associations’. A place might be a human-built or natural environment in which certain (or most) elements are ‘controlled’ by people. For example, a cave is a set of affordances that provide humans and other animals with shelter. Its structure (including opportunities and constrains on size, aspect, head height, floor surface, etc.) will structure behaviour. (Gamble 1999, 75) Another example of a place Gamble mentions are the limestone cliffs at Les Éyzies in the Dordogne, where under the overhangs all kinds of activities are said to have occurred:

3 Gamble names as an example the distinction between a room and the things within the room:

These were places with associations based upon rhythms of encounters, seasons, hunting, growing-up, sleeping and eating around hearths and under rock debris. (…) They produced forms of doing and adapting which recurred and persisted through repeated gatherings and social occasions over many millennia. (Gamble 1998, 439)

Therefore, what is of key importance for the concept of locale is that what is usually associated with archaeological sites should be approached with the perspective that many, if not all activities were social. Residues were among other things, social tools and played a part in social performance. Social life and attention were performed in these locales (Gamble 1999, 76). Moreover, since gatherings and social occasions are persistently present in the archaeological record, and their existence can be primarily regarded as a social consequence (meaning it involved people binding and bonding together) network analysis can provide insight into the mechanisms leading to such a persistence (Gamble 1999, 76). In chapter 2.4 we will discuss which (technological) aspects of lithics relate to this approach and can be made feasible for an interpretative model.

β: Region

landscape of habit can vary between a radius of 40 up to 100 km in scale, and an individual’s exploration range is unlikely to exceed more than 300 kilometres; everything within the radius is considered local activity. (Gamble 1999, 88-89). Raw material transfers are therefore seen as embedded in social activity. It represents the rhythms that resulted in paths and tracks, constructed by individuals routinizing their social life.

Extending the scale of the landscape of habit results in the social landscape. The social landscape is the means by which distanciation, the stretching of social relations beyond the present and the here and now, is achieved through symbolic resources. The social landscape is the ‘spatial outcome of individuals developing their extended network and the appearance of the global network’. (Gamble 1998, 441) The basic assumption here is a negative one: without symbolic means to augment co-presence, there would have been considerable difficulties in maintaining social life at scales through bonds based merely on affective and effective means (Gamble 1999, 144). Positively expressed: in the social landscape the personal network is redefined, as there is an alternation in the resources used during interaction and negotiation (Gamble 1998, 441). A social landscape encompasses a number of intersecting landscapes of habits in which individuals participate in global networks. (Gamble 1999, 91) What is important in the social landscape for Gamble is that if it can be proven to exist, it proves the existence of the release from proximity. The ‘older’ categorizations of personal networks as discussed in ch.2.2 and their affiliated resource-types and their intensities (see table 2.1) find their spatial realization in the region.

Material items are embedded in the broader social systems in such a social landscape. The use of objects encompasses the rhythmic gestures, not only as achieved by collecting materials and manufacturing items, but also by the act of exchange. Gamble points out that the emergence of social landscape precedes the fixation of collective symbolic representation (e.g. through language), and allows individuals to use their individual agency to renegotiate and change the social systems they inherited.

networks are explored and interaction becomes a fixed possibility, regardless of whether it actually occurs or not. These societies consist of ‘distant relatives’ and ‘comparative strangers’. (Gamble 1996, 260) Its spatial scale has no upper limit but differs throughout time and locations. (Gamble 1996, 261; Gamble 1999, 94) It is characterized by a shift from social life being complex to becoming complicated as discussed in chapter 2.1. The complication of life (as illustrated in fig.2.1) introduced the simpler means to deal with social life: by using symbols and material resources social problems could be separated into a series of simple, customary tasks. (Gamble 1998, 443; Gamble 1999, 92) However, Gamble notes that it is unnecessary to discuss the knowledge of places and the use of space in terms of cognition or linguistics, and should rather be regarded as complex behaviour shared with other animals. (Gamble 1996, 263-4) In subchapter 2.5 I will briefly return to this point in discussing the use of cognition for studying RfP. In the social landscape, the release from proximity transformed the components of the personal networks by the symbolic resources: “it is the externalization of creative rhythms that marks out social evolution in the Palaeolithic.” (Leroi-Gourhan 1993 in Gamble 1998, 443) In the next chapter, we will try to establish what the technological correlates in the lithic assemblage that is characteristic for this ‘externalization of creative rhythms’.

γ: Rhythms

Three types of rhythms are of importance here: 1) raw material acquisition, 2) the technology and tool production covered by the chaîne opératoire and 3) skills involved in creating the environment surrounding the hominid, in other words, the taskscape. We will focus on these three a bit closer. Raw material acquisition and transfer illustrate the so-called paths and tracks. The notion of paths and tracks criticises that the usual way of site catchment analysis is not focused on the primarily nomadic induced lifestyle. In this regard, the more ‘traditional’ approach of site catchment analysis necessarily stressed the central functions of sites, which had the result of making the pattern of land use seem lake that of agriculturists with its optimising approach to continuous parcels of land. Mutual environments are not surface-area territories, but rather paths between locales. Leroi-Gourhan (1993, 327) foreshadowed this notion: "The nomad hunter-gatherer visualised the surface of a territory by crossing it; the settled farmer constructed the world in concentric circles around a granary". What has to be emphasized is that for computer models of tracks, is the importance of the social context for sharing knowledge about itineraries constructed by individual hominines. The rise of so-called specific skills, in contradistinction to generic skills, are historically developed at particular places in distinctive contexts. According to Gamble, Middle-Palaeolithic blades are an example of this.

Technology and tool production is meaningful as a rhythm, if it the making of an artefact is not seen as the manifestation of the representation of an idea, but rather regarded as a social skill. Knapping then becomes negotiated through gestures. In this view, tool production is as much a social as a technological performance

After having establishes the outlines and content of the framework used by Gamble, we will now turn to the question: what data has to be used according to this framework in order to make viable hypotheses?

2.4. Spatial and Technological correlates

In this subchapter, an attempt will be made to reconstruct Gamble’s approach towards identifying and describing data that can be used to reconstruct the landscape of habit and by extension, the social landscape. The limiting factor in this attempt is that Gamble does not systematically address the kind of data that is useful for researching the release from proximity, but rather focuses on explaining away why in the three time periods he addresses (500ka-300ka, 300ka-60ka, 60ka-21ka), only the latter has clear evidence for RfP, with reference to a bulk of data and concepts. For this reason, it must be stated that it will be not possible to cover the entirety of Gamble’s approach towards data. It is however clear that Gamble focuses mostly on scale, distance and temporality in the archaeological record. (Gamble 1999, 363) We will focus on spatial data, as well as on technological correlates, to answer the question of what data we have to look for when pointing out the release from proximity. In chapter 3, this account of data correlation will be reintegrated with the larger theoretical framework as set out in subchapter 2.3, and an attempt will be made to make a model for testing hypotheses. What seems to be most important in terms of data is to be able to account for mobility - particularly as accentuated by raw material transfer networks and the density of such network -, and interregional variability in human creativity.

material transfer, as well as in the quantity of material that was transferred. (Gamble 1999, 353) He further establishes that, as a rule, if the temporality of social action is low, the material from further away will nonetheless be transferred into a locale as a retouched tool, rather than as a lump of raw material or as a pre-core. Locales in which raw materials transferred from less than 20km are present can be expected to hold different stages of the chaîne opératoire – as evidenced by refitting, from early stages of the production (e.g. core preparation) to the modifications of tools. (Gamble 1999, 353) Moreover, provisioning of locales, i.e. stocking them with caches of material carries big social implications as ‘places for future action are created’, and could, therefore, form another proxy for enhanced mobility and the habituality carrying and storing stones. Movement from locales would be transformed from gathering to gathering into moving from social occasion to social occasion. (Gamble 1999, 356) More concretely, social occasions hold artefacts that have disembodied gestures. For example, bodies, clay figurines, plant food and dwellings are a focus for social life and performances in which people did not have to be present to participate in and influence human action. Performances related to such artefacts could be setting up a home as including a ritualistic attaching to a place and its memories, “playing around the fire”, by which Gamble means the phenomenological impressions pyrotechnics could induce on children and adults engaging around a hearth, or the rituals surrounding burials, shortly “saying goodbye to the dead”.4 (Gamble 1999,

400-13)

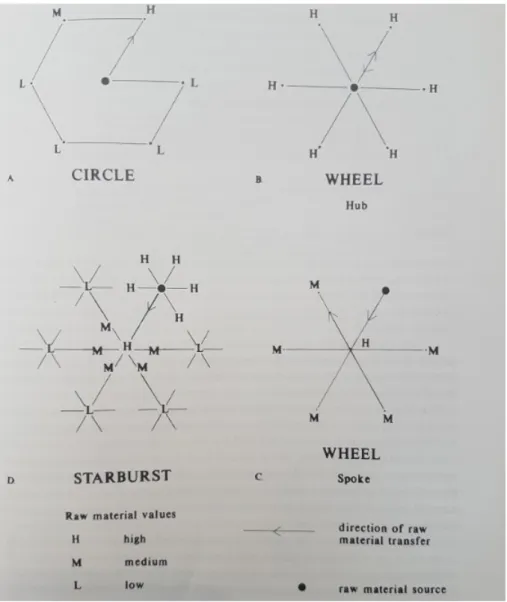

Secondly, Gamble states that locales holding large samples of raw material from different sources allow us to infer different things with regard to the routinization of raw material acquisition and transport. Gamble gives a scenario in which many raw materials from many different sources are present at a locale, most of which are derived from sources closer to the locale. In a star-shaped

4 I have to stress here that I do not necessarily agree with Gamble that these performances can be

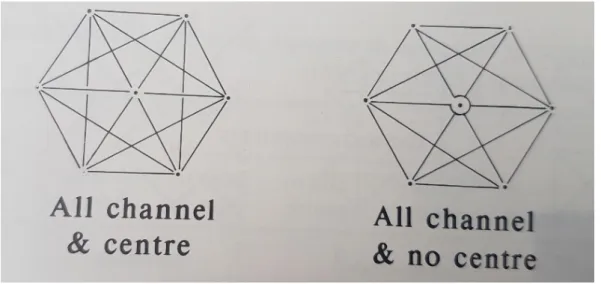

Figure 2.5: All-channel network patterns (Gamble 1999, 45)

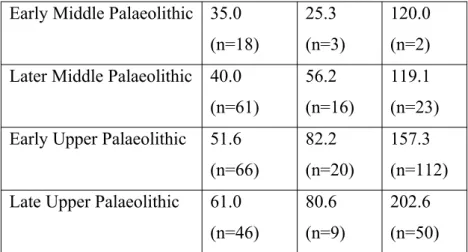

If a certain limit can be established to the distance of raw material transfer, the nodes in the wheel network can be set accordingly, which in the case of a 20km limit, should be some 5-10km in length: “otherwise there should be a greater incidence of raw materials from further afield in each of the locales”. (Gamble 1999, 359) In contrast, Gamble concludes, Upper Palaeolithic transfers were organized differently, based upon the increased distances as well as the differences between the locales in terms of transfer as shown in the archaeological record (see table 2.3). Moreover, the number of technological modes other than blanks and tools which are transferred beyond 20km increases markedly. The modes in question have been categorized according to qualitative and quantitative standards in eight modes (see table 2.4). Most importantly here, is that as parts of the chaîne opératoire, and sometimes the entire chaîne opératoire are moved to remarkably further distances, it becomes evident that the environment increasingly poses a less limiting factor on raw material transportation. (Gamble 1999, 361)

Table 2.3: A comparison between three regions of the average maximum distance in each locale/level over which lithic material has been transferred. N = the number of locales/levels in each region (after Gamble 1999, 314)

Region SW (km) NW

(km)

NC (km)

Lower Palaeolithic 32.7 (n=25)

Early Middle Palaeolithic 35.0 (n=18)

25.3 (n=3)

120.0 (n=2) Later Middle Palaeolithic 40.0

(n=61)

56.2 (n=16)

119.1 (n=23) Early Upper Palaeolithic 51.6

(n=66)

82.2 (n=20)

157.3 (n=112) Late Upper Palaeolithic 61.0

(n=46)

80.6 (n=9)

202.6 (n=50)

Table 2.4: The eight modes of lithic exploitation. (Gamble 1999, 243)

one thing, but coarser grained materials, leading to raw material acquisition for a vast array of basing building blocks implies a different kind of social complexity, not necessarily a less developed one. For example, a tool technology such as Auchelean doesn’t require high-quality raw material. Traveling larger distances, therefore, was not a necessary requirement. This endangers the variable of raw material acquisition, not so much in assessing increased regional mobility (people travelling larger distances to gain raw materials), but insofar high regional mobility in itself is a requirement for assessing a social landscape. If different tools are not in need of higher quality materials but have a greater variance in the raw materials per functional category, it is not implied that there is a less developed social complexity.5

Further, a circular high density, all-channel network is characteristic of movement patterns during the EUP, although it varies per region. In such networks, there is a directed pattern of transfers, which are either provisioning places or focusing on particular individuals in an exchange system (Gamble 1999, 360)

However, what makes a social landscape is the intersection of landscapes of habit, resulting in the extension of individual agency across time and space and in the creation of a global network. (Gamble 1999, 363) Increased inter-regional variability in human creativity is the consequential hallmark of the social landscape. In such a social landscape, society would be complicated rather than complex, which as shown in previous chapters, means that information becomes available through symbols and signs. (Gamble 1999, 363-4) In these societies, extended and global networks for the first time become a possibility. Whereas artefacts in a complex society could be extensions of the body, they could represent or personify a person or the existence of an extended network in absentia. “When associated with social occasions […] they formed a substitute for co-presence that can be understood because they belonged to a complicated, sequenced set of routines.” (Gamble 1999, 365) Moreover, chains of connections forged over longer distances seem are accompanied by a greater diversification of items in the archaeological record. (Gamble 1999, 366)

In Gamble’s own assessment, the release from proximity as evidenced by the social landscape comes into existence in the Upper Palaeolithic. His approach

seeks to justify the long-held divisions in the data between this and earlier periods. (Gamble 1999, 363) Fortunately, Gamble himself devised a table with which important Palaeolithic terms find correspondence with Gamble’s own ideas as showcased by table 2.5.

Table 2.5: The use and correspondence of terms in Palaeolithic archaeology. (Gamble 1999, 367)

To clarify, I will quote Gamble’s own description of the terms involved:

“Assemblage – a collection of artifacts from a specific segment of an archaeological site.

Industry – a distinctive complex or configuration of artefact types and type frequencies that recurs among two or more assemblages

Tradition – a group of industries whose artifactual similarities are sufficient that they belong to some broader culture-historical block of technological ideas and practices

Culture – a polythetic set of specific and comprehensive artefact types which consistently recur together in assemblages within a limited geographic area

Due to the scope of this thesis, I will not make an excessive criticism on the categorization of tradition and culture, as the base distinction between the Middle Palaeolithic and Upper Palaeolithic. Rather, it is clear from the assessment that the release from proximity occurs in perhaps the technocomplex and clearly, in the social landscape – given the type of networks that is typical for them, namely the extended and global respectively. The difficulty lies in attempting to quantify what a tradition or culture is, or how we can see the technocomplex or, indeed, the social landscape in the archaeological record. He analyses the occurrence of various Mousterian assemblages as a dominant element in the twenty-two districts in the region of France. Of these assemblages, MTA is the most widespread (nineteen districts and parts of England and Belgium), but it is nonetheless a ‘wildly inaccurate’ estimate that it would encompass an inter-regional distribution of c. 800,000 km2 over a minimum lifespan of 20Kyr, and would mask a range of

processes (including migration) that could account for that spread. (Gamble 1999, 368) The spread of the proto-Aurignacian, can be shown by isochrons plotted on a map (see Gamble 1999, fig.7.4) It bears this regionalization clearly, because its movement (zonal [east-west] instead of meridional [north-south]) is rapid in contrast to Late Mousterian and transitional technocomplexes.6 (Gamble 1999,

371-4) Rapid spread of assemblages over regions, therefore, imply enhanced social capabilities.

To summarize, the data that is most important for studying the release from proximity is most notably the data that proves the existence of the social landscape. In this sense, scale, distance and temporality are of key importance. Before turning to the hypothetical framework with which the release from proximity can be studied, some principal theoretical criticisms will be raised against viewing the release from proximity as a (set of) cognitive trait(s).

2.5 A critical footnote: the cognitive implications of RfP

6 But see Gamble’s own nuancing of the dating methods involved. (Gamble 1999, 374) Rapid

At this point, it is beyond mere convenience to discuss the relation between RfP as a social/behavioural phenomenon and its cognitive demands. Especially insofar RfP implicates human social modernity, it becomes of interest what kind of cognitive capacities must have evolved to make this possible, or alternatively, which rudimentary capacities did evolve to cognitive abilities (perhaps brought about through cultural evolution) that made RfP possible. At first sight, there might exist a tendency to reason prior to examining empirical data, to assume humans who expressed RfP were capable, cognitively speaking, to consciously separate themselves from others and store their knowledge of particular relationships in a long-term memory (perhaps working memory). Such a social cognitive skill might have coincided with a broader cognitive capacity to consciously anticipate events beyond the readily observable world, some of which involved social relationships.7

In this subchapter, I aim to shed some light on this relationship. Gamble himself, I will argue, has not only made a shift in his literature from the phenomenon to the capacity but has increased the explanatory burden in doing so. The relevance of this discussion for the current thesis should be clear: it concerns the question what the best way of studying RfP is, namely insofar it is a phenomenon that can be seen a posteriori or a capacity that can be recognized a priori to archaeological data, specifically lithic data. I will end the discussion on the note that both approaches could mutually enhance one another.

In “the Palaeolithic society and the release from proximity”, it is not the case that Gamble simply does not want to go into the cognitive details of RfP. When stressing the methodological differences between a social theorist approach and a primatologist approach towards studying society, Gamble notes that this distinction often involves two differentiated anthropological views of culture: the cognitivist and the phenomenological approach. The cognitivist approach (which arguably is not the same as giving cognitive details for some phenomenon or behaviour) is in his view the wrong strategy as it is “an exercise in classification involving mental representations of social structures where the stability of culture is achieved through linguistic transmission”. (Gamble 1998, 429) Rather, he contends that a phenomenological approach should be taken, precisely because

7 See Wynn an Coolidge (2009) for the argumentative structure of cognitive assessments in

the phenomenon of the rhythms and gestures of the body during performance of social life is a non-linguistic manifestation of social memory. Admittedly, although it is true that with regard to the differences in anthropological views Gamble is more inclined to favour the phenomenological view (e.g. see Gamble 1999, 33-4).

But doesn’t such a social memory and the entire phenomenon of repeated rhythms not rely on some underlying cognitive mechanism? Of course, Gamble does not deny that this is the case, but the phenomenological approach stresses the importance of focusing on what material culture has to offer qua social information. By stating that language is not the prime symbolic achiever of RfP, a hard-to-assess mental trait is avoided in the formula of complicated sociality. What it exactly means epistemologically for RfP to be a phenomenon, is that it can be assessed a posteriori. This does not mean that e.g. social phenomena are readily available to be distilled from artefacts; rather their production can be viewed as the consequence of social and cultural performance. (Gamble 1998, 493) Subchapters 2.2 and 2.3 underline this. Networks have to be assessed not as mere potentials, but as actuals. And the actual of the extended network is achieved in the social landscape. The important aspect of the rhythms refers to that repetition of normalized social behaviour, not in pontentia, but as actual.

However, insofar there are cognitive implications, they are problematic at best when they are directly related to the theory of RfP (e.g. see footnote 2). In more recent years, RfP has been embedded in the Social Brain Hypothesis (SBH) by Gowlett, Dunbar and Gamble (e.g. 2011, 202). Essentially, it focuses on the cognitive and social underpinnings of sociality. In this analysis, community seize is an emergent property of the social complexity, dispersed social systems in which some members are only encountered infrequently, which is extra demanding (Gamble et al. 2011, 116). The cognitive aspects that are required for advanced social cognitive competencies include (mainly) a theory of mind and higher-order intentionality (mentalizing and mind-reading skills).8 Raising the

8 I want to shortly touch upon a concern that I have for assuming that there is such a thing as the

question for cognition is important for our understanding of sociality in human evolution:

To what extent, for example, is the ability to detach oneself from the immediacies of the physical world ( a requirement for the basic level theory of mind or second-order intentionality – minimally needed to operate effectively in a human social world) necessary to be able to visualize the end product of a tool in the raw material of a core? Indeed, this capacity to detach oneself from the immediacy of the world is, in all probability, necessary to construct tools designed to facilitate the extraction of resources sensu extractive foraging (Gamble et al. 2014, 117)

The question of cognition provides the basis for understanding how RfP was a possibility. Therein lies much of value for researchers trying to investigate the SBH. However, Insofar RfP is researched qua phenomenon, the existence of underlying cognitive mechanisms are already implicated. Since my aim here is to reframe recognition of RfP within a lithic-based research schema, we do not have to concern ourselves with its cognitive aspect.

To conclude, while it is interesting to speculate on the cognitive capacities for the release from proximity, it is not a necessary component for assessing its existence. That is precisely because RfP is a phenomenon rather than a capacity. In fact, as soon as Gamble himself focuses on cognitive indicators for modernity, it is not at all clear anymore where the release from proximity comes in on the human timeline. However, studying the archaeological record for cues indicating enhanced social behaviour should ideally complement cognitive studies. If both are able, independently from each other, to indicate a heavy social change, both as

capacity and as cultural phenomenon somewhere on the hominin timeline, it would highlight its mutual complementary value. This claim can however can only be speculatively approached in this thesis, as I will briefly do in chapter 3.

3. The release from proximity as a hypothetical model

3.1 Ordering and simplifying technological correlates of RfP

In this subchapter, a reiteration will be made of the spatial and technological data necessary to study the release from proximity as set out in subchapter 2.4. As stated before, the most important data relates to scale, distance and temporality. The release from proximity is primarily found in the social landscape. Locales are expected to reflect this externalization: if they are social occasions rather than gatherings, locales transform to places and thus resemble this externalization.

With regard to scale, determining what the difference is between region and local should be of key importance. Region sizes can either be simply determined by geographical or ecological delineations. As an example, Gamble has devised such a regional model for Europe (fig.31 [66]). Naturally, climate influenced demographics and thereby the dissemination of artefacts. Insofar it can be accounted for, fluctuations in population or cultural movements should be contrasted with possible co-occurring climate fluctuations. Demographic reconstruction is valuable, but demographic size does not necessarily indicate concrete patterning of social behaviour among groups.9 Determining if and how

demographic patterning varied across a continent, or even within a region, allows

9 See French (2015, 164 [table 1]) for an overview and critical discussion of archaeological proxies

us to account for varying network sizes. Network-based models of interaction, therefore, should be implemented when reconstructing possible modes of social interaction. Types of transfer networks alone do not necessarily point out whether an assemblage can be associated with the release from proximity. The Châtelperronian is described by Gamble as well suited to the wheel-shaped Neanderthal networks with high mobility, short residential stay and limited carrying of materials. (Gamble 1999, 382)

Networks are best modelled on the distances of raw material transfer between source and locale. To account for this transfer via the archaeological record, source studies have to be done. In addition, refitting of tools and the production sequence is valuable for pointing out the presence of different modes of technology present at a locale. The more Most importantly in reconstructing raw material transfer is determining the sources of raw materials, as well as tools. This might be limited by contingent lithic sources unknown today; for example, flint sources along the river might have transported raw material for acquisition further down the riverbank. (beter engels) However, A bunch of accumulated stones at a locale, although possibly indicative of high-valued use in a lower or higher density network, and in effect of the routinization of behaviour related to raw material transfer, does not imply release from proximity. Provisioning could be an indicator of the release from proximity since it involves storing information on storing stones (or other items) that are beyond the bodily proximity of an individual or group of individuals in absentia. Moreover, long stratified sequences in caves highlight material for a changing narrative of assemblages and techniques. Regionalization can be accounted for by the sequenced difference of distances from sources, as well as the modes of technology associated with the sources. (Gamble 1999, 371)

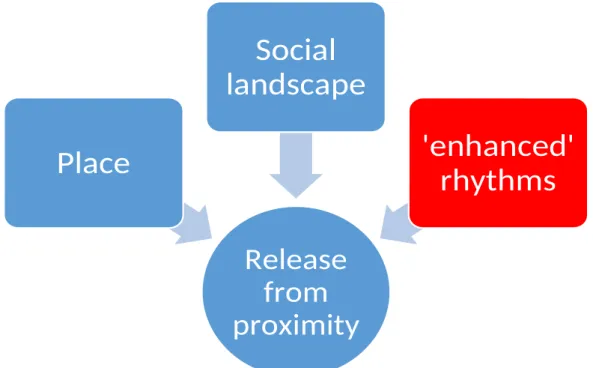

3.2 An extended and simplified model of RfP in the lithic assemblage

Devising a model with which hypotheses with regard to RfP is hard, since it is not possible to simply list a set of conditions that have to be fulfilled for it to be likely. I think however, that it is possible to make a hierarchy of the concepts and ideas explored thus far, and subsequently, relate them to the associated data. I will attempt to explain what segments of the hierarchy account for what kind of hypotheses. A further restriction will be that I only focus on three phenomena per category to reduce further complications. The three categories are representations of the locale, region and rhythm; respectively the place, the social landscape and ‘enhanced rhythms’. Each of these categories carries three associated phenomena as spokes around a hub (see fig. 3.1, p.40). The used colours on the spokes are indicative of the likelihood by which they express the associated hub: orange represents a concept that can be easily accounted for by data, but is in itself not sufficient to represent the hub-concept. Purple represents a concept that is harder accounted for by data, for example, because it is unclear what exactly would constitute an activity, or ambiguity in the data is more likely to occur, but is in itself sufficiently indicative of the hub-concept. Green represents a concept that has associated easily identifiable data and is very likely indicative of the hub-concept. Hubs are either blue or red. A blue hub indicates that there is a reasonable likelihood that if data underpinning the node-concepts is sufficient, the hub-concept can be assessed for its (non-)existence within a particular assemblage. Red, on the other hand, means that the hub-concept is unlikely to be accounted for by the archaeological data. Every hub has three nodes connected by spokes, making one system. The nodes represent conditions for activation of the hub. Only data underpinning a node-concept ‘activates’ it. It cannot be readily assumed as an existent condition on its own. Some data can account (partly) for multiple node-concepts across systems and are therefore rather understood dynamically than secluded. All nodes with a different colour than green are sufficiently indicative of the hub if they are ‘activated’ in conjunction with a different node. However, purple nodes can be sufficient nodes on their own if sufficient data is provided, as explained below.

memories and associations beyond its immediate presence for individuals. In this regard, establishing whether one is dealing with a social occasion rather than a place, which is a social occasion ‘festered with meanings’, is not important for further interpretation. Both are established through subconcepts that are indicative of RfP. More or less obviously, if a locale holds full-blown symbolic artefacts (regardless whether they are lithic-made or of exotic material), or dwelling structures, it is very likely to be a place. Since it has been established that symbolic communication was the modus operandi in a global network, regardless of which specific segment of the network it was associated with in everyday life it is an evident marker of RfP. Provisioning is another, although less obvious characteristic of a place. Storing items is a social practice associated with the extension of information beyond the direct environment; the knowledge of stored items must be carried with an individual or group of individuals when traveling. Showing provision as an activity in the archaeological record in itself might be somewhat unclear, but a simple accumulation of concentrated material at one place on a locale will generally not represent such activity. Ideally, clear structuring of item-placement in or along the setting of a locale should be sought after. Lastly, refitting and research on sources of chaîne opératoires present in locales might reveal that raw material transfer did not hold a fall-off curve for distant travelling, if complete or partially parts of the production sequence can be found far from the source. To make more quantifiable, what far means, I have set a distance for more than 100 km, as a distance between source and locale. As indicated earlier, increased distance of raw material transfer is not necessarily indicative of the extension of social engagement. I would argue however, that a consistent patterning of widely distributed chaîne opératoires crossing the threshold distance between locales dated at around the same period ultimately does show that distance matters, because it would show agreement in shared information (that material can be carried further) among groups vastly disconnected.

highlight human creativity in their intersection. In a conceptual setting, it would mean that some shared type of object X is represented in both assemblages A and B within a shared region. Whether it is indicative of trade or shared culture is not important in this regard. As far as the lithic assemblages are concerned, it would most ideally include finding key artefacts X of assemblage A mixed with other key artefacts Y in assemblage B in a clearly defined, unambiguous layer, or sequence of layers. What is hard, however, is showing that this practice of sharing items occurred regularly enough to indicate that landscapes of habit did, in fact, socially interact. Reconstructing material transfer networks, as far as data is concerned, is somewhat akin to the point raised with regard to the further movement of (partially) complete chaîne opératoires from their sources. However, this involves analyzing on a semi-regional or regional scale the intensities with which certain locales were used. Consistent preference for locales and sources further located from each other with the former being reused multiplying in the region, gives rise to structuring the movement of material transfer networks. However, these are not in themselves sufficiently indicative of a social landscape if it turns out they are characterized as low-density networks. Regional high density all-channel networks form the ideal for indicating the social landscape, but this would either require proving that trade occurred, or alternatively that many landscapes of habits shared a culture. The latter approach would in that regard be an extension of studying two or more landscapes of habit as describe above. Lastly, rapid cultural spread in a large region is characterized mainly by what we are interested in here, involving large scale, great lengths of distance over little time. Ideally, comparative analyses should be made of changes in movement between the arrival of new assemblages and the ‘natural’ spread of older assemblages.

learning it by gestures, but involves using the discursive consciousness. Reflection and metareflection upon actions become a mode of thought and consequently influence the way gestures associated with for example dancing, learning, rituals are structured more or less consciously, diversifying and categorizing different modes of gestures. The routinization of future action means that anticipation can be negotiated beyond the bodily co-presence of others. A red encirclement of your sister’s birthday on a calendar would be an example of a complicated, semiotically induced anticipation without someone else negotiating this anticipation in bodily co-presence. Lastly, a symbolically charged taskscape is a more accentuated form of the diversification of social gestures. In the ‘normal’ taskscape specific skills are socially transferred. A symbolically charged taskscape structures these specific skills along symbolic understanding such that the skills themselves become categories and therefore objects of social negotiation. To put it bluntly, in a symbolically charged landscape, taste for skills and behaviour itself becomes an object of negotiation. Thus, preference as a clear (i.e. no longer unconsciously expressed) category of desire enters the social epistemology, and thus social discourse. Admittedly the account of enhanced rhythms as set out here is highly speculative and I see little to no use for the lithic record to be bothered attempting to prove any of the elements set out here. Why bother with it in the first place then? I would argue that it is here where the cognitivist framework could prove itself more than useful. I will not attempt here to integrate the cognitivist approach exhaustively, and I want to keep it purely speculative, but it could complement any research done on the ‘rhythmic’ aspect of Gamble’s framework extensively. Although in chapter 2.5 I focused mostly on the differences between the ‘phenomenological’ approach employed by Gamble in studying the Release from proximity as contrasted to the cognitivist approach, I also suggested that both approaches could be mutually beneficial for the same cause. Here, I think, such an opportunity puts itself to the fore.

4. Conclusion

Release

from

proximity

Place

Social

landscape

'enhanced'

rhythms

In this thesis, I have attempted to answer the question How can we make a model with which the release from proximity can be shown to be reflected in the evolution of lithic technology in the European Palaeolithic? Answering this question proved somewhat more difficult than I anticipated and I am doubtful about its successfulness. First, it was made clear that in order to study Palaeolithic society from a bottom-up approach, human agency and creativity had to be at the nexus of social performance. The release from proximity is that emergent social phenomenon in which individuals socially act beyond direct face-to-face interaction. In addition, RfP makes society complicated rather than complex and the concomitant transformation of social actions addressing more than one factors at a time, to the possibility to divide and make successions of simple operations. Second, such complication can be accounted for by personal network structures and is resembled mostly by the extended and global networks. In other words, symbolism as a resource of communication was an emergent property of extending networks. Third, the Palaeolithic framework was reconstructed. It featured a broad outline of locales, rhythms and regions describing the intenseness, routinization and scale of social performance on different levels each of which could be corroborated with different segments of the personal network. The fourth part existed of picking up those elements that were most likely indicative of RfP. I described the kinds of data in subchapter 2.4 and ordered them in subchapter 3.1. Most important for the lithic assemblage is data relating to scale, distance and temporality. Fifth, as an important intermezzo, I briefly addressed the question of whether or not Gamble’s social approach implies cognitive features that should be researched and argued that this was not the case. However, I suggested that if an approach studies human sociality in earlier humans through cognition, findings from the RfP-model could be beneficial to its interpretation and vice versa. Finally, in constructing the model I proposed a system of hierarchy that specifically indicates what kind of phenomena are related to what concept and how, if at all it can be sufficiently accounted for by archaeological data.

Abstract

This thesis focuses on the release from proximity (RfP) as it was originally proposed by Clive Gamble and will attempt to establish a model with which sociality in prehistoric societies can be studied. RfP is a social phenomenon that displays an individual’s capability to carry social life with him or her beyond direct face-to-face interaction. This opens up the possibility to create extended and global networks with other individuals, and importantly, the possibility to maintain, and invest in, social relationships with individuals with whom there is no interaction on a daily basis. As such, RfP indicates a particular human trait. Insofar it is possible to reconstruct the release from proximity through lithic materiality, specifically with respect to its evolution throughout the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, I will attempt to construct a model to point out RfP in this evolutionary trajectory.

With regards to the theory underpinning the release from proximity, I will 1a) examine Gamble’s earlier and later accounts of the importance of network theory and 1b) revise the older accounts wherever it is deemed necessary, 2) sketch the broader theoretical framework for a bottom-up approach of assessing Palaeolithic societies, 3) point out the lithic indicators that are relevant for studying the release from proximity, specifically focusing on those that can be used to determine the (non-)existence of the social landscape, social occasions/places and ‘enhanced’ rhythms, criticize 4a) the underlying cognitive assumptions about RfP that are implied in earlier literature and explicitly noted in Gamble’s later works, and 4b) examine its relation to other cognitive capabilities.

List of References

Abramiuk, M.A., 2012. The Foundations of Cognitive Archaeology. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press.

Corbey, R., 2000. On Becoming Human: Mauss, the Gift and Social Origins, in A. Vandevelde (ed.), Gifts and interests. Leuven: Peeters, 157-74.

Dunbar, R. I. M., 2009. The Social Brain Hypothesis and Its Implications for Social Evolution. Annals of Human Biology 36 (5), 562–72.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460902960289

French, J.C., 2016. Demography and the Palaeolithic Archaeological Record. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 23 (1), 150–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-014-9237-4

Gamble, C., 1993. Timewalkers: The Prehistory of Global Colonization. Stroud: Alan Sutton.

Gamble, C., 1996. Making Tracks, in J. Steele and S. Shennan (eds), The

Archaeology of Human Ancestry: Power, Sex and Tradition. New York

(NY): Routledge, 253–75.

Gamble, C., 1998. Palaeolithic Society and the Release from Proximity: A Network Approach to Intimate Relations. World Archaeology 29 (3), 426– 49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1998.9980389

Gamble, C., 1999. The Palaeolithic Societies of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gamble, C., 2007. Origins and Revolutions: Human Identity in Earliest

Prehistory. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press.

Gamble, C., J. Gowlett, and R.I.M. Dunbar, 2011. The Social Brain and the Shape of the Palaeolithic. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 21 (1), 115–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774311000072

Gamble, C., J. Gowlett, and R.I.M. Dunbar, 2014. Thinking Big: How the Evolution of Social Life Shaped the Human Mind. London: Thames & Hudson.

Ingold, T., 1993. The Temporality of the Landscape. World Archaeology 25 (2), 152-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1993.9980235

Leroi-Gourhan, A., 1993. Gesture and Speech. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press. Lewis-Williams, D. and D. Pearce, 2005. Inside the Neolithic Mind. London:

Thames & Hudson.

Mithen, S., 1996. The Prehistory of the Mind: A Search for the Origins of Art, Religion and Science. London: Thames & Hudson.

Quiatt, D. and V. Reynolds, 1993. Primate Behaviour: Information, Social Knowledge and the Evolution of Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, S.G.B., 2010. Constraints on Social Networks, in R.I.M. Dunbar, C. Gamble and J.A.J. Gowlett (eds), Social Brain and Distributed Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 115-34.

Rodseth, L., R.W. Wrangham, A. Harringan and B.B. Smuts, 1991. The Human Community as a Primate Society. Current Anthropology 32 (3), 221–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/203952

Sleutels, J., 2013. The Flintstones Fallacy. Dialogue and Universalism 1, 1-11. Strum, S. S. and B. Latour, 1987. Redefining the Social Link: From Baboons to

Humans. Social Science Information 26 (4), 783–802. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901887026004004

Suddendorf, T., 2013. The Gap: The Science of What Separates Us from Other

Animals. New York (NY): Basic Books.

Wezenbeek, M., 2018. Fallacious minds: Locating the Flintstones Fallacy within the Archaeological Literature of Cognition. Leiden (unpublished BA thesis University of Leiden).

Wynn, T. and F. L. Coolidge, 2009. Implications of a Strict Standard for Recognizing Modern Cognition, in S. Beaune, F. L. Coolidge, and T. Wynn (eds), Cognitive archaeology and Human Evolution, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 117-27.

Zhou, W.-X., D. Sornette, R.A. Hill, and R.I.M. Dunbar, 2005. Discrete Hierarchical Organization of Social Group Sizes. Proceedings of the Royal

Society of London 272 (1561), 439–44.